Establishment of Haredi High-School Yeshivas in Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yeshivat Derech Chaim Kiryat Gat American Friends of Sderot Amutat Lapid the Max & Ruth Schwartz Hesder Institutions Mission Statement

ech Chaim er K i D r t y a a v t i G h s a e t Y The Friedberg Community Initiative Program The Yedidut-Toronto Foundation Yeshivat Derech Chaim Kiryat Gat American Friends of Sderot Amutat Lapid The Max & Ruth Schwartz Hesder Institutions Mission Statement Giving back to the community is no burden on our students – it is the direct, inescapable consequence of their studies here. It is not in vain that our Yeshiva is called "Derech Chaim" – the "Path of Life". We make every effort to make it clear to our students that the Torah that they study here is not theoretical – it is geared is to lead and direct them to take those same high ideals and put them into practice in their daily lives - in their hobbies, careers and life-choices. The Rashbi Study Partners Program Twice a week, Kiryat Gat Hesder students go to study Talmud and Parshat Shavua with young students at the nearby "Rashbi" Mamlachti Dati elementary school. Due to its proximity our students can now engage in this activity twice a week and the young children are in turn encouraged to visit the Yeshiva as well. In general, these children come from very economically and religiously challenged backgrounds. Having a "big brother" from the local Hesder Yeshiva is invaluable in building their respect for Torah and connecting them to proper role models. Community Rabbinate Program Amit L’Mishpacha A number of our Rabbis also serve as the beloved The Family Associate Program spiritual leaders of different local congregations. In this context, they are busy giving talks and lectures as well as helping families in their community in various ways. -

Israel's National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

Leap of Faith: Israel’s National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict Middle East Report N°147 | 21 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iv I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Religious Zionism: From Ascendance to Fragmentation ................................................ 5 A. 1973: A Turning Point ................................................................................................ 5 B. 1980s and 1990s: Polarisation ................................................................................... 7 C. The Gaza Disengagement and its Aftermath ............................................................. 11 III. Settling the Land .............................................................................................................. 14 A. Bargaining with the State: The Kookists ................................................................... 15 B. Defying the State: The Hilltop Youth ........................................................................ 17 IV. From the Hills to the State .............................................................................................. -

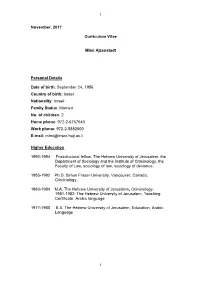

CV July 2017

1 November, 2017 Curriculum Vitae Mimi Ajzenstadt Personal Details Date of birth: September 24, 1956 Country of birth: Israel Nationality: Israeli Family Status: Married No. of children: 2 Home phone: 972-2-6767540 Work phone: 972-2-5882600 E-mail: [email protected] Higher Education 1992-1994 Post-doctoral fellow, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Department of Sociology and the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law, sociology of law, sociology of deviance. 1985-1992 Ph.D. Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada, Criminology. 1980-1984 M.A. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Criminology. 1981-1982: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Teaching Certificate, Arabic language 1977-1980 B.A. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Education, Arabic Language 1 2 Appointments at the Hebrew University 2012- present Full Professor, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 2007– 2012 Associate Professor, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 2002- 2007 Senior Lecturer, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 1994-2002 Lecturer, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work. Service in other Academic Institutions Summer, 2011 Visiting Professor, Cambridge University. Summer, 2010 Visiting Professor. University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. 2005 -2006 Visiting Professor. University of Maryland, Maryland, USA. Winter, 2000 Visiting Scholar. Stockholm University, Sweden. Fall 1999 Visiting Scholar. Yale University, New-Haven, Connecticut, U.S.A., Law School. -

Rambam Hilchot Talmud Torah

Rambam Hilchot Talmud Torah Rabbi Yitzchak Etshalom Part 7 7: If the *minhag hamedina* (local custom) was to pay the teacher, he brings him his payment. [the father] is obligated to pay for his education until he learns the entire Written Torah. In a place where the custom is to teach the Written Torah for money, it is permissible to teach for a salary. However, it is forbidden to teach the Oral Law for a salary, as it says: *R'eh limadti etchem hukkim umishpatim ka'asher tzivani hashem* (See, I have taught you laws and judgements just as Hashem commanded me) (Devarim [Deuteronomy]4:5) just as I [Moshe] studied for free, so you learned from me for free. Similarly, when you teach in the future, teach for free, just as you learned from me. If he doesn't find anyone to teach him for free, he should find someone to teach him for pay, as it says: *Emet k'ne* (acquire - or buy - truth) (Mishlei [Proverbs] 23:23) I might think that [in that case] he should teach others for money, therefore Scripture says: *v'al timkor* (and do not sell it) ) )ibid.); so you see that it is forbidden to teach for pay, even if his teacher taught him for pay. Q1: Why the distinction between the written law and the oral law? KB: We've always been allowed to pay scribes, eh? YE: Another response: someone who is teaching the pure text is merely a facilitator - teaching grammar, lexicon, history etc. Therefore, he is not in the model of Moshe Rabbenu, from whom the entire halakha of free teaching is derived. -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

The Beit Shemesh Running Club

The Beit Shemesh Running Club Marathoners Unite Religiously Diverse Israeli City By Hillel Kuttler pon completing each Monday’s 90-min- Strous could also have been referring to the ath- ute group run at 10:30 p.m., Rael Strous letic group to which he belongs, the Beit Shemesh Utakes leave of his mates and drives to a Running Club. The club unites disparate Jewish nearby bakery whose fresh-from-the-oven whole segments of society around a common appetite wheat rolls he craves. for pavement and trails, then sends them and Dripping 10 miles’ worth of street-pounding their differences home until the next workout. sweat and still clad in running shorts, Strous tends Its members and town officials view the run- to draw gazes and conversational interest from the ning club as a stark example of sports’ power to black-hatted, black-coated ultra-Orthodox men foster tolerance and inclusion. That is no small Members of the Beit who likewise visit the bakery for a late nibble here feat, especially following a series of ugly incidents Shemesh Running Club, in Beit Shemesh, an unassuming city of 85,000, in late 2011 near a Beit Shemesh elementary Shlomo Hammer and his 20 miles west of Jerusalem. The curiosity seekers school that had just opened on property that father Naftali Hammer inquire about Strous’ workout; he asks what Jewish adjoins—but also divides—the separate neigh- (front right and front scholarly texts they’ve been studying. borhoods where Modern Orthodox and ultra- left), stretching before “It’s just a bunch of guys getting together, Orthodox Jews live. -

SCHOLARSHIP OPPORTUNITIES at TAU the International MA

SCHOLARSHIP OPPORTUNITIES AT TAU The International MA Program in Ancient Israel Studies: Archaeology and History of the Land of the Bible at Tel Aviv University is pleased to announce three scholarship opportunities for the academic year 2015-2016. 1. $13,000 US AYALIM TUITION ASSISTANCE SCHOLARSHIP A number of $13,000 US tuition assistance scholarships are offered to students who meet the following requirements: * Applicant's age must range from 21 to 30. * Applicant must be recognized by Masa Israel Journey (according to Masa's criteria for scholarships). 2. $2,500/ 5,000 US TUITION ASSISTANCE SCHOLARSHIPS $2,500/ 5,000 USD tuition assistance scholarships will be granted to a number of students with proven records of academic excellence who wish to broaden their knowledge and understanding of Ancient Israel. Scholarships for the academic year of 2015-2016 will be granted by the academic committee of the Department of Archaeology and Near Eastern Cultures based on the following: * Academic CV * Final transcript from last academic establishment * Abstract of the final paper submitted to the last academic establishment 3. FULL TUITION SCHOLARSHIPS FOR STUDENTS FROM CHINA Full tuition scholarships will be awarded based on academic excellence, and will allow students from China to study the archaeology and history of the Land of the Bible - IN the land of the Bible, at one of the most prestigious programs currently available in the field of Ancient Israel Studies. A number of accepted students will also be awarded free dormitories and living expense grants, in addition to full tuition scholarships. Admission requirements for students from China: * Academic achievements: Students must have a GPA of 3 or above, or an average score of 80% from their BA degree. -

Burden Sharing and the Haredim

8 Burden Sharing and the Haredim On March 12, 2014 the Knesset passed, on its which scholars should remain exempt, but also third reading, Amendment 19 to the Military states that draft evaders will be subject to arrest if Service Law, which aims to widen the participation quotas are unmet. !e comprehensive exemption of Ultra-Orthodox young men and yeshiva granting all Haredi yeshiva students aged 22 students in military and civilian national service. and over who join the workforce is of particular !is amendment also aims to promote their significance. integration into the working population. On April 17, 2014, the Ministerial Committee on Background: !e History of Burden Sharing in Military Service set concrete steps for the amendment’s implementation the Exemption (!e Arrangement and follow up. !ese were given the force of a for Deferral of Army Service Cabinet resolution. Under the new arrangement, by Yeshiva Students) the amendment will take full e"ect on July 1, Compulsory military service applies under the 2017, following an adjustment period. When in Security Service Law (Combined Version) of 1986. full force, the military or civilian national service According to this law, Israeli citizens are subject inductees will number 5,200 a year (two thirds to conscription at age 18 unless granted an of the age cohort according to current figures). exemption. Exemption was the subject of lively Until then, yeshiva students will be able to defer debates between yeshiva heads and the political their enlistment and receive an exemption at age leadership in the early days of the state. !e 22, as long as the yeshivot meet their recruitment executive committee of the Center for Service targets, which will be implemented according to to the People considered the conscription of the mandated schedule: in 2014, a total of 3,800 yeshiva students, and in March 1948 authorized Haredim are expected to join the IDF or national a temporary army service deferment for yeshiva service; in 2015, 4,500; and 5,200 in the years that students whose occupation was Torah study.1 follow. -

THRESHING FLOORS AS SACRED SPACES in the HEBREW BIBLE by Jaime L. Waters a Dissertation Submitted to the Johns Hopkins Universit

THRESHING FLOORS AS SACRED SPACES IN THE HEBREW BIBLE by Jaime L. Waters A dissertation submitted to The Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland August 2013 © 2013 Jaime L. Waters All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Vital to an agrarian community’s survival, threshing floors are agricultural spaces where crops are threshed and winnowed. As an agrarian society, ancient Israel used threshing floors to perform these necessary activities of food processing, but the Hebrew Bible includes very few references to these actions happening on threshing floors. Instead, several cultic activities including mourning rites, divination rituals, cultic processions, and sacrifices occur on these agricultural spaces. Moreover, the Solomonic temple was built on a threshing floor. Though seemingly ordinary agricultural spaces, the Hebrew Bible situates a variety of extraordinary cultic activities on these locations. In examining references to threshing floors in the Hebrew Bible, this dissertation will show that these agricultural spaces are also sacred spaces connected to Yahweh. Three chapters will explore different aspects of this connection. Divine control of threshing floors will be demonstrated as Yahweh exhibits power to curse, bless, and save threshing floors from foreign attacks. Accessibility and divine manifestation of Yahweh will be demonstrated in passages that narrate cultic activities on threshing floors. Cultic laws will reveal the links between threshing floors, divine offerings and blessings. One chapter will also address the sociological features of threshing floors with particular attention given to the social actors involved in cultic activities and temple construction. By studying references to threshing floors as a collection, a research project that has not been done previously, the close relationship between threshing floors and the divine will be visible, and a more nuanced understanding of these spaces will be achieved. -

Women-Join-Talmud-Ce

OBSERVANCE Women Join Talmud Celebration As the daf yomi cycle of Talmud learning concludes this week, a Jerusalem study group breaks a barrier By Beth Kissileff | July 30, 2012 7:00 AM | Comments: 0 (Margarita Korol) This week, hundreds of thousands of people are expected to gather in various venues around the world for what’s being billed as “the largest celebration of Jewish learning in over 2,000 years.” The biggest American event, in New Jersey’s MetLife Stadium on Aug. 1, is expected to fill most of the arena’s 90,000 seats. The occasion is the siyum hashas, the conclusion of a cycle of Talmud study first proposed by Meir Shapiro, rabbi of Lublin, at the First World Congress of World Agudath Israel—an umbrella organization A Different Voice representing ultra-Orthodox Jewry—in Vienna in 1923. When a woman learns the art of Torah Shapiro’s idea was that Jews around the world could chanting, she realizes she is part of a build unity by studying the same page of Talmud at the new religious tradition—as well as a very same time. If a Jew learns one page per day, known as old, sacred one daf yomi, it will take almost seven and a half years to By Sian Gibby complete all 2,711 pages of the Babylonian Talmud. This week’s siyum hashas marks the conclusion of the 12th cycle of daf yomi study since 1923. Historically, one group of Jews has often been limited in access to this text: women. The ultra-Orthodox world does not, for the most part, approve of women studying Talmud; as one rabbi representative of this view, or hashkafa, explains, such scholarship is “not congruent with the woman’s role” in Judaism. -

Rocument RESUME ED 045 767 UD 011 084 Education in Israel3

rOCUMENT RESUME ED 045 767 UD 011 084 TITLE Education in Israel3 Report of the Select Subcommittee on Education... Ninety-First Congress, Second Session. INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, E.C. House Ccmmittee on Education and Labcr. PUB DATE Aug 70 NOTE 237p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MP-$1.00 BC-$11.95 DESCRIPTORS Acculturation, Educational Needs, Educational Opportunities, *Educational Problems, *Educational Programs, Educational Resources, Ethnic Groups, *Ethnic Relations, Ncn Western Civilization, Research and Development Centers, *Research Projects IDENTIFIERS Committee On Education And Labor, Hebrew University, *Israel, Tel Aviv University ABSTRACT This Congressional Subcommittee report on education in Israel begins with a brief narrative of impressions on preschool programs, kibbutz, vocational programs, and compensatory programs. Although the members of the subcommittee do not want to make definitive judgments on the applicability of education in Israel to American needs, they are most favorably impressed by the great emphasis which the Israelis place on early childhood programs, vocational/technical education, and residential youth villages. The people of Israel are considered profoundly dedicated to the support of education at every level. The country works toward expansion of opportunities for education, based upon a belief that the educational system is the key to the resolution of major social problems. In the second part of the report, the detailed itinerary of the subcommittee is described with annotated comments about the places and persons visited. In the last part, appendixes describing in great depth characteristics of the Israeli education system (higher education in Israel, education and culture, and the kibbutz) are reprinted. (JW) [COMMITTEE PRINT] OF n. -

Israel and the Middle East News Update

Israel and the Middle East News Update Wednesday, April 17 Headlines: • PA Prime Minister: Trump’s Peace Deal Will Be ‘Born Dead’ • Amb. Dermer: Trump Peace Plan Should Give Jews Confidence • Final Election Results: Likud 35, Blue White 35 • Netanyahu Celebrates Victory: I Am Not Afraid of the Media • Nagel: “Currently, there is No Solution to Gaza” • In First, US Publishes Official Map with Golan Heights as Part of Israel • Israel Interrogates US Jewish Activist at Airport Commentary: • Channel 13: “The Main Hurdle: Lieberman Versus the Haredim” − By Raviv Drucker, Israeli journalist and political commentator for Channel 13 News • Ha’aretz: “How the Israeli Left Can Regain Power - Stop Hating the Haredim” − By Benjamin Goldschmidt, a rabbi in New York City. He studied in the Ponevezh (Bnei Brak), Hebron (Jerusalem) and Lakewood (New Jersey) Yeshivas S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace 633 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, 5th Floor, Washington, DC 20004 The Hon. Robert Wexler, President ● Yoni Komorov, Editor ● Aaron Zucker, Associate Editor News Excerpts April 17, 2019 Jerusalem Post PA Prime Minister: Trump’s Peace Deal Will Be ‘Born Dead’ Newly sworn in Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh said Tuesday night that US President Donald Trump’s peace plan will be “born dead." Shtayyeh said the American “Deal of the Century,” was declaring a “financial war” on the Palestinian people, during an interview with The Associated Press. "There are no partners in Palestine for Trump. There are no Arab partners for Trump and there are no European partners for Trump," Shtayyeh said in the interview. See also, “PALESTINIANS TURN TO RUSSIA TO BYPASS US PEACE PLAN” (Jerusalem Post) Jerusalem Post Amb.