Jewish Studies in the Nordic Countries Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

י Three Steps to Father's House

בס“ד Parshat Bo 8 Shevat, 5777/February 4, 2017 Vol. 8 Num. 22 This issue of Toronto Torah is dedicated by Rochel and Jeffrey Silver נ“י in honour of the birth of their granddaughter Faigy Rivka Three Steps to Father’s House Rabbi Mordechai Torczyner Over a two-week period our ancestors To Father’s House works on several Seen in this light, the Exodus requires were told how to prepare for our levels, one of which is a parable for our that we be identified as the rightful national Exodus. Those commands, departure from Egypt. As the Talmud heirs of Avraham and Sarah, to merit recorded in our parshah, described (Sotah 11a) describes, our labour in that return home. This is the role of three activities: Egypt was perpetual and unrewarding, the three preparatory activities outlined Designation and sacrifice of the and we shared the protagonist’s sense in our parshah: korban pesach (Shemot 12:1-6); of not belonging. Suffering made us long Circumcision was Avraham’s mitzvah, Placement of blood from the korban for the house of our Father, and we left and it became the mark of the Jew. pesach on the entrances of their in haste. (Shemot 12:11) We displayed Korbanot were a hallmark of Avraham homes (12:7, 21-23); great ambivalence, though, en route to and Sarah, who built altars each time Circumcision of all males (12:43-50). our land; we even claimed that we had they settled a new part of Canaan. been better off in Egypt. The end of the Placement of blood from the korban We could view these three activities as book of Yehoshua (24:2-4) is part of the pesach marks the structure as a elements of the korban pesach. -

THE APOCALYPTIC WAR AGAINST GOG of MAGOG. MARTIN BUBER VERSUS MEIR KAHANE Por: Rico Sneller

EL CONFLICTO PALESTINO-ISRAELI: SOLUCIONES Y DERIVAS Profesor David Noel Ramírez Padilla Rector del Tecnológico de Monterrey Lic. Héctor Núñez de Cáceres Rector de la Zona Occidente Ing. Salvador Coutiño Audiffred Dr. Ricardo Romero Gerbaud Director General del Campus Querétaro Dirección Dr. Ricardo Romero Gerbaud Mtro. José Manuel Velázquez Hurtado Director de Profesional y Graduados en María José Juárez Becerra Administración y Ciencias Sociales Edición Mtra. Angélica Camacho Aranda Natalia Fernández, Alicia Hernández, Rodrigo Directora del Departamento de Relaciones Pesce Internacionales y Formación Humanística Asistentes de Edición Mtro. Kacper Przyborowski Director de la Licenciatura en Relaciones Internacionales Dr. Tomás Pérez Vejo Dra. Marisol Reyes Soto Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia INAH University of Queens, Ireland Dra. Avital Bloch Dr. Tamir Bar-On Universidad de Colima Tecnológico de Monterrey Dra. Marie-Joelle Zahar Université de Montréal Dra. Claudia Barona Castañeda Universidad de Las Américas Puebla Dr. Thomas Wolfe University of Minnesota, Twin-Cities Dr. Janusz Mucha AGH, Cracovia GRUPO FORUM Retos Internacionales, ISSN: 2007-8390. Año 5, No. 11, Agosto-Diciembre 2014, publicación semestral. Editada por el Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, Campus Querétaro, a través de la División de Administración y Ciencias Sociales, bajo la dirección del Departamento deRelaciones Internacionales y Humanidades, domicilio Av. Eugenio Garza Sada No. 2501, Col. Tecnológico, C.P. 64849, Monterrey, N.L. Editor responsable: Dr. Ricardo Romero Gerbaud. Datos de contacto: [email protected], http://retosinternacionales.com, teléfono y fax: 52 (442) 238 32 34. Impresa por FORUM arte y comunicación S.A. de C.V., domicilio Av. del 57, número 12, Colonia Centro, C.P. -

Zionism - a Successor to Rabbinical Judaism?

Zionism - A Successor to Rabbinical Judaism? By Gol Kalev Outline I) Introduction II) Historical Background -Judaism to Zionism -Zionism as a Successor to Rabbinical Judaism? Why It Has Not Happened So Far: -Israel-Related Hurdles -America-Related Hurdles III) Transformation of Judaism: Why Now Might Be a Ripe Time: -Changing Circumstances in Israel -New Threats (Post-Zionism) -Enablers of Jewish Transformation -Changing Circumstances in America -New Threats (End of Jewish Glues, Israel-Bashing, Dispersal of Jewish Capital) -Enablers of Jewish Transformation IV) Judaism 3.0 2 INTRODUCTION “Palestine for the Jews!” That was the headline of The London Times on November 9, 1917, the week after the British government issued the Balfour Declaration. A mere 30 years later, the headline turned into reality with the establishment of the State of Israel, homeland of the Jewish People. The return of the Jews to their ancestral homeland has driven Rabbinical Judaism, the form of Judaism practiced for the last 1900 years, to a unique challenge. After all, Rabbinical Judaism’s formation coincided with the Jews’ exit to the Diaspora, and to a large extent was developed to accommodate the state of exile. Much of its core is based on the yearning for the return to Israel. The propensity of its rituals, prayers and customs are centered on the Land of Israel, from having synagogues face Jerusalem to reciting a prayer for return three times a day. A question arose: Now that the Jews are allowed to return to the Land of Israel, how will Judaism evolve? During the 20th century, the Jewish people re-domiciled and concentrated in two core centers: Israel and the United States. -

Understanding the Major Branches of Modern Judaism May 10, 2012

Understanding the Major Branches of Modern Judaism May 10, 2012 Initial terms: 24 or 72 kinds Torah/Talmud (oral/written law).Halacha orthopraxy/orthodoxy, haskalah Babylonian Talmud kabbalah, Sephardic, Ashkenazi (with material gleaned from Wikipedia articles- no access to my books yet) Modern Judaism is loosely broken into three main branches: Orthodox Judaism is the approach to Judaism which adheres to the traditional interpretation and application of the laws and ethics of the Torah as legislated in the Talmudic texts by the Sanhedrin ("Oral Torah") and subsequently developed and applied by the later authorities known as the Gaonim, Rishonim, and Acharonim. Orthodox Jews are also called "observant Jews"; Orthodoxy is known also as "Torah Judaism" or "traditional Judaism". Orthodox Judaism generally refers to Modern Orthodox Judaism and Haredi Judaism (Chasidic Chabad) but can actually include a wide range of beliefs. Orthodoxy collectively considers itself the only true heir to the Jewish tradition. The Orthodox Jewish movements generally consider all non-Orthodox Jewish movements to be unacceptable deviations from authentic Judaism; both because of other denominations' doubt concerning the verbal revelation of Written and Oral Torah, and because of their rejection of Halakhic precedent as binding. As such, Orthodox groups characterize non-Orthodox forms of Judaism as heretical Reform Judaism is a phrase that refers to various beliefs, practices and organizations associated with the Reform Jewish movement in North America, the United Kingdom and elsewhere.[1] In general, Reform Judaism maintains that Judaism and Jewish traditions should be modernized and compatible with participation in the surrounding culture. Many branches of Reform Judaism hold that Jewish law should be interpreted as a set of general guidelines rather than as a list of restrictions whose literal observance is required of all Jews.[2][3] Similar movements that are also occasionally called "Reform" include the Israeli Progressive Movement and its worldwide counterpart. -

M E O R O T a Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (Formerly Edah Journal)

M e o r o t A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly Edah Journal) Tishrei 5770 Special Edition on Modern Orthodox Education CONTENTS Editor’s Introduction to Special Tishrei 5770 Edition Nathaniel Helfgot SYMPOSIUM On Modern Orthodox Day School Education Scot A. Berman, Todd Berman, Shlomo (Myles) Brody, Yitzchak Etshalom,Yoel Finkelman, David Flatto Zvi Grumet, Naftali Harcsztark, Rivka Kahan, Miriam Reisler, Jeremy Savitsky ARTICLES What Should a Yeshiva High School Graduate Know, Value and Be Able to Do? Moshe Sokolow Responses by Jack Bieler, Yaakov Blau, Erica Brown, Aaron Frank, Mark Gottlieb The Economics of Jewish Education The Tuition Hole: How We Dug It and How to Begin Digging Out of It Allen Friedman The Economic Crisis and Jewish Education Saul Zucker Striving for Cognitive Excellence Jack Nahmod To Teach Tsni’ut with Tsni’ut Meorot 7:2 Tishrei 5770 Tamar Biala A Publication of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah REVIEW ESSAY Rabbinical School © 2009 Life Values and Intimacy Education: Health Education for the Jewish School, Yocheved Debow and Anna Woloski-Wruble, eds. Jeffrey Kobrin STATEMENT OF PURPOSE Meorot: A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly The Edah Journal) Statement of Purpose Meorot is a forum for discussion of Orthodox Judaism’s engagement with modernity, published by Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School. It is the conviction of Meorot that this discourse is vital to nurturing the spiritual and religious experiences of Modern Orthodox Jews. Committed to the norms of halakhah and Torah, Meorot is dedicated -

Israel's National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

Leap of Faith: Israel’s National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict Middle East Report N°147 | 21 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iv I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Religious Zionism: From Ascendance to Fragmentation ................................................ 5 A. 1973: A Turning Point ................................................................................................ 5 B. 1980s and 1990s: Polarisation ................................................................................... 7 C. The Gaza Disengagement and its Aftermath ............................................................. 11 III. Settling the Land .............................................................................................................. 14 A. Bargaining with the State: The Kookists ................................................................... 15 B. Defying the State: The Hilltop Youth ........................................................................ 17 IV. From the Hills to the State .............................................................................................. -

CV July 2017

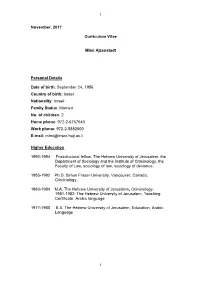

1 November, 2017 Curriculum Vitae Mimi Ajzenstadt Personal Details Date of birth: September 24, 1956 Country of birth: Israel Nationality: Israeli Family Status: Married No. of children: 2 Home phone: 972-2-6767540 Work phone: 972-2-5882600 E-mail: [email protected] Higher Education 1992-1994 Post-doctoral fellow, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Department of Sociology and the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law, sociology of law, sociology of deviance. 1985-1992 Ph.D. Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada, Criminology. 1980-1984 M.A. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Criminology. 1981-1982: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Teaching Certificate, Arabic language 1977-1980 B.A. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Education, Arabic Language 1 2 Appointments at the Hebrew University 2012- present Full Professor, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 2007– 2012 Associate Professor, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 2002- 2007 Senior Lecturer, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 1994-2002 Lecturer, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work. Service in other Academic Institutions Summer, 2011 Visiting Professor, Cambridge University. Summer, 2010 Visiting Professor. University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. 2005 -2006 Visiting Professor. University of Maryland, Maryland, USA. Winter, 2000 Visiting Scholar. Stockholm University, Sweden. Fall 1999 Visiting Scholar. Yale University, New-Haven, Connecticut, U.S.A., Law School. -

Finnish University Intelligentsia and Its German Idealism Tradition

1 INTELLECTUALS AND THE STATE: FINNISH UNIVERSITY INTELLIGENTSIA AND ITS GERMAN IDEALISM TRADITION Jukka Kortti, Adjunct Professor (Docent) University of Helsinki, Department of Political and Economic Studies, Section of Social Science History [email protected] Article (Accepted version) Post-print (ie final draft post-refereeing) Original citation: JUKKA KORTTI (2014). INTELLECTUALS AND THE STATE: THE FINNISH UNIVERSITY INTELLIGENTSIA AND THE GERMAN IDEALIST TRADITION Modern Intellectual History, 11, pp 359-384 doi:10.1017/S1479244314000055 2 Abstract INTELLECTUALS AND THE STATE: FINNISH UNIVERSITY INTELLIGENTSIA AND ITS GERMAN IDEALISM TRADITION The article examines the making of the Finnish intelligentsia and its relation to the state and the nation. The problem is analysed primarily from the perspective of student activism in the twentieth century. The development is viewed in the context of nationalism, (cultural) modernism, and radicalism in the development of the public sphere. The main source consists of the research findings of the student magazine Ylioppilaslehti (Student Magazine), which is not just “any student paper,” but a Finnish institution that has seen most of Finland’s cultural and political elite pass through its editorial staff in the twentieth century. The article demonstrates the importance of German idealism, as theorised by the Finnish statesman and philosopher J.W. Snellman, and its vital role in the activities of the Finnish university intelligentsia well into the 21st century. 3 INTELLECTUALS AND THE STATE: FINNISH UNIVERSITY INTELLIGENTSIA AND ITS GERMAN IDEALISM TRADITION INTRODUCTION In 2013, there has been quite a fuss around Finnish philosopher Pekka Himanen in the Finnish public sphere. Himanen is internationally known as the researcher of the information age – together with Spanish sociologist Manuel Castells, for instance. -

Rav Yisroel Abuchatzeira, Baba Sali Zt”L

Issue (# 14) A Tzaddik, or righteous person makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. (Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach; Sefer Bereishis 7:1) Parshas Bo Kedushas Ha'Levi'im THE TEFILLIN OF THE MASTER OF THE WORLD You shall say it is a pesach offering to Hashem, who passed over the houses of the children of Israel... (Shemos 12:27) The holy Berditchever asks the following question in Kedushas Levi: Why is it that we call the yom tov that the Torah designated as “Chag HaMatzos,” the Festival of Unleavened Bread, by the name Pesach? Where does the Torah indicate that we might call this yom tov by the name Pesach? Any time the Torah mentions this yom tov, it is called “Chag HaMatzos.” He answered by explaining that it is written elsewhere, “Ani l’dodi v’dodi li — I am my Beloved’s and my Beloved is mine” (Shir HaShirim 6:3). This teaches that we relate the praises of HaKadosh Baruch Hu, and He in turn praises us. So, too, we don tefillin, which contain the praises of HaKadosh Baruch Hu, and HaKadosh Baruch Hu dons His “tefillin,” in which the praise of Klal Yisrael is written. This will help us understand what is written in the Tanna D’Vei Eliyahu [regarding the praises of Klal Yisrael]. The Midrash there says, “It is a mitzvah to speak the praises of Yisrael, and Hashem Yisbarach gets great nachas and pleasure from this praise.” It seems to me, says the Kedushas Levi, that for this reason it says that it is forbidden to break one’s concentration on one’s tefillin while wearing them, that it is a mitzvah for a man to continuously be occupied with the mitzvah of tefillin. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13864-3 — the Israeli Settler Movement Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler , Cas Mudde Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13864-3 — The Israeli Settler Movement Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler , Cas Mudde Index More Information Index 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the, 2 Ariel, Uri, 76, 116 1949 Armistice Agreements, the, 2 Arutz Sheva, 120–121, 154, 205 1956 Sinai campaign, the, 60 Ashkenazi, 42, 64, 200 1979 peace agreement, the, 57 Association for Retired People, 23 Australia, 138 Abrams, Eliott, 59 Aviner, Shlomo, 65, 115, 212 Academic Council for National, the. See Professors for a Strong Israel B’Sheva, 120 action B’Tselem, 36, 122 connective, 26 Barak, Ehud, 50–51, 95, 98, 147, 235 extreme, 16 Bar-Ilan University, 50, 187 radical, 16 Bar-Siman-Tov, Yaacov, 194, 216 tactical, 34 Bat Ayin Underground, the, 159 activism BDS. See Boycott, Divestment and moderate, 15–16 Sanctions transnational, 30–31 Begin, Manahem, 47, 48, 118–119, Adelson, Sheldon, 179, 190 157, 172 Airbnb, 136 Beit El, 105 Al Aqsa Mosque, the, 146 Beit HaArava, 45 Al-Aqsa Intifada. See the Second Intifada Beitar Illit, 67, 70, 99 Alfei Menashe, 100 Beitar Ironi Ariel, 170 Allon, Yigal, 45–46 Belafonte, Harry, 14 Alon Shvut, 88, 190 Ben Ari, Michael, 184 Aloni, Shulamit, 182 Bendaña, Alejandro, 24 Altshuler, Amos, 189 Ben-Gurion, David, 46 Amana, 76–77, 89, 113, 148, 153–154, 201 Ben-Gvir, Itamar, 184 American Friends of Ariel, 179–180 Benn, Menachem, 164 American Studies Association, 136 Bennett, Naftali, 76, 116, 140, 148, Amnesty International, 24 153, 190 Amona, 79, 83, 153, 157, 162, 250, Benvenisti, Meron, 1 251 Ben-Zimra, Gadi, 205 Amrousi, Emily, 67, 84 Ben-Zion, -

The Audacity of Holiness Orthodox Jewish Women’S Theater עַ זּוּת שֶׁ Israelבִּ קְ Inדוּשָׁ ה

ׁׁ ְִֶַָּּּהבשות שעזּ Reina Rutlinger-Reiner The Audacity of Holiness Orthodox Jewish Women’s Theater ַעזּּו ֶׁת ש in Israelִּבְקּדו ָׁשה Translated by Jeffrey M. Green Cover photography: Avigail Reiner Book design: Bethany Wolfe Published with the support of: Dr. Phyllis Hammer The Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA Talpiot Academic College, Holon, Israel 2014 Contents Introduction 7 Chapter One: The Uniqueness of the Phenomenon 12 The Complexity of Orthodox Jewish Society in Israel 16 Chapter Two: General Survey of the Theater Groups 21 Theater among ultra-Orthodox Women 22 Born-again1 Actresses and Directors in Ultra-Orthodox Society 26 Theater Groups of National-Religious Women 31 The Settlements: The Forge of Orthodox Women’s Theater 38 Orthodox Women’s Theater Groups in the Cities 73 Orthodox Men’s Theater 79 Summary: “Is there such a thing as Orthodox women’s theater?” 80 Chapter Three: “The Right Hand Draws in, the Left Hand Pushes Away”: The Involvement of Rabbis in the Theater 84 Is Innovation Desirable According to the Torah? 84 Judaism and the Theater–a Fertile Stage in the Culture War 87 The Goal: Creation of a Theater “of Our Own” 88 Differences of Opinion 91 Asking the Rabbi: The Women’s Demand for Rabbinical Involvement 94 “Engaged Theater” or “Emasculated Theater”? 96 Developments in the Relations Between the Rabbis and the Artists 98 1 I use this term, which is laden with Christian connotations, with some trepidation. Here it refers to a large and varied group of people who were not brought up as Orthodox Jews but adopted Orthodoxy, often with great intensity, later in life. -

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor.