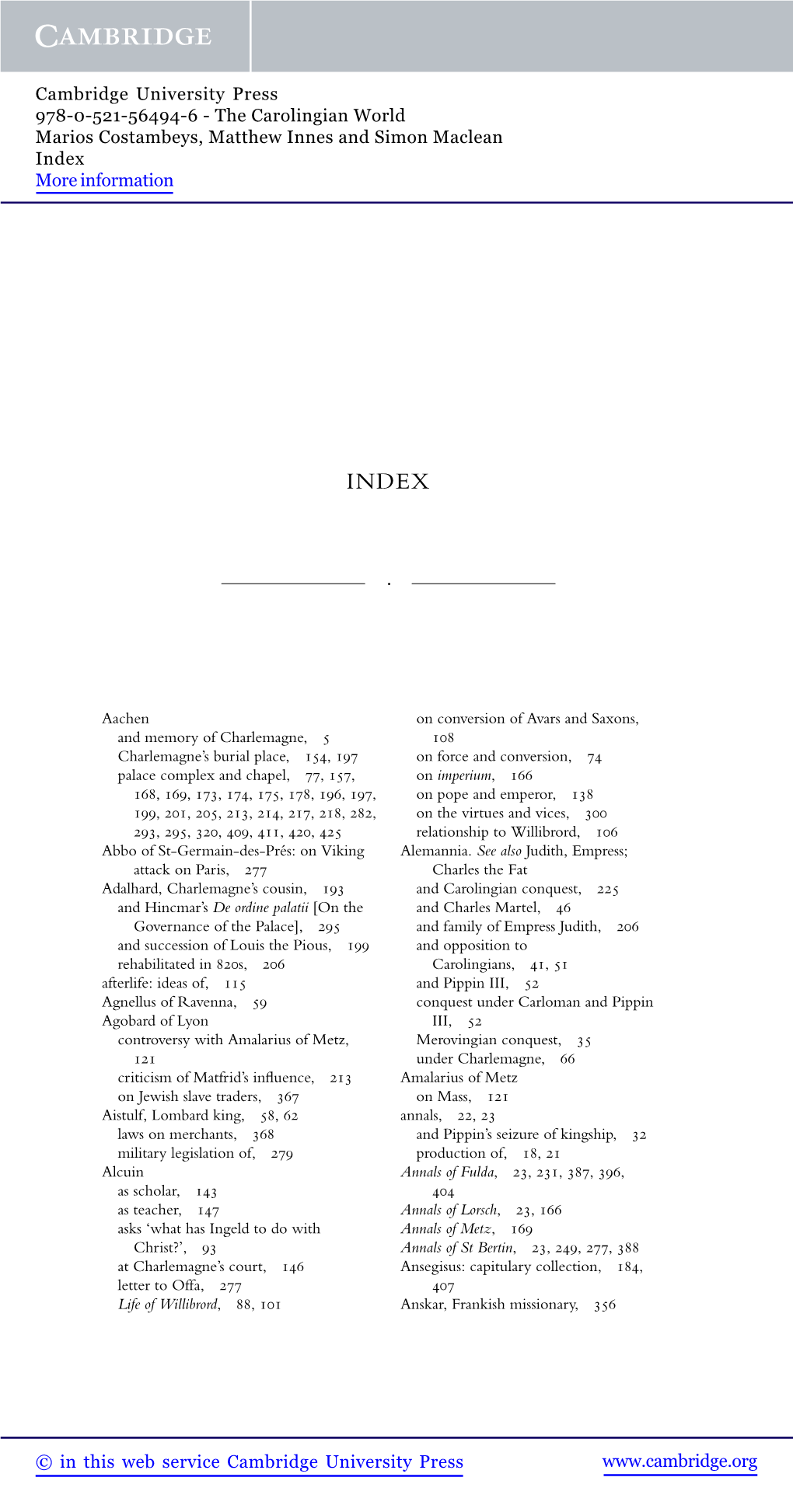

9780521564946 Index.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LECTURE 5 the Origins of Feudalism

OUTLINE — LECTURE 5 The Origins of Feudalism A Brief Sketch of Political History from Clovis (d. 511) to Henry IV (d. 1106) 632 death of Mohammed The map above shows to the growth of the califate to roughly 750. The map above shows Europe and the East Roman Empire from 533 to roughly 600. – 2 – The map above shows the growth of Frankish power from 481 to 814. 486 – 511 Clovis, son of Merovich, king of the Franks 629 – 639 Dagobert, last effective Merovingian king of the Franks 680 – 714 Pepin of Heristal, mayor of the palace 714 – 741 Charles Martel, mayor (732(3), battle of Tours/Poitiers) 714 – 751 - 768 Pepin the Short, mayor then king 768 – 814 Charlemagne, king (emperor, 800 – 814) 814 – 840 Louis the Pious (emperor) – 3 – The map shows the Carolingian empire, the Byzantine empire, and the Califate in 814. – 4 – The map shows the breakup of the Carolingian empire from 843–888. West Middle East 840–77 Charles the Bald 840–55 Lothair, emp. 840–76 Louis the German 855–69 Lothair II – 5 – The map shows the routes of various Germanic invaders from 150 to 1066. Our focus here is on those in dark orange, whom Shepherd calls ‘Northmen: Danes and Normans’, popularly ‘Vikings’. – 6 – The map shows Europe and the Byzantine empire about the year 1000. France Germany 898–922 Charles the Simple 919–36 Henry the Fowler 936–62–73 Otto the Great, kg. emp. 973–83 Otto II 987–96 Hugh Capet 983–1002 Otto III 1002–1024 Henry II 996–1031 Robert II the Pious 1024–39 Conrad II 1031–1060 Henry I 1039–56 Henry III 1060–1108 Philip I 1056–1106 Henry IV – 7 – The map shows Europe and the Mediterranean lands in roughly the year 1097. -

The Heirs of Alcuin: Education and Clerical Advancement in Ninth-Century Carolingian Europe

The Heirs of Alcuin: Education and Clerical Advancement in Ninth-Century Carolingian Europe Darren Elliot Barber Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Institute for Medieval Studies December 2019 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. iii Acknowledgements I wish to thank my supervisors, Julia Barrow and William Flynn, for their sincere encouragement and dedication to this project. Heeding their advice early on made this research even more focused, interesting, and enjoyable than I had hoped it would be. The faculty and staff of the Institute for Medieval Studies and the Brotherton Library have been very supportive, and I am grateful to Melanie Brunner and Jonathan Jarrett for their good advice during my semesters of teaching while writing this thesis. I also wish to thank the Reading Room staff of the British Library at Boston Spa for their friendly and professional service. Finally, I would like to thank Jonathan Jarrett and Charles West for conducting such a gracious viva examination for the thesis, and Professor Stephen Alford for kindly hosting the examination. iv Abstract During the Carolingian renewal, Alcuin of York (c. 740–804) played a major role in promoting education for children who would later join the clergy, and encouraging advanced learning among mature clerics. -

Memorable Crises. Carolingian Historiography and the Making of Pippin's Reign, 750-900 F.C.W. Goosmann

Memorable Crises. Carolingian Historiography and the Making of Pippin’s Reign, 750-900 F.C.W. Goosmann Summary This study explores the way in which Frankish history-writers retroactively dealt with the more contentious elements of the Carolingian past. Changes in the political and moral framework of Frankish society necessitated a flexible interaction with the past, lest the past would lose its function as a moral anchor to present circumstances. Historiography was the principal means with which later generations of Franks were able to reshape their perception of the past. As such, Frankish writers of annals and chronicles presented Pippin the Short (c. 714-768), the first Carolingian to become king of the Franks, not as a usurper to the Frankish throne, but as a New David and a successor to Rome’s imperial legacy. Pippin’s predecessor, the Merovingian king Childeric III (742-751), on the other hand, came to be presented as a weak king, whose poor leadership had invited the Carolingians to take over the kingdom for the general well-being of the Franks. Most of our information for the period that witnessed the decline of Merovingian power and the rise of the Carolingian dynasty derives from Carolingian historiography, for the most part composed during the reigns of Charlemagne (d. 814) and Louis the Pious (d. 840). It dominates our source base so profoundly that, to this day, historians struggle to see beyond these uncompromising Carolingian renderings of the past. In many ways, the history of the rise of the Carolingian dynasty in the eighth century can be viewed as a literary construction of ninth-century design, and the extent to which this history has been manipulated is not at all easy to discern. -

A Neglected Aspect of Carolingian Queenship

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 1 QUEENSHIP, NUNNERIES AND ROYAL WIDOWHOOD IN CAROLINGIAN EUROPE Sometime during the last decade of the ninth century, Archbishop Fulk of Rheims composed a harshly-worded letter of admonition to the former empress Richildis, the second wife of the late Carolingian ruler Charles the Bald (843– 77).1 The archbishop had heard some worrying stories concerning her lifestyle, and felt it incumbent upon him to warn her against the damage she was doing to her chances of eternal life by surrounding herself with associates engaged in „anger, brawling, dissensions, burnings, murders, debauchery, dispossession of the poor and plundering of churches.‟ He urged her instead to show consideration for the health of her soul by living with piety and sobriety, and by performing good works to make up for the fact that virginity, the highest state to which a Christian woman could aspire, was now beyond her.2 We would be wrong to read this letter as representing the views of an impartial onlooker. There was not a black and white principle at stake: Fulk was hardly untarnished by the stain of „brawling‟ and „dissension‟ himself, as shown by his involvement in a particularly murky and violent factional struggle which ultimately led to his assassination.3 Moreover, from what we know about her later life, it is unlikely that Richildis was really behaving as badly as he thought.4 The archbishop of Rheims was one of the most prominent of the churchmen of the Carolingian world who, sponsored by the ruling dynasty, had been engaged since the mid-eighth century in an earnest and ambitious project to reform society according to their interpretation of Christian principles. -

THE DISSEMINATION and RECEPTION of the ORDINES ROMANI in the CAROLINGIAN CHURCH, C.750-900

THE DISSEMINATION AND RECEPTION OF THE ORDINES ROMANI IN THE CAROLINGIAN CHURCH, c.750-900 Arthur Robert Westwell Queens’ College 09/2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2 Arthur Robert Westwell Thesis Summary: The Dissemination and Reception of the Ordines Romani in the Carolingian Church, c.750- 900. The ordines romani are products of a ninth-century attempt to correct liturgy across Europe. Hitherto, scholarship has almost exclusively focused on them as sources for the practices of the city of Rome, narrowly defined, disregarding how they were received creatively and reinterpreted in a set of fascinating manuscripts which do not easily fit into traditional categories. This thesis re- envisages these special texts as valuable testimonies of intent and principle. In the past few decades of scholarship, it has been made very clear that what occurred under the Carolingians in the liturgy did not involve the imposition of the Roman rite from above. What was ‘Roman’ and ‘correct’ was decided by individuals, each in their own case, and they created and edited texts for what they needed. These individuals were part of intensive networks of exchange, and, broadly, they agreed on what they were attempting to accomplish. Nevertheless, depending on their own formation, and the atmosphere of their diocese, the same ritual content could be interpreted in numerous different ways. Ultimately, this thesis aims to demonstrate the usefulness of applying new techniques of assessing liturgical manuscripts, as total witnesses whose texts interpret each other, to the ninth century. Each of the ordo romanus manuscripts of the ninth century preserves a fascinating glimpse into the process of working out what ‘correct’ liturgy looked like, by people intensely invested in that proposition. -

European Middle Ages, 500-1200

European Middle Ages, 500-1200 Previewing Main Ideas EMPIRE BUILDING In western Europe, the Roman Empire had broken into many small kingdoms. During the Middle Ages, Charlemagne and Otto the Great tried to revive the idea of empire. Both allied with the Church. Geography Study the maps. What were the six major kingdoms in western Europe about A.D. 500? POWER AND AUTHORITY Weak rulers and the decline of central authority led to a feudal system in which local lords with large estates assumed power. This led to struggles over power with the Church. Geography Study the time line and the map. The ruler of what kingdom was crowned emperor by Pope Leo III? RELIGIOUS AND ETHICAL SYSTEMS During the Middle Ages, the Church was a unifying force. It shaped people’s beliefs and guided their daily lives. Most Europeans at this time shared a common bond of faith. Geography Find Rome, the seat of the Roman Catholic Church, on the map. In what kingdom was it located after the fall of the Roman Empire in A.D. 476? INTERNET RESOURCES • Interactive Maps Go to classzone.com for: • Interactive Visuals • Research Links • Maps • Interactive Primary Sources • Internet Activities • Test Practice • Primary Sources • Current Events • Chapter Quiz 350 351 What freedoms would you give up for protection? You are living in the countryside of western Europe during the 1100s. Like about 90 percent of the population, you are a peasant working the land. Your family’s hut is located in a small village on your lord’s estate. The lord provides all your basic needs, including housing, food, and protection. -

''Was There a Carolingian Italy?'' Politics Institutions and Book Culture

”Was there a Carolingian Italy?” Politics institutions and book culture François Bougard To cite this version: François Bougard. ”Was there a Carolingian Italy?” Politics institutions and book culture. Clemens Gantner; Walter Pohl. After Charlemagne: Carolingian Italy and its Rulers, Cambridge University Press, pp.54-82, 2020, 9781108840774. 10.1017/9781108887762.007. halshs-03080753 HAL Id: halshs-03080753 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03080753 Submitted on 16 Jul 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. [paru dans: After Charlemagne: Carolingian Italy and its Rulers, éd. Clemens Gantner et Walter Pohl, Cambridge Cambridge University Press, 2020, p. 54-82.] François Bougard ‘Was there a Carolingian Italy?’ Politics, institutions, and book culture* ‘The Carolingians in Italy’ is a literary myth. In order to account for the installation of the Franks on the Italian peninsula, our manuals have clung to a received vulgate. They assert that Pippin the Short and then Charlemagne allied themselves with the papacy, at the pope’s request, in order to stave off the Lombard threat against the Exarchate of Ravenna and defend the interests of the Holy See. But at the end of the tenth century, south of Rome, the story included other elements. -

Carolingian Propaganda: Kingship by the Hand of God

Isak M. C. Sexson Hist. 495 Senior Thesis Thesis Advisor: Martha Rampton April 24, 2000 Carolingian Propaganda: Kingship by the Hand of God Introduction and Thesis Topic: The Carolingians laid the foundation for their successful coup in 751 very carefully, using not only political and religious alliances, but also the written word to ensure a usurpation of Merovingian power. Up until, and even decades after Pippin III’s coup, the Carolingians used a written form of propaganda to solidify their claims to the throne and reinforce their already existent power base. One of the most successful, powerful and prominent features of the Carolingians’ propaganda campaign was their use of God and divine support. By divine support, I mean the Carolingians stressed their rightful place as rulers of Christiandom and were portrayed as both being aided in their actions by God and being virtuous and pious rulers. This strategy of claiming to fulfill Augustine’s vision of a “city of God” politically would eventually force the Carolingians into a tight corner during the troubled times of Louis the Pious. The Word Propaganda and Historiography: The word propaganda is a modern word which did not exist in Carolingian Europe. It carries powerful modern connotations and should not be applied lightly when discussing past documents without keeping its modern usage in mind at all times. As Hummel and Huntress note in their book The Analysis of Propaganda, “‘Propaganda’ is a 1 word of evil connotation . [and] the word has become a synonym for a lie.”1 In order to avoid the ‘evil connotations’ of modern propaganda in this paper I will limit my definition of propaganda to the intentional reproduction, distribution and exaggeration or fabrication of events in order to gain support. -

S.G. Chapter 13 Sec. 1

Study Guide Chp. 13 sec. 1 I. Complete terms and names sec. 1 1. What did the new society that emerged in Europe during the Middle Ages have its roots in? 2. When did the level of learning among the Romans start to sink sharply? 3. What happened to the knowledge of Greek? 4. By the 800’s what had evolved from Latin? 5. During a time of political chaos, what provided order and security? 6. What held Germanic society together? 7. What governed the small communities that Germanic peoples lived in? 8. What did Germanic warriors receive from the chief they followed? 9. What Germanic people held power in Gaul? 10. Who was their leader? What did he bring to the region? 11. Who supported Clovis’s military campaigns against other Germanic peoples? 12. What had Clovis accomplished by 511? 13. What religious communities did the church build to adapt to rural conditions? 14. What Italian monk and his sister developed a set of rules for monasteries and convents? 15. What did monks and nuns devote their lives to? 16. What did monasteries become? 17. What did Pope Gregory broaden? 18. What did Gregory use church revenue to do? 19. According to Gregory, what regions fell under his responsibility? 20. What would become a central theme of the Middle Ages? 21. What began to spring up all over Europe as the Roman Empire dissolved? 22. Who controlled the largest and strongest of Europe’s kingdoms? 23. By 700, what official had become the most powerful person in the Frankish kingdom? 24. -

Borna's Polity Attested by Frankish Sources in the Territory of the Former

International Symposium The Treaty of Aachen, AD 812: The Origins and Impact on the Region between the Adriatic, Central, and Southeastern Europe Abstracts University of Zadar Zadar, September 27–29, 2012 Abstracts of the International Symposium The Treaty of Aachen, AD 812: The Origins and Impact on the Region between the Adriatic, Central, and Southeastern Europe Zadar, September 27–29, 2012 University of Zadar Department of History 2012 Frankish ducatus or Slavic Chiefdom? The Character of Borna’s Polity in Early-Ninth-Century Dalmatia Denis Alimov Borna’s polity, attested by Frankish sources on the territory of the former Roman province of Dalmatia in the first quarter of the 9th century, is traditionally considered to be the cradle of early medieval Croatian state. Meanwhile, the exact character of this polity and the way it was linked with the Croats as an early medieval gens remain obscure in many respects. I argue that Borna’s ducatus consisted of two political entities, the Croat polity proper, with its heartland in the region of Knin, and a small chiefdom of the Guduscani in the region of Gacka. Borna was the chief of the Croats, a group of people that gradually developed into an ethnic unit under the leadership of a Christianized military elite.. For all that, the process of the stabilization of the Croats’ group identity originally connected with the social structures of Pax Avarica and its transformation into what can be called gentile identity was very durable, the rate of the process being considerably slower than the formation of supralocal political organization in Dalmatia. -

Approaches to Community and Otherness in the Late Merovingian and Early Carolingian Periods

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by White Rose E-theses Online Approaches to Community and Otherness in the Late Merovingian and Early Carolingian Periods Richard Christopher Broome Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2014 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Richard Christopher Broome to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2014 The University of Leeds and Richard Christopher Broome iii Acknowledgements There are many people without whom this thesis would not have been possible. First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor, Ian Wood, who has been a constant source of invaluable knowledge, advice and guidance, and who invited me to take on the project which evolved into this thesis. The project he offered me came with a substantial bursary, for which I am grateful to HERA and the Cultural Memory and the Resources of the Past project with which I have been involved. Second, I would like to thank all those who were also involved in CMRP for their various thoughts on my research, especially Clemens Gantner for guiding me through the world of eighth-century Italy, to Helmut Reimitz for sending me a pre-print copy of his forthcoming book, and to Graeme Ward for his thoughts on Aquitanian matters. -

Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the End of the Carolingian Empire Simon Maclean Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521819458 - Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the End of the Carolingian Empire Simon Maclean Index More information INDEX Aachen, 81, 120, 157, 188–9, 203, 224; see also Baldwinof Flanders, 117–18, 220 relics Bautier, Robert-Henri, 103, 110–11 Abbo of St-Germain, poet, 27, 36, 55–64, 82, Bavarian annalist, the, see Annals of Fulda 103, 106, 108 Beauvais, 107–8 Adalald, archbishop of Tours, 67 Belluno, see Haimo of Belluno Adalard, count of the palace, 117–18 Berardus, Italiancount, 70 Adalbert, count in Alemannia, 89–90 Berengar of Friuli, marchio, later king and Adalelm, count of Laon, 117–18 emperor, 28, 70–9, 92, 94–6, 113, 168, Adalgisus, count of Piacenza, 71, 72 181–2, 184, 220 Adalroch, missus, 71 Bernard, son of Charles the Fat, 123, 129–34, Ahab, 33 142, 143, 151, 152, 154, 159, 161, 167–9, Alanof Brittany, 154 172, 173–4, 182–3, 192–3, 197, 207, 211, Aletramnus, count in west Francia, 106, 116 212, 218–22, 227 Andernach, Battle of (876), 103, 133 Bernard Plantevelue of the Auvergne, marchio, Andlau, 172, 186, 188, 189, 191 69–70, 72–9, 115, 117 Andreas of Bergamo, historian, 62–3 Berthold, count of the palace, 185 Annals of Fulda, 23–47, 86, 97–8, 130, 131, 138, bishops, 204–13; see also Frotar of Bourges; 151, 174, 176–7, 190, 191, 195, 230 Gauzlin of St-Denis; Geilo of Langres; Annals of St-Bertin, 46 Haimo of Belluno; Liutbert of Mainz; Annals of St-Vaast, 36, 62, 100, 102, 125, 127 Liutward of Vercelli; Raino of Angers; anointing, see consecration Walter of Orleans;´