LECTURE 5 the Origins of Feudalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oxford Scholarship Online

Uses, Wills, and Fiscal Feudalism University Press Scholarship Online Oxford Scholarship Online The Oxford History of the Laws of England: Volume VI 1483–1558 John Baker Print publication date: 2003 Print ISBN-13: 9780198258179 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: March 2012 DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198258179.001.0001 Uses, Wills, and Fiscal Feudalism Sir John Baker DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198258179.003.0035 Abstract and Keywords This chapter examines property law related to uses, wills, and fiscal feudalism in England during the Tudor period. It discusses the conflict between landlords and tenants concerning land use, feoffment, and land revenue. The prevalence of uses therefore provoked a conflict of interests which could not be reduced to a simple question of revenue evasion. This was a major problem because during this period, the greater part of the land of England was in feoffments upon trust. Keywords: fiscal feudalism, land use, feoffments, property law, tenants, wills, landlords ANOTHER prolonged discussion, culminating in a more fundamental and far-reaching reform, concerned another class of tenant altogether, the tenant by knight-service. Here the debate concerned a different aspect of feudal tenure, the valuable ‘incidents’ which belonged to the lord on the descent of such a tenancy to an heir. The lord was entitled to Page 1 of 40 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2014. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use (for details see http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/page/privacy-policy). -

The Carolingian Past in Post-Carolingian Europe Simon Maclean

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 1 The Carolingian Past in Post-Carolingian Europe Simon MacLean On 28 January 893, a 13-year-old known to posterity as Charles III “the Simple” (or “Straightforward”) was crowned king of West Francia at the great cathedral of Rheims. Charles was a great-great-grandson in the direct male line of the emperor Charlemagne andclung tightly to his Carolingian heritage throughout his life.1 Indeed, 28 January was chosen for the coronation precisely because it was the anniversary of his great ancestor’s death in 814. However, the coronation, for all its pointed symbolism, was not a simple continuation of his family’s long-standing hegemony – it was an act of rebellion. Five years earlier, in 888, a dearth of viable successors to the emperor Charles the Fat had shattered the monopoly on royal authority which the Carolingian dynasty had claimed since 751. The succession crisis resolved itself via the appearance in all of the Frankish kingdoms of kings from outside the family’s male line (and in some cases from outside the family altogether) including, in West Francia, the erstwhile count of Paris Odo – and while Charles’s family would again hold royal status for a substantial part of the tenth century, in the long run it was Odo’s, the Capetians, which prevailed. Charles the Simple, then, was a man displaced in time: a Carolingian marooned in a post-Carolingian political world where belonging to the dynasty of Charlemagne had lost its hegemonic significance , however loudly it was proclaimed.2 His dilemma represents a peculiar syndrome of the tenth century and stands as a symbol for the theme of this article, which asks how members of the tenth-century ruling class perceived their relationship to the Carolingian past. -

Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History

SOME NOTES ON MANORS & MANORIAL HISTORY BY A. HAMILTON THOMPSON, M.A.. D.Litt.. F.B.A..F.S.A. Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History By A. Hamilton Thompson, M.A., D.Litt., F.B.A., F.S.A. The popular idea of a manor assumes that it is a fixed geo graphical area with definite boundaries, which belongs to a lord with certain rights over his tenants. In common usage, we speak of this or that lordship, almost in the same way in which we refer to a parish. It is very difficult, however, to give the word an exclusively geographical meaning. If we examine one of those documents which are known as Inquisitions post mortem, for example, we shall find that, at the death of a tenant who holds his property directly from the Crown, the king's escheator will make an extent, that is, a detailed valuation, of his manors. This will consist for the most part of a list of a number of holdings with names of the tenants, specifying the rent or other services due to the lord from each. These holdings will, it is true, be generally gathered together in one or more vills or townships, of which the manor may roughly be said to consist. But it will often be found that there are outlying holdings in other vills which owe service to a manor, the nucleus of which is at some distance. Thus the members of the manor of Rothley lay scattered at various distances from their centre, divided from it and from each other by other lordships. -

Francia. Band 44

Francia. Forschungen zur Westeuropäischen Geschichte. Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Paris (Institut historique allemand) Band 44 (2017) Nithard as a Military Historian of the Carolingian Empire, c 833–843 DOI: 10.11588/fr.2017.0.68995 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. Bernard S. Bachrach – David S. Bachrach NITHARD AS A MILITARY HISTORIAN OF THE CAROLINGIAN EMPIRE, C 833–843 Introduction Despite the substantially greater volume of sources that provide information about the military affairs of the ninth century as compared to the eighth, the lion’s share of scholarly attention concerning Carolingian military history has been devoted to the reign of Charlemagne, particularly before his imperial coronation in 800, rather than to his descendants1. Indeed, much of the basic work on the sources, that is required to establish how they can be used to answer questions about military matters in the period after Charlemagne, remains to be done. An unfortunate side-effect of this rel- ative neglect of military affairs as well as source criticism for the ninth century has been considerable confusion about the nature and conduct of war in this period2. -

Possibilities of Royal Power in the Late Carolingian Age: Charles III the Simple

Possibilities of royal power in the late Carolingian age: Charles III the Simple Summary The thesis aims to determine the possibilities of royal power in the late Carolingian age, analysing the reign of Charles III the Simple (893/898-923). His predecessors’ reigns up to the death of his grandfather Charles II the Bald (843-877) serve as basis for comparison, thus also allowing to identify mid-term developments in the political structures shaping the Frankish world toward the turn from the 9th to the 10th century. Royal power is understood to have derived from the interaction of the ruler with the nobles around him. Following the reading of modern scholarship, the latter are considered as partners of the former, participating in the royal decision-making process and at the same time acting as executors of these decisions, thus transmitting the royal power into the various parts of the realm. Hence, the question for the royal room for manoeuvre is a question of the relations between the ruler and the nobles around him. Accordingly, the analysis of these relations forms the core part of the study. Based on the royal diplomas, interpreted in the context of the narrative evidence, the noble networks in contact with the rulers are revealed and their influence examined. Thus, over the course of the reigns of Louis II the Stammerer (877-879) and his sons Louis III (879-882) and Carloman II (879-884) up until the rule of Charles III the Fat (884-888), the existence of first one, then two groups of nobles significantly influencing royal politics become visible. -

Capetian France (987–1328)

FORUM Capetian France (987–1328) Introduction Damien Kempf If “France is a creation of its medieval history,”1 the rule of the Cape- tian dynasty (987–1328) in particular is traditionally regarded as the beginning of France as a nation.2 Following the narrative established by Joseph Strayer’s influential bookOn the Medieval Origins of the Mod- ern State, historians situate the construction of the French nation- state in the thirteenth century, under the reigns of Philip Augustus (1180– 1223) and Louis IX (1226–70). Territorial expansion, the development of bureaucracy, and the centralization of the royal government all con- tributed to the formation of the state in France.3 Thus it is only at the end of a long process of territorial expansion and royal affirmation that the Capetian kings managed to turn what was initially a disparate and fragmented territory into a unified kingdom, which prefigured the modern state. In this teleological framework, there is little room or interest for the first Capetian kings. The eleventh and twelfth centuries are still described as the “âge des souverains,” a period of relative anarchy and disorder during which the aristocracy dominated the political land- scape and lordship was the “normative expression of human power.”4 Compared to these powerful lords, the early Capetians pale into insignifi- cance. They controlled a royal domain centered on Paris and Orléans and struggled to keep at bay the lords dominating the powerful sur- rounding counties and duchies. The famous anecdote reported by the Damien Kempf is senior lecturer in medieval history at the University of Liverpool. -

Glossar the Disintegration of the Carolingian Empire

Tabelle1 Bavaria today Germany’s largest state, located in the Bayern Southeast besiege, v surround with armed forces belagern Bretons an ethnic group located in the Northwest of Bretonen France Carpathian Mountains a range of mountains forming an arc of roughly Karpaten 1,500 km across Central and Eastern Europe, Charles the Fat (Charles III) 839 – 888, King of Alemannia from 876, King Karl III. of Italy from 879, Roman Emperor (as Charles III) from 881 Danelaw an area in England in which the laws of the Danelag Danes were enforced instead of the laws of the Anglo-Saxons Franconia today mainly a part of Bavaria, the medieval Franken duchy Franconia included towns such as Mainz and Frankfurt Henry I 876 – 936, the duke of Saxony from 912 and Heinrich I. king of East Francia from 919 until his death Huns a confederation of nomadic tribes that invaded Hunnen Europe around 370 AD Lombardy a region in Northern Italy Lombardei Lorraine a historical area in present-day Northeast Lothringen France, a part of the kingdom Lotharingia Lothar I (Lothair I) 795 – 855, the eldest son of the Carolingian Lothar I. emperor Louis I and his first wife Ermengarde, king of Italy (818 – 855), Emperor of the Franks (840 – 855) Lotharingia a kingdom in Western Europe, it existed from Lothringen 843 – 870; not to be confused with Lorraine Louis I (Louis the Pious 778 – 840, also called the Fair, and the Ludwig I. Debonaire; only surviving son of Charlemagne; King of the Franks Louis the German (Louis II) ca. 806 – 876, third son of Louis I, King of Ludwig der Bavaria (817 – 876) and King of East Francia Deutsche (843 – 876) Louis the Younger (Louis III) 835 – 882, son of Louis the German, King of Ludwig III., der Saxony (876-882) and King of Bavaria (880- Jüngere 882), succeeded by his younger brother, Charles the Fat, Magyars an ethnic group primarily associated with Ungarn Hungary. -

9780521564946 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-56494-6 - The Carolingian World Marios Costambeys, Matthew Innes and Simon Maclean Index More information INDEX . Aachen on conversion of Avars and Saxons, and memory of Charlemagne, 5 108 Charlemagne’s burial place, 154, 197 on force and conversion, 74 palace complex and chapel, 77, 157, on imperium, 166 168, 169, 173, 174, 175, 178, 196, 197, on pope and emperor, 138 199, 201, 205, 213, 214, 217, 218, 282, on the virtues and vices, 300 293, 295, 320, 409, 411, 420, 425 relationship to Willibrord, 106 Abbo of St-Germain-des-Pres:´ on Viking Alemannia. See also Judith, Empress; attack on Paris, 277 Charles the Fat Adalhard, Charlemagne’s cousin, 193 and Carolingian conquest, 225 and Hincmar’s De ordine palatii [On the and Charles Martel, 46 Governance of the Palace], 295 and family of Empress Judith, 206 and succession of Louis the Pious, 199 and opposition to rehabilitated in 820s, 206 Carolingians, 41, 51 afterlife: ideas of, 115 and Pippin III, 52 Agnellus of Ravenna, 59 conquest under Carloman and Pippin Agobard of Lyon III, 52 controversy with Amalarius of Metz, Merovingian conquest, 35 121 under Charlemagne, 66 criticism of Matfrid’s influence, 213 Amalarius of Metz on Jewish slave traders, 367 on Mass, 121 Aistulf, Lombard king, 58, 62 annals, 22, 23 laws on merchants, 368 and Pippin’s seizure of kingship, 32 military legislation of, 279 production of, 18, 21 Alcuin Annals of Fulda, 23, 231, 387, 396, as scholar, 143 404 as teacher, 147 Annals of Lorsch, 23, 166 asks ‘what has Ingeld to do with -

Farwell to Feudalism

Burke's Landed Gentry - The Kingdom in Scotland This pdf was generated from www.burkespeerage.com/articles/scotland/page14e.aspx FAREWELL TO FEUDALISM By David Sellar, Honorary Fellow, Faculty of Law, University of Edinburgh "The feudal system of land tenure, that is to say the entire system whereby land is held by a vassal on perpetual tenure from a superior is, on the appointed day, abolished". So runs the Sixth Act to be passed in the first term of the reconvened Scottish Parliament, The Abolition of Feudal Tenure etc (Scotland) Act 2000. The Act is welcome. By the end of the second millennium the feudal system had long outlived its usefulness, even as a legal construct, and had few, if any defenders. As the Scottish Law Commission commented in 1999, "The main reason for recommending the abolition of the feudal system of land tenure is that it has degenerated from a living system of land tenure with both good and bad features into some-thing which, in the case of many but not all superiors, is little more than an instrument for extracting money". The demise of feudalism brings to an end a story which began almost a thousand years ago, and which has involved all of Scotland's leading families. In England the advent of feudalism is often associated with the Norman Conquest of 1066. That Conquest certainly marked a new beginning in landownership which paved the way for the distinctive Anglo-Norman variety of feudalism. There was a sudden and virtually clean sweep of the major landowners. By the date of the Domesday Survey in 1086, only two major landowners of pre-Conquest vintage were left south of the River Tees holding their land direct of the crown: Thurkell of Arden (from whom the Arden family descend), and Colswein of Lincoln. -

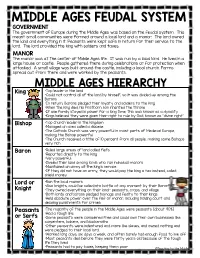

FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT the Government of Europe During the Middle Ages Was Based on the Feudal System

MIDDLE AGES FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT The government of Europe during the Middle Ages was based on the feudal system. This meant small communities were formed around a local lord and a manor. The lord owned the land and everything in it. Peasants were kept safe in return for their service to the lord. The lord provided the king with soldiers and taxes. MANOR The manor was at the center of Middle Ages life. It was run by a local lord. He lived in a large house or castle. People gathered there during celebrations or for protection when attacked. A small village was built around the castle, including a local church. Farms spread out from there and were worked by the peasants. MIDDLE AGES HIERARCHY King *Top leader in the land *Could not control all of the land by himself, so it was divided up among the Barons *In return, Barons pledged their loyalty and soldiers to the king *When the king died, his firstborn son inherited the throne *If one family stayed in power for a long time, this was known as a dynasty *Kings believed they were given their right to rule by God, known as “divine right” Bishop *Top church leader in the kingdom *Managed an area called a diocese *The Catholic Church was very powerful in most parts of Medieval Europe, making the Bishop powerful *The Church received a tithe of 10 percent from all people, making some Bishops very rich Baron *Ruled large areas of land called fiefs *Reported directly to the king *Very powerful *Divided their land among lords who ran individual manors *Maintained an army at the king’s service *If -

Merovingian Queens: Status, Religion, and Regency

Merovingian Queens: Status, Religion, and Regency Jackie Nowakowski Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of History, Georgetown University Advisor: Professor Jo Ann Moran Cruz Honors Program Chair: Professor Alison Games May 4, 2020 Nowakowski 1 Table of Contents: Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………………………..2 Map, Genealogical Chart, Glossary……………………………………………………………3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………7 Chapter 1: The Makings of a Merovingian Queen: Slave, Concubine, or Princess………..18 Chapter 2: Religious Authority of Queens: Intercessors and Saints………………………..35 Chapter 3: Queens as Regents: Scheming Stepmothers and Murdering Mothers-in-law....58 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………....80 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………….83 Nowakowski 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Moran Cruz for all her guidance and advice; you have helped me become a better scholar and writer. I also want to thank Professor Games for your constant enthusiasm and for creating a respectful and fun atmosphere for our seminar. Your guidance over these past two semesters have been invaluable. I am also so grateful for my classmates, who always gave me honest and constructive feedback; I have enjoyed seeing where your projects take you. Most of all, I would like to thank my family and friends for listening to me talk nonstop about a random, crazy, dysfunctional family from the sixth century. I am incredibly thankful for my parents, sister, and friends for their constant support. Thank you mom for listening to a podcast on the Merovingians so you could better understand what I am studying. You have always inspired me to work hard and I probably wouldn’t have written a thesis without you as my inspiration. I also want to thank my dad, who always supported my studies and pretended to know more about a topic than he actually did. -

Selected Ancestors of the Chicago Rodger's

Selected Ancestors of the Chicago Rodger’s Volume I: Continental Ancestors Before Hastings David Anderson March 2016 Charlemagne’s Europe – 800 AD For additional information, please contact David Anderson at: [email protected] 508 409 8597 Stained glass window depicting Charles Martel at Strasbourg Cathedral. Pepin shown standing Pepin le Bref Baldwin II, Margrave of Flanders 2 Continental Ancestors Before Hastings Saints, nuns, bishops, brewers, dukes and even kings among them David Anderson March 12, 2016 Abstract Early on, our motivation for studying the ancestors of the Chicago Rodger’s was to determine if, according to rumor, they are descendants of any of the Scottish Earls of Bothwell. We relied mostly on two resources on the Internet: Ancestry.com and Scotlandspeople.gov.uk. We have been subscribers of both. Finding the ancestral lines connecting the Chicago Rodger’s to one or more of the Scottish Earls of Bothwell was the most time consuming and difficult undertaking in generating the results shown in a later book of this series of three books. It shouldn’t be very surprising that once we found Earls in Scotland we would also find Kings and Queens, which we did. The ancestral line that connects to the Earls of Bothwell goes through Helen Heath (1831-1902) who was the mother and/or grandmother of the Chicago Rodger’s She was the paternal grandmother of my grandfather, Alfred Heath Rodger. Within this Heath ancestral tree we found four lines of ancestry without any evident errors or ambiguities. Three of those four lines reach just one Earl of Bothwell, the 1st, and the fourth line reaches the 1st, 2nd and 3rd.