Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maternity's Wards: Investigations of Sixteenth Century Patterns of Maternal Gaurdianship

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU History Graduate Studies 2003 Maternity's Wards: Investigations Of Sixteenth Century Patterns Of Maternal Gaurdianship Liz Woolcott Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd_history Part of the History of Gender Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Woolcott, Liz, "Maternity's Wards: Investigations Of Sixteenth Century Patterns Of Maternal Gaurdianship" (2003). History. 1. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd_history/1 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MATERNITY'S WARDS: INVESTIGATIONS OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY PATTERNS OF MATERNAL GUARDIANSHIP by Elizabeth B. W oolcott A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS In HISTORY Approved: Dr. Norman Jones D~. Robert ijueller Major Professor Committee Member . Dr.,Nancy~~ V :m?fflo-;nas L. Ke~;· Committee~ber Dean of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Log~ Utah 2003 11 Copyright © Elizabeth B. Woolcott 2003 All Rights Reserved 111 ABSTRACT Maternity' s Wards: Investigations Of Sixteenth Century Patterns of Maternal Guardianship by Elizabeth B. Woolcott, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2003 Major Professor: Dr. Nonnan Jones Department: History Grants of wardship, by the time of the Tudor period in England, had evolved into an institution divorced from its feudal foundation but committed to maintaining a goal of economic profit. Mixed with a pronounced responsibility of the monarch to care for the unprotected children of deceased feudatories, this goal compromised the practice of wardship grants and created a bureaucracy whose sole policy was patronage. -

LECTURE 5 the Origins of Feudalism

OUTLINE — LECTURE 5 The Origins of Feudalism A Brief Sketch of Political History from Clovis (d. 511) to Henry IV (d. 1106) 632 death of Mohammed The map above shows to the growth of the califate to roughly 750. The map above shows Europe and the East Roman Empire from 533 to roughly 600. – 2 – The map above shows the growth of Frankish power from 481 to 814. 486 – 511 Clovis, son of Merovich, king of the Franks 629 – 639 Dagobert, last effective Merovingian king of the Franks 680 – 714 Pepin of Heristal, mayor of the palace 714 – 741 Charles Martel, mayor (732(3), battle of Tours/Poitiers) 714 – 751 - 768 Pepin the Short, mayor then king 768 – 814 Charlemagne, king (emperor, 800 – 814) 814 – 840 Louis the Pious (emperor) – 3 – The map shows the Carolingian empire, the Byzantine empire, and the Califate in 814. – 4 – The map shows the breakup of the Carolingian empire from 843–888. West Middle East 840–77 Charles the Bald 840–55 Lothair, emp. 840–76 Louis the German 855–69 Lothair II – 5 – The map shows the routes of various Germanic invaders from 150 to 1066. Our focus here is on those in dark orange, whom Shepherd calls ‘Northmen: Danes and Normans’, popularly ‘Vikings’. – 6 – The map shows Europe and the Byzantine empire about the year 1000. France Germany 898–922 Charles the Simple 919–36 Henry the Fowler 936–62–73 Otto the Great, kg. emp. 973–83 Otto II 987–96 Hugh Capet 983–1002 Otto III 1002–1024 Henry II 996–1031 Robert II the Pious 1024–39 Conrad II 1031–1060 Henry I 1039–56 Henry III 1060–1108 Philip I 1056–1106 Henry IV – 7 – The map shows Europe and the Mediterranean lands in roughly the year 1097. -

The History of Luttrellstown Demesne, Co. Dublin

NORTHERN IRELAND HERITAGE GARDENS TRUST OCCASIONAL PAPER, No 4 (2015) 'Without Rival in our Metropolitan County' - The History of Luttrellstown Demesne, Co. Dublin Terence Reeves-Smyth Luttrellstown demesne, which occupies around 600 acres within its walls, has long been recognised as the finest eighteenth century landscape in County Dublin and one of the best in Ireland. Except for the unfortunate incorporation of a golf course into the eastern portion of its historic parkland, the designed landscape has otherwise survived largely unchanged for over two centuries. With its subtle inter-relationship of tree belts and woodlands, its open spaces and disbursement of individual tree specimens, together with its expansive lake, diverse buildings and its tree-clad glen, the demesne, known as 'Woodlands' in the 19th century, was long the subject of lavish praise and admiration from tourists and travellers. As a writer in the Irish Penny Journal remarked in October 1840: ‘considered in connection with its beautiful demesne, [Luttrellstown] may justly rank as the finest aristocratic residence in the immediate vicinity of our metropolis.. in its natural beauties, the richness of its plantations and other artificial improvements, is without rival in our metropolitan county, and indeed is characterised by some features of such exquisite beauty as are rarely found in park scenery anywhere, and which are nowhere to be surpassed’.1 Fig 1. 'View on approaching Luttrellstown Park', drawn & aquatinted by Jonathan Fisher; published as plate 6 in Scenery -

Feudalism Manors

effectively defend their lands from invasion. As a result, people no longer looked to a central ruler for security. Instead, many turned to local rulers who had their Recognizing own armies. Any leader who could fight the invaders gained followers and politi- Effects cal strength. What was the impact of Viking, Magyar, and A New Social Order: Feudalism Muslim invasions In 911, two former enemies faced each other in a peace ceremony. Rollo was the on medieval head of a Viking army. Rollo and his men had been plundering the rich Seine (sayn) Europe? River valley for years. Charles the Simple was the king of France but held little power. Charles granted the Viking leader a huge piece of French territory. It became known as Northmen’s land, or Normandy. In return, Rollo swore a pledge of loyalty to the king. Feudalism Structures Society The worst years of the invaders’ attacks spanned roughly 850 to 950. During this time, rulers and warriors like Charles and Rollo made similar agreements in many parts of Europe. The system of governing and landhold- ing, called feudalism, had emerged in Europe. A similar feudal system existed in China under the Zhou Dynasty, which ruled from around the 11th century B.C.until 256 B.C.Feudalism in Japan began in A.D.1192 and ended in the 19th century. The feudal system was based on rights and obligations. In exchange for military protection and other services, a lord, or landowner, granted land called a fief.The person receiving a fief was called a vassal. -

B. Medieval Manorialism and Peasant Serfdom: the Agricultural Foundations of Medieval Feudalism Revised 21 October 2013

III. BARRIERS TO ECONOMIC GROWTH IN THE MEDIEVAL ECONOMY: B. Medieval Manorialism and Peasant Serfdom: the Agricultural Foundations of Medieval Feudalism revised 21 October 2013 Manorialism: definitions • (1) a system of dependent peasant cultivation, • in which a community of peasants, ranging from servile to free, received their lands or holdings from a landlord • - usually a feudal, military lord • (2) the peasants: worked those lands at least in part for the lord’s economic benefit • - in return for both economic and military security in holding their tenancy lands from that military lord. Medieval Manorialism Key Features • (1) European manorialism --- also known as seigniorialism [seignior, seigneur = lord] both predated and outlived feudalism: predominant agrarian socio-economic institution from 4th-18th century • (2) Medieval manorialism: links to Feudalism • The manor was generally a feudal fief • i.e., a landed estate held by a military lord in payment and reward for military services • Feudal fiefs were often collections of manors, • servile peasants provided most of labour force in most northern medieval manors (before 14th century) THE FEUDAL LORD OF THE MANOR • (1) The Feudal Lord of the Manor: almost always possessed judicial powers • secular lord: usually a feudal knight (or superior lord: i.e., count or early, duke, etc.); • ecclesiastical lord: a bishop (cathedral); abbot (monastery); an abbess (nunnery) • (2) Subsequent Changes: 15th – 18th centuries • Many manors, in western Europe, passed into the hands of non-feudal -

STATUTE QUIA EMPTORES (1290) Statutes of the Realm, Vol

STATUTE QUIA EMPTORES (1290) Statutes of the Realm, vol. I, p . I 06. Whereas the buyers of lands and tenements belonging to the fees of great men and other [lords] have in times past often entered [those] fees to [the lords'] prejudice, because tenants holding freely of those great men and other [lords] have sold their lands and tenements [to those buyers] to hold in fee to [the buyers] and their heirs of their feoffors and not of the chief lords of the fees, with the result that the same chief lords have often lost the escheats, marriages and wardships of lands and tenements belonging to their fees; and this has seemed to the same great men and other lords [not only] very bard and burdensome [but also] in such a case to their manifest disinheritance: The lord king in his parliament at Westminster after Easter in 10 Tenure: services and incidents the eighteenth. year of his reign, namely a fortnight after the feast of St John the Baptist, at the instance of the great men of his realm, has granted, provided and laid down that from henceforth it shall be lawful for any free man at his own pleasure to sell his lands or tenements or [any] part of them; provided however that the feoffee shall hold those lands or tenements of the same chief lord and by the same services and customary dues as his feoffor previously held them. And if he sells to another any part of his same lands or tenements, the feoffee shall hold that [part] directly of the chief lord and shall immediately be burdened with such amount of service as belongs or ought to belong to the same lord for that part according to the amount of the land or tenement [that has been] sold; and so in this case that part of the service falls to the chief lord to be taken by the hand of the [feoffee], so that the feoffee ought to look and answer to the same chief lord for that part of the service owed as [is proportional to] the amount of the land or tenement sold. -

Wakefield, West Riding: the Economy of a Yorkshire Manor

WAKEFIELD, WEST RIDING: THE ECONOMY OF A YORKSHIRE MANOR By BRUCE A. PAVEY Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1991 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1993 OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY WAKEFIELD, WEST RIDING: THE ECONOMY OF A YORKSHIRE MANOR Thesis Approved: ~ ThesiSAd er £~ A J?t~ -Dean of the Graduate College ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply indebted to to the faculty and staff of the Department of History, and especially the members of my advisory committee for the generous sharing of their time and knowledge during my stay at O.S.U. I must thank Dr. Alain Saint-Saens for his generous encouragement and advice concerning not only graduate work but the historian's profession in general; also Dr. Joseph Byrnes for so kindly serving on my committee at such short notice. To Dr. Ron Petrin I extend my heartfelt appreciation for his unflagging concern for my academic progress; our relationship has been especially rewarding on both an academic and personal level. In particular I would like to thank my friend and mentor, Dr. Paul Bischoff who has guided my explorations of the medieval world and its denizens. His dogged--and occasionally successful--efforts to develop my skills are directly responsible for whatever small progress I may have made as an historian. To my friends and fellow teaching assistants I extend warmest thanks for making the past two years so enjoyable. For the many hours of comradeship and mutual sympathy over the trials and tribulations of life as a teaching assistant I thank Wendy Gunderson, Sandy Unruh, Deidre Myers, Russ Overton, Peter Kraemer, and Kelly McDaniels. -

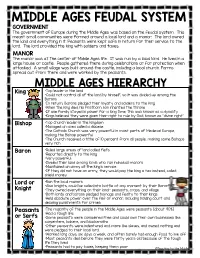

FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT the Government of Europe During the Middle Ages Was Based on the Feudal System

MIDDLE AGES FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT The government of Europe during the Middle Ages was based on the feudal system. This meant small communities were formed around a local lord and a manor. The lord owned the land and everything in it. Peasants were kept safe in return for their service to the lord. The lord provided the king with soldiers and taxes. MANOR The manor was at the center of Middle Ages life. It was run by a local lord. He lived in a large house or castle. People gathered there during celebrations or for protection when attacked. A small village was built around the castle, including a local church. Farms spread out from there and were worked by the peasants. MIDDLE AGES HIERARCHY King *Top leader in the land *Could not control all of the land by himself, so it was divided up among the Barons *In return, Barons pledged their loyalty and soldiers to the king *When the king died, his firstborn son inherited the throne *If one family stayed in power for a long time, this was known as a dynasty *Kings believed they were given their right to rule by God, known as “divine right” Bishop *Top church leader in the kingdom *Managed an area called a diocese *The Catholic Church was very powerful in most parts of Medieval Europe, making the Bishop powerful *The Church received a tithe of 10 percent from all people, making some Bishops very rich Baron *Ruled large areas of land called fiefs *Reported directly to the king *Very powerful *Divided their land among lords who ran individual manors *Maintained an army at the king’s service *If -

Statutes As Judgments: the Natural Law Theory of Parliamentary Activity in Medieval England*

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Indiana University Bloomington Maurer School of Law Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 1977 Statutes as Judgments: The aN tural Law Theory of Parliamentary Activity in Medieval England Morris S. Arnold Indiana University School of Law - Bloomington Follow this and additional works at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Legal History Commons, and the Natural Law Commons Recommended Citation Arnold, Morris S., "Statutes as Judgments: The aN tural Law Theory of Parliamentary Activity in Medieval England" (1977). Articles by Maurer Faculty. Paper 1136. http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/1136 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1977] STATUTES AS JUDGMENTS: THE NATURAL LAW THEORY OF PARLIAMENTARY ACTIVITY IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND* MORRIS S. ARNOLD t The proposition that late medieval English lawgivers believed themselves to be exercising a declarative function has been so fre- quently put forward and so widely accepted that it is in danger of being canonized by sheer dint of repetition; 1 and thus one who would deny the essential validity of that notion bears the virtually insuperable burden of proof commonly accorded an accused heretic. Nevertheless, it will be argued here that natural law notions are attributed to the medieval English legislator with only the slightest support from the sources, and after only the most rudimentary and uncritical analyses of the implications of such an idea. -

Future Interests in Property in Minnesota Everett Rf Aser

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1919 Future Interests in Property in Minnesota Everett rF aser Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Fraser, Everett, "Future Interests in Property in Minnesota" (1919). Minnesota Law Review. 1283. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/1283 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MINNESOTA LAW REVIEW FUTURE INTERESTS IN PROPERTY IN MINNESOTA "ORIGINALLY the creation of future interests at law was greatly restricted, but now, either by the Statutes of Uses and of Wills, or by modern legislation, or by the gradual action of the courts, all restraints on the creation of future interests, except those arising from remoteness, have been done away. This practically reduces the law restricting the creation of future interests to the Rule against Perpetuities,"' Generally in common law jurisdictions today there is but one rule restricting the crea- tion of future interests, and that rule is uniform in its application to real property and to personal property, to legal and equitable interests therein, to interests created by way of trust, and to powers. In 1830 the New York Revised Statutes went into effect in New York state. The revision had been prepared by a commis- sion appointed for the purpose five years before. It contained a code of property law in which "the revisers undertook to re- write the whole law of future estates in land, uses and trusts .. -

Notes on the Lancaster Estates in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries

NOTES ON THE LANCASTER ESTATES IN THE THIRTEENTH AND FOURTEENTH CENTURIES BY DOROTHEA OSCHINSKY, D.Phil., Ph.D. Read 24 April 1947 UR knowledge of mediaeval estate administration is O based mainly on sources which relate to ecclesiastical estates, because these are easier of access and, as a rule, more complete. The death of an abbot affected a monastic estate only in so far as his successor might be a better or a worse husbandman; the estate was never divided between heirs, was not diminished by the endowment of widows and daughters, and was not doubled by prudent marriages as were seignorial estates. Furthermore, the ecclesiastics had frequently been granted their lands in frankalmoin, and no rent or service was rendered in return. With few exceptions their manors lay near the centre of the estate; and, finally, the clerics had sufficient leisure to supervise their estates themselves and little difficulty in providing a staff trained to work the estates intensively and profitably. Therefore we realise that any conclusions which are based on ecclesiastical estates only must necessarily be one-sided, and that before we can draw a general picture of the estate administration in the Middle Ages, we have to work out the estate adminis tration on at least some of the more important seignorial estates. The Lancaster estates with their changing fate are well able to reveal the chief characteristics of a seignorial estate, its extent, management and administration. The vastness of the estates of the Earls of Lancaster, and the importance of the family in the political history of the country, accen tuated and multiplied the difficulties of the estate adminis tration. -

Dickinson Law Review - Volume 21, Issue 1

Volume 21 Issue 1 1-1916 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 21, Issue 1 Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Dickinson Law Review - Volume 21, Issue 1, 21 DICK. L. REV. 1 (2020). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol21/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dickinson Law Review VOL. XXI OCTOBER, 1916 No. 1 BUSINESS MANAGERS EDITORS John D. M. Royal, '17 Henry M. Bruner, '17 Lawrence D. Savige, '17 Edward H. Smith, '17 John H. Bonin, '17 William Lurio, '17 Joseph C. Paul, '18 Ethel Holderbaum, '18 Subscription $1.60 per annum, payable in advance WALLACE vs. EDWIN HARMSTAD, 44 PA. 492 In 1838 Arrison sold to four brothers Harmstad four adjoining lots, reserving out o2 each a yearly rent of !$60, payable half-yearly, in January and July. Each grantee, entered on his lot and built a house on it. The deeds were executed in duplicate each being signed by both parties. A part of the bargain was that the rents might be redeemed at any time. In the deeds was a blank with respect to the time of redemption, which was explained by Arrison as meaning that there was no limit of time. Some time after the delivery of the deeds, they were procured by Ar- rison for the alleged purpose of having them recorded, and while out of the possession of the Harmstads the blanks were filled with the words, "within ten years from the date thereof," making redemption after ten years impos- sible.