Dickinson Law Review - Volume 21, Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oxford Scholarship Online

Uses, Wills, and Fiscal Feudalism University Press Scholarship Online Oxford Scholarship Online The Oxford History of the Laws of England: Volume VI 1483–1558 John Baker Print publication date: 2003 Print ISBN-13: 9780198258179 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: March 2012 DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198258179.001.0001 Uses, Wills, and Fiscal Feudalism Sir John Baker DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198258179.003.0035 Abstract and Keywords This chapter examines property law related to uses, wills, and fiscal feudalism in England during the Tudor period. It discusses the conflict between landlords and tenants concerning land use, feoffment, and land revenue. The prevalence of uses therefore provoked a conflict of interests which could not be reduced to a simple question of revenue evasion. This was a major problem because during this period, the greater part of the land of England was in feoffments upon trust. Keywords: fiscal feudalism, land use, feoffments, property law, tenants, wills, landlords ANOTHER prolonged discussion, culminating in a more fundamental and far-reaching reform, concerned another class of tenant altogether, the tenant by knight-service. Here the debate concerned a different aspect of feudal tenure, the valuable ‘incidents’ which belonged to the lord on the descent of such a tenancy to an heir. The lord was entitled to Page 1 of 40 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2014. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use (for details see http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/page/privacy-policy). -

Shattering and Moving Beyond the Gutenberg Paradigm: the Dawn of the Electronic Will

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 42 2008 Shattering and Moving Beyond the Gutenberg Paradigm: The Dawn of the Electronic Will Joseph Karl Grant Capital University Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph K. Grant, Shattering and Moving Beyond the Gutenberg Paradigm: The Dawn of the Electronic Will, 42 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 105 (2008). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol42/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHATTERING AND MOVING BEYOND THE GUTENBERG PARADIGM: THE DAWN OF THE ELECTRONIC WILL Joseph Karl Grant* INTRODUCTION Picture yourself watching a movie. In the film, a group of four siblings are dressed in dark suits and dresses. The siblings, Bill Jones, Robert Jones, Margaret Jones and Sally Johnson, have just returned from their elderly mother's funeral. They sit quietly in their mother's attorney's office intently watching and listening to a videotape their mother, Ms. Vivian Jones, made before her death. On the videotape, Ms. Jones expresses her last will and testament. Ms. Jones clearly states that she would like her sizable real estate holdings to be divided equally among her four children and her valuable blue-chip stock investments to be used to pay for her grandchildren's education. -

LECTURE 5 the Origins of Feudalism

OUTLINE — LECTURE 5 The Origins of Feudalism A Brief Sketch of Political History from Clovis (d. 511) to Henry IV (d. 1106) 632 death of Mohammed The map above shows to the growth of the califate to roughly 750. The map above shows Europe and the East Roman Empire from 533 to roughly 600. – 2 – The map above shows the growth of Frankish power from 481 to 814. 486 – 511 Clovis, son of Merovich, king of the Franks 629 – 639 Dagobert, last effective Merovingian king of the Franks 680 – 714 Pepin of Heristal, mayor of the palace 714 – 741 Charles Martel, mayor (732(3), battle of Tours/Poitiers) 714 – 751 - 768 Pepin the Short, mayor then king 768 – 814 Charlemagne, king (emperor, 800 – 814) 814 – 840 Louis the Pious (emperor) – 3 – The map shows the Carolingian empire, the Byzantine empire, and the Califate in 814. – 4 – The map shows the breakup of the Carolingian empire from 843–888. West Middle East 840–77 Charles the Bald 840–55 Lothair, emp. 840–76 Louis the German 855–69 Lothair II – 5 – The map shows the routes of various Germanic invaders from 150 to 1066. Our focus here is on those in dark orange, whom Shepherd calls ‘Northmen: Danes and Normans’, popularly ‘Vikings’. – 6 – The map shows Europe and the Byzantine empire about the year 1000. France Germany 898–922 Charles the Simple 919–36 Henry the Fowler 936–62–73 Otto the Great, kg. emp. 973–83 Otto II 987–96 Hugh Capet 983–1002 Otto III 1002–1024 Henry II 996–1031 Robert II the Pious 1024–39 Conrad II 1031–1060 Henry I 1039–56 Henry III 1060–1108 Philip I 1056–1106 Henry IV – 7 – The map shows Europe and the Mediterranean lands in roughly the year 1097. -

Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History

SOME NOTES ON MANORS & MANORIAL HISTORY BY A. HAMILTON THOMPSON, M.A.. D.Litt.. F.B.A..F.S.A. Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History By A. Hamilton Thompson, M.A., D.Litt., F.B.A., F.S.A. The popular idea of a manor assumes that it is a fixed geo graphical area with definite boundaries, which belongs to a lord with certain rights over his tenants. In common usage, we speak of this or that lordship, almost in the same way in which we refer to a parish. It is very difficult, however, to give the word an exclusively geographical meaning. If we examine one of those documents which are known as Inquisitions post mortem, for example, we shall find that, at the death of a tenant who holds his property directly from the Crown, the king's escheator will make an extent, that is, a detailed valuation, of his manors. This will consist for the most part of a list of a number of holdings with names of the tenants, specifying the rent or other services due to the lord from each. These holdings will, it is true, be generally gathered together in one or more vills or townships, of which the manor may roughly be said to consist. But it will often be found that there are outlying holdings in other vills which owe service to a manor, the nucleus of which is at some distance. Thus the members of the manor of Rothley lay scattered at various distances from their centre, divided from it and from each other by other lordships. -

Norms, Formalities, and the Statute of Frauds: a Comment

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1996 Norms, Formalities, and the Statute of Frauds: A Comment Eric A. Posner Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Eric Posner, "Norms, Formalities, and the Statute of Frauds: A Comment," 144 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 1971 (1996). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NORMS, FORMALITIES, AND THE STATUTE OF FRAUDS: A COMMENT ERIC A. POSNERt INTRODUCTION Jason Johnston's Article makes three contributions to the economics and sociology of contract law.' First, it provides a methodological analysis of the use of case reports to discover business norms. Second, it makes a positive argument about the extent to which businesses use writings in contractual relations. Third, it sets the stage for, and hints at, a normative defense of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) section 2-201. Although the first contribution is probably the most interesting and useful, I focus on the second and third, and comment only in passing on the first. I conclude with some observations about the role of formalities in contract law. I. JOHNSTON'S POSITIVE ANALYSIS A. The Hypothesis Johnston's hypothesis is that "strangers" use writings for the purpose of ensuring legal enforcement. "Repeat players" do not use writings for this purpose because they expect that nonlegal sanctions will deter breach. -

United States District Court Southern District of Indiana New Albany Division

Case 4:06-cv-00074-JDT-WGH Document 45 Filed 08/07/07 Page 1 of 19 PageID #: <pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA NEW ALBANY DIVISION MADISON TOOL AND DIE, INC., ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) vs. ) 4:06-cv-0074-JDT-WGH ) ) ZF SACHS AUTOMOTIVE OF AMERICA, ) INC., ) ) Defendant. ) ENTRY ON DEFENDANT’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND MOTION TO STRIKE JURY DEMAND (Docs. No. 21 & 29)1 This matter comes before the court on Defendant’s Motion for Summary Judgment and Motion to Strike Jury Demand. (Docs. No. 21 & 29.) Plaintiff Madison Tool and Die, Inc. (“Madison”) filed this cause in Jefferson County, Indiana, Circuit Court alleging that Defendant ZF Sachs Automotive of America, Inc. (“Sachs”) breached a contract under which Madison was to supply parts to Sachs. On May 11, 2006, Defendant removed this case to United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana. (Doc. No. 1.) (The parties are diverse and the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000.) On March 22, 2007, Defendant filed a motion for summary judgment alleging that the Indiana Statute of Frauds (“Statute of Frauds” or “Statute”) rendered the alleged oral contract unenforceable and that promissory estoppel does not take this oral 1 This Entry is a matter of public record and will be made available on the court’s web site. However, the discussion contained herein is not sufficiently novel to justify commercial publication. Case 4:06-cv-00074-JDT-WGH Document 45 Filed 08/07/07 Page 2 of 19 PageID #: <pageID> contract or promise outside the operation of the Statute. -

Estoppel to Avoid the California Statute of Frauds Philip H

McGeorge Law Review Volume 35 | Issue 3 Article 4 1-1-2004 Estoppel to Avoid the California Statute of Frauds Philip H. Wile University of the Pacific; cGeM orge School of Law Kathleen Cordova-Lyon University of the Pacific; cGeM orge School of Law Claude D. Rohwer University of the Pacific; cGeM orge School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Philip H. Wile, Kathleen Cordova-Lyon & Claude D. Rohwer, Estoppel to Avoid the California Statute of Frauds, 35 McGeorge L. Rev. 319 (2004). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/mlr/vol35/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Law Reviews at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in McGeorge Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Estoppel to Avoid the California Statute of Frauds Philip H. Wile,* Kathleen C6rdova-Lyon** and Claude D. Rohwer*** TABLE OF CONTENTS I. THE STATUTE OF FRAUDS AND EQUITABLE ESTOPPEL ............................ 321 II. SEYMOUR AND ITS PROGENY ..................................................................... 325 III. THE IMPACT OF THESE INROADS ON THE STATUTE OF FRAUDS .............. 337 IV. THE UNJUST ENRICHMENT CASES ............................................................ 341 V. FULLER'S THREE FUNCTIONS REVISITED ................................................. 344 VI. MONARCO AND ITS PROGENY .................................................................... 344 V II. THE BROKER CASES ................................................................................. 355 VIII. THE STATUTE OF FRAUDS IN ARTICLE 2 .................................................. 363 IX. THE CALIFORNIA PRINCIPLES AND THE RESTATEMENT ........................... 364 The statute of frauds was enacted to prevent fraud.' The statute of frauds 2 cannot properly be asserted as a defense when to do so would perpetrate a fraud. -

English Contract Law: Your Word May Still Be Your Bond Oral Contracts Are Alive and Well – and Enforceable

Client Alert Litigation Client Alert Litigation March 13, 2014 English Contract Law: Your Word May Still be Your Bond Oral contracts are alive and well – and enforceable. By Raymond L. Sweigart American movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn is widely quoted as having said, ‘A verbal contract isn’t worth the paper it’s written on.’ He is also reputed to have stated, ‘I’m willing to admit that I may not always be right, but I am never wrong.’ With all due respect to Mr Goldwyn, he did not have this quite right and recent case law confirms he actually had it quite wrong. English law on oral contracts has remained essentially unchanged with a few exceptions for hundreds of years. Oral contracts most certainly exist, and they are certainly enforceable. Many who negotiate commercial contracts often assume that they are not bound unless and until the agreement is reduced to writing and signed by the parties. However, the courts in England are not at all reluctant to find that binding contracts have been made despite the lack of a final writing and signature. Indeed, as we have previously noted, even in the narrow area where written and signed contracts are required (for example pursuant to the Statute of Frauds requirement that contracts for the sale of land must be in writing), the courts can find the requisite writing and signature in an exchange of emails.1 As for oral contracts, a recent informative example is presented by the case of Rowena Williams (as executor of William Batters) v Gregory Jones (25 February 2014) reported on Lawtel reference LTL 7/3/2014 document number AC0140753. -

Chivalry Feudalism • Code of Behavior for Medieval Society

9/13/2008 The Fall of the Roman Empire Periodization • After the “fall” of the Roman Empire there were two distinct “Europes”, Early Middle Ages: 500 – 1000 each with their own characteristics, cultures, and societies. Eastern Europe– flourishing, literate, influenced by both Christianity and Islam Western Europe– experiencing a “dark age.” High Middle Ages: 1000 – 1250 Late Middle Ages: 1250 – 1500 (Renaissance) : 1350-1500 Political System Chivalry Feudalism • Code of behavior for medieval society. –Be brave in battle. Code of Economic – Behavior System Fight fairly. = Medieval –Be loyal. Manors Chivalry Society Manorialism –Defend the Church. –Treat women in a courteous manner. Belief System The Catholic Church Chivalric Code Chivalry: A Code of Honor and Behavior King Arthur and Knights of the Round Table— • Thou shalt believe all that the Church teaches, and shalt observe legend to promote Chivalry all its directions. --Monty Python and Search for the Holy Grail • Thou shalt defend the Church. • Thou shalt love the country in which thou wast born and be loyal to thou Lord. • Thou shalt not recoil before thine enemy. • Thou shalt make war against the Infidel without cessation, and without mercy. • Thou shalt perform scrupulously thy feudal duties, if they be not contrary to the laws of God. • Thou shalt never lie, and shall remain faithful to thy pledged word. • Thou shalt be everywhere and always the champion of the Right and the Good against Injustice and Evil. clip 1 9/13/2008 Medieval Situation Feudalism • The Roman Empire has fallen—overtaken by barbarian tribes Feudalism developed in Europe following the fall of the from the north. -

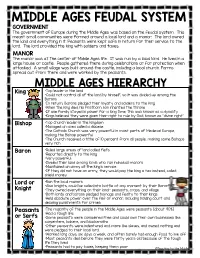

FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT the Government of Europe During the Middle Ages Was Based on the Feudal System

MIDDLE AGES FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT The government of Europe during the Middle Ages was based on the feudal system. This meant small communities were formed around a local lord and a manor. The lord owned the land and everything in it. Peasants were kept safe in return for their service to the lord. The lord provided the king with soldiers and taxes. MANOR The manor was at the center of Middle Ages life. It was run by a local lord. He lived in a large house or castle. People gathered there during celebrations or for protection when attacked. A small village was built around the castle, including a local church. Farms spread out from there and were worked by the peasants. MIDDLE AGES HIERARCHY King *Top leader in the land *Could not control all of the land by himself, so it was divided up among the Barons *In return, Barons pledged their loyalty and soldiers to the king *When the king died, his firstborn son inherited the throne *If one family stayed in power for a long time, this was known as a dynasty *Kings believed they were given their right to rule by God, known as “divine right” Bishop *Top church leader in the kingdom *Managed an area called a diocese *The Catholic Church was very powerful in most parts of Medieval Europe, making the Bishop powerful *The Church received a tithe of 10 percent from all people, making some Bishops very rich Baron *Ruled large areas of land called fiefs *Reported directly to the king *Very powerful *Divided their land among lords who ran individual manors *Maintained an army at the king’s service *If -

Future Interests in Property in Minnesota Everett Rf Aser

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1919 Future Interests in Property in Minnesota Everett rF aser Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Fraser, Everett, "Future Interests in Property in Minnesota" (1919). Minnesota Law Review. 1283. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/1283 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MINNESOTA LAW REVIEW FUTURE INTERESTS IN PROPERTY IN MINNESOTA "ORIGINALLY the creation of future interests at law was greatly restricted, but now, either by the Statutes of Uses and of Wills, or by modern legislation, or by the gradual action of the courts, all restraints on the creation of future interests, except those arising from remoteness, have been done away. This practically reduces the law restricting the creation of future interests to the Rule against Perpetuities,"' Generally in common law jurisdictions today there is but one rule restricting the crea- tion of future interests, and that rule is uniform in its application to real property and to personal property, to legal and equitable interests therein, to interests created by way of trust, and to powers. In 1830 the New York Revised Statutes went into effect in New York state. The revision had been prepared by a commis- sion appointed for the purpose five years before. It contained a code of property law in which "the revisers undertook to re- write the whole law of future estates in land, uses and trusts .. -

Feudalism & Medieval Life

Feudalism & Medieval Life The Feudal System was introduced to England following the invasion and conquest of the island by William the Conqueror. The Feudal System had been used in France by the Normans from the time they first settled there around 900 AD. It was a simple, but effective system for the control of society by the King. All land was owned by the King, and one quarter was kept by as his personal property. Some land was given to the Catholic Church and the rest was leased out to others under strict controls. This means that others paid the king to use the land since he owned it. Land given to others was known as a fief. The King was in complete control under the Feudal System. He owned all the land in the country and decided who he would grant a fief to. He therefore only allowed those men he could trust to lease land from him. However, before they were given any land they had to swear an oath to remain faithful to the King. This was done at a formal and symbolic ceremony which was composed of the two-part act of loyalty and oath of fealty. The man receiving the fief then became a vassal of the king. Vassals who leased land from the King were sometimes known as Barons and were generally wealthy and powerful. The fiefs that Barons were granted by the King were governed by the manor system. The vassal was known as the Lord of the Manor and established his own system of justice, minted money and set up taxes.