Notes on the Lancaster Estates in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Luttrellstown Demesne, Co. Dublin

NORTHERN IRELAND HERITAGE GARDENS TRUST OCCASIONAL PAPER, No 4 (2015) 'Without Rival in our Metropolitan County' - The History of Luttrellstown Demesne, Co. Dublin Terence Reeves-Smyth Luttrellstown demesne, which occupies around 600 acres within its walls, has long been recognised as the finest eighteenth century landscape in County Dublin and one of the best in Ireland. Except for the unfortunate incorporation of a golf course into the eastern portion of its historic parkland, the designed landscape has otherwise survived largely unchanged for over two centuries. With its subtle inter-relationship of tree belts and woodlands, its open spaces and disbursement of individual tree specimens, together with its expansive lake, diverse buildings and its tree-clad glen, the demesne, known as 'Woodlands' in the 19th century, was long the subject of lavish praise and admiration from tourists and travellers. As a writer in the Irish Penny Journal remarked in October 1840: ‘considered in connection with its beautiful demesne, [Luttrellstown] may justly rank as the finest aristocratic residence in the immediate vicinity of our metropolis.. in its natural beauties, the richness of its plantations and other artificial improvements, is without rival in our metropolitan county, and indeed is characterised by some features of such exquisite beauty as are rarely found in park scenery anywhere, and which are nowhere to be surpassed’.1 Fig 1. 'View on approaching Luttrellstown Park', drawn & aquatinted by Jonathan Fisher; published as plate 6 in Scenery -

Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History

SOME NOTES ON MANORS & MANORIAL HISTORY BY A. HAMILTON THOMPSON, M.A.. D.Litt.. F.B.A..F.S.A. Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History By A. Hamilton Thompson, M.A., D.Litt., F.B.A., F.S.A. The popular idea of a manor assumes that it is a fixed geo graphical area with definite boundaries, which belongs to a lord with certain rights over his tenants. In common usage, we speak of this or that lordship, almost in the same way in which we refer to a parish. It is very difficult, however, to give the word an exclusively geographical meaning. If we examine one of those documents which are known as Inquisitions post mortem, for example, we shall find that, at the death of a tenant who holds his property directly from the Crown, the king's escheator will make an extent, that is, a detailed valuation, of his manors. This will consist for the most part of a list of a number of holdings with names of the tenants, specifying the rent or other services due to the lord from each. These holdings will, it is true, be generally gathered together in one or more vills or townships, of which the manor may roughly be said to consist. But it will often be found that there are outlying holdings in other vills which owe service to a manor, the nucleus of which is at some distance. Thus the members of the manor of Rothley lay scattered at various distances from their centre, divided from it and from each other by other lordships. -

The Early History of Man's Activities in the Quernmore Area

I Contrebis 2000 The Early History of Man's Activities in the Quernmore Area. Phil Hudson Introduction This paper hopes to provide a chronological outline of the events which were important in creating the landscape changes in the Quernmore forest area. There was movement into the area by prehistoric man and some further incursions in the Anglo- Saxon and the Norse periods leading to Saxon estates and settled agricultural villages by the time of the Norman Conquest. These villages and estates were taken over by the Normans, and were held of the King, as recorded in Domesday. The Post-Nonnan conquest new lessees made some dramatic changes and later emparked, assarted and enclosed several areas of the forest. This resulted in small estates, farms and vaccaries being founded over the next four hundred years until these enclosed areas were sold off by the Crown putting them into private hands. Finally there was total enclosure of the remaining commons by the 1817 Award. The area around Lancaster and Quernmore appears to have been occupied by man for several thousand years, and there is evidence in the forest landscape of prehistoric and Romano-British occupation sites. These can be seen as relict features and have been mapped as part of my on-going study of the area. (see Maps 1 & 2). Some of this field evidence can be supported by archaeological excavation work, recorded sites and artif.act finds. For prehistoric occupation in the district random finds include: mesolithic flints,l polished stone itxe heads at Heysham;'worked flints at Galgate (SD 4827 5526), Catshaw and Haythomthwaite; stone axe and hammer heads found in Quernmore during the construction of the Thirlmere pipeline c1890;3 a Neolithic bowl, Mortlake type, found in Lancaster,o a Bronze Age boat burial,s at SD 5423 5735: similar date fragments of cinerary urn on Lancaster Moor,6 and several others discovered in Lancaster during building works c1840-1900.7 Several Romano-British sites have been mapped along with finds of rotary quems from the same period and associated artifacts. -

Report and Accounts Year Ended 31St March 2016

Report and Accounts Year ended 31st March 2016 Preserving the past, investing for the future annual report to 31st March 2016 Annual Report Report and accounts of the Duchy of Lancaster for the year ended 31 March 2016 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 2 of the Duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall (Accounts) Act 1838. annual report to 31st March 2016 River Hodder, Whitewell Estate, Lancashire. annual report to 31st March 2016 Introduction The Duchy of Lancaster is a private History estate owned by Her Majesty The In 1265, King Henry III gifted to his Queen as Duke of Lancaster. It has son Edmund the baronial lands of been the personal estate of the Simon de Montfort. A year later, he reigning Monarch since Henry IV in added the estate of Robert Ferrers, 1399 and is held separately to all other Earl of Derby and then the ‘honor, Crown possessions. county, town and castle of Lancaster’, giving Edmund the new title of Earl of The ancient inheritance began over Lancaster. 750 years ago. Historically, its growth was achieved via legacy, alliance In 1267, Edmund also received from his and appropriation. In more modern father the manor of Newcastle-under- times, growth has been delivered Lyme in Staffordshire, together with through active asset management. lands and estates in both Yorkshire and Lancashire. This substantial Her Majesty The Queen, Today, the estate covers 18,542 inheritance was further added to Duke of Lancaster. hectares of rural land divided into by Edmund’s mother, Eleanor of five Surveys: Cheshire, Lancashire, Provence, who bestowed on him the Southern, Staffordshire and Yorkshire. -

Feudalism Manors

effectively defend their lands from invasion. As a result, people no longer looked to a central ruler for security. Instead, many turned to local rulers who had their Recognizing own armies. Any leader who could fight the invaders gained followers and politi- Effects cal strength. What was the impact of Viking, Magyar, and A New Social Order: Feudalism Muslim invasions In 911, two former enemies faced each other in a peace ceremony. Rollo was the on medieval head of a Viking army. Rollo and his men had been plundering the rich Seine (sayn) Europe? River valley for years. Charles the Simple was the king of France but held little power. Charles granted the Viking leader a huge piece of French territory. It became known as Northmen’s land, or Normandy. In return, Rollo swore a pledge of loyalty to the king. Feudalism Structures Society The worst years of the invaders’ attacks spanned roughly 850 to 950. During this time, rulers and warriors like Charles and Rollo made similar agreements in many parts of Europe. The system of governing and landhold- ing, called feudalism, had emerged in Europe. A similar feudal system existed in China under the Zhou Dynasty, which ruled from around the 11th century B.C.until 256 B.C.Feudalism in Japan began in A.D.1192 and ended in the 19th century. The feudal system was based on rights and obligations. In exchange for military protection and other services, a lord, or landowner, granted land called a fief.The person receiving a fief was called a vassal. -

B. Medieval Manorialism and Peasant Serfdom: the Agricultural Foundations of Medieval Feudalism Revised 21 October 2013

III. BARRIERS TO ECONOMIC GROWTH IN THE MEDIEVAL ECONOMY: B. Medieval Manorialism and Peasant Serfdom: the Agricultural Foundations of Medieval Feudalism revised 21 October 2013 Manorialism: definitions • (1) a system of dependent peasant cultivation, • in which a community of peasants, ranging from servile to free, received their lands or holdings from a landlord • - usually a feudal, military lord • (2) the peasants: worked those lands at least in part for the lord’s economic benefit • - in return for both economic and military security in holding their tenancy lands from that military lord. Medieval Manorialism Key Features • (1) European manorialism --- also known as seigniorialism [seignior, seigneur = lord] both predated and outlived feudalism: predominant agrarian socio-economic institution from 4th-18th century • (2) Medieval manorialism: links to Feudalism • The manor was generally a feudal fief • i.e., a landed estate held by a military lord in payment and reward for military services • Feudal fiefs were often collections of manors, • servile peasants provided most of labour force in most northern medieval manors (before 14th century) THE FEUDAL LORD OF THE MANOR • (1) The Feudal Lord of the Manor: almost always possessed judicial powers • secular lord: usually a feudal knight (or superior lord: i.e., count or early, duke, etc.); • ecclesiastical lord: a bishop (cathedral); abbot (monastery); an abbess (nunnery) • (2) Subsequent Changes: 15th – 18th centuries • Many manors, in western Europe, passed into the hands of non-feudal -

Matlock Bath. Walter M

MATLOCK, MAT·LOCK BATH,AND BORDERS. Reduced from the Ordnance Survey. ~~ • ,---.. ! TIN Rn,11 \ • • • ............ ............. ...... ,,, •, . .. ...a:-.. , Btac/cbrook " . ..... ... Koor ~r:P ............ ~ / ..t:.4.:lt *-'=4 . e...:. .,.... , .._.JA. • "' ... ...... * ........... -.. it ........ ' ~... a./• .. ...........u ~----.. / . .. ... ... ..._ ... ~· . • .,,,p_--... o'·~:. ...... u, .., ........ ..-: <-. ,~ 4. ..... .. ........ ,. ia••=-•·=;-., ..~"=::: >.• •/.-.;; ·- ................ ,, :t. .t. 4 ''',). ~lliddle .lloor . ·. .,, . ~ e'a . .. ......... a. 0 fl) e 0 • r 0 r :II ............ *., ,---. ....~.,.'!' :. .......... ~ ........... dnope Q.arriu ............. • 905 Far leg • ..--·-- · __... ...____";MATLOC :I ............ ....... ,,. .. ..... ., .•. \ \ \ - ..... ,1,,.,, -~\ . i i I .·u, •." ·; ... ".·-.,-· .• if :~:'.~.. _B-::o w ·0·••;=;1•:. • -- 4 ~ .......,._ ~~ ~ ~,o.:<Q. :.: ~- .. '°~. .:""'{lie.,_ -~ "'o \\_'.icke,- • o :Tor 0 ~ • G, '-~- 4A. ., A. :-·•••• ,: • ,. ~-~u ,o;~.,; -.....::.-,,.,... ..!~.a.O•~. , 4 ~ A~-...~~:,: 0 '°".•, -A. 9,,-•..,s."' ❖... ~o .Q. ,.,_== 4"" • •" ····... _o • • - ,':r.o. :.=· 4.. :: 4 4(;~t~:·;if -~"'' 9 • -• ·: :.:- Q. =~ \!~.~-<>: t 9.'~ ·: Q, ~j;;• .; ~-'il!9t;~• .....-~ q .. 4.,: ...,. Reproduced from -the Ordnance Survey Map with the .sanction of'-tJ,e C,ontro!Jer of H.Ms. St:Jtionery Office. StanfortI:s Geog !-Eatall:..loruiPv 0t:==========='=====:::l:====;l::::::==========l:::====:::i===~ 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 ci'AJNS MATLOCK MANOR AND p ARI SH Historical ~ 'Descriptive WITH -

Report and Accounts Year Ended 31St March 2019

Report and Accounts Year ended 31st March 2019 Preserving the past, investing for the future LLancaster Castle’s John O’Gaunt gate. annual report to 31st March 2019 Annual Report Report and accounts of the Duchy of Lancaster for the year ended 31 March 2019 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 2 of the Duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall (Accounts) Act 1838. annual report to 31st March 2019 Introduction Introduction History The Duchy of Lancaster is a private In 1265, King Henry III gifted to his estate in England and Wales second son Edmund (younger owned by Her Majesty The Queen brother of the future Edward I) as Duke of Lancaster. It has been the baronial lands of Simon de the personal estate of the reigning Montfort. A year later, he added Monarch since 1399 and is held the estate of Robert Ferrers, Earl separately from all other Crown of Derby and then the ‘honor, possessions. county, town and castle of Lancaster’, giving Edmund the new This ancient inheritance began title of Earl of Lancaster. over 750 years ago. Historically, Her Majesty The Queen, Duke of its growth was achieved via In 1267, Edmund also received Lancaster. legacy, alliance and forfeiture. In from his father the manor of more modern times, growth and Newcastle-under-Lyme in diversification have been delivered Staffordshire, together with lands through active asset management. and estates in both Yorkshire and Lancashire. This substantial Today, the estate covers 18,481 inheritance was further enhanced hectares of rural land divided into by Edmund’s mother, Eleanor of five Surveys: Cheshire, Lancashire, Provence, who bestowed on him Staffordshire, Southern and the manor of the Savoy in 1284. -

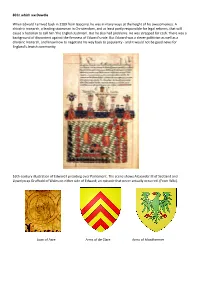

80 in Which We Dawdle When Edward I Arrived Back in 1289 from Gascony, He Was in Many Ways at the Height of His Awesomeness

80 In which we Dawdle When Edward I arrived back in 1289 from Gascony, he was in many ways at the height of his awesomeness. A chivalric monarch, a leading statesman in Christendom, and at least partly responsible for legal reforms, that will cause a historian to call him 'the English Justinian'. But he also had problems. He was strapped for cash. There was a background of discontent against the firmness of Edward's rule. But Edward was a clever politician as well as a chivalric monarch, and knew how to negotiate his way back to popularity - and it would not be good news for England's Jewish community. 16th-century illustration of Edward I presiding over Parliament. The scene shows Alexander III of Scotland and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Wales on either side of Edward; an episode that never actually occurred. (From Wiki). Joan of Acre Arms of de Clare Arms of Monthermer Northampton Charing Cross Geddington Plaque at Northampton Eleanor of Castile 81 The Great Cause Through a stunning piece of bad luck, Alexander III left no heirs. And now there was no clear successor to his throne of Scotland. For the search for the right successor, the Scottish Guardians of the Realm turned to Scotland's friend - England. But Edward had other plans - for him this was a great opportunity to revive the claims of the kings of England to be overlords of all Britain. The Maid of Norway Coronation Chair and Stone of Scone Stain Glass window Lerwick Town Hall King Edward's Chair today sans the Stone of Destiny. -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

The Red Rose of Lancaster? JOHN ASHDOWN—HILL In the fifteenth century the rival houses of Lancaster and York fought the ‘Wars of the Roses’ for possession of the crown. When, in 1485, the new Tudor monarch, Henry VII, brought these wars to an end, he united, by his mam'age to Elizabeth of York, the red rose of Lancaster and the white rose of York, to create a new emblem and a new dynasty. Thus was born the Tudor rose. So might run a popular account, and botanists, searching through the lists of medieval rose cultivars, have even proposed identifications of the red rose of Lancaster with Rosa Gallica and the white rose of York with Rosa Alba, while the bi-coloured Tudor rose is linked to the naturally occurring variegated sport of Rosa Gallica known as ‘Rosa Mundi’ (Rosa Gallica versicolor), or alternatively, to the rather paler Rosa Damascena versicolor. It should, perhaps, be observed that Rosa Gallica, while somewhat variable in colour. is more likely to be a shade of pink than bright red, and Rosa Alba, while generally white in colour, also occurs in shades of pink, so that in nature the colour~distinction between the two roses is not always clear. ‘Rosa Mundi’ is also strictly speaking variegated in two shades of pink, rather than being literally red and white.‘ The label ‘Wars of the Roses’was a late invention, first employed only in 1829, by Sir Walter Scott, in his romantic novel Anne of Geierstein.2 The story of the rose emblems might appear on casual inspection to be well-founded, for we find ample evidence of Tudor roses bespattering Tudor coinage and royal architecture, for example, at Hampton Court, the Henry VII chapel at Westminster, and at Cambridge, on the gates of Christ’s and St John’s Colleges, and in King’s College chapel. -

The Livery Collar: Politics and Identity in Fifteenth-Century England

The Livery Collar: Politics and Identity in Fifteenth-Century England MATTHEW WARD, SA (Hons), MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy AUGUST 2013 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, lS23 7BQ www.bl.uk ANY MAPS, PAGES, TABLES, FIGURES, GRAPHS OR PHOTOGRAPHS, MISSING FROM THIS DIGITAL COPY, HAVE BEEN EXCLUDED AT THE REQUEST OF THE UNIVERSITY Abstract This study examines the social, cultural and political significance and utility of the livery collar during the fifteenth century, in particular 1450 to 1500, the period associated with the Wars of the Roses in England. References to the item abound in government records, in contemporary chronicles and gentry correspondence, in illuminated manuscripts and, not least, on church monuments. From the fifteenth century the collar was regarded as a potent symbol of royal power and dignity, the artefact associating the recipient with the king. The thesis argues that the collar was a significant aspect of late-medieval visual and material culture, and played a significant function in the construction and articulation of political and other group identities during the period. The thesis seeks to draw out the nuances involved in this process. It explores the not infrequently juxtaposed motives which lay behind the king distributing livery collars, and the motives behind recipients choosing to depict them on their church monuments, and proposes that its interpretation as a symbol of political or dynastic conviction should be re-appraised. After addressing the principal functions and meanings bestowed on the collar, the thesis moves on to examine the item in its various political contexts. -

The Crouchbank Legend Revisted T.P.J

The Crouchbank Legend Revisted T.P.J. EDLIN With great interest I read John Ashdown-Hill’s stimulating article on the Lancastrian claim to the throne and Henry IV’s use of his descent from Edmund Crouchback, Earl of Lancaster and younger son of Henry III, to formulate a claim to the throne based on the legend that Edmund had in fact been the elder brother of Edward I. This brought to mind several additional thoughts which are set out here in the manner of an augmentation rather than a refutation. First, I discuss recent work which has advanced the claims of John Hardyng’s Chronicle as a source for the background to Henry IV’s usurpation and his use of the ‘Crouchback legend’, and which suggests that there was a systematic and ambitious plan to hijack chronicle evidence in Henry’s favour — a plan which failed, but may ultimately have helped to perpetuate a stubborn if ill-defined remnant of the Crouchback myth. Secondly, the poem Richard the Redeless will be considered, and the possibility that its guardedly Lancastrian perspective hints at the general currency of ideas about Henry’s legitimacy — and, at the same time, Richard II’s illegitimacy — as king. There are, in conclusion, some further thoughts on the differing interpretations of the meaning of Henry’s claim that he was taking the throne as the legitimate heir, ‘of the right line of the blood’ in descent from Henry III. It seems to me that the ‘contemporary tradition that ([Henry III’s son) Edmund was born before his brother Edward’ cited by John Ashdown-Hill refers to the life-time of John of Gaunt.2 Such a promotion (or even invention) of every possible (or impossible) right or claim within Gaunt’s immediate family was entirely consistent with his character and career.