Language Practices of Indigenous Children and Youth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Than One Way to Catch a Frog: a Study of Children's

More than one way to catch a frog: A study of children’s discourse in an Australian contact language Samantha Disbray Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Linguistics and Applied Linguistics University of Melbourne December, 2008 Declaration This is to certify that: a. this thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD b. due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all material used c. the text is less than 100,000 words, exclusive of tables, figures, maps, examples, appendices and bibliography ____________________________ Samantha Disbray Abstract Children everywhere learn to tell stories. One important aspect of story telling is the way characters are introduced and then moved through the story. Telling a story to a naïve listener places varied demands on a speaker. As the story plot develops, the speaker must set and re-set these parameters for referring to characters, as well as the temporal and spatial parameters of the story. To these cognitive and linguistic tasks is the added social and pragmatic task of monitoring the knowledge and attention states of their listener. The speaker must ensure that the listener can identify the characters, and so must anticipate their listener’s knowledge and on-going mental image of the story. How speakers do this depends on cultural conventions and on the resources of the language(s) they speak. For the child speaker the development narrative competence involves an integration, on-line, of a number of skills, some of which are not fully established until the later childhood years. -

Endangered Songs and Endangered Languages

Endangered Songs and Endangered Languages Allan Marett and Linda Barwick Music department, University of Sydney NSW 2006 Australia [[email protected], [email protected]] Abstract Without immediate action many Indigenous music and dance traditions are in danger of extinction with It is widely reported in Australia and elsewhere that songs are potentially destructive consequences for the fabric of considered by culture bearers to be the “crown jewels” of Indigenous society and culture. endangered cultural heritages whose knowledge systems have hitherto been maintained without the aid of writing. It is precisely these specialised repertoires of our intangible The recording and documenting of the remaining cultural heritage that are most endangered, even in a traditions is a matter of the highest priority both for comparatively healthy language. Only the older members of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Many of the community tend to have full command of the poetics of our foremost composers and singers have already song, even in cases where the language continues to be spoken passed away leaving little or no record. (Garma by younger people. Taking a number of case studies from Statement on Indigenous Music and Performance Australian repertories of public song (wangga, yawulyu, 2002) lirrga, and junba), we explore some of the characteristics of song language and the need to extend language documentation To close the Garma Symposium, Mandawuy Yunupingu to include musical and other dimensions of song and Witiyana Marika performed, without further performances. Productive engagements between researchers, comment, two djatpangarri songs—"Gapu" (a song performers and communities in documenting songs can lead to about the tide) and "Cora" (a song about an eponymous revitalisation of interest and their renewed circulation in contemporary media and contexts. -

How Understanding the Aboriginal Kinship System Can Inform Better

How understanding the Aboriginal Kinship system can inform better policy and practice: social work research with the Larrakia and Warumungu Peoples of the Northern Territory Submitted by KAREN CHRISTINE KING BSW A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Social Work Faculty of Arts and Science Australian Catholic University December 2011 2 STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person‟s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the Australian Catholic University Human Research Ethics Committee. Karen Christine King BSW 9th March 2012 3 4 ABSTRACT This qualitative inquiry explored the kinship system of both the Larrakia and Warumungu peoples of the Northern Territory with the aim of informing social work theory and practice in Australia. It also aimed to return information to the knowledge holders for the purposes of strengthening Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing. This study is presented as a journey, with the oral story-telling traditions of the Larrakia and Warumungu embedded and laced throughout. The kinship system is unpacked in detail, and knowledge holders explain its benefits in their lives along with their support for sharing this knowledge with social workers. -

14 Annu a L Repo

20 t R l Repo A 14 Annu The Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language is an ARC funded centre of excellence (CE140100041). College of Asia and the Pacifc The Australian National Unviersity H.C. Coombs Building Fellows Road, Acton ACT 2601 Email: [email protected] Phone: (02) 6125 9376 www.dynamicsofanguage.edu.au www.facebook.com/CoEDL © ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language 2014 Design: Sculpt Communications ARC Centre of excellence for the Dynamics of language Annual Report 2014 table of contents Section 1: The Centre 7 Section 2: People 25 Section 3: Research 49 Section 4: Education, Training and Mentoring 75 Section 5: Outreach and Engagement 81 Section 6: Outputs 90 Section 7: Financials 103 Section 8: Performance indicators 105 7 one on I t C e S 01tHe CentRe HEADING HEADING Introducing the ARC Centre of excellence for the Dynamics of language 8 Using language is as natural as breathing, and almost as important, for using language transforms every aspect of human experience. But it has been extraordinarily diffcult to understand its evolution, diversifcation, and use: a vast array of incredibly different language systems are found across the planet, all representing different solutions to the problem of evolving a fexible, all-purpose communication system, and all in constant fux. The ARC Centre of Excellence for the To achieve this transformation of the Dynamics of Language (CoEDL) will shift language sciences and the fow-on the focus of the language sciences from the translational outcomes for the public and long-held dominant view that language is a end-users, we have assembled a team which static and genetically constrained system — makes surprising and bold connections to a dynamic model where diversity, variation, between areas of research that until now plasticity and evolution, along with complex have not been connected: linguistics, interactions between language-learning and speech pathology, psychology, anthropology, perceptual and cognitive processes, lie at the philosophy, bioinformatics and robotics. -

Commonwealth of Australia

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of The Charles Darwin University with permission from the author(s). Any further reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander THESAURUS First edition by Heather Moorcroft and Alana Garwood 1996 Acknowledgements ATSILIRN conference delegates for the 1st and 2nd conferences. Alex Byrne, Melissa Jackson, Helen Flanders, Ronald Briggs, Julie Day, Angela Sloan, Cathy Frankland, Andrew Wilson, Loris Williams, Alan Barnes, Jeremy Hodes, Nancy Sailor, Sandra Henderson, Lenore Kennedy, Vera Dunn, Julia Trainor, Rob Curry, Martin Flynn, Dave Thomas, Geraldine Triffitt, Bill Perrett, Michael Christie, Robyn Williams, Sue Stanton, Terry Kessaris, Fay Corbett, Felicity Williams, Michael Cooke, Ely White, Ken Stagg, Pat Torres, Gloria Munkford, Marcia Langton, Joanna Sassoon, Michael Loos, Meryl Cracknell, Maggie Travers, Jacklyn Miller, Andrea McKey, Lynn Shirley, Xalid Abd-ul-Wahid, Pat Brady, Sau Foster, Barbara Lewancamp, Geoff Shepardson, Colleen Pyne, Giles Martin, Herbert Compton Preface Over the past months I have received many queries like "When will the thesaurus be available", or "When can I use it". Well here it is. At last the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Thesaurus, is ready. However, although this edition is ready, I foresee that there will be a need for another and another, because language is fluid and will change over time. As one of the compilers of the thesaurus I am glad it is finally completed and available for use. -

A PDF Combined with Pdfmergex

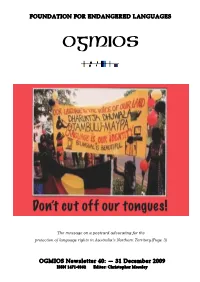

!"#$%&'("$)!"*)+$%&$,+*+%)-&$,#&,+.) ) OGMIOS The message on a postcard advocating for the protection of language rights in Australia’s Northern Territory (Page 3) ",/(".)$012304405)678)9):;)%0<0=>05)?77@) (..$);6A;B7:C?))))))+DE4F58)GH5E24FIH05)/F2030J) 2 DEBFD<'C4G"64$$4+'HI,'J'KL'=4/4M14+'NIIO' F<<C'LHPLQIKRN''''''()#$*+,'07+#"$*:74+'B*"464;' !""#"$%&$'()#$*+,'!)+#%&*'-+."/*$$' 0*&$+#1.$#&2'()#$*+",'3*24+'564&/78'9*"4:7'56;$748'<4+4&%'=>!2*"$#&*8'07+#"$*:74+'?%)@#46)8'A+%&/#"'B'?.6$8'' C#/7*6%"'D"$64+8'!&)+4%'3#$$4+' ' !"#$%&$'$()'*+,$"-'%$.' /012,3()+'14.' ' 07+#"$*:74+'B*"464;8' A*.&)%$#*&'@*+'(&)%&24+4)'X%&2.%24"8' O'S4"$)4&4'0+4"/4&$8' LPN'5%#61+**Y'X%&48'' 0%T4+"7%M'?4#27$"8' 5%$7'5!L'P!!8'(&26%&)' 34%)#&2'3EH'P?=8'(&26%&)' &*"$64+V/7#1/7%W)4M*&W/*W.Y'' /7+#"M*"464;UIV;%7**W/*M'' 'GGGW*2M#*"W*+2' The Austronesian Languages......................................... 19! LW'()#$*+#%6 3! Immersion – a film on endangered languages ............... 19! Cover Story: Northern Territory’s small languages sidelined from schools ...................................................... 3! RW'\6%/4"'$*'2*'*&'$74'S41 20! NW! =4T46*:M4&$'*@'$74'A*.&)%$#*& 4! Irish upside down............................................................ 20! Resolution of the FEL XIII Conference, Khorog, Tajikistan, OW'A*+$7/*M#&2'4T4&$" 21! 26, September, 2009 ........................................................ 4! HRELP Workshop: Endangered Languages, endangered FEL and UNESCO Atlas partnership................................ 4! knowledge & sustainability............................................. -

Aboriginal Business

Aboriginal Business Alliance-Making 1 An Introduction The second Australian Tribal-class destroyer warship, the HMAS Warramunga, was commissioned in 1942 and almost immediately saw duty supporting American troops in the New Guinea campaign.1 With the Japanese at Australia’s doorstep, there was no time to generate an official badge for the Warramunga. Early in 1943 Captain Dechaineux, recognizing the oversight, organized a competition on board. Petty Officer Hugh Anderson and Able Seaman Arthur Paul collaborated on a design and motto emphasizing the character of the Warramunga. A tall Aboriginal man wielding a boomerang encapsulated the seamen’s fierceness, while the phrase “Courage in Difficul- ties” summarized the young nation’s wartime attitude. The badge, however, had no official standing and was removed two years later. From 1946 to 1955 the ship once again sailed without a badge. Then, in 1956, Commander Purvis officially proposed, and had approved, a head-and-shoulder image of an Aboriginal man, this time wielding a spear with the caption “Hunt and Harass.” For the next three years the Warramunga sailed under this badge and motto. The warship was finally decommissioned in 1959 and sold for scrap metal to the Japanese in 1963. In 1987 a group of naval veterans who had served on the Warramunga during World War II successfully lobbied the chief of navy to ensure the original badge would be used should the vessel ever be recommissioned. It was. On May 23, 1998, the HMAS Warramunga II was launched with the original 1943 badge and motto. Several Warumungu men and women from Tennant Creek were present at the ceremony in Melbourne and performed COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL 888-390-6070 1 traditional dances prior to the ceremony. -

The Songline Is Alive in Mukurtu”: Return, Reuse, and Respect

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 18 Archival returns: Central Australia and beyond ed. by Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green & Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, pp. 153–172 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp18 8 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24882 “The songline is alive in Mukurtu”: Return, reuse, and respect Kimberly Christen Washington State University Abstract This chapter examines the return, reuse, and repositioning of archival materials within Indigenous communities and specifically within the Warumungu Aboriginal community in Central Australia. Over the last 20 years there has been an uptake in collecting institutions and scholars returning cultural, linguistic, and historical material to Indigenous communities in digital formats. These practices of digital return have been spurred by decolonisation and reconciliation movements globally, and at the same time catalysed by new technologies that allow for surrogates to be returned and concurrently reinvented, reused, and reimagined in community, kin-based, and place-based social and cultural networks. Examining the creation, use, and ongoing development of Mukurtu CMS, this article focuses on the implications for digital return as a type of repatriation that promotes decolonising strategies and reparative frameworks for engagement. Keywords: digital return, archival studies, repatriation, digital archives, Warumungu Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International 154 Kimberly Christen Opening1 In May of 2017 I sat with several Warumungu and Warlmanpa women in the Cultural Resource Room at the Nyinkka Nyunyu Art and Culture Centre in Tennant Creek, Northern Territory (NT), Australia, listening over and over again to Milwayi and Mungamunga songs recorded by researchers over several decades. The women were from several family groups in the Barkly region, related through these songlines. -

Guide to Sound Recordings Collected by Jeffrey Heath, 1976-1977

Finding aid HEATH_J05 Sound recordings collected by Jeffrey Heath, 1976-1977 Prepared November 2011 by CC Last updated 12 December 2011 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening This collection is open for listening. Restrictions on use Copies of this collection may be made for private research. Permission must be sought from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1976-1977 Extent: 12 sound cassettes (ca. 60 min. each) : analogue, mono. Production history These recordings were collected at Numbulwar, Rose River and Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory of Australia by linguist and AIAS (now AIATSIS) Research Fellow Jeffrey Heath during field work between October 1976 and July 1977. The purpose of the field trips was to document the languages, histories and stories in the Numbulwar and Tennant Creek regions. They include Anindilyakwa, Nunggubuyu, Mara and Djambarrpuyngu languages in the Numbulwar region and Warumungu at Tennant Creek. Interviewees include Narlaginya (Grass), Mac Riley, Yurrumurra, Miyala, Homer, Jack Gidjigari, Sandy, Bill Fitz, Albert Murphy (Gurrpanyana), and Ned Haskins. The collection was deposited with AIATSIS 18 August 1977. RELATED MATERIAL Important: before you click on any links in this section, please read our sensitivity message. Transcripts, translations and grammatical notes are held in the AIATSIS library, see MS 2748 and PMS 3802. -

Pair Interactions and Mode of Communication Comparing Face-To-Face and Computer Mediated Communication

ARTICLES PAIR INTERACTIONS AND MODE OF COMMUNICATION COMPARING FACE-TO-FACE AND COMPUTER MEDIATED COMMUNICATION Lan Liana Tan, University of Melbourne Liana Tan is completing her PhD in Applied Linguistics. Her areas of research in- terest are computer mediated communication and how technology can be harnessed to improve the teaching of Chinese. Gillian Wigglesworth, University of Melbourne Gillian Wigglesworth is Professor in Linguistics and Applied Linguistics in the School of Languages and Linguistics at the University of Melbourne. She is teaching in the Master of Applied Linguistics program. Her research covers a range of topics including second language acquisition, language assessment, bilingualism and first language acquisition. Her current research direction is the acquisition of language at home and school by Indigenous children in remote communities in Australia. Neomy Storch, University of Melbourne Neomy Storch is a senior lecturer in Applied Linguistics in the School of Languages and Linguistics, the University of Melbourne. She teaches a range of ESL and Ap- plied Linguistics subjects. Her research has focused on issues related to second language pedagogy. These include the nature of pair interaction in classroom con- texts and the development of academic writing skills, particularly grammatical ac- curacy, and the role of feedback in that development. In today’s second language classrooms, students are often asked to work in pairs or small groups. Such collaboration can take place face-to-face, but now more often via computer mediated communication. This paper reports on a study which investigated the effect of the medium of communication on the nature of pair interaction. The study involved six pairs of beginner parti- cipants in a Chinese class completing seven different tasks. -

Arthur Capell Papers MS 4577 Finding Aid Prepared by J.E

Arthur Capell papers MS 4577 Finding aid prepared by J.E. Churches, additional material added by C. Zdanowicz This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit May 04, 2016 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library March 2010 1 Lawson Crescent Acton Peninsula Acton Canberra, ACT, 2600 +61 2 6246 1111 [email protected] Arthur Capell papers MS 4577 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................. 4 Biographical note ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Scope and Contents note ............................................................................................................................... 6 Arrangement note .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Administrative Information ......................................................................................................................... 8 Related Materials ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Controlled Access Headings ......................................................................................................................... 9 Physical Characteristics -

1 the Languages of Australia in Linguistic Research: Context and Issues

Harold Koch and Rachel Nordlinger 1 The languages of Australia in linguistic research: context and issues 1 Background on the Indigenous languages of Australia At the time of colonisation in the late 18th century, Australia was home to 700–800 language varieties, distributed across the continent (and including Tasmania and the Torres Strait Islands), which can be grouped into more than 250 distinct languages, some of which include a number of dialects.¹,² These language varieties were spoken across a population of around one million people (e.g. Butlin 1983), which indicates the enormous linguistic diversity of Indigenous Australia. In many cases small popu- lations (e.g. 40–50 people) maintained distinctive language varieties, and the largest populations speaking a single language variety were probably no bigger than 3000– 4000 people. Linguistic diversity was not necessarily an impediment to communica- tion, however, since Indigenous societies were frequently highly multilingual, with an individual oft en speaking up to 4–6 languages of the surrounding area. Linguistic diversity, in fact, was valued for its indexical relationship to identity and group mem- bership (Evans 2007). The relationship between language and identity is strong for all human societies, but is particularly so in Indigenous Australia, where language is oft en related directly to the land. As Rumsey (1993, 2005) explains, in Australia there is a direct relationship between a language and a tract of land; in creation myths it is very common for the ancestors to be described as passing across the land instilling diff erent languages into diff erent areas as they go (Evans 2007: 20).