Capitalism and Immigration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Speaker of the House of Commons: the Office and Its Holders Since 1945

The Speaker of the House of Commons: The Office and Its Holders since 1945 Matthew William Laban Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 1 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I, Matthew William Laban, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of this thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: Details of collaboration and publications: Laban, Matthew, Mr Speaker: The Office and the Individuals since 1945, (London, 2013). 2 ABSTRACT The post-war period has witnessed the Speakership of the House of Commons evolving from an important internal parliamentary office into one of the most recognised public roles in British political life. This historic office has not, however, been examined in any detail since Philip Laundy’s seminal work entitled The Office of Speaker published in 1964. -

Text Cut Off in the Original 232 6

IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk TEXT CUT OFF IN THE ORIGINAL 232 6 ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE Between 1983 and 1989 there were a series of important changes to Party organisation. Some of these were deliberately pursued, some were more unexpected. All were critical causes, effects and aspects of the transformation. Changes occurred in PLP whipping, Party finance, membership administration, disciplinary procedures, candidate selection, the policy-making process and, most famously, campaign organisation. This chapter makes a number of assertions about this process of organisational change which are original and are inspired by and enhance the search for complexity. It is argued that the organisational aspect of the transformation of the 1980s resulted from multiple causes and the inter-retroaction of those causes rather than from one over-riding cause. In particular, the existing literature has identified organisational reform as originating with a conscious pursuit by the core leadership of greater control over the Party (Heffernan ~\ . !.. ~ and Marqusee 1992: passim~ Shaw 1994: 108). This chapter asserts that while such conscious .... ~.. ,', .. :~. pursuit was one cause, other factors such as ad hoc responses to events .. ,t~~" ~owth of a presidential approach, the use of powers already in existence and the decline of oppositional forces acted as other causes. This emphasis upon multiple causes of change is clearly in keeping with the search for complexity. 233 This chapter also represents the first detailed outline and analysis of centralisation as it related not just to organisational matters but also to the issue of policy-making. In the same vein the chapter is particularly significant because it relates the centralisation of policy-making to policy reform as it occurred between 1983 and 1987 not just in relation to the Policy Review as is the approach of previous analyses. -

Members 1979-2010

Members 1979-2010 RESEARCH PAPER 10/33 28 April 2010 This Research Paper provides a complete list of all Members who have served in the House of Commons since the general election of 1979 to the dissolution of Parliament on 12 April 2010. The Paper also provides basic biographical and parliamentary data. The Library and House of Commons Information Office are frequently asked for such information and this Paper is based on the data we collate from published sources to assist us in responding. This Paper replaces an earlier version, Research Paper 09/31. Oonagh Gay Richard Cracknell Jeremy Hardacre Jean Fessey Recent Research Papers 10/22 Crime and Security Bill: Committee Stage Report 03.03.10 10/23 Third Parties (Rights Against Insurers) Bill [HL] [Bill 79 of 2009-10] 08.03.10 10/24 Local Authorities (Overview and Scrutiny) Bill: Committee Stage Report 08.03.10 10/25 Northern Ireland Assembly Members Bill [HL] [Bill 75 of 2009-10] 09.03.10 10/26 Debt Relief (Developing Countries) Bill: Committee Stage Report 11.03.10 10/27 Unemployment by Constituency, February 2010 17.03.10 10/28 Transport Policy in 2010: a rough guide 19.03.10 10/29 Direct taxes: rates and allowances 2010/11 26.03.10 10/30 Digital Economy Bill [HL] [Bill 89 of 2009-10] 29.03.10 10/31 Economic Indicators, April 2010 06.04.10 10/32 Claimant Count Unemployment in the new (2010) Parliamentary 12.04.10 Constituencies Research Paper 10/33 Contributing Authors: Oonagh Gay, Parliament and Constitution Centre Richard Cracknell, Social and General Statistics Section Jeremy Hardacre, Statistics Resources Unit Jean Fessey, House of Commons Information Office This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. -

GO EAST: UNLOCKING the POTENTIAL of the THAMES ESTUARY Andrew Adonis, Ben Rogers and Sam Sims

GO EAST: UNLOCKING THE POTENTIAL OF THE THAMES ESTUARY Andrew Adonis, Ben Rogers and Sam Sims Published by Centre for London, February 2014 Open Access. Some rights reserved. Centre for London is a politically independent, As the publisher of this work, Centre for London wants to encourage the not-for-profit think tank focused on the big challenges circulation of our work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. facing London. It aims to help London build on its We therefore have an open access policy which enables anyone to access our content online without charge. Anyone can download, save, perform long history as a centre of economic, social, and or distribute this work in any format, including translation, without written intellectual innovation and exchange, and create a permission. This is subject to the terms of the Centre for London licence. fairer, more inclusive and sustainable city. Its interests Its main conditions are: range across economic, environmental, governmental and social issues. · Centre for London and the author(s) are credited Through its research and events, the Centre acts · This summary and the address www.centreforlondon.co.uk are displayed · The text is not altered and is used in full as a critical friend to London’s leaders and policymakers, · The work is not resold promotes a wider understanding of the challenges · A copy of the work or link to its use online is sent to Centre for London. facing London, and develops long-term, rigorous and You are welcome to ask for permission to use this work for purposes other radical solutions for the capital. -

This House Exploring the Play at Home

This House Exploring the Play at Home If you’re watching This House at home and would like to find out more out the production, there are a number of different resources that you can explore. About the Production This production of This House by James Graham was first performed at the National Theatre in 2012. The production was directed by Jeremy Herrin. The play explores life in the corridors of Westminster in 1974. You can find full details of the cast and production team below: Cast Labour Whips Bob Mellish: Phil Daniels Walter Harrison: Reece Dinsdale Michael Cocks/ Joe Harper: Vincent Franklin Ann Taylor: Lauren O’Neil Tory Whips Humphrey Atkins: Julian Wadham Jack Weatherill: Charles Edwards Fred Silvester: Ed Hughes The Members Chorus Clockmaker/Peebles/ Redditch/ Birmingham Perry Barr: Gunnar Cauthery Woolwich West/Batley & Morley/ Western Isles: Christopher Godwin Walsall North/Serjeant at Arms Act I/ Speaker Act II/Plymouth Sutton: Andrew Havill Rochester & Chatham/Welwyn & Hatfield/ Coventry South West/Lady Batley: Helena Lymbery Paddington South/Chelmsford/ South Ayrshire/Henley: Matthew Pidgeon Speaker Act I/Mansfield/ Serjeant at Arms Act II/ West Lothian: Giles Taylor Bromsgrove/Abingdon/ Liverpool Edge Hill/ Paisley/Fermanagh: Tony Turner Esher/Belfast West: Rupert Vansittart All other parts played by members of the Company Musicians Acoustic Jim & The Wires: Jim Hustwit (Music Director/guitar), Sam Edgington (bass) and Cristiano Castellitto (drums). Guest Vocals: Gunnar Cauthery and Phil Daniels Creative Team Director: Jeremy Herrin Designer: Rae Smith Lighting Designer: Paul Anderson Music: Stephen Warbeck Choreographer: Scott Ambler Sound Designer : Ian Dickinson Associate Director: Joe Murphy Original Lighting Designer: Paule Constable Company Voice Work: Richard Ryder Dialect Coach: Penny Dyer You might like to use the internet to research some of these artists to find out more about their careers. -

A Century of Premiers: Salisbury to Blair

A Century of Premiers Salisbury to Blair Dick Leonard A Century of Premiers Also by Dick Leonard THE BACKBENCHER AND PARLIAMENT (ed. with Val Herman) CROSLAND AND NEW LABOUR (ed.) THE ECONOMIST GUIDE TO THE EUROPEAN UNION ELECTIONS IN BRITAIN: A Voter’s Guide (with Roger Mortimore) GUIDE TO THE GENERAL ELECTION PAYING FOR PARTY POLITICS THE PRO-EUROPEAN READER (ed. with Mark Leonard) THE SOCIALIST AGENDA: Crosland’s Legacy (ed. with David Lipsey) WORLD ATLAS OF ELECTIONS (with Richard Natkiel) A Century of Premiers Salisbury to Blair Dick Leonard © Dick Leonard 2005 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2005 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. -

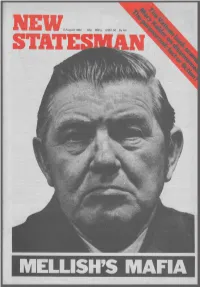

6August 1982

6 August 1982 The- real. mafia man vu lga r-minde dvand very much the he would not seek re-election) the Ber- Bob Mellish ha-sretired from the ", supporter of whoever is his boss at the mondsey Labour Party selected their sesre- Labour Party amid a blaze of . moment'. Mellish was an eager placeman, tary Peter Tatchell as the prospective- can- accusations of 'mafia tactics' and 'hit and has wanted 'desperately to be a Cabinet didate.' Mellish effectively 'blackmailed- Minister responsible for London and for Michael FOQt into. a public repudiation of lists' levelled at the London and housing. His political campaigning -and Tatchell. Although the meeting was secret BermondseyLabour Parties. personal platform has spanned a narrow at the time, the particulars are nQWknown. DUNCAN CAMPBELLreports ON Mt field, from orthodox catholic politics and Mellish threatened that he would resign' Mellish's career. sympathy for the Iberian dictatorships to forthwith if Tatchell were endorsed as can- persistent racialist attitudes-to immigrants didate by the Labour National Executive, HAD HE NOT RESIGNED from the and appeals to free East Enders like and would then campaign against him. Labour Party on Monday, Bob Mellish gangster Charlie Richardson and 'Scarface'. FOQt eventually _agreed to Mellish's de- faced certain expulsion this Friday at the Parsons (a well known robber in the mands leading to. the enormous and hands of West Lewisha:m Labour Party, 1950s). He has been associated; to his em- damaging public row last November. ' where he lives. This was because of his barrassment, .with three corrupt _ busi- Two. -

39-Summer 2003.Indd

For the study of Liberal, SDP and Issue 39 / Summer 2003 / £7.50 Liberal Democrat history Journal of LiberalHI ST O R Y A short history of political virginity Chris Radley, with Mark Pack The story of the SDP Original cartoons from the Social Democrat Bill Rodgers Biography: David Owen Stefan Seelbach Aspects of organisational modernisation The case of the SDP Bill Rodgers and Chris Rennard What went wrong at Darlington? 1983 by-election analysed Conrad Russell, Tom McNally, Tim Benson Book reviews Roy Jenkins, Giles Radice, Alan Mumford Liberal Democrat History Group A SHORT HISTORY OF POLITICAL VIRGINITY he Social Democratic Party Chris Radley, book reviews, and New subscription rates for was launched on 26 March a comprehensive bibliography the Journal T1981, and just under seven and chronology for students of Subscription rates for the Journal years later merged with the the SDP. will be increasing from the new Liberals to form today’s Liberal The original cartoon draw- subscription year, starting in Sep- Democrats. ings themselves – including tember 2003. This is the first rise For most of its existence, the many not reproduced in this for four years; it is necessitated by SDP published a regular news- Journal – will be on display the increasing costs of producing paper, the Social Democrat. One at London’s Gallery 33 (near what is on average a much larger of the paper’s regular cartoonists, London Bridge) throughout publication than hitherto. Chris Radley, has kindly made July 2003. Bill Rodgers, one of An annual subscription to the the originals available for repro- the SDP’s founding ‘Gang of Journal of Liberal History will cost duction in this issue of the Journal Four’, will open the exhibition £15.00 (£7.50 unwaged rate) of Liberal History. -

The Labour Left

THE LABOUR LEFT PATRICK SEYD Ph. D. DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL THEORY AND INSTITUTIONS SUBMITTED JUNE 1986 THE LABOUR LEFT PATRICK SEYD SUMMARY Throughout its lifetime the Labour Party has experienced ideological divisions resulting in the formation of Left and Right factions. The Labour Left has been the more prominent and persistent of the two factions, intent on defending the Party's socialist principles against the more pragmatic leanings of the Party leadership. During the 1930s and 1950s the Labour Left played a significant, yet increasingly reactive, role within the Party. In the 1970s, however, the Labour Left launched an offensive with a wide-ranging political programme, a set of proposals for an intra-Party transferral of power, and a political leader with exceptional skills. By 1981 this offensive had succeeded in securing the election of a Party Leader whose whole career had been very closely identified with the Labour Left, in achieving a significant shift of power from the parliamentarians to the constituency activists, and in developing a Party programme which incorporated certain major left-wing policies. Success, however, contained the seeds of decline. A split in the parliamentary Party and continual bitter intra-Party factional divisions played a major part in the Party's disastrous electoral performance in the 1983 General Election. The election result gave additional impetus to the Labour Left's fragmentation to the point that it is no longer the cohesive faction it was in previous periods and is now a collection of disparate groups. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the Social Science Research Council for its financial aid in the form of a postgraduate research award; Professors Bernard Crick and Royden Harrison for their support and encouragement; and Lewis Minkin for sharing his ideas and encouraging me to complete this project. -

Tony Benn, <I>Against the Tide</I>

Tony Benn, Against the Tide Caption: On 18 March 1975, the British Government approves, by 16 votes to 7, the outcomes of the renegotiation of the conditions for the United Kingdom's accession to the EEC, by virtue of which, the country decides to remain a member of the common market. In his memoirs, Tony Benn, the then Secretary of State for Industry, recalls the debates within the Government. Source: BENN, Tony. Against the Tide, Diaries 1973-1976. London: Hutchinson, 1989. 754 p. ISBN 0-09-173775-3. p. 342-349. Copyright: (c) Hutchinson URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/tony_benn_against_the_tide-en-d1481ab8-46ee-4c55-b124-c0996f94a6c3.html Last updated: 23/12/2014 1 / 7 23/12/2014 Tony Benn, Against the Tide [...] Tuesday 18 March A momentous day in the history of Britain – the day of the Cabinet decision on Europe, the day of the parliamentary decision, the day of the dissenting Ministers’ declaration, and of the Early Day Motion on the Order Paper. At Cabinet we had before us the papers detailing the renegotiation package, and for the first time the issue of sovereignty was discussed properly. The crucial question was whether the Community was to be a supranational structure or a community of sovereign states. Crosland wasn’t concerned with sovereignty because he thought sovereignty has passed anyway to the power workers and the hospital workers. He was concerned about the host of gratuitous harmonisations which he found he had to deal with. He said he would like this matter put to Ministers to try to stop it. -

Fcrhlislrflav

l.-4-4; ‘.-‘Li .-.. ” fcrhlislrflav '7August1982 V0143 No-113’, /5"’ __ —__ __ _ __ _ THE first resignation of a real grass-roots mafia and were now standing as ‘In depen- Labour Party Member of Parliament has dents’ — Mellish apparently believing that again brought bubbling to the surface the /75¢’,-14.: V56’? Wrzr me these ex-Labour members would serve tne seething undercurrents within the Labour yaw 5&5? .6’;/r//'1'/PEI’/5/%@, local people, and incidentally, the real Party. Labour party, better than the new boys. Mr Robert Mellish has been a member mmu/ax/na 5/as-115’4../an As it transpired, the Independents of the party since 1927 — 55 years. And --M 04/4 were successful, presumably because they for nearly 37 of those years he has been a DE?/£A0fi/I£A/I had a record of _ work in the local Member of Parliament for a dockiand 50418.0,’ community whereas the new ‘Militant’ constituency in South-East London - candidates did not - tn say nothing of Bermondsey. the campaigns in the media against the A great contribution of service to the Militant Tendency and all its devil work. working class, you might think — if you But Mellish’s support for Independents think that the Labour Party operates in / instead of for the official Labour candi- the interest of the working class, which dates, was enough to get him into consti- we don’t. tutional hot water from which even his In his time Bob Mellish has never friends in Westminster could not save him, achieved highest office in the party but \~\_ é if __4-—-Y- the National Executive Committee now in the various Labour Governments that having to allow a fresh selection confer- __._’_,_.._- have ruled us during the years he has been _.»- —- ence in Bermondsey for their favourite a faithful party hack -— and he did reach candidate in the next General Election. -

Labour's 'Broad Church'

ANGLIA RUSKIN UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF ARTS, LAW AND SOCIAL SCIENCES REACTION AND RENEWAL – LABOUR’S ‘BROAD CHURCH’ IN THE CONTEXT OF THE BREAKAWAY OF THE SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY 1979-1988 PAUL BLOOMFIELD A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Anglia Ruskin University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submitted: November 2017 Acknowledgements There are many people that I would like to thank for their help in the preparation of this thesis. I would like to thank first of all for their supervision and help with my research, my PhD Supervisory team of Dr Jonathan Davis and Professor Rohan McWilliam. Their patience, guidance, exacting thoroughness yet good humour have been greatly appreciated during the long gestation of this research work. For their kind acceptance in participating in the interviews that appear in this thesis, I would like to express my thanks and gratitude to former councillor and leader of Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council John Battye, Steve Garry and former councillor Jeremy Sutcliffe; the Right Honourable the Lord Bryan Davies of Oldham PC; the Right Honourable Frank Dobson MP; Labour activist Eddie Dougall; Baroness Joyce Gould of Potternewton; the Right Honourable the Baroness Dianne Hayter of Kentish Town; the Right Honourable the Lord Neil Kinnock of Bedwelty PC; Paul McHugh; Austin Mitchell MP; the Right Honourable the Lord Giles Radice PC; the Right Honourable the Lord Clive Soley of Hammersmith PC; and the Right Honourable Baroness Williams of Crosby. For their help and assistance I would like to thank the staff at the Labour History Archive and Study Centre, People’s History Museum, Central Manchester, Greater Manchester; the staff at the Neil Kinnock Archives, Churchill College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge; and the staff at the David Owen Archives, University of Liverpool, Special Collections and Archives Centre, Liverpool.