The National Life Story Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Bulletin | Issue 56: Autumn 2007 Images of Change

A BULLETIN OF THE HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT WHY OUR RURAL LANDSCAPESIssue 56: Autumn MA 2007 Issue 56: Autumn 2007 Issue Conservation bulletin 2 Editorial 3 Images of Change Modern Times 3 Change and creation 5 The post-industrial sublime 7 Social Landscapes 7 Post-war suburbs 9 New townscapes 11 The car: agent of transformation 13 People we knew 13 The M1 14 Opinion 15 Profitable Landscapes 15 Prairies and sheds? 17 Cars and chips 20 The ‘Sunrise Strip’ 21 Broadmead: art and heritage 22 Opinion 23 Political Landscapes 23 Recreating London 25 Artists and airmen 27 Hidden heritage 28 Architecture for the Welfare State 31 England’s atomic age 32 Opinion 33 Leisure and Pleasure 33 Taking a break 35 Popular music 36 Where the action was 37 The late 20th-century seabed 38 Making memoryscapes 38 Opinion 39 ‘It’s Turned Out Nice Again’ 41 Sex and shopping 41 News For many younger people, the buildings and landscapes of the late 20th 44 The National century are already heritage. So where does the historic environment Monuments Record begin and end? 46 Legal Developments 47 New Publications Built to celebrate the future in a disused china-clay quarry that is a monument to Cornwall’s industrial past, the Eden Project has become an icon of the new leisure culture of the early 21st century. Will it in turn become the heritage of tomorrow? © English Heritage.NMR Issue 56: Editorial: Modern Times Today’s landscapes have the potential to become tomorrow’s heritage, but how do we know what matters and what to preserve. -

Edward Maufe‟S Finest Church

Welcome to the Church of St Thomas the Apostle, Hanwell. Churches are unlike any other building. They are places for our daily and Sabbath prayers, and a focus for our community and family. They are the places for the important times of our lives, for births, weddings and funerals. They are places of interest and are often a centre for social history, art and music. However, primarily they direct our hearts to the God and the gospel and provide a centre for our interior pilgrimage. As you walk through the church and the surrounding land it is very much like a pilgrimage as so much of the building or artifacts remind you of God. Elain Harwood of English Heritage wrote in 1995 : This is Edward Maufe‟s finest church. Many people regard it as being more successful than his Guildford Cathedral and certainly more cohesive and richly detailed St Thomas‟ was paid for by the demolition of St Thomas‟, Portman Square. This church was in fact on Orchard Street and was built in 1858 by P. C. Hardwick. A reordering scheme was started in 1906 under the architect Arthur Blomfield and in 1911 a new reredos was ordered , designed by Cecil Hare, Bodley‟s last partner and successor to his practice. A drawing by Hare exists showing the reredos although by 1911 the entire funds has not been raised for its manufacture. This reredos was installed at St Thomas, Hanwell in 1934. The 3 manual Walker Organ also came from St Thomas‟ Portman Square. The building stands on land donated by the Earl of Jersey and it was he who laid the Foundation Stone on 8th July 1933. -

The Speaker of the House of Commons: the Office and Its Holders Since 1945

The Speaker of the House of Commons: The Office and Its Holders since 1945 Matthew William Laban Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 1 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I, Matthew William Laban, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of this thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: Details of collaboration and publications: Laban, Matthew, Mr Speaker: The Office and the Individuals since 1945, (London, 2013). 2 ABSTRACT The post-war period has witnessed the Speakership of the House of Commons evolving from an important internal parliamentary office into one of the most recognised public roles in British political life. This historic office has not, however, been examined in any detail since Philip Laundy’s seminal work entitled The Office of Speaker published in 1964. -

Assessment of Significance

HERITAGE AUDIT & STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ________________________________________ In respect of PLYMOUTH CITY CENTRE On behalf of GVA & PLYMOUTH CITY COUNCIL AHC REF: ND/PM/9235 Date: May 2014 www.assetheritage.co.uk 65 Banbury Road, Oxford, OX2 6PE T: 01865 310563 Registration No: 07502061 Heritage Audit GVA/Plymouth City Council Plymouth City Centre CONTENTS PAGE 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND SCOPE OF REPORT .................................................. 5 2.0 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ...................................................................... 8 3.0 THE CITY CENTRE TODAY: ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ................... 15 4.0 OPPORTUNITIES FOR CHANGE ............................................................. 106 5.0 SUMMARY AND PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS ...................................... 120 APPENDICES Appendix 1: Summary of Listed Buildings in Study Area FIGURES Fig.1.1 Modern plan summarising the interaction of surrounding designated conservation areas (reproduced on p.7). Fig.1.2 Modern Map of the Study Area showing buildings highlighted according to their significance as assessed in Section 3.0 (reproduced on p.27). Fig.1.3 Modern Map of the Study Area showing spaces highlighted according to their significance as assessed in Section 3.0 (reproduced on p.28). Fig.1.4 Modern plan summarising the divisions of the study area in Section 3.0 (reproduced on p.29 and p.107). Fig.1.5 Modern plan showing the areas which could best accommodate change on heritage grounds, as identified in Section 4.0 (reproduced on p.108). Fig.2 Abercrombie, 1943, 71. Zoning around the city centre. Fig.3 Architects’ Journal 12th June 1952 719. 1947 revised plan and construction up to 1952. Fig.4 Detail from Abercrombie, 1943, pl. facing 68. Fig.5 Detail from Abercrombie, 1943, pl. -

Text Cut Off in the Original 232 6

IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk TEXT CUT OFF IN THE ORIGINAL 232 6 ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE Between 1983 and 1989 there were a series of important changes to Party organisation. Some of these were deliberately pursued, some were more unexpected. All were critical causes, effects and aspects of the transformation. Changes occurred in PLP whipping, Party finance, membership administration, disciplinary procedures, candidate selection, the policy-making process and, most famously, campaign organisation. This chapter makes a number of assertions about this process of organisational change which are original and are inspired by and enhance the search for complexity. It is argued that the organisational aspect of the transformation of the 1980s resulted from multiple causes and the inter-retroaction of those causes rather than from one over-riding cause. In particular, the existing literature has identified organisational reform as originating with a conscious pursuit by the core leadership of greater control over the Party (Heffernan ~\ . !.. ~ and Marqusee 1992: passim~ Shaw 1994: 108). This chapter asserts that while such conscious .... ~.. ,', .. :~. pursuit was one cause, other factors such as ad hoc responses to events .. ,t~~" ~owth of a presidential approach, the use of powers already in existence and the decline of oppositional forces acted as other causes. This emphasis upon multiple causes of change is clearly in keeping with the search for complexity. 233 This chapter also represents the first detailed outline and analysis of centralisation as it related not just to organisational matters but also to the issue of policy-making. In the same vein the chapter is particularly significant because it relates the centralisation of policy-making to policy reform as it occurred between 1983 and 1987 not just in relation to the Policy Review as is the approach of previous analyses. -

Members 1979-2010

Members 1979-2010 RESEARCH PAPER 10/33 28 April 2010 This Research Paper provides a complete list of all Members who have served in the House of Commons since the general election of 1979 to the dissolution of Parliament on 12 April 2010. The Paper also provides basic biographical and parliamentary data. The Library and House of Commons Information Office are frequently asked for such information and this Paper is based on the data we collate from published sources to assist us in responding. This Paper replaces an earlier version, Research Paper 09/31. Oonagh Gay Richard Cracknell Jeremy Hardacre Jean Fessey Recent Research Papers 10/22 Crime and Security Bill: Committee Stage Report 03.03.10 10/23 Third Parties (Rights Against Insurers) Bill [HL] [Bill 79 of 2009-10] 08.03.10 10/24 Local Authorities (Overview and Scrutiny) Bill: Committee Stage Report 08.03.10 10/25 Northern Ireland Assembly Members Bill [HL] [Bill 75 of 2009-10] 09.03.10 10/26 Debt Relief (Developing Countries) Bill: Committee Stage Report 11.03.10 10/27 Unemployment by Constituency, February 2010 17.03.10 10/28 Transport Policy in 2010: a rough guide 19.03.10 10/29 Direct taxes: rates and allowances 2010/11 26.03.10 10/30 Digital Economy Bill [HL] [Bill 89 of 2009-10] 29.03.10 10/31 Economic Indicators, April 2010 06.04.10 10/32 Claimant Count Unemployment in the new (2010) Parliamentary 12.04.10 Constituencies Research Paper 10/33 Contributing Authors: Oonagh Gay, Parliament and Constitution Centre Richard Cracknell, Social and General Statistics Section Jeremy Hardacre, Statistics Resources Unit Jean Fessey, House of Commons Information Office This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. -

GO EAST: UNLOCKING the POTENTIAL of the THAMES ESTUARY Andrew Adonis, Ben Rogers and Sam Sims

GO EAST: UNLOCKING THE POTENTIAL OF THE THAMES ESTUARY Andrew Adonis, Ben Rogers and Sam Sims Published by Centre for London, February 2014 Open Access. Some rights reserved. Centre for London is a politically independent, As the publisher of this work, Centre for London wants to encourage the not-for-profit think tank focused on the big challenges circulation of our work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. facing London. It aims to help London build on its We therefore have an open access policy which enables anyone to access our content online without charge. Anyone can download, save, perform long history as a centre of economic, social, and or distribute this work in any format, including translation, without written intellectual innovation and exchange, and create a permission. This is subject to the terms of the Centre for London licence. fairer, more inclusive and sustainable city. Its interests Its main conditions are: range across economic, environmental, governmental and social issues. · Centre for London and the author(s) are credited Through its research and events, the Centre acts · This summary and the address www.centreforlondon.co.uk are displayed · The text is not altered and is used in full as a critical friend to London’s leaders and policymakers, · The work is not resold promotes a wider understanding of the challenges · A copy of the work or link to its use online is sent to Centre for London. facing London, and develops long-term, rigorous and You are welcome to ask for permission to use this work for purposes other radical solutions for the capital. -

This House Exploring the Play at Home

This House Exploring the Play at Home If you’re watching This House at home and would like to find out more out the production, there are a number of different resources that you can explore. About the Production This production of This House by James Graham was first performed at the National Theatre in 2012. The production was directed by Jeremy Herrin. The play explores life in the corridors of Westminster in 1974. You can find full details of the cast and production team below: Cast Labour Whips Bob Mellish: Phil Daniels Walter Harrison: Reece Dinsdale Michael Cocks/ Joe Harper: Vincent Franklin Ann Taylor: Lauren O’Neil Tory Whips Humphrey Atkins: Julian Wadham Jack Weatherill: Charles Edwards Fred Silvester: Ed Hughes The Members Chorus Clockmaker/Peebles/ Redditch/ Birmingham Perry Barr: Gunnar Cauthery Woolwich West/Batley & Morley/ Western Isles: Christopher Godwin Walsall North/Serjeant at Arms Act I/ Speaker Act II/Plymouth Sutton: Andrew Havill Rochester & Chatham/Welwyn & Hatfield/ Coventry South West/Lady Batley: Helena Lymbery Paddington South/Chelmsford/ South Ayrshire/Henley: Matthew Pidgeon Speaker Act I/Mansfield/ Serjeant at Arms Act II/ West Lothian: Giles Taylor Bromsgrove/Abingdon/ Liverpool Edge Hill/ Paisley/Fermanagh: Tony Turner Esher/Belfast West: Rupert Vansittart All other parts played by members of the Company Musicians Acoustic Jim & The Wires: Jim Hustwit (Music Director/guitar), Sam Edgington (bass) and Cristiano Castellitto (drums). Guest Vocals: Gunnar Cauthery and Phil Daniels Creative Team Director: Jeremy Herrin Designer: Rae Smith Lighting Designer: Paul Anderson Music: Stephen Warbeck Choreographer: Scott Ambler Sound Designer : Ian Dickinson Associate Director: Joe Murphy Original Lighting Designer: Paule Constable Company Voice Work: Richard Ryder Dialect Coach: Penny Dyer You might like to use the internet to research some of these artists to find out more about their careers. -

1986 Volume8 Number 1

ISS.:\ 02h 7-054 2 Planning History Bulletin 1986 Volume8 Number 1 PARKWAY T REATMENT OF HIGHWAY. Gu1erous provision of margi11s secures greater separalio11 of the dwellillt:S from the main roadway; allows space for ten11is or other recteations to be provided, or lum-out spaces where cars ca11 slop for repairs or picnic meal without obstructiot~ to the highway. Planning History Group - 1 - CHAIRMAN'S COMMUNICATION In the past , half the Executive of the Planning History Group has been elected annually , membership of those elected to :un CONTENTS for two years . Last year it was decided that the Execu~1ve 1 985-86 should continue for a further year, so no elect1ons were held last summer . There were then good reasons for an practices , but annual elections Chairman's Communication . .p • 1 i n terruption to our normal Editorial . .. ... p • 2 should now be resumed . Notices .. p • 3 F i r st , let me remind you of our present Executive : Reports of Meetings .. p • 7 Recent & Forthcoming Publications p.lO .. U. K. Non U. K. Research Reports: G.E . Cherry (Chairman)* A.F . J . Artibise M. J . Bannon 1. Chris Bacon "Deck Access Housing" p.l8 Patricia Garside (ex officio, 2 . Philip Booth "The Teaching of Pianning Membership Secretary) Eugenie Birch* History in Great Britain" p.21 D. Massey {ex officio, D.A. Brownell Treasurer) Christiane Collins G. Gordon J . B. Cullingworth* Articles: J . C. Hancock D. Hulchanski M. J . Hebbert (Editor) C. Silver Heather Norris Nicholson "Fortified Towns R. J.B. I<ain M. Smets* and Extension Planning in Nineteenth Helen Meller* J.B . -

A Century of Premiers: Salisbury to Blair

A Century of Premiers Salisbury to Blair Dick Leonard A Century of Premiers Also by Dick Leonard THE BACKBENCHER AND PARLIAMENT (ed. with Val Herman) CROSLAND AND NEW LABOUR (ed.) THE ECONOMIST GUIDE TO THE EUROPEAN UNION ELECTIONS IN BRITAIN: A Voter’s Guide (with Roger Mortimore) GUIDE TO THE GENERAL ELECTION PAYING FOR PARTY POLITICS THE PRO-EUROPEAN READER (ed. with Mark Leonard) THE SOCIALIST AGENDA: Crosland’s Legacy (ed. with David Lipsey) WORLD ATLAS OF ELECTIONS (with Richard Natkiel) A Century of Premiers Salisbury to Blair Dick Leonard © Dick Leonard 2005 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2005 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. -

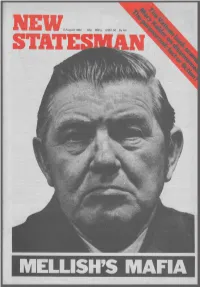

6August 1982

6 August 1982 The- real. mafia man vu lga r-minde dvand very much the he would not seek re-election) the Ber- Bob Mellish ha-sretired from the ", supporter of whoever is his boss at the mondsey Labour Party selected their sesre- Labour Party amid a blaze of . moment'. Mellish was an eager placeman, tary Peter Tatchell as the prospective- can- accusations of 'mafia tactics' and 'hit and has wanted 'desperately to be a Cabinet didate.' Mellish effectively 'blackmailed- Minister responsible for London and for Michael FOQt into. a public repudiation of lists' levelled at the London and housing. His political campaigning -and Tatchell. Although the meeting was secret BermondseyLabour Parties. personal platform has spanned a narrow at the time, the particulars are nQWknown. DUNCAN CAMPBELLreports ON Mt field, from orthodox catholic politics and Mellish threatened that he would resign' Mellish's career. sympathy for the Iberian dictatorships to forthwith if Tatchell were endorsed as can- persistent racialist attitudes-to immigrants didate by the Labour National Executive, HAD HE NOT RESIGNED from the and appeals to free East Enders like and would then campaign against him. Labour Party on Monday, Bob Mellish gangster Charlie Richardson and 'Scarface'. FOQt eventually _agreed to Mellish's de- faced certain expulsion this Friday at the Parsons (a well known robber in the mands leading to. the enormous and hands of West Lewisha:m Labour Party, 1950s). He has been associated; to his em- damaging public row last November. ' where he lives. This was because of his barrassment, .with three corrupt _ busi- Two. -

2015 CHARTER AWARDS GRAND PRIZE Iberville Offsites / P4

2015 CHARTER AWARDS GRAND PRIZE Iberville Offsites / P4 GRAND PRIZE / STUDENT Cities of a New Port Metropolis / P6 CHARTER AWARDS UCLA Weyburn / P8 Code SMTX: Tactical Urbanism Intervention and Project Kickoff / P9 Hunters View / P10 Pearl Brewery Redevelopment Master Plan / P11 Transit Oriented Development Revitalization / P12 Aldershot / P13 Virginia’s Capitol Master Plan / P14 30 Years of Scripps College Campus Stewardship / P15 Plan El Paso / P16 AWARDS OF MERIT Micro Lofts at The Arcade Providence / P17 Sullivan Station / P17 The Oval / P18 Arise / P18 Beaufort County Multijurisdictional Form-Based Code/Land Development Code / P19 University of Texas-Pan American Campus Master Plan / P19 Luhe City Center / P20 Sulphur Dell / P20 Master Plan for the Town of LaFox, Illinois / P21 Visions for Lafayette / P21 Mixed-use, walkable neighborhood development, as defined by the Charter of the New Urbanism, promotes healthier people, places, and economies. The members of CNU and their allies create positive change in communities all over the world. They design and build places people love. The Charter Awards, administered The Charter identifies three major scales Charter Awards are given to projects annually by CNU since 2001, celebrate of geography for design and policy at each scale, and special recognition the best work in this new era of purposes. The largest scale is composed is reserved for the best projects at the placemaking. The winners not only of regions. The middle scale is made up professional and student levels. Honored embody and advance the principles of of neighborhoods, districts, and corridors. by the world’s preeminent award for the Charter—they also make a difference The smallest scale is composed of blocks, urban design, winners set new standards in people’s lives.