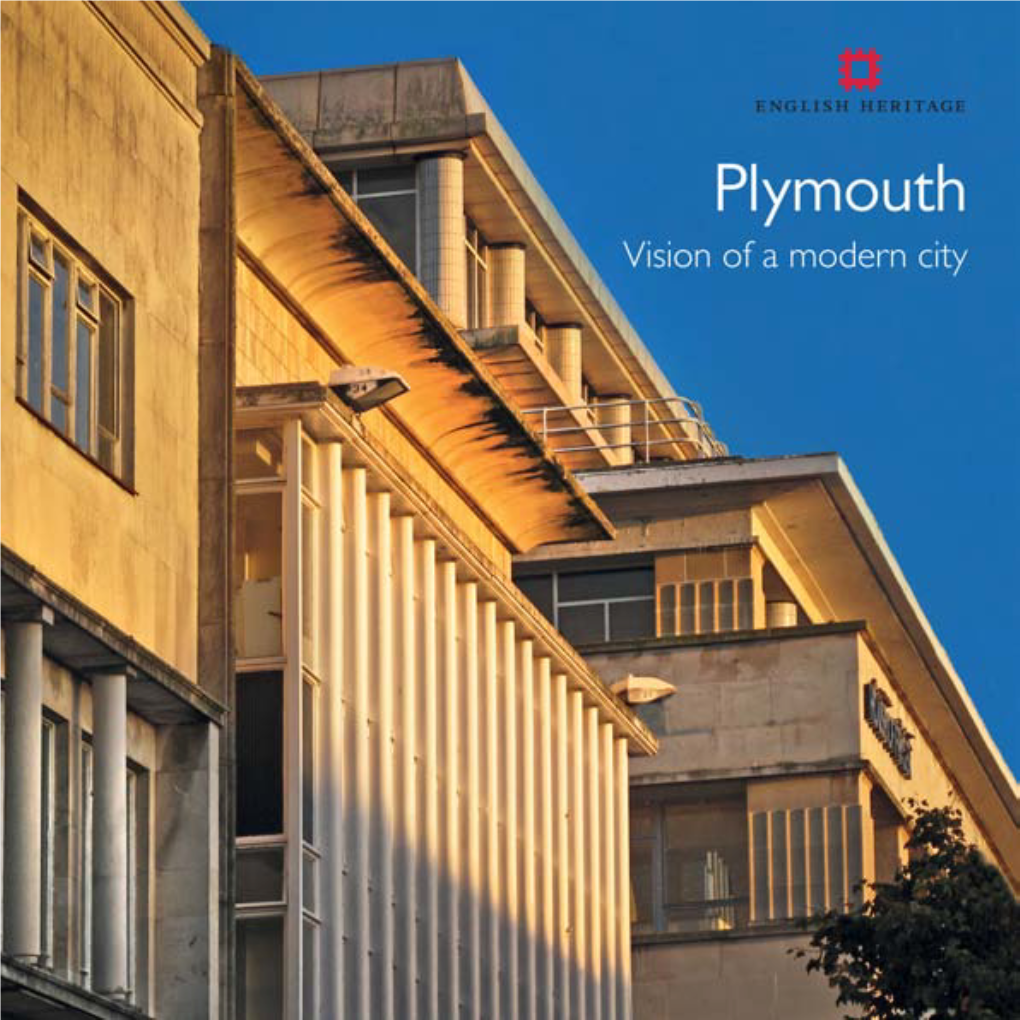

Plymouth Vision of a Modern City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Tree Maker

Ancestors of Grant Dennis Kish Peter Kis István Kiss b: 21 Apr 1694 in Pusky, Hungary Maria Kovacs István Kiss b: 10 Nov 1736 in Hédervár, Györ, Hungary Catharina Menyhart Thomas Kiss b: 07 Dec 1769 in Hédervár, Györ, Hungary Helena Hegedus Pál Kiss b: 03 Jan 1800 in Hédervár, Györ, Hungary m: 08 Feb 1820 in Hédervár, Györ, Hungary Juliana Angyál Mihály Kiss b: 19 Sep 1843 in Hédervár, Györ, Hungary m: 11 Feb 1868 in Hédervár, Györ, Hungary János Molnár János Molnár b: 30 Dec 1785 in Lipót, Moson, Hungary Gyorgy Nagy Anna Nagy b: 28 Feb 1766 in Darnó(Zseli), Moson, Hungary Rosalia Molnár Catharina Machovics b: 02 Sep 1802 in Lipót, Moson, Hungary Mihaly Asványi József Kiss b: 11 Mar 1882 in Hédervár, Györ, Hungary Elisabeth Asványi m: 24 Nov 1908 in Györujvaros, Gyor, Hungary b: 27 Mar 1786 in Lipót, Moson, Hungary d: 03 Apr 1977 in South Bend, St. Joseph, Indiana, USA Elisabeth Szalay István Jóós b: Bet. 1804 - 1829 in Asvanyi, Hungary m: 22 Jun 1845 in Hédervár, Györ, Hungary Terez Jóós Andreas Hegedüs b: 10 May 1850 in Hédervár, Györ, Hungary György Hegedüs b: 22 Feb 1796 in Hédervár, Györ, Hungary Eva Toth Dénes Kiss Maria Hegedüs b: 09 Oct 1909 in Hédervár, Györ, Hungary b: 02 Sep 1831 in Hédervár, Györ, Hungary m: 22 Jul 1933 in South Bend, Saint Joseph, Indiana d: 16 Jun 1996 in South Bend, St. Joseph, Indiana, Anna Ravasz USA János Kocsis János Kocsis b: Bet. 1853 - 1854 in Nagy Moriczhida, Györ, Hungary m: 08 Feb 1880 in Nagy Moriczhida, Györ, Hungary Vera Kocsis Julianna Kocsis b: 20 Feb 1887 in Nagy Moriczhida, Györ, Hungary József Radakovics d: 26 Nov 1966 in Massillon, Stark, Ohio, USA Mihály Radakovics b: in Nagy Morizchida, Györ, Hungary Julianna Kovacs Julianna Radakovics b: 13 Apr 1858 in Nagy Moriczhida, Györ, Dennis George Kish Hungary b: 07 Jun 1941 in South Bend, St. -

Predicting Fuel Poverty at the Local Level

Predicting fuel poverty at the local level Final report on the development of the Fuel Poverty Indicator William Baker & Graham Starling (CSE) David Gordon (University of Bristol) Research funded by Part of LE Group April 2003 Centre for Sustainable Energy The CREATE Centre Smeaton Road Bristol BS1 6XN Tel: 0117 929 9950 Fax: 0117 929 9114 Email: [email protected] Web: www.cse.org.uk Registered charity no.298740 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report has received support and comment from many people, too numerous to list here but to whom the authors would like to express their gratitude. However, we would particularly like to thank Chris Thomas, Energy Efficiency Projects Manager at SWEB, for his continuing support, interest and encouragement throughout the duration of the project. For further information on the Fuel Poverty Indicator contact: William Baker Senior Researcher Centre for Sustainable Energy [email protected] Predicting fuel poverty at the local level CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................... 5 2. DEVELOPMENT OF THE INDICATOR............................................................................................ 7 2.1 Background............................................................................................................................. 7 2.2 Measuring fuel poverty -

Al160207osa Market Coastal Towns

EEC/07/63/HQ Environment, Economy and Culture Overview/Scrutiny Committee 5 March 2007 Market and Coastal Towns Report of the Director of Environment, Economy and Culture 1. Summary In January 2006, members received a report on the draft Devon Sites and Premises Strategy and as a result expressed concern about the shortage of premises for smaller businesses. It was resolved that a further report be submitted, which covered economic development issues relating to Market Towns, including the availability of sites for relocation of small businesses and the Market and Coastal Town initiative (MCTi). This report concentrates on work undertaken in association with the MCTi pending further analysis of specific matters relevant to business premises. 2. Background In the South West, the MCTi commenced in 2000 and was led by the Regional Development Agency, Countryside Agency and English Heritage, with support from many other bodies. The scheme received greater emphasis following the incidence of Foot and Mouth Disease and a number of towns adversely affected were included in the programme. Since October 2004, delivery of the initiative has been charged to the Market and Coastal Towns Association (MCTA). This is an independent organisation largely funded by the Regional Development Agency, English Heritage and Big Lottery Fund. The initiative is a community based regeneration programme focusing on the preparation, by local people, of a long term Community Strategic Plan covering the social, economic, environmental and cultural features of their town and its hinterland. The MCTA delivers capacity building support to communities, enabling them to prepare the plans and develop their skills and organisational capacity while sharing good practice with others. -

Our Plan’, a New Strategic Plan for West Devon

Shaping our communities to 2031 Regulation 19 Publication Version February 2015 West Devon - A Leading Rural Council Foreword Welcome to ‘Our Plan’, a new strategic plan for West Devon. Whilst the Core Strategy was a plan for future growth and development to take us from 2006 to 2026, since it was written planning policy has undergone some significant changes as set out in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and we need to ensure our plans are fit for purpose and in conformity with this national policy. This new plan also has to cover a wider range of issues that go beyond traditional planning policy and it makes more sense to write a new plan rather than try and amend the existing ones. Therefore, ‘Our Plan’ will be the overarching strategic plan for the Borough of West Devon up to 2031. Developing a new plan is always challenging and it is often controversial with different sectors and individuals in our communities understandably seeing things from their own view point. However, we need to remember that we are planning for the communities of tomorrow not just for ourselves today. What we do now will have a significant impact on how people live their lives in West Devon in the future. Our biggest challenge is enabling growth and providing much needed homes and jobs whilst, at the same time, protecting the beautiful place that is West Devon - no mean feat as I’m sure you can appreciate. To do this we have gathered and considered evidence about local need and the views and comments shared by you and a wide range of partners during the process have helped us to shape a plan that we believe takes account of local needs and aspirations. -

Plym Valley Connections Heritage Lottery Fund Project

Designers of the London 2012 Olympic Parklands PLYM VALLEY CONNECTIONS HERITAGE LOTTERY FUND PROJECT LANDSCAPE CHARACTER AND HERITAGE ASSESSMENT AUGUST 2013 CONTENTS 1.0 FOREWORD 5 2.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 3.0 INTRODUCTION 10 4.0 APPROACH TO THE LCHA 12 5.0 METHODOLOGY 14 5.1. Guidance and Sources of Information 14 5.2. Study Area 15 6.0 OVERVIEW OF ASSESSMENT THEMES 16 6.1. Introduction 16 6.2. Physical Landscape and Natural Heritage 16 6.3. Cultural Heritage 22 6.4. People, Access and Places 30 6.5. Drivers for Change 33 7.0 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER AREAS 34 1. Coastal and Tidal Waters Landscape Character Type 36 2. Open Coastal Plateau and Cliffs Landscape Character Type 42 3. Lowland Plain Landscape Character Type 44 4. Wooded Valley and Farmland Landscape Character Type 46 5. Upland Fringes Landscape Character Type 54 6. Upland Moorland Landscape Character Type 62 7. Urban Landscape Character type 64 8.0 PROPOSED HLF BOUNDARY AND CONSIDERATIONS 66 9.0 CONCLUSIONS 68 APPENDICES 71 Appendix 1. Workshop Summary Findings Appendix 2. List of Significant Heritage Assets Appendix 3. Gazetteer of Environmental Assets Appendix 4. Landscape Character Overview FIGURES 4 1.0 FOREWORD “The longer one stays here the more does the spirit of the moor sink into one’s soul, its vastness, and also its grim charm. When you are once out upon its bosom you have left all traces of modern England behind you, but, on the other hand, you are conscious everywhere of the homes and the work of the prehistoric people. -

Easy-Going Dartmoor Guide (PDF)

Easy- Contents Introduction . 2 Key . 3 Going Dartmoor National Park Map . 4 Toilets . 6 Dartmoor Types of Walks . 8 Dartmoor Towns & Villages . 9 Access for All: A guide for less mobile Viewpoints . 26 and disabled visitors to the Dartmoor area Suggested Driving Route Guides . 28 Route One (from direction of Plymouth) . 29 Route Two (from direction of Bovey Tracey) . 32 Route Three (from direction of Torbay / Ashburton) . 34 Route Four (from direction of the A30) . 36 Further Information and Other Guides . 38 People with People Parents with People who Guided Walks and Events . 39 a mobility who use a pushchairs are visually problem wheelchair and young impaired Information Centres . 40 children Horse Riding . 42 Conservation Groups . 42 1 Introduction Dartmoor was designated a National Park in 1951 for its outstanding natural beauty and its opportunities for informal recreation. This information has been produced by the Dartmoor National Park Authority in conjunction with Dartmoor For All, and is designed to help and encourage those who are disabled, less mobile or have young children, to relax, unwind and enjoy the peace and quiet of the beautiful countryside in the Dartmoor area. This information will help you to make the right choices for your day out. Nearly half of Dartmoor is registered common land. Under the Dartmoor Commons Act 1985, a right of access was created for persons on foot or horseback. This right extends to those using wheelchairs, powered wheelchairs and mobility scooters, although one should be aware that the natural terrain and gradients may curb access in practice. Common land and other areas of 'access land' are marked on the Ordnance Survey (OS) map, Outdoor Leisure 28. -

Black's Guide to Devonshire

$PI|c>y » ^ EXETt R : STOI Lundrvl.^ I y. fCamelford x Ho Town 24j Tfe<n i/ lisbeard-- 9 5 =553 v 'Suuiland,ntjuUffl " < t,,, w;, #j A~ 15 g -- - •$3*^:y&« . Pui l,i<fkl-W>«? uoi- "'"/;< errtland I . V. ',,, {BabburomheBay 109 f ^Torquaylll • 4 TorBa,, x L > \ * Vj I N DEX MAP TO ACCOMPANY BLACKS GriDE T'i c Q V\ kk&et, ii £FC Sote . 77f/? numbers after the names refer to the page in GuidcBook where die- description is to be found.. Hack Edinburgh. BEQUEST OF REV. CANON SCADDING. D. D. TORONTO. 1901. BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/blacksguidetodevOOedin *&,* BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE TENTH EDITION miti) fffaps an* Hlustrations ^ . P, EDINBURGH ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK 1879 CLUE INDEX TO THE CHIEF PLACES IN DEVONSHIRE. For General Index see Page 285. Axniinster, 160. Hfracombe, 152. Babbicombe, 109. Kent Hole, 113. Barnstaple, 209. Kingswear, 119. Berry Pomeroy, 269. Lydford, 226. Bideford, 147. Lynmouth, 155. Bridge-water, 277. Lynton, 156. Brixham, 115. Moreton Hampstead, 250. Buckfastleigh, 263. Xewton Abbot, 270. Bude Haven, 223. Okehampton, 203. Budleigh-Salterton, 170. Paignton, 114. Chudleigh, 268. Plymouth, 121. Cock's Tor, 248. Plympton, 143. Dartmoor, 242. Saltash, 142. Dartmouth, 117. Sidmouth, 99. Dart River, 116. Tamar, River, 273. ' Dawlish, 106. Taunton, 277. Devonport, 133. Tavistock, 230. Eddystone Lighthouse, 138. Tavy, 238. Exe, The, 190. Teignmouth, 107. Exeter, 173. Tiverton, 195. Exmoor Forest, 159. Torquay, 111. Exmouth, 101. Totnes, 260. Harewood House, 233. Ugbrooke, 10P. -

Historical Notes Relating to Bideford's East-The-Water Shore.Odt

Historical Notes relating to Bideford's East-the-Water Shore A collection, in time-line form, of information pertaining primarily to the East-the-Water shore. Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................................13 Nature of this document.............................................................................................................13 Development of this document...................................................................................................13 Prior to written records...................................................................................................................13 Prehistory...................................................................................................................................13 Stone Age, flint tools and Eastridge enclosure............................................................................14 Roman period, tin roads, transit camps, and the ford..................................................................15 A Roman transit camp between two crossings.......................................................................15 An ancient tin route?.............................................................................................................15 The old ford...........................................................................................................................15 Saxon period, fisheries (monks and forts?).................................................................................15 -

Unlocking the Potential of the Global Marine Energy Industry 02 South West Marine Energy Park Prospectus 1St Edition January 2012 03

Unlocking the potential of the global marine energy industry 02 South West Marine Energy Park Prospectus 1st edition January 2012 03 The SOUTH WEST MARINE ENERGY PARK is: a collaborative partnership between local and national government, Local Enterprise Partnerships, technology developers, academia and industry a physical and geographic zone with priority focus for marine energy technology development, energy generation projects and industry growth The geographic scope of the South West Marine Energy Park (MEP) extends from Bristol to Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly, with a focus around the ports, research facilities and industrial clusters found in Cornwall, Plymouth and Bristol. At the heart of the South West MEP is the access to the significant tidal, wave and offshore wind resources off the South West coast and in the Bristol Channel. The core objective of the South West MEP is to: create a positive business environment that will foster business collaboration, attract investment and accelerate the commercial development of the marine energy sector. “ The South West Marine Energy Park builds on the region’s unique mix of renewable energy resource and home-grown academic, technical and industrial expertise. Government will be working closely with the South West MEP partnership to maximise opportunities and support the Park’s future development. ” Rt Hon Greg Barker MP, Minister of State, DECC The South West Marine Energy Park prospectus Section 1 of the prospectus outlines the structure of the South West MEP and identifies key areas of the programme including measures to provide access to marine energy resources, prioritise investment in infrastructure, reduce project risk, secure international finance, support enterprise and promote industry collaboration. -

Family and Heirs Sir Francis Drake

THE FAMILY AND HEIRS OF SIR FRANCIS DRAKE BY LADY ELIOTT-DRAKE WITH PORTRAITS AND ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. II. LONDON SMITH, ELDER & CO., 15 WATERLOO PLACE, S. W. 1911 [All rights reserved} THE FAMILY AND HEIRS OF SIR FRANCIS DRAKE VOL. II. cJ:-, · ,<Ji-a II c/.) (sf) ra l<e 9/1 ,·,v !J3CLl'O/l-et CONTENTS OF THE SECOND VOLUME PART V SIR FRANCIS DRAKE, THIRD BARONET, 1662-1717 OBAl'TER PAGE CBAl'TER PAGE I. 3 V. 117 II. 28 VI. 142 III. 55 VII. 169 IV. 87 VIII. 195 PART VI SIR FRANCIS HENRY DRAKE, FOURTH BARONET, 1718-1740 OBAPTER PAGE I. 211 PART VII SIR FRANCIS HENRY DRAKE, FIFTH BARONET, 1740-1794 CIIAl'TER PAGE CHAPTER PAGE I. 237 IV. 290 II. 253 V. 310 III. 276 VI. 332 PAGE APPENDIX l. 343 APPENDIX II. 360 INDEX • 403 ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE SECOND VOLUME Sm FRANCIS DRAKE, TmRD BARONET Frontispiece (From a Miniature b11 Sir Peter Lel11) DOROTHY, LADY DRAKE (DAUGHTER Ol!' SIR JOHN BAM• FIELD), WIFE OF TmRD BARONET To face p. 8 SIR HENRY POLLEXFEN, CmEF JUSTICE OF THE COMMON PLEAS • " 76 SAMFORD SPINEY CHURCH 138 ANNE, LADY DRAKE (DAUGHTER OF SAMUEL HEATHCOTE), WIFE OF FOURTH BARONET 218 SIR FRANCIS HENRY DRAKE, FOURTH BARONET 234 Sm FRANCIS HENRY DRAKE, FIFTH BARONET • 234 BEERALSTON 253 BUCKLAND ABBEY 274 Mrss KNIGHT 294 (F'rom a Painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds) ADMIRAL FRANCIS WII,LIAM DRAKE 310 DRAKE'S DRUM 338 PART V SIR FRANCIS DRAKE, 3RD BARONET 1662-1717 PARTY CHAPTER I As we pass from the life story of Sir Francis Drake, the ' Par liamentarian ' baronet, to that of his nephew and heir, Francis, only surviving son of Major Thomas Drake, we feel at first as though we were quitting old friends for the society of new and less interesting companions. -

Plymouth Airport Masterplan

Plymouth Airport Study Appendix C: Environmental Appraisal York Aviation February 2006 Faber Maunsell Plymouth Airport Study 2 Appendix C Table of Contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Airport Description ................................................................................................ 4 1.2 Airport Expansion.................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Options for Expansion of the Airport..................................................................... 5 2 Air Quality ........................................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Scope of the Assessment ..................................................................................... 7 2.2 Method .................................................................................................................. 7 2.3 Baseline Desk Study............................................................................................. 7 2.4 Air Quality at the Airport........................................................................................ 8 2.5 Assessment of Effects of the Proposed Airport Extension on Air Quality and Climate.................................................................................................................. 9 3 Ecology ......................................................................................................................... -

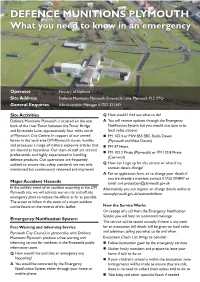

DEFENCE MUNITIONS PLYMOUTH What You Need to Know in an Emergency

DEFENCE MUNITIONS PLYMOUTH What you need to know in an emergency Operator Ministry of Defence Site Address Defence Munitions Plymouth, Ernesettle Lane, Plymouth PL5 2TQ General Enquiries Administration Manager 01752 321342 Site Activities Q How would I find out what to do? Defence Munitions Plymouth is situated on the east A You will receive updates through the Emergency bank of the river Tamar between the Tamar Bridge Notification System but you should also tune in to and Ernesettle Lane, approximately four miles north local radio stations: of Plymouth City Centre. In support of our armed n FM: 103.4 or MW 855 BBC Radio Devon forces in the local area DM Plymouth stores, handles (Plymouth and West Devon) and processes a range of military explosive articles that n FM: 97 Heart are classed as hazardous. Our team of staff are trained n FM: 102.2 Pirate (Plymouth) or FM 102.8 Pirate professionals and highly experienced in handling (Cornwall) defence products. Our operations are frequently audited to ensure that safety standards are not only Q How can I sign up for this service or what if my maintained but continuously reviewed and improved. contact details change? A For an application form, or to change your details if you are already a member, contact 01752 304847 or Major Accident Hazards email: [email protected] In the unlikely event of an accident occurring at the DM Alternatively you can register or change details online at: Plymouth site, we will activate our on site and off site www.plymouth.gov.uk/warnandinform emergency plans to reduce the effects as far as possible.