2015 Passmore Michael 1069

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOM Magazine No

2020 DOM magazine 04 December The Art of Books and Buildings The Cities of Tomorrow Streets were suddenly empty, and people began to flee to the countryside. The corona virus pandemic has forced us to re- think urban design, which is at the heart of this issue. From the hotly debated subject of density to London’s innovative social housing through to Berlin’s creative spaces: what will the cities of the future look like? See pages 14 to 27 PORTRAIT The setting was as elegant as one would expect from a dig- Jean-Philippe Hugron, nified French institution. In late September, the Académie Architecture Critic d’Architecture – founded in 1841, though its roots go back to pre- revolutionary France – presented its awards for this year. The Frenchman has loved buildings since The ceremony took place in the institution’s rooms next to the childhood – the taller, the better. Which Place des Vosges, the oldest of the five ‘royal squares’ of Paris, is why he lives in Paris’s skyscraper dis- situated in the heart of the French capital. The award winners trict and is intrigued by Monaco. Now he included DOM publishers-author Jean-Philippe Hugron, who has received an award from the Académie was honoured for his publications. The 38-year-old critic writes d’Architecture for his writing. for prestigious French magazines such as Architecture d’au jourd’hui and Exé as well as the German Baumeister. Text: Björn Rosen Hugron lives ten kilometres west of the Place des Vosges – and architecturally in a completely different world. -

Residential Update

Residential update UK Residential Research | January 2018 South East London has benefitted from a significant facelift in recent years. A number of regeneration projects, including the redevelopment of ex-council estates, has not only transformed the local area, but has attracted in other developers. More affordable pricing compared with many other locations in London has also played its part. The prospects for South East London are bright, with plenty of residential developments raising the bar even further whilst also providing a more diverse choice for residents. Regeneration catalyst Pricing attraction Facelift boosts outlook South East London is a hive of residential Pricing has been critical in the residential The outlook for South East London is development activity. Almost 5,000 revolution in South East London. also bright. new private residential units are under Indeed pricing is so competitive relative While several of the major regeneration construction. There are also over 29,000 to many other parts of the capital, projects are completed or nearly private units in the planning pipeline or especially compared with north of the river, completed there are still others to come. unbuilt in existing developments, making it has meant that the residential product For example, Convoys Wharf has the it one of London’s most active residential developed has appealed to both residents potential to deliver around 3,500 homes development regions. within the area as well as people from and British Land plan to develop a similar Large regeneration projects are playing further afield. number at Canada Water. a key role in the delivery of much needed The competitively-priced Lewisham is But given the facelift that has already housing but are also vital in the uprating a prime example of where people have taken place and the enhanced perception and gentrification of many parts of moved within South East London to a more of South East London as a desirable and South East London. -

Hundreds of Homes for Sale See Pages 3, 4 and 5

Wandsworth Council’s housing newsletter Issue 71 July 2016 www.wandsworth.gov.uk/housingnews Homelife Queen’s birthday Community Housing cheat parties gardens fined £12k page 10 and 11 Page 13 page 20 Hundreds of homes for sale See pages 3, 4 and 5. Gillian secured a role at the new Debenhams in Wandsworth Town Centre Getting Wandsworth people Sarah was matched with a job on Ballymore’s Embassy Gardens into work development in Nine Elms. The council’s Work Match local recruitment team has now helped more than 500 unemployed local people get into work and training – and you could be next! The friendly team can help you shape up your CV, prepare for interview and will match you with a live job or training vacancy which meets your requirements. Work Match Work They can match you with jobs, apprenticeships, work experience placements and training courses leading to full time employment. securing jobs Sheneiqua now works for Wandsworth They recruit for dozens of local employers including shops, Council’s HR department. for local architects, professional services, administration, beauti- cians, engineering companies, construction companies, people supermarkets, security firms, logistics firms and many more besides. Work Match only help Wandsworth residents into work and it’s completely free to use their service. Get in touch today! w. wandsworthworkmatch.org e. [email protected] t. (020) 8871 5191 Marc Evans secured a role at 2 [email protected] Astins Dry Lining AD.1169 (6.16) Welcome to the summer edition of Homelife. Last month, residents across the borough were celebrating the Queen’s 90th (l-r) Cllr Govindia and CE Nick Apetroaie take a glimpse inside the apartments birthday with some marvellous street parties. -

Johnson 1 C. Johnson: Social Contract And

C. Johnson: Social Contract and Energy in Pimlico ORIGINAL ARTICLE District heating as heterotopia: Tracing the social contract through domestic energy infrastructure in Pimlico, London Charlotte Johnson UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources, University College London, London, WC1H 0NN, UK Corresponding author: Charlotte Johnson; e-mail: [email protected] The Pimlico District Heating Undertaking (PDHU) was London’s first attempt at neighborhood heating. Built in the 1950s to supply landmark social housing project Churchill Gardens, the district heating system sent heat from nearby Battersea power station into the radiators of the housing estate. The network is a rare example in the United Kingdom, where, unlike other European states, district heating did not become widespread. Today the heating system supplies more than 3,000 homes in the London Borough of Westminster, having survived the closure of the power station and the privatization of the housing estate it supplies. Therefore, this article argues, the neighborhood can be understood as a heterotopia, a site of an alternative sociotechnical order. This concept is used to understand the layers of economic, political, and technological rationalities that have supported PDHU and to question how it has survived radical changes in housing and energy policy in the United Kingdom. This lens allows us to see the tension between the urban planning and engineering perspective, which celebrates this Johnson 1 system as a future-oriented “experiment,” and the reality of managing and using the system on the estate. The article analyzes this technology-enabled standard of living as a social contract between state and citizen, suggesting a way to analyze contemporary questions of district energy. -

MS 315 A1076 Papers of Clemens Nathan Scrapbooks Containing

1 MS 315 A1076 Papers of Clemens Nathan Scrapbooks containing newspaper cuttings, correspondence and photographs from Clemens Nathan’s work with the Anglo-Jewish Association (AJA) 1/1 Includes an obituary for Anatole Goldberg and information on 1961-2, 1971-82 the Jewish youth and Soviet Jews 1/2 Includes advertisements for public meetings, information on 1972-85 the Middle East, Soviet Jews, Nathan’s election as president of the Anglo-Jewish Association and a visit from Yehuda Avner, ambassador of the state of Israel 1/3 Including papers regarding public lectures on human rights 1983-5 issues and the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, the Middle East, human rights and an obituary for Leslie Prince 1/4 Including papers regarding the Anglo-Jewish Association 1985-7 (AJA) president’s visit to Israel, AJA dinner with speaker Timothy Renton MP, Minister of State for the Foreign and Commonwealth Office; Kurt Waldheim, president of Austria; accounts for 1983-4 and an obituary for Viscount Bearsted Papers regarding Nathan’s work with the Consultative Council of Jewish Organisations (CCJO) particularly human rights issues and printed email correspondence with George R.Wilkes of Gonville and Cauis Colleges, Cambridge during a period when Nathan was too ill to attend events and regarding the United Nations sub- commission on human right at Geneva. [The CCJO is a NGO (Non-Governmental Organisation) with consultative status II at UNESCO (the United National Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation)] 2/1 Papers, including: Jan -Aug 1998 arrangements -

City Villages: More Homes, Better Communities, IPPR

CITY VILLAGES MORE HOMES, BETTER COMMUNITIES March 2015 © IPPR 2015 Edited by Andrew Adonis and Bill Davies Institute for Public Policy Research ABOUT IPPR IPPR, the Institute for Public Policy Research, is the UK’s leading progressive thinktank. We are an independent charitable organisation with more than 40 staff members, paid interns and visiting fellows. Our main office is in London, with IPPR North, IPPR’s dedicated thinktank for the North of England, operating out of offices in Newcastle and Manchester. The purpose of our work is to conduct and publish the results of research into and promote public education in the economic, social and political sciences, and in science and technology, including the effect of moral, social, political and scientific factors on public policy and on the living standards of all sections of the community. IPPR 4th Floor 14 Buckingham Street London WC2N 6DF T: +44 (0)20 7470 6100 E: [email protected] www.ippr.org Registered charity no. 800065 This book was first published in March 2015. © 2015 The contents and opinions expressed in this collection are those of the authors only. CITY VILLAGES More homes, better communities Edited by Andrew Adonis and Bill Davies March 2015 ABOUT THE EDITORS Andrew Adonis is chair of trustees of IPPR and a former Labour cabinet minister. Bill Davies is a research fellow at IPPR North. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The editors would like to thank Peabody for generously supporting the project, with particular thanks to Stephen Howlett, who is also a contributor. The editors would also like to thank the Oak Foundation for their generous and long-standing support for IPPR’s programme of housing work. -

Neighbourhoods in England Rated E for Green Space, Friends of The

Neighbourhoods in England rated E for Green Space, Friends of the Earth, September 2020 Neighbourhood_Name Local_authority Marsh Barn & Widewater Adur Wick & Toddington Arun Littlehampton West and River Arun Bognor Regis Central Arun Kirkby Central Ashfield Washford & Stanhope Ashford Becontree Heath Barking and Dagenham Becontree West Barking and Dagenham Barking Central Barking and Dagenham Goresbrook & Scrattons Farm Barking and Dagenham Creekmouth & Barking Riverside Barking and Dagenham Gascoigne Estate & Roding Riverside Barking and Dagenham Becontree North Barking and Dagenham New Barnet West Barnet Woodside Park Barnet Edgware Central Barnet North Finchley Barnet Colney Hatch Barnet Grahame Park Barnet East Finchley Barnet Colindale Barnet Hendon Central Barnet Golders Green North Barnet Brent Cross & Staples Corner Barnet Cudworth Village Barnsley Abbotsmead & Salthouse Barrow-in-Furness Barrow Central Barrow-in-Furness Basildon Central & Pipps Hill Basildon Laindon Central Basildon Eversley Basildon Barstable Basildon Popley Basingstoke and Deane Winklebury & Rooksdown Basingstoke and Deane Oldfield Park West Bath and North East Somerset Odd Down Bath and North East Somerset Harpur Bedford Castle & Kingsway Bedford Queens Park Bedford Kempston West & South Bedford South Thamesmead Bexley Belvedere & Lessness Heath Bexley Erith East Bexley Lesnes Abbey Bexley Slade Green & Crayford Marshes Bexley Lesney Farm & Colyers East Bexley Old Oscott Birmingham Perry Beeches East Birmingham Castle Vale Birmingham Birchfield East Birmingham -

JLTC Playscript

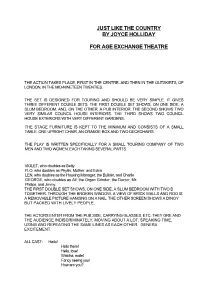

JUST LIKE THE COUNTRY BY JOYCE HOLLIDAY FOR AGE EXCHANGE THEATRE THE ACTION TAKES PLACE, FIRST IN THE CENTRE, AND THEN IN THE OUTSKIRTS, OF LONDON, IN THE MID-NINETEEN TWENTIES. THE SET IS DESIGNED FOR TOURING AND SHOULD BE VERY SIMPLE. IT GIVES THREE DIFFERENT DOUBLE SETS. THE FIRST DOUBLE SET SHOWS, ON ONE SIDE, A SLUM BEDROOM, AND, ON THE OTHER, A PUB INTERIOR. THE SECOND SHOWS TWO VERY SIMILAR COUNCIL HOUSE INTERIORS. THE THIRD SHOWS TWO COUNCIL HOUSE EXTERIORS WITH VERY DIFFERENT GARDENS. THE STAGE FURNITURE IS KEPT TO THE MINIMUM AND CONSISTS OF A SMALL TABLE, ONE UPRIGHT CHAIR, AN ORANGE BOX AND TWO DECKCHAIRS. THE PLAY IS WRITTEN SPECIFICALLY FOR A SMALL TOURING COMPANY OF TWO MEN AND TWO WOMEN, EACH TAKING SEVERAL PARTS. VIOLET, who doubles as Betty FLO, who doubles as Phyllis, Mother, and Edna LEN, who doubles as the Housing Manager, the Builder, and Charlie GEORGE, who doubles as Alf, the Organ Grinder, the Doctor, Mr. Phillips, and Jimmy. THE FIRST DOUBLE SET SHOWS, ON ONE SIDE, A SLUM BEDROOM WITH TWO B TOGETHER. THROUGH THE BROKEN WINDOW, A VIEW OF BRICK WALLS AND ROO IS A REMOVABLE PICTURE HANGING ON A NAIL. THE OTHER SCREEN SHOWS A DINGY BUT PACKED WITH LIVELY PEOPLE. THE ACTORS ENTER FROM THE PUB SIDE, CARRYING GLASSES, ETC. THEY GRE AND THE AUDIENCE INDISCRIMINATELY, MOVING ABOUT A LOT, SPEAKING TIME, USING AND REPEATING THE SAME LINES AS EACH OTHER. GENERA EXCITEMENT. ALL CAST: Hello! Hello there! Hello, love! Watcha, mate! Fancy seeing you! How are you? How're you keeping? I'm alright. -

2017 09 19 South Lambeth Estate

LB LAMBETH EQUALITY IMPACT ASSESSMENT August 2018 SOUTH LAMBETH ESTATE REGENERATION PROGRAMME www.ottawaystrategic.co.uk $es1hhqdb.docx 1 5-Dec-1810-Aug-18 Equality Impact Assessment Date August 2018 Sign-off path for EIA Head of Equalities (email [email protected]) Director (this must be a director not responsible for the service/policy subject to EIA) Strategic Director or Chief Exec Directorate Management Team (Children, Health and Adults, Corporate Resources, Neighbourhoods and Growth) Procurement Board Corporate EIA Panel Cabinet Title of Project, business area, Lambeth Housing Regeneration policy/strategy Programme Author Ottaway Strategic Management Ltd Job title, directorate Contact email and telephone Strategic Director Sponsor Publishing results EIA publishing date EIA review date Assessment sign off (name/job title): $es1hhqdb.docx 2 5-Dec-1810-Aug-18 LB Lambeth Equality Impact Assessment South Lambeth Estate Regeneration Programme Independently Reported by Ottaway Strategic Management ltd August 2018 Contents EIA Main Report 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 4 2 Introduction and context ....................................................................................... 12 3 Summary of equalities evidence held by LB Lambeth ................................................ 17 4 Primary Research: Summary of Household EIA Survey Findings 2017 ........................ 22 5 Equality Impact Assessment .................................................................................. -

Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities This Page Intentionally Left Blank H6309-Prelims.Qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page Iii

H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page i Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities This page intentionally left blank H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page iii Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities Mike Jenks and Nicola Dempsey AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON • NEW YORK • OXFORD PARIS • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Architectural Press is an imprint of Elsevier H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page iv Architectural Press An imprint of Elsevier Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 30 Corporate Drive, Burlington, MA 01803 First published 2005 Editorial matter and selection Copyright © 2005, Mike Jenks and Nicola Dempsey. All rights reserved Individual contributions Copyright © 2005, the Contributors. All rights reserved No parts of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1T 4LP. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science and Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (ϩ44) (0) 1865 843830; fax: (ϩ44) (0) 1865 853333; e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://www.elsevier.com), by selecting ‘Customer Support’ and then ‘Obtaining Permissions’. -

2017 Annual Report Plc Redrow Sense of Wellbeing

Redrow plc Redrow Redrow plc Redrow House, St. David’s Park, Flintshire CH5 3RX 2017 Tel: 01244 520044 Fax: 01244 520720 ANNUAL REPORT Email: [email protected] Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 01 STRATEGIC REPORT STRATEGIC REDROW ANNUAL REPORT 2017 A Better Highlights Way to Live £1,660m £315m 70.2p £1,382m £250m 55.4p £1,150m £204m 44.5p GOVERNANCE REPORT GOVERNANCE 15 16 17 15 16 17 15 16 17 £1,660m £315m 70.2p Revenue Profit before tax Earnings per share +20% +26% +27% 17p 5,416 £1,099m 4,716 £967m STATEMENTS FINANCIAL 4,022 10p £635m 6p 15 16 17 15 16 17 15 16 17 Contents 17p 5,416 £1,099m Dividend per share Legal completions (inc. JV) Order book (inc. JV) SHAREHOLDER INFORMATION SHAREHOLDER STRATEGIC REPORT GOVERNANCE REPORT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SHAREHOLDER 01 Highlights 61 Corporate Governance 108 Independent Auditors’ INFORMATION +70% +15% +14% 02 Our Investment Case Report Report 148 Corporate and 04 Our Strategy 62 Board of Directors 114 Consolidated Income Shareholder Statement Information 06 Our Business Model 68 Audit Committee Report 114 Statement of 149 Five Year Summary 08 A Better Way… 72 Nomination Committee Report Comprehensive Income 16 Our Markets 74 Sustainability 115 Balance Sheets Award highlights 20 Chairman’s Statement Committee Report 116 Statement of Changes 22 Chief Executive’s 76 Directors’ Remuneration in Equity Review Report 117 Statement of Cash Flows 26 Operating Review 98 Directors’ Report 118 Accounting Policies 48 Financial Review 104 Statement of Directors’ 123 Notes to the Financial 52 Risk -

Rückkehr Der Wohnmaschinen

Maren Harnack Rückkehr der Wohnmaschinen Architekturen | Band 10 Maren Harnack (Dr.-Ing.) studierte Architektur, Stadtplanung und Sozialwis- senschaften in Stuttgart, Delft und London. Sie arbeitete als wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin an der HafenCity Universtät in Hamburg und ist seit 2011 Pro- fessorin für Städtebau an der Fachhochschule Frankfurt am Main. Daneben ist sie freie Stadtplanerin, freie Architektin, wirkte an zahlreichen Forschungspro- jekten mit und publiziert regelmäßig in den Fachmedien. Maren Harnack Rückkehr der Wohnmaschinen Sozialer Wohnungsbau und Gentrifizierung in London Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde im Herbst 2010 von der HafenCity Universität Hamburg als Dissertation angenommen. Gutachter waren Prof. Dr. sc. techn. ETH Michael Koch und Prof. Dr. phil. Martina Löw. Die mündliche Prüfung fand am 21. Oktober 2010 statt. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © 2012 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Die Verwertung der Texte und Bilder ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages ur- heberrechtswidrig und strafbar. Das gilt auch für Vervielfältigungen, Überset- zungen, Mikroverfilmungen und für die Verarbeitung mit elektronischen Sys- temen. Umschlaggestaltung: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Umschlagabbildung: Martin Kohler Lektorat: Gabriele Roy, Ingar Milnes, Bernd Harnack Satz: Maren Harnack Druck: Majuskel Medienproduktion