The Potters Humme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RSG Frankenhof Sonnefeld E.V

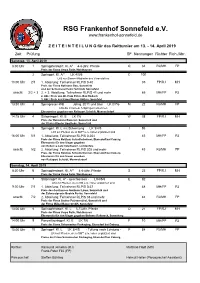

RSG Frankenhof Sonnefeld e.V. www.frankenhof-sonnefeld.de Z E I T E I N T E I L U N G für das Reitturnier am 13. - 14. April 2019 Zeit Prüfung SF Nennungen Richter Rich./Abr. Samstag, 13. April 2019 8:30 Uhr 1 Springpferdeprf. Kl. A* 4-6-jähr. Pferde Q 34 RJ/MH FP Preis der Firma Verpa Folie, Weidhausen 2 Springprf. Kl. A** LK 4/5/6 C 100 LK6 nur Stamm-Mitglieder des Veranstalters 10:00 Uhr 2/1 1. Abteilung: Teilnehmer RLP/S 0-40 35 FP/RJ MH Preis der Firma Hofmann Bau, Sonnefeld und der Schreinerei Heinz Schmidt, Sonnefeld anschl. 2/2 + 3 2. + 3. Abteilung: Teilnehmer RLP/S 41 und mehr 65 MH/FP RJ 2. Abt.: Preis von Dr. Hajo Pohle, Bad Rodach 3. Abt.: Preis der Firma Werner Höllein, Sonnfeld 13:30 Uhr 3 Springreiter-WB Jahrg. 2011 und älter LK 0/7/6 M 22 RJ/MH FP LK6 die in keinem A-Springen teilnehmen Ehrenpreise gegeben von Reitsport Scheidt, Memmelsdorf 14:15 Uhr 4 Stilspringprf. Kl. E LK 7/6 W 38 FP/RJ MH Preis der Reinigung Ramster, Sonnefeld und der Vitalen Kloster Apotheke, Sonnefeld 5 Springprf. Kl. L mit Stilwertung LK 3/4/5 I 86 LK3 mit Pferden die in SM** u./o. höher unplatziert sind 16:00 Uhr 5/1 1. Abteilung: Teilnehmer RLP/S 0-204 43 MH/FP RJ Preis der Firma Holzbau Schleifenheimer, Ebersdorf bei Coburg Ehrenpreis für den Sieger gegeben von Rebecca Lutz Vetphysio+, Lichtenfels anschl. 5/2 2. -

Standort Oberfranken

Funkanalyse Bayern 2017 Standort Oberfranken Saale-Holzland- Zwickau Gotha Kreis Ilm-Kreis Greiz Schmalkalden- Meiningen Saalfeld- Rudolstadt Suhl Saale- Orla-Kreis Ludwigsstadt Hildburghausen Tettau Vogtlandkreis * * Steinbach Reichenbach am Wald Sonneberg Tschirn Teuschnitz Töpen Lichtenberg Issigau * Berg Trogen Nordhalben Feilitzsch Lautertal Bad Pressig * Steben * Geroldsgrün Coburg Köditz Gattendorf Bad Rodach Neustadt Rhön- Meeder Selbitz bei Coburg * HofNaila Steinwiesen Leupoldsgrün Regnitzlosau Grabfeld Rödental Stockheim Hof * Döhlau * Schwarzenbach am Schauenstein Dörfles-Esbach Wilhelmsthal Wallenfels Wald * Kronach Konradsreuth Oberkotzau Ebersdorf Coburg Mitwitz Marktrodach Helmbrechts Rehau Weitramsdorf bei Presseck Grub am Sonnefeld Forst Coburg Schwarzenbach Weidhausen Schönwald Ahorn Niederfüllbach Kronach Grafengehaig an der Saale bei Schneckenlohe Coburg Rugendorf Münchberg * Seßlach Untersiemau Redwitz an Küps Weißenbrunn Marktleugast Weißdorf Selb * Marktgraitz der Stadtsteinach Großheirath Michelau in * * Oberfranken Rodach Guttenberg * Marktzeuln Sparneck * Stammbach Kirchenlamitz Burgkunstadt Zell im Untersteinach Kupferberg * * Lichtenfels Fichtelgebirge Thierstein Hohenberg Itzgrund Hochstadt Ludwigschorgast * Marktleuthen Kulmbach an der am Main Altenkunstadt Wirsberg Weißenstadt Höchstädt im Eger Bad Lichtenfels Neuenmarkt Mainleus Gefrees Fichtelgebirge * Staffelstein Ködnitz Thiersheim Schirnding Ebern * Marktschorgast Röslau Kulmbach Bad Rattelsdorf Ebensfeld Trebgast Bischofsgrün WunsiedelTröstau i. Arzberg -

Ausflugsziele in Neustadt B.Coburg Und Umgebung

Ausflugsziele in Neustadt b.Coburg und Umgebung NEUSTADT BEI COBURG (BAYERN) Arnoldhütte mit Prinzregententurm auf dem Muppberg (ca. 31 Min. / 1,7 km)* und Max-Oscar-Arnold-Wanderweg Muppberg, 96465 Neustadt bei Coburg Tel.: +49 (0) 9568 5917 Transfer per Muppberg-Linie jeden Freitagnachmittag Tel.: +49 (0) 9568 81-139 www.neustadt-bei-coburg.de/tourismus/sehenswuerdigkeiten/muppberg BIG – Bildungsstätte Innerdeutsche Grenze ( ca. 3 Min. / 1,1 km) kultur.werk.stadt, Bahnhofstr. 22, 96465 Neustadt bei Coburg Tel.: +49 (0) 9568 81-139 Die alte Weihnachtsfabrik mit Historischem Weihnachtsmuseum ( ca. 5 Min. / 3,4 km) Sternenweg 2, 96465 Neustadt bei Coburg Tel.: +49 (0) 9568 857-0 www.inge-glas.de/unternehmen/alte-weihnachtsfabrik Familienbad/Hallenbad bademehr mit Dampfsauna und Wellenbetrieb ( ca. 4 Min. / 1,3 km) Wildenheider Str. 11, 96465 Neustadt bei Coburg Tel.: +49 (0) 9568 891990 www.bademehr.de/familienbad Freibad Märchenbad ( ca. 5 Min. / 1,4 km) Am Moos, 96465 Neustadt bei Coburg Tel.: +49 (0) 9568 852-39 www.bademehr.de/maerchenbad Freizeitpark „Villeneuve-sur-Lot“ ( ca. 5 Min. / 1,4 km) Am Moos, 96465 Neustadt bei Coburg Tel.: +49 (0) 9568 81-139 www.neustadt-bei-coburg.de/tourismus/freizeiteinrichtungen/freizeitpark Max-Oscar-Arnold-Denkmal ( ca. 3 Min. / 0,7 km) Arnoldplatz, 96465 Neustadt bei Coburg Museum der Deutschen Spielzeugindustrie ( ca. 3 Min. / 0,7 km) Hindenburgplatz 1, 96465 Neustadt bei Coburg Tel.: +49 (0) 9568 5600 www.spielzeugmuseum-neustadt.de Rad- und Wanderwegenetz („Lutherweg“, „Iron-Curtain-Trail“, „Grünes Band“) www.frankentourismus.de/orte/neustadt_bcoburg-341 www.coburg-rennsteig.de/de/urlaubswelten/natur-aktiv/wandern-walken * Berechnung aller Entfernungen/Zeitangaben ausgehend vom Stadtzentrum (Marktplatz) in Neustadt bei Coburg Ausflugsziele in Neustadt b.Coburg und Umgebung Stadtkirche St. -

GRÜN Bewegt Den Kreistag GRÜN Bewegt Den Kreistag

Zeit für GRÜN! Dagmar Escher (Kreisrätin, Gemeinderätin) Bernd Lauterbach (Kreisrat, Gemeinderat) Gabriele Jahn (Kreisrätin, Gemeinderätin) Ulrich Leicht (Kreisrat, Stadtrat) Felicitas Medau GRÜN bewegt den Kreistag GRÜN bewegt den Kreistag Bad Rodach Meeder Gerda Fleddermann Thomas Kreisler Thomas Ziesmer Aldo Lütgenau Erika Wallmann Werner Zoufal Helmut Jakobi Klaus Freitag Frank Kiesewetter Armin Knauf Dagmar Escher Hans Wallmann (Kreisrätin, Gemeinderätin) Ar ne ten e lt aum fü e sr r s d g as Ban zu G ne d – k ü Rüc rü r n e Foto: LBV Altrichter G Ahorn as B a d n d Siegfried Scherbel Roter Milan Ute Dittmann Frank Schober Bad Rodach Kein neuer Flugplatz Lautertal Neustadt b. Coburg Gabriele Jahn (Kreisrätin, Gemeinderätin) Dörfles-Esbach Bedarfsgerechtes Wohnen Roedental und Leben im Alter rüne Ba Coburg G nd Weitramsdorf das Sonnefeld Felicitas Medau Untersiemau Foto: LBV Ulmer Küchenschelle Untersiemau/Großheirath/Itzgrund Annja Ammer Dezentrale Energiever Manuela Müller sorgung in Bürgerhand Thomas Schulz Svenja Kleist Egon Helder Susanne Hecky Karl-Martin Schulz Benita Silbert-Gruber Andreas Kleist GRÜN bewegt den Kreistag Gehen Sie am 16. März GRÜN wählen. Meeder Lautertal Neustadt b. Coburg Thomas Kreisler Dr. Marten Schrievers Martin Hein Heidrun Frenkler Florian Bär Gertrud Schrievers Martin Frenkler Ar ne ten e lt aum fü e sr r s d g as Ban zu G ne d – k ü Rüc rü r n G e as B d a n Foto: LBV Schönecker d Rödental Kein unnötiger Grünspecht Matthias Stein Landschaftsverbrauch Jana Günther Bad Rodach Kein neuer Flugplatz Hartmut Schmidt Edeltraud Bayer Lautertal Birgit Engels Neustadt b. Coburg Stefan Handke Gert Holland Ursula Kürzendörfer Ulrich Leicht (Kreisrat, Stadtrat) Dörfles-Esbach Roedental Sabine Krämer Tobias Faber Dr. -

Landratsamt Coburg

Landratsamt Coburg Landratsamt Coburg, Postfach 23 54, 96412 Coburg Ihre Zeichen Bitte bei Antwort angeben Sachbearbeiter/in Telefon Telefax Raum Nr. Coburg Ihre Nachricht vom Unser Zeichen E-Mail-Adresse 09561 514 - 09561 514 - 89 Dennis Flach 3113 3113 113 29.04.2020 [email protected] Jährlicher Gesamtbericht nach Artikel 7 Absatz 1 der Verordnung (EG) Nr. 1370/2007 über öffentliche Personenverkehrsdienste auf Schiene und Straße für den Landkreis Coburg für das Jahr 2019 Der Landkreis Coburg bildet mit der kreisfreien Stadt Coburg einen gemeinsamen Nahverkehrsraum. Zur Sicherstellung des Angebots im straßengebundenen öffentlichen Verkehr hat der Landkreis Coburg die Leistungen in zwei Losen zum 01.09.2016 für einen Zeitraum von 10 Jahren ausgeschrieben. Den Zuschlag erhielt die DB Frankenbus GmbH (OVF GmbH). Die OVF GmbH erbringt einen Teil der Leistungen durch Subunternehmen. Außerdem hat der Landkreis Coburg einen Vertrag mit dem Landkreis Hildburghausen zur Erbringung einer landkreisüberschreitenden Linie abgeschlossen. Die Zuschüsse tragen beide Landkreise entsprechend der auf dem jeweiligen Landkreisgebiet gefahrenen Fahrplankilometer. Folgende Leistungen sind zur Sicherstellung einer Versorgung der Landkreisbevölkerung mit Leistungen des straßengebundenen Öffentlichen Verkehrs erbracht worden: Betriebsleistung (Fahrplankilometer 2019): 1.038.861 km im regionalen Busverkehr und 32.948 km im Rufbusverkehr sowie 41.659 Km über Zu- und Abbestellungen im Rahmen des Verkehrsvertrages. Außerdem 25.764 Km (2018) zwischen Bad Rodach -

LANDKREIS COBURG COL3-1 Seite 17 Günther Knauer Führt Die „88Er“ Weiter

Mittwoch, 25. Februar 2015 LANDKREIS COBURG COL3-1 Seite 17 Günther Knauer führt die „88er“ weiter Die SSG Weidhausen hepunkt waren dabei die 26. Schieß- sportwoche und das Schützenfest. blickt auf ein erfolgreiches Günther Knauer wies darauf hin, Sportjahr zurück. Treue dass Reparaturen anstehen. Zudem Mitgliederdes Vereins muss in den nächsten Jahren die Schießanlage erneuert werden.Ziel erhalten Auszeichnungen. mussesnach seinen Worten sein, Belohnung für gute Leistungen Einnahmenzusteigern und die Be- Weidhausen –Die Scharfschützen- triebskosten zu senken. Die Mit- gesellschaft 1888 Weidhausen wird gliedsbeiträge bleiben nach der 2013 Der AMC „Hohe Aßlitz“ weiterhin von GüntherKnauer ge- erfolgten Erhöhung unverändert. führt, der bereits seit 29 Jahren als 1. DieNeuwahlen: Vorsitzender ehrtseine erfolgreichen Vorsitzender fungiert und insgesamt Günther Knauer,Schatzmeister Mitglieder und würdigt 39 Jahre der Vorstandschaft ange- KlausKnauer,2.Schatzmeisterin Me- langjährigeTreue. Der hört.Bei den Neuwahlen erhielt er lanie Wagner (neu), Schriftführerin erneut das uneingeschränkte Ver- Karin Geyer (neu), ihre Stellvertrete- Schwerpunkt des Vereins trauen der Mitglieder ausgespro- rinMartina König-Friedrich (neu), liegt auf der Jugendarbeit. chen.Insgesamt wurde die Füh- SchützenmeisterBernd Schneider rungsriege durch mehrere Neubeset- (neu), Jugendleiter Markus Eber Gestungshausen –Bei der Hauptver- zungen verjüngt. Günther Knauer (neu), 2. Jugendleiter FrankRein- sammlung desAMC „Hohe Aßlitz“ zeigte sich erfreut, dass sich so viele -

Unsere Wirtschaft WIRTSCHAFTSMAGAZIN DER IHK ZU COBURG AUSGABE 1-2/2008

Unsere Wirtschaft WIRTSCHAFTSMAGAZIN DER IHK ZU COBURG AUSGABE 1-2/2008 REGION Seite 16 imm cologne Köln: Coburger Möbel- hersteller auf der internationalen Einrichtungsmesse STANDORT Seite 18 Industrieausschuss neu konstruiert AUSBILDUNG Seite 25 Jahresthema 2008: Wirtschaft bildet unsere Zukunft INNOVATION Seite 34 Regionalcluster Automotive 2 Tagesseminare Februar / März 2008 FEBRUAR 2008 11. u. 12.02 Einführung von Controlling in Klein- und Mittelbetrieben 12.02. Kundenrückgewinnung und Neuwerbung 13.02. Umgangsformen für Azubis 14.02. Reklamationen oder Beschwerden positiv erledigen 14.02. Vorgesetzte führen Mitarbeitergespräche – Teil 1 15.02. Zeitmanagement – Die Organisation der eigenen Arbeit 15.02. Korrespondenz mit Pfiff 20. bis 22.02. Basiswissen: Lohn- und Gehaltsabrechnung (Kompaktseminar) – mit allen Änderungen für das Jahr 2008 25.02. Automatisiertes Mahnwesen und Zwangsvollstreckung 26.02. Rede- und Gesprächssituationen überzeugend und selbstsicher meistern – angewandte Rhetorik 29.02. Stress-Balance: Befreien Sie sich vom Alltagsstress MÄRZ 2008 04.03. Technik erfolgreich betreuen: Instandhaltung kostengünstig entwickeln 05.03. Mit überzeugenden Texten punkten 05.03. Workshop – Abschreibung 06. und 07.03. Buchführung Crash-Kurs 06. und 07.03. Erfolgreiche Preisverhandlung – Profiwerkzeuge der Einkäufer 10.03. Produktpiraterie – gewerblicher Rechtsschutz 05.03. Mit überzeugenden Texten punkten Auskunft und Infomaterial: Weitere Auskünfte und detailliertes Informationsmaterial erhalten Interessenten von der IHK zu Coburg, 96450 Coburg, Schloßplatz 5, Telefon (09561) 7426 -23 -24 -25, Fax (09561) 7426 -15, E-MAIL [email protected] Unsere Wirtschaft 01-02/2008 EDITORIAL ■ 3 Die laufende Abnahme der Einwohnerzahl ist eine unmittelbare Folge des stetigen Rückgangs von Arbeits- und Ausbildungsplätzen im Coburger Raum. Die von manchen Politikern angeführte demographische Entwick- lung ist keineswegs die Ursache hierfür, denn der bundesweite Geburten- rückgang gilt auch für die Regionen, die durch das Entstehen neuer Ar- beitsplätze ständig wachsen. -

Coburger Amtsblatt Nachrichtenblatt Amtlicher Dienststellen Der Stadt Coburg Und Des Landkreises Coburg

Coburger Amtsblatt Nachrichtenblatt amtlicher Dienststellen der Stadt Coburg und des Landkreises Coburg Freitag, 28. November 2014 67. Jahrgang - Nr. 44 Inhaltsverzeichnis Geltungsbereiches im Maßstab 1 : 1.000 ist Bestandteil des Beschlusses. Stadt Coburg Ziel des Bebauungsplanes Nr. 101 18 a 3/5 ist es Festset- Amtliche Bekanntmachung des Beschlusses über die Auf- zungen zu treffen, die das Gebiet auch im 21. Jahrtausend stellung des Bebauungsplanes Nr. 101 18 a 3/5 für das ordnen und leiten. Gebiet „Seidmannsdorfer Hang“ zwischen Seidmannsdor- fer Straße und Dr.-Walter-Langer-Straße; Vereinfachtes Im Zuge dieses Verfahrens sollen die Festsetzungen des Verfahren nach § 13 BauGB Bebauungsplanes Nr. 101 18 a 3/1 vom 10.04.1974 für das Gebiet Seidmannsdorfer Hang mit eingezeichneten Aufla- Amtliche Bekanntmachung des Beschlusses über die Auf- gen der Regierung von Oberfranken und des Bebauungs- stellung des Vorhaben- und Erschließungsplanes Nr. 3/6 planes Nr. 101 18 a 3/3 vom 14.03.1984 für das Gebiet für das Gebiet „Brauhof“; nördlich Riemenschneider Weg (Ost) und Lucas-Cranach- - Bebauungsplan der Innenentwicklung nach § 13 a Weg zur vereinfachten Änderung des Bebauungsplanes BauGB Nr. 101 18 a 3/1 für das Gebiet „Seidmannsdorfer Hang“ aufgehoben werden. Öffentliche Ausschreibung nach VOB/A Der Bebauungsplan Nr. 101 18 a 3/5 wird im vereinfach- Die SÜC passt die allgemeinen Tarife in der Wasserversor- ten Verfahren nach § 13 BauGB aufgestellt. gung ab 1. Januar 2015 an Im vereinfachten Verfahren nach § 13 BauGB wird nach § Allgemeine Tarifpreise Wasser, gültig ab 1. Januar 2015 13 Abs. 2 und 3 Satz 1 BauGB - von der frühzeitigen Unterrichtung und Erörterung Bildung der besonderen Arbeitsgemeinschaft nach § 3 Abs. -

Coburger Amtsblatt Nr

CCoobbuurrggeerr AAmmttssbbllaatttt Nachrichtenblatt amtlicher Dienststellen der Stadt Coburg und des Landkreises Coburg Freitag, 12.07.2019 Seite 53 72. Jahrgang – Nr. 24 Inhaltsverzeichnis Aus Gründen der Übersichtlichkeit wird die Zweckver- einbarung in Gänze abgedruckt: Stadt Coburg Zur Bildung der besonderen Arbeitsgemeinschaft Ladenschlussgesetz; „INTERKOMMUNAL. INTEGRIERT. STARK. Ersuchen der Stadt Coburg um eine Ausnahmebwilli- Auf kurzen Wegen qualitätvoll wohnen, wirtschaften gung nach § 23 Abs. 1 LadSchlG aus Anlass der „Win- und arbeiten“ terzaubernacht“ am Samstag, 30.11.2019 schließen Veröffentlichung von redaktionellen Veränderungen 1. die Gemeinde Ahorn der Zweckvereinbarung IRE vertreten durch den 1. Bürgermeister 2. die Stadt Bad Rodach Landkreis Coburg vertreten durch den 1. Bürgermeister 3. die Stadt Coburg Bekanntmachung der Haushaltssatzung des Schulver- vertreten durch den Oberbürgermeister bandes Mittelschule Sonnefeld (Landkreis Coburg) für 4. die Gemeinde Ebersdorf bei Coburg das Haushaltsjahr 2019 vertreten durch den 1. Bürgermeister 5. die Gemeinde Dörfles-Esbach Beteiligungsbericht 2017 des Landkreises Coburg vertreten durch den 1. Bürgermeister 6. die Gemeinde Großheirath vertreten durch den 1. Bürgermeister Einwohnerzahlen Landkreis Coburg 7. die Gemeinde Itzgrund Stand Dezember 2018 vertreten durch den 1. Bürgermeister 8. die Gemeinde Lautertal vertreten durch den 1. Bürgermeister Stadt Coburg 9. die Gemeinde Meeder vertreten durch den 1. Bürgermeister Ladenschlussgesetz; 10. die Stadt Neustadt bei Coburg Ersuchen der Stadt Coburg um eine Ausnahmeb- vertreten durch den Oberbürgermeister willigung nach § 23 Abs. 1 LadSchlG aus Anlass 11. die Stadt Rödental der „Winterzaubernacht“ am Samstag, vertreten durch den 1. Bürgermeister 30.11.2019 12. die Stadt Seßlach Mit Schreiben vom 05.07.2019 hat die Regierung von vertreten durch den 1. Bürgermeister Oberfranken, Bayreuth folgenden Bescheid erlassen: 13. -

Pfarrbrief 2017

Nachrichten der Pfarrei St. Otto Ebersdorf Weihnachten 2017 Bild: Martha Gahbauer In: Pfarrbriefservice.de Es gibt keine größere Kraft als die Liebe Sie überwindet den Hass wie das Licht die Finsternis. Martin Luther King Ihnen allen eine gesegnete Weihnacht! Seite 2 Pfa rrbrief 2017 St. Otto Ebersdorf Vorwort Pfarrbrief 2017 Eine Weihnachtsgeschichte erzählt von einem Engel, der bei uns die Ankunft des göttlichen Kindes verkünden sollte. Als er die hellerleuchtete Stadt sah, staunte er: So viele glitzernde Lichter-Sterne! Dazu die Musik über das göttliche Kind aus allen Ecken und Häusern, er traute seinen Ohren kaum. Der Duft nach Mandeln, Anis und Zuckerwatte erfüllte die Luft. „Oh, ich komme zu spät“ dachte er, „sie wissen es schon, sie feiern schon, sie sind schon unterwegs zur Krippe im Stall.“ Erst als er sah, wie Männer und Frauen, ohne zu singen, an ihm vorbeihasteten, wurde er aufmerksam. „Ihr Mund ist stumm, ihre Hände sind voller Taschen und Tüten, und sie schauen suchenden Auges umher, als hätten sie etwas vergessen“, sagte er leise. Da kam ein kleines Mädchen zu ihm, zeigte ihm eine große Tüte und sagte: „Habe ich vom Weihnachtsmann, geh zu ihm, der gibt dir auch eine.“ Der Engel wollte gerade seinen Mund öffnen, da hörte er eine Frau rufen: „Suse, steh nicht herum, wir müssen noch ein Geschenk für Oma kaufen. Komm, gleich schließen die Geschäfte.“ Weg war die Kleine. Nach und nach wurden die Straßen menschenleer. Nur die Lichter leuchteten, und der Engel stand noch immer unter dem Baum auf dem Markplatz. „Was soll ich tun? Sie feiern schon!“ sagte er leise vor sich hin. -

Sport Im Landkreis Coburg Sport- Und Schützenvereine Stellen Sich Vor! 3 Grusswort

landratsamt coburg Sport im Landkreis Coburg Sport- und Schützenvereine stellen sich vor! 3 Grusswort Liebe Sportfreunde, liebe Bürgerinnen, liebe Bürger, Sport hat in der Region Coburg schon seit jeher einen hohen Stellenwert. Damit tragen gerade die Sportvereine einen großen Teil zum Zusammenhalt in unserer Gesellschaft bei. Besonders stolz bin ich auf die Breite, die unsere Region im Bereich „Sport“ zu bieten hat. Aus diesem Grund ist es wichtig, dass wir als Landkreis Coburg den Vereinen gute Rahmenbedingungen bieten, um die Vielfalt des Angebots und dessen Nähe zu den Menschen vor Ort zu erhalten. An der Oberfranken-Ausstellung 2013 verschaffen wir dem Thema „Sport und Gesundheit“ am Stand des Landkreises besondere Aufmerksamkeit. Der Messestand bietet Gelegenheit, dieses Spek- trum darzustellen. Gleichzeitig sollen alle Altersgruppen motiviert werden, sich sportlich zu betätigen. Ein sehr guter Weg ist, dies über und mit einem Sportverein als Partner zu tun. Dazu ist die Broschüre „Sport im Landkreis Coburg – Sport- und Schützen- vereine stellen sich vor!“ entstanden. Sie ist eine gute und umfas- sende Orientierungshilfe. Sie soll den Weg durch die vielfältige Vereinslandschaft im Landkreis Coburg aufzeigen und den Eintritt ins aktive Vereinsleben erleichtern. Ich danke allen Sportlern und den ehrenamtlichen Funktionären, die exzellente Arbeit leisten und unsere Region, über die Land- kreisgrenzen hinaus, hervorragend repräsentieren. Mein Dank gilt auch Peter und Jürgen Rückert, die bei der Erstel- lung dieser Broschüre tatkräftig -

Landkreis Coburg - 16Th October 2017 View Online At

Landkreis Coburg - 16th October 2017 View online at http://vmkrcmar21.informatik.tu-muenchen.de/wordpress/lkcoburg/de Landkreis Coburg PDF Created on 16th October 2017 http://vmkrcmar21.informatik.tu-muenchen.de/wordpress/lkcoburg/de Page 1 Landkreis Coburg - 16th October 2017 View online at http://vmkrcmar21.informatik.tu-muenchen.de/wordpress/lkcoburg/de Table of Contents Willkommen im Landkreis Coburg ............................................................................................. 8 Willkommen im Landkreis Coburg .............................................................................................. 9 Begrüßung ................................................................................................................................ 10 Unsere Städte und Gemeinden .................................................................................................. 12 Ahorn ..................................................................................................................................... 13 Bad Rodach ............................................................................................................................. 15 Dörfles-Esbach ....................................................................................................................... 17 Ebersdorf ............................................................................................................................... 18 Großheirath ...........................................................................................................................