OVERTURE Jacob Burstein Plays for Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This Composer Profile Here

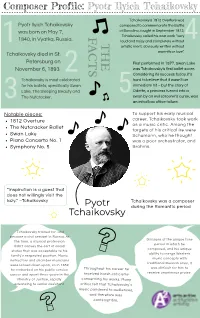

Composer Profile: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture was Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed to commemorate the Battle was born on May 7, of Borodino, fought in September 1812, F Tchaikovsky called his own work “very 1840, in Vyatka, Russia. loud and noisy and completely without THE A 4 1 artistic merit, obviously written without Tchaikovsky died in St. CTS warmth or love”. Petersburg on First performed in 1877, Swan Lake November 6, 1893. was Tchaikovsky’s first ballet score. 2 Considering its success today, it's Tchaikovsky is most celebrated hard to believe that it wasn’t an for his ballets, specifically Swan immediate hit – but the story of Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and Odette, a princess turned into a The Nutcracker. 5 swan by an evil sorcerer's curse, was 3 an initial box office failure. Notable pieces: To support his early musical 1812 Overture career, Tchaikovsky took work as a music critic. Among the The Nutcracker Ballet targets of his critical ire were Swan Lake Schumann, who he thought Piano Concerto No. 1 was a poor orchestrator, and Symphony No. 5 Brahms. “Inspiration is a guest that does not willingly visit the lazy.” –Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky was a composer I'mPy oOtrne! during the Romantic period Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky trained for, and became a civil servant in Russia. At Because of the unique time the time, a musical profession period in which he didn’t convey the sort of social composed, and his unique status that was acceptable to his ability to merge Western family’s respected position. Music music concepts with instructors and chamber musicians traditional Russian ones, it were looked down upon, so in 1859 was difficult for him to he embarked on his public service Throughout his career he receive unanimous praise. -

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto Friday, January 12, 2018 at 11 am Jayce Ogren, Guest conductor Sibelius Symphony No. 7 in C Major Tchaikovsky Concerto for Violin and Orchestra Gabriel Lefkowitz, violin Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto For Tchaikovsky and The Composers Sibelius, these works were departures from their previ- ous compositions. Both Jean Sibelius were composed in later pe- (1865—1957) riods in these composers’ lives and both were pushing Johan Christian Julius (Jean) Sibelius their comfort levels. was born on December 8, 1865 in Hämeenlinna, Finland. His father (a doctor) died when Jean For Tchaikovsky, the was three. After his father’s death, the family Violin Concerto came on had to live with a variety of relatives and it was Jean’s aunt who taught him to read music and the heels of his “year of play the piano. In his teen years, Jean learned the hell” that included his disas- violin and was a quick study. He formed a trio trous marriage. It was also with his sister older Linda (piano) and his younger brother Christian (cello) and also start- the only concerto he would ed composing, primarily for family. When Jean write for the violin. was ready to attend university, most of his fami- Jean Sibelius ly (Christian stayed behind) moved to Helsinki For Sibelius, his final where Jean enrolled in law symphony became a chal- school but also took classes at the Helsinksi Music In- stitute. Sibelius quickly became known as a skilled vio- lenge to synthesize the tra- linist as well as composer. He then spent the next few ditional symphonic form years in Berlin and Vienna gaining more experience as a composer and upon his return to Helsinki in 1892, he with a tone poem. -

PETER TCHAIKOVSKY Arr. ROBERT LONGFIELD Highlights from 1812

KJOS CONCERT BAND TRADITION OF EXCELLENCE™ GRADE 3 EXCELLENCE IN PERFORMANCE WB466F $7.00 PETER TCHAIKOVSKY arr. ROBERT LONGFIELD Highlights from 1812 Overture Correlated with TRADITION OF EXCELLENCE™ Book 3, Page 30 Correlated with TRADITION OF EXCELLENCE™ Books 1, 2, & 3 when performed as a mass band with all available parts. SAMPLE NEIL A. KJOS MUSIC COMPANY • PUBLISHER 2 SAMPLE WB466 3 About the Composer Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic era whose compositions remain popular to this day. Among his most popular works are three ballets, Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, and Te Nutcracker, six symphonies, eleven operas, the tone poems Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture, Marche Slave, Capriccio Italien, and 1812 Overture, a concerto for violin, and two concertos for piano. Tchaikovsky’s music was the frst by a Russian composer to achieve international recognition. Later in his career, Tchaikovsky made appearances around the globe as a guest conductor, including the 1891 inaugural concert of Carnegie Hall in New York City. In the late 1880s, he was awarded a lifetime pension by Emperor Alexander III of Russia. But, Tchaikovsky batled many personal crises and depression throughout his career, despite his popular successes. Nine days afer he conducted the premiere of his Sixth Symphony, “the Pathétique,” Tchaikovsky died. Te circumstances of his death are shrouded in ambiguity. Te ofcial report states that he contracted cholera from drinking contaminated river water. However, at this time in St. Petersburg, a death from cholera was practically unheard of for someone Tchaikovsky’s wealth. For this reason, many people, including members of his family, believe that his death is the result of suicide related to the depression he batled during his life. -

Super-Heroes of the Orchestra

S u p e r - Heroes of the Orchestra TEACHER GUIDE THIS BELONGS TO: _________________________ 1 Dear Teachers: The Arkansas Symphony Orchestra is presenting SUPER-HEROES OF THE SYMPHONY this year to area students. These materials will help you integrate the concert experience into the classroom curriculum. Music communicates meaning just like literature, poetry, drama and works of art. Understanding increases when two or more of these media are combined, such as illustrations in books or poetry set to music ~~ because multiple senses are engaged. ABOUT ARTS INTEGRATION: As we prepare students for college and the workforce, it is critical that students are challenged to interpret a variety of ‘text’ that includes art, music and the written word. By doing so, they acquire a deeper understanding of important information ~~ moving it from short-term to long- term memory. Music and art are important entry points into mathematical and scientific understanding. Much of the math and science we teach in school are innate to art and music. That is why early scientists and mathematicians, such as Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Pythagoras, were also artists and musicians. This Guide has included literacy, math, science and social studies lesson planning guides in these materials that are tied to grade-level specific Arkansas State Curriculum Framework Standards. These lesson planning guides are designed for the regular classroom teacher and will increase student achievement of learning standards across all disciplines. The students become engaged in real-world applications of key knowledge and skills. (These materials are not just for the Music Teacher!) ABOUT THE CONTENT: The title of this concert, SUPER-HEROES OF THE SYMPHONY, suggests a focus on musicians/instruments/real and fictional people who do great deeds to help achieve a common goal. -

The Nutcracker"

The Essentials: "The Nutcracker" Lauren LaRocca, Friday, December 13 Photo Sharen Bradford Presented by Aspen Santa Fe Ballet 2 and 7:30 p.m. Saturday, Dec. 14 1 and 5 p.m. Sunday, Dec. 15 Lensic Performing Arts Center, 211 W. San Francisco Street Tickets are $36 to $94; 505-988-1234, lensic.org The origin The origin of The Nutcracker ballet can be traced back to E.T.A. Hoffmann’s bizarre 1816 Christmas story, Nutcracker and the Mouse King (Nussknacker und Mausekönig). In it, the heroine is named Maria. (In the ballet, she’s sometimes called Maria, Marie, and the familiar Clara.) The ballet wasn’t inspired by Hoffman’s story, per se, but by an adaptation of the story written by Alexandre Dumas, The Story of a Nutcracker, in 1844. The ballet was created nearly 50 years later, debuting in 1892, with musical composition by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and choreography by Marius Petipa (when Petipa grew ill, Lev Ivanov took over and finished the piece) Composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Born in Russia in 1840, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky began studying piano at 5 and later attended the St. Petersburg Conservatory. There he learned Western methods of composition, which widened his perception of styles and allowed him to understand music cross-culturally. This training would set his work apart from other Russian composers. After graduating, he began teaching music theory at Moscow Conservatory while working on his own symphonies and ballets. He became best known for writing the 1812 Overture, as well as his Nutcracker, Swan Lake, and Sleeping Beauty ballets. -

National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine

NATIONAL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA OF UKRAINE VOLODYMYR SIRENKO, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR AND CONDUCTOR ALEXEI GRYNYUK, PIANO Saturday, March 4, 2017, at 7:30pm Foellinger Great Hall PROGRAM NATIONAL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA OF UKRAINE Volodymyr Sirenko, artistic director and conductor Theodore Kuchar, conductor laureate Yevhen Stankovych Suite from the ballet The Night Before Christmas (b. 1942) Introduction Oksan and Koval Kozachok Robert Schumann Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op. 54 (1819-1896) Allegro affettuoso; Andante grazioso; Allegro Intermezzo: Andante grazioso Allegro vivace Alexei Grynyuk, piano 20-minute intermission Antonín Dvorák Symphony No. 9 in E Minor, Op. 95, “From the New World” (1841-1904) Adagio Largo Scherzo: Molto vivace Allegro con fuoco The National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine appears by arrangement with: Columbia Artists Management LLC 5 Columbus Circle @ 1790 Broadway New York, NY 10019 www.cami.com 2 THE ACT OF GIVING OF ACT THE THANK YOU TO THE SPONSORS OF THIS PERFORMANCE Krannert Center honors the spirited generosity of these committed sponsors whose support of this performance continues to strengthen the impact of the arts in our community. CLAIR MAE & G. WILLIAM ARENDS Krannert Center honors the memory of Endowed Underwriters Clair Mae & G. William Arends. Their lasting investment in the performing arts will ensure that future generations can enjoy world-class performances such as this one. We appreciate their dedication to our community. CAROLE & JERRY RINGER Through their previous sponsorships and this year’s support, Endowed Sponsors Carole & Jerry Ringer continue to share their passion for the beauty and emotion of classical music with our community. Krannert Center is grateful for their ongoing support and dedication to the performing arts. -

Understanding Music Nineteenth-Century Music and Romanticism

N ineteenth-Century Music and Romanticism 6Jeff Kluball and Elizabeth Kramer 6.1 OBJECTIVES 1. Demonstrate knowledge of historical and cultural contexts of nineteenth- century music, including musical Romanticism and nationalism 2. Aurally identify selected genres of nineteenth century music and their associated expressive aims, uses, and styles 3. Aurally identify the music of selected composers of nineteenth century music and their associated styles 4. Explain ways in which music and other cultural forms interact in nineteenth century music in genres such as the art song, program music, opera, and musical nationalism 6.2 KEY TERMS AND INDIVIDUALS • 1848 revolutions • Exoticism • Antonín Dvořák • Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel • art song • Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy • Augmented second • Francisco de Goya • Bedřich Smetana • Franz Liszt • Beethoven • Franz Schubert • Caspar David Friedrich • Fryderyk Chopin • chamber music • Giuseppe Verdi • chromaticism • idée fixe • concerto • Johann Wolfgang von Goethe • conductor • John Philip Sousa • drone • leitmotiv • Eugène Delacroix • lied Page | 160 UNDERSTANDING MUSIC NINETEENTH-CENTURY MUSIC AND ROMANTICISM • Louis Moreau Gottschalk • soirée • Mary Shelley • sonata • mazurka • sonata form (exposition, • nationalism development, recapitulation) • opera • song cycle • program symphony • string quartet • Pyotr Tchaikovsky • strophic • Richard Wagner • symphonic poem • Robert and Clara Schumann • Symphony • Romanticism • ternary form • rubato • through-composed • salon • V.E.R.D.I. • scena ad aria (recitative, • William Wordsworth cantabile, cabaletta) 6.3 INTRODUCTION AND HISTORICAL CONTEXT This chapter considers music of the nineteenth century, a period often called the “Romantic era” in music. Romanticism might be defined as a cultural move- ment stressing emotion, imagination, and individuality. It started in literature around 1800 and then spread to art and music. -

The Impact of Russian Music in England 1893-1929

THE IMPACT OF RUSSIAN MUSIC IN ENGLAND 1893-1929 by GARETH JAMES THOMAS A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music School of Humanities The University of Birmingham March 2005 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis is an investigation into the reception of Russian music in England for the period 1893-1929 and the influence it had on English composers. Part I deals with the critical reception of Russian music in England in the cultural and political context of the period from the year of Tchaikovsky’s last successful visit to London in 1893 to the last season of Diaghilev’s Ballet russes in 1929. The broad theme examines how Russian music presented a challenge to the accepted aesthetic norms of the day and how this, combined with the contextual perceptions of Russia and Russian people, problematized the reception of Russian music, the result of which still informs some of our attitudes towards Russian composers today. Part II examines the influence that Russian music had on British composers of the period, specifically Stanford, Bantock, Vaughan Williams, Holst, Frank Bridge, Bax, Bliss and Walton. -

Tchaikovsky Nutcracker Suite / 1812 Overture / Marche Slave Mp3, Flac, Wma

Tchaikovsky Nutcracker Suite / 1812 Overture / Marche Slave mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Nutcracker Suite / 1812 Overture / Marche Slave Country: US Released: 1962 Style: Romantic MP3 version RAR size: 1910 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1462 mb WMA version RAR size: 1169 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 770 Other Formats: RA ASF MOD FLAC DTS MMF MP3 Tracklist Nutcracker Suite, Op. 71a A1.1 Overture Miniature A1.2 March A1.3 Dance Of The Sugar-Plum Fairy A1.4 Russian Dance A1.5 Arab Dance A1.6 Chinese Dance A1.7 Dance Of The Reed Flutes A1.8 Waltz Of The Flowers B1 1812 Overture, Op. 49 B2 Marche Slave, Op. 31 Credits A&R – Ethel Gabriel Composed By – Tchaikovsky* Conductor – Odd Grüner-Hegge Liner Notes – Alan Rich Orchestra – Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra* Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Tchaikovsky*, Oslo Tchaikovsky*, Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra*, Philharmonic RCA CAS 630 Odd Grüner-Hegge - CAS 630 Canada 1962 Orchestra*, Odd Camden Nutcracker Suite / 1812 Grüner-Hegge Overture / Marche Slave (LP) Tchaikovsky*, Oslo Tchaikovsky*, Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra*, Philharmonic Odd Grüner-Hegge - RCA CAL 630 CAL 630 US 1962 Orchestra*, Odd Nutcracker Suite / 1812 Camden Grüner-Hegge Overture / Marche Slave (LP, Mono) Related Music albums to Nutcracker Suite / 1812 Overture / Marche Slave by Tchaikovsky Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky / Maurice Ravel - Suite From The Ballet The Nutcracker Suite, Op. 71A/Bolero Tchaikovsky - Philharmonia Orchestra, Wolfgang Sawallisch - Swan Lake & Nutcracker Ballet Suites Grieg — Kjell Baekkelund - Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, Odd Grüner-Hegge - Piano Concerto / Music From Peer Gynt Tchaikovsky - Nutcracker Suite Tchaikovsky - The London Festival Orchestra, Robert Sharples - Tchaikovsky In Phase Four Various - This Is Stereo Leonard Bernstein, New York Philharmonic, Prokofiev, Tchaikovsky - Peter And The Wolf · Nutcracker Suite Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, The London Philharmonic Orchestra - Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker – 1812 – Francesca Da Rimini – Romeo And Juliet. -

SAN DIEGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA a JACOBS MASTERWORKS CONCERT Pinchas Zukerman, Conductor and Violin

SAN DIEGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA A JACOBS MASTERWORKS CONCERT Pinchas Zukerman, conductor and violin February 2 and 3, 2018 PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY Mélodie, No. 3 from Souvenir d’un lieu cher, Op. 42 Arr. by Glazunov Pinchas Zukerman, violin PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY Sérénade mélancolique, Op. 26 Pinchas Zukerman, violin PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY Serenade in C Major, Op. 48 Pezzo in forma di Sonatina Walzer Élégie Finale (Tema Russo) INTERMISSION FELIX MENDELSSOHN Symphony No. 4 in A Major, Op. 90: Italian Allegro vivace Andante con moto Con moto moderato Saltarello: Presto Mélodie, No. 3 from Souvenir d’un lieu cher, Op. 42 (Arr. by Glazunov) PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY Born May 7, 1840, Votkinsk Died November 6, 1893, St. Petersburg In the summer of 1877, Tchaikovsky made an ill-advised marriage. It was a disaster – it lasted only a few weeks – and the composer, near mental collapse, fled Russia. He found refuge in Switzerland, where he gradually recovered in the quiet beauty of Clarens, on the Lake of Geneva. One of his visitors there was Yosif Kotek, a violinist and one of his former students in Moscow. Together, they played music for violin and piano, and Tchaikovsky began to compose for the violin: in the spring of 1878 he wrote the Violin Concerto and a collection of three short pieces for violin and piano. He published these latter works under the name Souvenir d’un lieu cher (“Memory of a Dear Place”), a title that expresses his affection for Clarens and its calming influence. The brief Mélodie is the final piece of this set. -

Super-Heroes of the Orchestra

Design your own picture or collage of your heroes. S u p e r - Heroes of the Orchestra STUDENT JOURNAL G r a d e 3 t h r o u g h 6 THIS BELONGS TO: _________________________ CLASS: __________________________________ 1 The Layout of the Modern Symphony Orchestra There are many ways that a conductor can arrange the seating of the musicians for a particular work or concert. The above is an example of one of the common ways that the conductor places the instruments. When you go to the concert, see if the Arkansas Symphony is arranged the same as this layout. If they are not the same as this picture, which instruments are in different places? __________________________________________________________________________________ What instruments sometimes play with the orchestra and are not in this picture? __________________________________________________________________________________ What instruments usually are not included in an orchestra? __________________________________________________________________________________ There is no conductor in this picture. Where does the conductor stand? _____________ Go to www.DSOKids.com to listen to each instrument (go to Listen, then By Instrument). 2 MEET THE CONDUCTOR! Geoffrey Robson is the Conductor of the Children’s Concert, Associate Conductor of the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra and Music Director of the Arkansas Symphony Youth Orchestra. He joined the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra five years ago and plays the violin in the First Violin section. What year did he join the ASO? _________ Locate on the orchestra layout where the First Violins are seated. Mr. Robson was born in Michigan and grew up in upstate New York. He learned to play the violin when he was very young. -

Composer Biography: Pyotr Ilych Tchaikovsky

CLIBURN KIDS COMPOSER BIOGRAPHY PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY BORN: May 7, 1840 ERA/STYLE: Romantic DIED: November 6, 1893 HOMETOWN: Votkinsk, Russia Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was born in Russia in 1840. He started to study music at the age of 5 and soon revealed his amazing musical talents. Although his parents loved music, they did not expect him to have a musical career. They wanted him to become a lawyer. Tchaikovsky graduated from law school when he was 19 and went to work for the government. When he was 22 he decided to enter the St. Petersburg Conservatory where he began to study music seriously. In 1866, Tchaikovsky moved permanently to Moscow where he accepted a teaching position at the Moscow Conservatory. It was there that his first symphonies and other shorter works were created. In addition to composing and teaching, he also wrote about music and was a music critic for a Moscow paper. A wealthy widow, Mrs. Nadezhda von Meck, was especially taken with Tchaikovsky’s music. She paid him large sums of money to concentrate on composing, and he resigned from the Moscow Conservatory in October 1878. He worked for Mrs. Nadezhda von Meck for 13 years. One of his most popular works, the Fourth Symphony, was dedicated to her. Tchaikovsky also became a great conductor. After a concert tour of Europe, he visited the United States, where he conducted at the dedication of Carnegie Hall in New York City. After a successful concert tour of six American cities, he returned home to Russia to compose his famous ballet, The Nutcracker.