TCHAIKOVSKY EDITION Liner Notes and Sung Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tchaikovsky Caprice Italien - "Eugene Onegin": Introduction & Waltz and Polonaise - Theme and Variations from Suite No

Tchaikovsky Caprice Italien - "Eugene Onegin": Introduction & Waltz And Polonaise - Theme And Variations From Suite No. 3 In G mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Caprice Italien - "Eugene Onegin": Introduction & Waltz And Polonaise - Theme And Variations From Suite No. 3 In G Country: UK Released: 1961 MP3 version RAR size: 1418 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1935 mb WMA version RAR size: 1899 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 172 Other Formats: MP1 VOC ASF MOD AA AU DTS Tracklist A1 Caprice Italien, Op. 45 A2 Introduction And Waltz (From Eugene Onegin, Act 2) B1 Polonaise (From Eugene Onegin, Act 3) B2 Theme And Variations (From Suite No. 3 In G Major, Op. 55) Companies, etc. Record Company – E.M.I. Records Limited Printed By – Garrod & Lofthouse Credits Composed By – Tchaikovsky* Conductor – Lovro Von Matacic Notes Recorded in co-operation with "E. A. Teatro alla Scala, Milan" Title on Spine "Caprice Italien etc." Title on Coverfront: "In collaboazione con l'ente autonomo del Teatro alla Scala - Tchaikovsky - Caprice Italien - Introduction And Waltz from "Eugene Onegin" - Polonaise from "Eugene Onegin" - Theme And Variations from Suite No.3 in G Major" Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Tchaikovsky*, The Orchestra Of La Scala, Tchaikovsky*, The Milan*, Lovro Von Matacic Orchestra Of La SAX 2418, - Caprice Italien - "Eugene Columbia, SAX 2418, Scala, Milan*, UK 1961 33CX 1772 Onegin": Introduction & Columbia 33CX 1772 Lovro Von Waltz And Polonaise - Matacic Theme And Variations From Suite No. 3 In G (LP) Related Music albums to Caprice Italien - "Eugene Onegin": Introduction & Waltz And Polonaise - Theme And Variations From Suite No. -

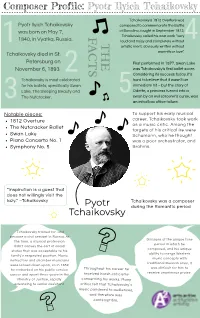

Download This Composer Profile Here

Composer Profile: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture was Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed to commemorate the Battle was born on May 7, of Borodino, fought in September 1812, F Tchaikovsky called his own work “very 1840, in Vyatka, Russia. loud and noisy and completely without THE A 4 1 artistic merit, obviously written without Tchaikovsky died in St. CTS warmth or love”. Petersburg on First performed in 1877, Swan Lake November 6, 1893. was Tchaikovsky’s first ballet score. 2 Considering its success today, it's Tchaikovsky is most celebrated hard to believe that it wasn’t an for his ballets, specifically Swan immediate hit – but the story of Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and Odette, a princess turned into a The Nutcracker. 5 swan by an evil sorcerer's curse, was 3 an initial box office failure. Notable pieces: To support his early musical 1812 Overture career, Tchaikovsky took work as a music critic. Among the The Nutcracker Ballet targets of his critical ire were Swan Lake Schumann, who he thought Piano Concerto No. 1 was a poor orchestrator, and Symphony No. 5 Brahms. “Inspiration is a guest that does not willingly visit the lazy.” –Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky was a composer I'mPy oOtrne! during the Romantic period Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky trained for, and became a civil servant in Russia. At Because of the unique time the time, a musical profession period in which he didn’t convey the sort of social composed, and his unique status that was acceptable to his ability to merge Western family’s respected position. Music music concepts with instructors and chamber musicians traditional Russian ones, it were looked down upon, so in 1859 was difficult for him to he embarked on his public service Throughout his career he receive unanimous praise. -

Understanding the Roots of Collectivism and Individualism in Russia Through an Exploration of Selected Russian Literature - and - Spiritual Exercises Through Art

Understanding the Roots of Collectivism and Individualism in Russia through an Exploration of Selected Russian Literature - and - Spiritual Exercises through Art. Understanding Reverse Perspective in Old Russian Iconography by Ihar Maslenikau B.A., Minsk, 1991 Extended Essays Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Liberal Studies Program Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Ihar Maslenikau 2015 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2015 Approval Name: Ihar Maslenikau Degree: Master of Arts Title: Understanding the Roots of Collectivism and Individualism in Russia through an Exploration of Selected Russian Literature - and - Spiritual Exercises through Art. Understanding of Reverse Perspective in Old Russian Iconography Examining Committee: Chair: Gary McCarron Associate Professor, Dept. of Communication Graduate Chair, Graduate Liberal Studies Program Jerry Zaslove Senior Supervisor Professor Emeritus Humanities and English Heesoon Bai Supervisor Professor Faculty of Education Paul Crowe External Examiner Associate Professor Humanities and Asia-Canada Program Date Defended/Approved: November 25, 2015 ii Abstract The first essay is a sustained reflection on and response to the question of why the notion of collectivism and collective coexistence has been so deeply entrenched in the Russian society and in the Russian psyche and is still pervasive in today's Russia, a quarter of a century after the fall of communism. It examines the development of ideas of collectivism and individualism in Russian society, focusing on the cultural aspects based on the examples of selected works from Russian literature. It also searches for the answers in the philosophical works of Vladimir Solovyov, Nicolas Berdyaev and Vladimir Lossky. -

The AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS’ ASSOCIATION JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2002 VOLUME 39, NUMBER 1 Mooluriil's MAGAZINE

The AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS’ ASSOCIATION JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2002 VOLUME 39, NUMBER 1 MoOLURIil'S MAGAZINE The Self-Playing Piano is It People who have watched these things closely have noticed that popular favor is toward the self-playing piano. A complete piano which will ornament your drawing-room, which can be played in the ordinary way by human fingers, or which. -'\ can be played by a piano player concealed inside the case, is the most popular musical instrument in the world to-day. The Harmonist Self-Playing Piano is the instrument which best meets these condi tions. The piano itself is perfect in tone and workmanship. The piano player at tachment is inside, is operated by perforated music, adds nothing to the size of the piano. takes up no room whatever, is always ready, is never in the way. We want everyone who is thinking of buying a piano to consider the great advan tage of getting a Harmonist, which combines the piano and the piano player both. It costs but little more than a good piano. but it is ten times as useful and a hundred times as entertaining. Write for particulars. ROTH ~ENGELHARDT Proprietors Peerless Piano Player Co. Windsor Aroade. Fifth Ave.. New York Please mention McClure·s when you write to ad"crtiscrt. 77 THE AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS' ASSOCIATION Published by the Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors’ Association, a non-profit, tax exempt group devoted to the restoration, distribution and enjoyment of musical instruments using perforated paper music rolls and perforated music books. -

Elizabeth Joy Roe, Piano

The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts STEPHEN A. SCHWARZMAN , Chairman MICHAEL M. KAISER , President TERRACE THEATER Saturday Evening, October 31, 2009, at 7:30 presents Elizabeth Joy Roe, Piano BACH/SILOTI Prelude in B minor CORIGLIANO Etude Fantasy (1976) For the Left Hand Alone Legato Fifths to Thirds Ornaments Melody CHOPIN Nocturne in C-sharp minor, Op. 27, No. 1 WAGNER/LISZT Isoldens Liebestod RAVEL La Valse Intermission MUSSORGSKY Pictures at an Exhibition Promenade The Gnome Promenade The Old Castle Promenade Tuileries The Ox-Cart Promenade Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle Promenade The Market at Limoges (The Great News) The Catacombs With the Dead in a Dead Language Baba-Yaga’s Hut The Great Gate of Kiev Elizabeth Joy Roe is a Steinway Artist Patrons are requested to turn off pagers, cellular phones, and signal watches during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. Notes on the Program By Elizabeth Joy Roe Prelude in B minor Liszt and Debussy. Yet Corigliano’s etudes JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH ( 1685 –1750) are distinctive in their effective synthesis of trans. ALEXANDER SILOTI (1863 –1945) stark dissonance and an expressive landscape grounded in Romanticism. Alexander Siloti, the legendary Russian pianist, The interval of a second—and its inversion composer, conductor, teacher, and impresario, and expansion to sevenths and ninths—is the was the bearer of an impressive musical lineage. connective thread between the etudes; its per - He studied with Franz Liszt and was the cousin mutations supply the foundation for the work’s and mentor of Sergei Rachmaninoff. -

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ. -

Tchaikovsky.Pdf

Tchaikovsky CD 1 1 Orchestrion It wasn’t unusual, in the middle of the 19th century, to hear sounds like that coming from the drawing rooms of comfortable, middle-class families. The Orchestrion, one of the first and grandest of mass-produced mechanical music-makers, was one of the precursors of the 20th century gramophone. It brought music into homes where otherwise it might never have been heard, except through the stumbling fingers of children, enduring, or in some cases actually enjoying, their obligatory half-hour of practice time. In most families the Orchestrion was a source of pleasure. But in one Russian household, it seems to have been rather more. It afforded a small boy named Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky some of his earliest glimpses into a world, and a language, which was to become (in more senses then one), his lifeline. One evening his French governess, Fanny Dürbach, went into the nursery and found the tiny child sitting up in bed, crying. ‘What’s the matter?’ she asked – and his answer surprised her. ‘This music’ he wailed, ‘this music!’ She listened. The house was quiet. ‘No. It’s here,’ cried the boy – he pointed to his head. ‘It’s here, and I can’t make it go away. It won’t leave me.’ And of course it never did. ‘His sensitivity knew no bounds and so one had to deal with him very carefully. Every little trifle could upset or wound him. He was a child of glass. As for reproofs and admonitions (with him there could be no question of punishments), what would have been water off a duck’s back to other children affected him deeply, and if the degree of severity was increased only the slightest, it would upset him alarmingly.’ Despite his outwardly happy appearance, peace of mind is something Tchaikovsky rarely knew, from childhood to his dying day. -

Mockings of the Master Illusionist

Books does not instruct. It is true, of course, tliat "resistance" in a novelist, if unac Mockings of the Master Illusionist companied by an instinct for true values, can be simply a show-biz number (mor Tyrants Destroyed and sian-language past when he went as "V. ally. Mailer and Updike weigh roughly Other Stories Sirin"; and lo, a foreword apprises us the same). But time and again in Up by Vladimir Nabokov that his oeuvre has been accorded a full- dike's stories, you feel an aptitude for McGraw-Hill, 288 pp., $7.95 dress bibliography and reminds us (cryp something better than stylized No! in tically) that he also wrote Lolita. The thunder, a capacity for a more active and Reviewed by Hugh Kenner bang-you're-dead reviewer will lower his earnest address to experience, an interest cocked index and think twice before pro in playing in other than the sad-song ike Oscar Wilde and Charles Kinbote, nouncing stories so sponsored dismay keys, even a trace of moral authority. LI Nabokov plays—has been playing ingly empty, especially as Nabokov has An example: Toward the end of the now for many decades—a game to which more than once slipped in ahead of him, book at hand, Ms. Prynne, keeper of the self-appreciation is intrinsic. His invented anticipating doubts but leaving them rest home. Christian believer, woman of selves even appreciate one another. John equivocal. conscience, commits an exemplary piece Ray, Jr., Ph.D., in his foreword to Lolita, For instance, the fourth story, of kindness in the public ways, when con tells us how to admire what Humbert "Music," is called in its headnote "a fronted by a drunken Indian. -

|||GET||| the Stories of Vladimir Nabokov 1St Edition

THE STORIES OF VLADIMIR NABOKOV 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Dmitri Nabokov | 9780679729976 | | | | | [PDF] The Stories of Vladimir Nabokov Book by Vladimir Nabokov Free Download (685 pages) Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. At night one perceives with a special intensity the immobility of objects—the lamp, the furniture, the framed photographs on one's desk. It's a powerful, moving glimpse into the life of an immigrant couple visit their son in a mental asylum on The Stories of Vladimir Nabokov 1st edition birthday. Very Good. It's similar in my aesthetic tastes, too. Dec 15, Myles rated it really liked it Shelves: short- stories. And beyond the bend, above the sidewalk—how unexpectedly! Payment details. A glass column, full of liquid yellow light, stands at the streetcar stop, and, for some reason, I get such a blissful, melancholy sensation when, late at night, its wheels screeching around the bend, a tram hurtles past, empty. The opening paragraph in Part 3 wonderfully sets the scene: " On the browner and wetter part of the plage, that part which at low tide yielded the best mud for castles, I found myself digging, one day, side by side with a little French girl called Colette. All orders ship within two business days. The first third took me a long time because the stories in this part are very short and each one is l I know and love Nabokov. I think I'd much prefer having single collections of short stories, which are more hit-or-miss for me in general, as a reader. This collection is a must for those who adore Nabokov, but also an interesting introduction to The Stories of Vladimir Nabokov 1st edition for those whose only exposure may be "Lolita'. -

RUSS 385: Russian Drama Lyudmila Parts 1 Fall 2021

RUSS 385: Russian Drama Lyudmila Parts 1 Fall 2021 RUSS 385 Prof. Lyudmila Parts 688 Sherbrooke, #332 email: [email protected] T/TH 1:05-2:25. Notice different classrooms: Tuesday SH 688, # 491 Thursday SH 688, # 391 Office hours: Tuesday 2:30-3:30 and by appointment on Zoom Russian Drama from Pushkin to Chekhov. Major topics: • The development of Russian Drama in the 19th century. Formation of dramatic canon. • Theories of drama and theater. Dramatic conventions and radical experiments with the form. • European influence and Russian context. Texts on MyCourses to be printed out by you: 1. Alexander Griboedov, The Trouble with Reason 2-5. Alexander Pushkin, Boris Godunov; Little Tragedies (3): Miserly Knight, Mozart and Salieri, The Stone Guest 6. Mikhail Lermontov, Masquerade 7. Nikolai Gogol, The Inspector General 8. Ivan Turgenev, A Month in the Country 9-10. Alexander Ostrovsky, The Storm; The Dowerless Girl 11. Maxim Gorky, The Lower Depth 12. Leo Tolstoy, The Fruits of Enlightenment 13-14. Anton Chekhov, The Seagull; Three Sisters 15. Mikhail Bulgakov, The Days of the Turbins. Requirements: Short paper (3-4 pages) - a close reading of a passage or an exploration of a theme. Topics will be posted in advance on MyCourses. Final paper (5-6 pages) - on the topic dealing with a period, author, work, theme, cultural problem, and/or theoretical issue discussed in the course. Group projects (two): I will divide the class into small groups and assign the topics for presentation and plays for performance. See MyCourses for details. For both projects, each student submits individual report and receives an individual grade. -

History and Drama: the Pan-European Tradition Abstract Booklet

History and Drama: The Pan-European Tradition Abstract Booklet International Conference, October 26-27, 2016 organised by Tatiana Korneeva, Jaša Drnovšek and Joachim Küpper DramaNet – Early Modern European Drama and the Cultural Net Freie Universität Berlin The DramaNet project is funded by the European Research Council Grant agreement no. 246603 Thursday, October 27, 2016 10.15-12.10 Panel III: Theoretical Perspectives on History and Drama History and Drama: The Pan-European Tradition Chair: Gaia Gubbini 10.15-10.50 DS Mayfield, “The Economy of Rhetorical Ventriloquism” Conference Programme 10.50-11.25 Gautam Chakrabarti, “The Cultural Dynamics of Difference: Towards a Histoire Croisée of Asian Literary Theory” 11.25-12.00 Elena Penskaya, “Farce Comedies by Henry Fielding (The Tragedy of Tragedies; or, the Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great) and Wednesday, October 26, 2016 Ludwig Tieck (Puss in Boots, etc.) as Historical Travesty” 12.00-13.45 Lunch 14:00-14:30 Registration 14.30-14.45 Welcome and Opening Remarks 13.45-15.55 Panel IV: Mapping Dramatic Histories Chair: Jan Mosch 14.45-16.30 Panel I: Historiography and Drama 13.45-14.20 Natalia Sarana, “The Drama of ‘Bildung’: Approaches to the Study Chair: DS Mayfield of Alexander Ostrovsky’s Plays” 14.45-15.20 Joachim Küpper, “Literature and Historiography in Aristotle” 14.20-15.55 Olga Kouptsova, “Ostrovsky's Experience of the Creation of the 15.20-15.55 Gaia Gubbini, “King Arthur: History or Fiction? Investigations in European Theatrical Canon and Russian Stage Practice: Personal French Medieval Literature” Preferences and General Trends” 15.55-16.30 Pavel Sokolov and Julia Ivanova “The Tacitist Background of Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft’s Drama” 15. -

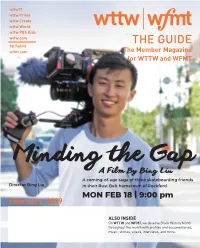

Inside the Guide the Guide

wttw11 wttw Prime wttw Create wttw World wttw PBS Kids wttw.com THE GUIDE 98.7wfmt wfmt.com The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT A coming-of-age saga of three skateboarding friends Director Bing Liu in their Rust Belt hometown of Rockford. MON FEB 18 | 9:00 pm February 2019 ALSO INSIDE On WTTW and WFMT, we observe Black History Month throughout the month with profiles and documentaries, music, stories, videos, interviews, and more. From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT Dear Member, Renée Crown Public Media Center 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Greetings from WTTW and WFMT. This month, we are excited to bring you Chicago, Illinois 60625 the acclaimed documentary about the life of a public media treasure and icon – Mister Fred Rogers. Won’t You Be My Neighbor? premieres on WTTW11 on Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 February 9. Join us for an in-depth and entertaining look at the life of a visionary Member and Viewer Services who fostered compassion and curiosity in generations of children and families. (773) 509-1111 x 6 February is also Black History Month, and we will celebrate it on WTTW11, Websites WTTW Prime, and wttw.com. You’ll find highlights of this special programming wttw.com on page 7 and at wttw.com/blackhistorymonth. Don’t miss new Finding Your wfmt.com Roots specials, in which Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores race, family, and Publisher identity in today’s America by uncovering the genealogy of Michael Strahan, Anne Gleason S. Epatha Merkerson, and many more.