The Nutcracker"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Schooltime Performance Series Nutcracker

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the nutcracker National Ballet Theatre of Odessa about the meet the cultural A short history on ballet and promoting performance composer connections diversity in the dance form Prepare to be dazzled and enchanted by The Nutcracker, a Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) was an important Russian timeless and beloved ballet performance that is perfect for children composer who is famous for his romantic, melodic and emotional Ballet’s roots In the 20th century, ballet continued to evolve with the emergence of of all ages and adults who have grown up watching it during the musical works that are still popular and performed to this day. He Ballet has its roots in Italian Renaissance court pageantry. During notable figures, such as Vaslav Nijinsky, a male ballet dancer virtuoso winter holiday season. is known for his masterful, enchanting compositions for classical weddings, female dancers would dress in lavish gowns that reached their who could dance en pointe, a rare skill among male dancers, and George Balanchine, a giant in ballet choreography in America. The Nutcracker, held all over the world, varies from one production ballet, such as The Nutcracker, Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty. ankles and dance before a crowd of aristocrats, wealthy merchants, and company to another with different names for the protagonists, Growing up, he was clearly musically gifted; Tchaikovsky politically-connected financiers, such as the Medici family of Florence. Today, ballet has morphed to include many different elements, besides traditional and classical. Contemporary ballet is based on choreography, and even new musical additions in some versions. -

Download This Composer Profile Here

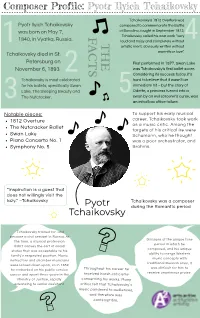

Composer Profile: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture was Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed to commemorate the Battle was born on May 7, of Borodino, fought in September 1812, F Tchaikovsky called his own work “very 1840, in Vyatka, Russia. loud and noisy and completely without THE A 4 1 artistic merit, obviously written without Tchaikovsky died in St. CTS warmth or love”. Petersburg on First performed in 1877, Swan Lake November 6, 1893. was Tchaikovsky’s first ballet score. 2 Considering its success today, it's Tchaikovsky is most celebrated hard to believe that it wasn’t an for his ballets, specifically Swan immediate hit – but the story of Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and Odette, a princess turned into a The Nutcracker. 5 swan by an evil sorcerer's curse, was 3 an initial box office failure. Notable pieces: To support his early musical 1812 Overture career, Tchaikovsky took work as a music critic. Among the The Nutcracker Ballet targets of his critical ire were Swan Lake Schumann, who he thought Piano Concerto No. 1 was a poor orchestrator, and Symphony No. 5 Brahms. “Inspiration is a guest that does not willingly visit the lazy.” –Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky was a composer I'mPy oOtrne! during the Romantic period Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky trained for, and became a civil servant in Russia. At Because of the unique time the time, a musical profession period in which he didn’t convey the sort of social composed, and his unique status that was acceptable to his ability to merge Western family’s respected position. Music music concepts with instructors and chamber musicians traditional Russian ones, it were looked down upon, so in 1859 was difficult for him to he embarked on his public service Throughout his career he receive unanimous praise. -

A SEASON of Dance Has Always Been About Togetherness

THE SEASON TICKET HOLDER ADVANTAGE — SPECIAL PERKS, JUST FOR YOU JULIE KENT, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR 2020/21 A SEASON OF Dance has always been about togetherness. Now more than ever, we cannot“ wait to share our art with you. – Julie Kent A SEASON OF BEAUTY DELIGHT WONDER NEXTsteps A NIGHT OF RATMANSKY New works by Silas Farley, Dana Genshaft, Fresh, forward works by Alexei Ratmansky and Stanton Welch MARCH 3 – 7, 2021 SEPTEMBER 30 – OCTOBER 4, 2020 The Kennedy Center, Eisenhower Theater The Harman Center for the Arts, Shakespeare Theatre The Washington Ballet is thrilled to present an evening of works The Washington Ballet continues to champion the by Alexei Ratmansky, American Ballet Theatre’s prolific artist-in- advancement and evolution of dance in the 21st century. residence. Known for his musicality, energy, and classicism, the NEXTsteps, The Washington Ballet’s 2020/21 season opener, renowned choreographer is defining what classical ballet looks brings fresh, new ballets created on TWB dancers to the like in the 21st century. In addition to the 17 ballets he’s created nation’s capital. With works by emerging and acclaimed for ABT, Ratmansky has choreographed genre-defining ballets choreographers Silas Farley, dancer and choreographer for the Mariinsky Ballet, the Royal Danish Ballet, the Royal with the New York City Ballet; Dana Genshaft, former San Swedish Ballet, Dutch National Ballet, New York City Ballet, Francisco Ballet soloist and returning TWB choreographer; San Francisco Ballet, The Australian Ballet and more, as well as and Stanton Welch, Artistic Director of the Houston Ballet, for ballet greats Nina Ananiashvili, Diana Vishneva, and Mikhail energy and inspiration will abound from the studio, to the Baryshnikov. -

Iolanta Bluebeard's Castle

iolantaPETER TCHAIKOVSKY AND bluebeard’sBÉLA BARTÓK castle conductor Iolanta Valery Gergiev Lyric opera in one act production Libretto by Modest Tchaikovsky, Mariusz Treliński based on the play King René’s Daughter set designer by Henrik Hertz Boris Kudlička costume designer Bluebeard’s Castle Marek Adamski Opera in one act lighting designer Marc Heinz Libretto by Béla Balázs, after a fairy tale by Charles Perrault choreographer Tomasz Wygoda Saturday, February 14, 2015 video projection designer 12:30–3:45 PM Bartek Macias sound designer New Production Mark Grey dramaturg The productions of Iolanta and Bluebeard’s Castle Piotr Gruszczyński were made possible by a generous gift from Ambassador and Mrs. Nicholas F. Taubman general manager Peter Gelb Additional funding was received from Mrs. Veronica Atkins; Dr. Magdalena Berenyi, in memory of Dr. Kalman Berenyi; music director and the National Endowment for the Arts James Levine principal conductor Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera and Fabio Luisi Teatr Wielki–Polish National Opera The 5th Metropolitan Opera performance of PETER TCHAIKOVSKY’S This performance iolanta is being broadcast live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera International Radio Network, sponsored conductor by Toll Brothers, Valery Gergiev America’s luxury in order of vocal appearance homebuilder®, with generous long-term marta duke robert support from Mzia Nioradze Aleksei Markov The Annenberg iol anta vaudémont Foundation, The Anna Netrebko Piotr Beczala Neubauer Family Foundation, the brigit te Vincent A. Stabile Katherine Whyte Endowment for Broadcast Media, l aur a and contributions Cassandra Zoé Velasco from listeners bertr and worldwide. Matt Boehler There is no alméric Toll Brothers– Keith Jameson Metropolitan Opera Quiz in List Hall today. -

Swan Lake Audience Guide

February 16 - 25, 2018 Benedum Center for the Performing Arts, Pittsburgh Choreography: Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov Staging: Terrence S. Orr Music: Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Swan Lake Sponsors: The Benter Foundation, The Pittsburgh Foundation, Eden Hall Foundation, Anonymous Donor February 16 - 25, 2018 Benedum Center for the Performing Arts | Pittsburgh, PA PBT gratefully acknowledges the following organizations for their commitment to our education programming: Allegheny Regional Asset District Henry C. Frick Educational Fund of The Buhl Anne L. and George H. Clapp Charitable Foundation Trust BNY Mellon Foundation Highmark Foundation Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation Peoples Natural Gas Eat ‘n Park Hospitality Group Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Edith L. Trees Charitable Trust Pennsylvania Department of Community ESB Bank and Economic Development Giant Eagle Foundation PNC Bank Grow up Great The Grable Foundation PPG Industries, Inc. Hefren-Tillotson, Inc. Richard King Mellon Foundation James M. The Heinz Endowments and Lucy K. Schoonmaker Cover Photo: Duane Rieder Artist: Amanda Cochrane 1 3 The Setting and Characters 3 The Synopsis 5 About Swan Lake 6 The Origins of the Swan Lake Story 6 Swan Lake Timeline 7 The Music 8 The Choreography 9 The Dual Role of Odette + Odile 9 Acts 1 & 3 10 Spotlight on the Black Swan Pas de Deux 10 The Grand Pas Explained 11 What’s a fouette? 11 Acts 2 & 4 12 Dance of the Little Swans 13 The White Act 13 Costumes and Scenic Design 13 Costumes By the Numbers 14 The Tutus 14 A Few Costume Tidbits! 15 Did You Know? Before She was the Black Swan 16 Programs at the Theater 17 Accessibility 2 The Setting The ballet takes place in and near the European castle of Prince Siegfried, long ago. -

Ballet Notes Giselle

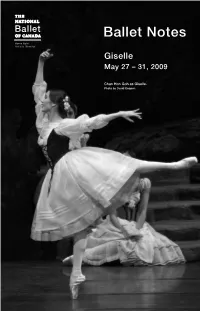

Ballet Notes Giselle May 27 – 31, 2009 Chan Hon Goh as Giselle. Photo by David Cooper. 2008/09 Orchestra Violins Clarinets • Fujiko Imajishi, • Max Christie, Principal Souvenir Book Concertmaster Emily Marlow, Lynn Kuo, Acting Principal Acting Concertmaster Gary Kidd, Bass Clarinet On Sale Now in the Lobby Dominique Laplante, Bassoons Principal Second Violin Stephen Mosher, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., Founder James Aylesworth, Jerry Robinson Featuring beautiful new images Acting Assistant Elizabeth Gowen, George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Concertmaster by Canadian photographer Contra Bassoon Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Jennie Baccante Sian Richards Artistic Director Executive Director Sheldon Grabke Horns Xiao Grabke Gary Pattison, Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Nancy Kershaw Vincent Barbee Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-Leheniuk Derek Conrod Principal Conductor • Csaba Koczó • Scott Wevers Yakov Lerner Trumpets Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Jayne Maddison Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Richard Sandals, Principal Ron Mah YOU dance / Ballet Master Mark Dharmaratnam Aya Miyagawa Raymond Tizzard Aleksandar Antonijevic, Guillaume Côté, Wendy Rogers Chan Hon Goh, Greta Hodgkinson, Filip Tomov Trombones Nehemiah Kish, Zdenek Konvalina, Joanna Zabrowarna David Archer, Principal Heather Ogden, Sonia Rodriguez, Paul Zevenhuizen Robert Ferguson David Pell, Piotr Stanczyk, Xiao Nan Yu Violas Bass Trombone Angela Rudden, Principal Victoria Bertram, Kevin D. Bowles, Theresa Rudolph Koczó, Tuba -

You Conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in Their Annual Ball at the Musikverein, the Day Before Yesterday

Interview with conductor Semyon Bychkov Tutti-magazine: You conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in their annual ball at the Musikverein, the day before yesterday. What did you take away from the experience ? Semyon Bychkov: It was an extraordinary experience, it is hard to find words to describe it. The women and the debutantes were dressed in sumptuous ball gowns and the atmosphere made it feel as if one were in the 19th century. For someone like me who sometimes wishes they’d lived in the 18th or 19th centuries, the evening reminded me of a style approrpriate to a particularly beautiful past. As I’ve said many times to your colleagues, I would be very happy if this beautiful and joyful spirit could be shared by as many people as possible and offer an alternative to the vulgarity and violence which occur daily in the world today. As I was leaving on tour with the Vienna Philharmonic, I arrived to drop my things off at the Great Hall of the Musikverein in the afternoon – the following day we would be playing in Hamburg at the Elbphilharmonie - the Hall was deserted and the view was so extraordinary that I couldn’t resist taking some photographs : all the stalls seats had been removed and replaced by flowers and tables. Of course I also noticed the wall covered with photographs of conductors who had worked with the orchestra, and thought: «So here is the conductors’ wall of fame»… That evening, immediately after our concert, everything that had been installed was moved to the large empty space under the floor of the Hall. -

Sanrio Company, Ltd

May 15, 2015 Summary of Financial Results for the Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2015 (FY2014) [Japanese GAAP] Company name: Sanrio Company, Ltd. Listed Stock Exchange: TSE 1st Section Stock code: 8136 URL: http://www.sanrio.co.jp/english/corporate/ir/ Representative: Shintaro Tsuji, President and Chief Executive Officer Inquiries: Susumu Emori, Managing Director TEL: +81-3-3779-8058 Scheduled date of Annual General Meeting of Shareholders: June 25, 2015 Scheduled date of filing of Annual Securities Report: June 26, 2015 Starting date of dividend payment: June 9, 2015 Preparation of supplementary materials for financial results: Yes Holding of financial results meeting: Yes (for institutional investors and analysts) Note: The original disclosure in Japanese was released on May 15, 2015 at 16:00 (GMT +9). (All amounts are rounded down to the nearest million yen) 1. Consolidated Financial Results for FY2014 (April 1, 2014 – March 31, 2015) (1) Consolidated results of operations (Percentages for sales and profits represent year-on-year changes) Sales Operating Profit Ordinary Profit Net Profit Millions of yen % Millions of yen % Millions of yen % Millions of yen % FY2014 74,562 (3.2) 17,468 (16.9) 18,525 (8.2) 12,804 0.0 FY2013 77,009 3.7 21,019 4.1 20,180 2.7 12,802 2.1 Note: Comprehensive income (millions of yen) FY2014: 16,163 (down 21.2%) FY2013: 20,513 (up 22.9%) Net Profit per Fully-Diluted Net Return on Equity Return on Assets Operating Profit Share Profit per Share (ROE) (ROA) to Sales Yen Yen % % % FY2014 146.53 - 20.1 15.5 23.4 FY2013 145.24 145.20 23.2 18.8 27.3 Reference: Equity in earnings of unconsolidated subsidiaries (millions of yen) FY2014: - FY2013: - (2) Consolidated financial position Total Assets Net Assets Equity Ratio Net Assets per Share Millions of yen Millions of yen % Yen As of Mar. -

Study Guide Table of Contents Pre-Performance Activities and Information

For Grades K - 12 STUDY GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS PRE-PERFORMANCE ACTIVITIES AND INFORMATION TEKS Addressed 3 Attending a ballet performance 5 The story of The Nutcracker 6 The Science Behind The Snow 13 The Artists Who Created Nutcracker: Choreographers 16 The Artists Who Created Nutcracker: Composer 17 The Artists Who Created Nutcracker: Designer 18 Animals Around The World 19 Dancers From Around The World 21 Look Ma, No Words 22 Why Do They Wear That? 24 Ballet Basics: Fantastic Feet 25 Ballet Basics: All About Arms 26 Houston Ballet: 1955 To Today 27 Appendix A: Mood Cards 28 Appendix B: Set Design 29 Appendix C: Costume Design 30 Appendix D: Glossary 31 Program Evaluation 33 2 LEARNING OUTCOMES Students who attend the performance and utilize the study guide will be able to: • Identify different countries from around the world; • Describe the science behind the snow used in The Nutcracker; • Describe at least one dance from The Nutcracker in words or pictures; • Demonstrate appropriate audience behavior. TEKS ADDRESSED §112.11. SCIENCE, KINDERGARTEN (6) Force, motion, and energy. The student knows that energy, force, and motion are related and are a part of their everyday life §117.112. MUSIC, GRADE 3 (1) Foundations: music literacy. The student describes and analyzes musical sound. §117.109. MUSIC, GRADE 2 (1) Foundations: music literacy. The student describes and analyzes musical sound. (6) Critical evaluation and response. The student listens to, responds to, and evaluates music and musical performances. §117.106. MUSIC, ELEMENTARY (5) Historical and cultural relevance. The student examines music in relation to history and cultures. -

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto Friday, January 12, 2018 at 11 am Jayce Ogren, Guest conductor Sibelius Symphony No. 7 in C Major Tchaikovsky Concerto for Violin and Orchestra Gabriel Lefkowitz, violin Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto For Tchaikovsky and The Composers Sibelius, these works were departures from their previ- ous compositions. Both Jean Sibelius were composed in later pe- (1865—1957) riods in these composers’ lives and both were pushing Johan Christian Julius (Jean) Sibelius their comfort levels. was born on December 8, 1865 in Hämeenlinna, Finland. His father (a doctor) died when Jean For Tchaikovsky, the was three. After his father’s death, the family Violin Concerto came on had to live with a variety of relatives and it was Jean’s aunt who taught him to read music and the heels of his “year of play the piano. In his teen years, Jean learned the hell” that included his disas- violin and was a quick study. He formed a trio trous marriage. It was also with his sister older Linda (piano) and his younger brother Christian (cello) and also start- the only concerto he would ed composing, primarily for family. When Jean write for the violin. was ready to attend university, most of his fami- Jean Sibelius ly (Christian stayed behind) moved to Helsinki For Sibelius, his final where Jean enrolled in law symphony became a chal- school but also took classes at the Helsinksi Music In- stitute. Sibelius quickly became known as a skilled vio- lenge to synthesize the tra- linist as well as composer. He then spent the next few ditional symphonic form years in Berlin and Vienna gaining more experience as a composer and upon his return to Helsinki in 1892, he with a tone poem. -

PETER TCHAIKOVSKY Arr. ROBERT LONGFIELD Highlights from 1812

KJOS CONCERT BAND TRADITION OF EXCELLENCE™ GRADE 3 EXCELLENCE IN PERFORMANCE WB466F $7.00 PETER TCHAIKOVSKY arr. ROBERT LONGFIELD Highlights from 1812 Overture Correlated with TRADITION OF EXCELLENCE™ Book 3, Page 30 Correlated with TRADITION OF EXCELLENCE™ Books 1, 2, & 3 when performed as a mass band with all available parts. SAMPLE NEIL A. KJOS MUSIC COMPANY • PUBLISHER 2 SAMPLE WB466 3 About the Composer Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic era whose compositions remain popular to this day. Among his most popular works are three ballets, Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, and Te Nutcracker, six symphonies, eleven operas, the tone poems Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture, Marche Slave, Capriccio Italien, and 1812 Overture, a concerto for violin, and two concertos for piano. Tchaikovsky’s music was the frst by a Russian composer to achieve international recognition. Later in his career, Tchaikovsky made appearances around the globe as a guest conductor, including the 1891 inaugural concert of Carnegie Hall in New York City. In the late 1880s, he was awarded a lifetime pension by Emperor Alexander III of Russia. But, Tchaikovsky batled many personal crises and depression throughout his career, despite his popular successes. Nine days afer he conducted the premiere of his Sixth Symphony, “the Pathétique,” Tchaikovsky died. Te circumstances of his death are shrouded in ambiguity. Te ofcial report states that he contracted cholera from drinking contaminated river water. However, at this time in St. Petersburg, a death from cholera was practically unheard of for someone Tchaikovsky’s wealth. For this reason, many people, including members of his family, believe that his death is the result of suicide related to the depression he batled during his life. -

Super-Heroes of the Orchestra

S u p e r - Heroes of the Orchestra TEACHER GUIDE THIS BELONGS TO: _________________________ 1 Dear Teachers: The Arkansas Symphony Orchestra is presenting SUPER-HEROES OF THE SYMPHONY this year to area students. These materials will help you integrate the concert experience into the classroom curriculum. Music communicates meaning just like literature, poetry, drama and works of art. Understanding increases when two or more of these media are combined, such as illustrations in books or poetry set to music ~~ because multiple senses are engaged. ABOUT ARTS INTEGRATION: As we prepare students for college and the workforce, it is critical that students are challenged to interpret a variety of ‘text’ that includes art, music and the written word. By doing so, they acquire a deeper understanding of important information ~~ moving it from short-term to long- term memory. Music and art are important entry points into mathematical and scientific understanding. Much of the math and science we teach in school are innate to art and music. That is why early scientists and mathematicians, such as Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Pythagoras, were also artists and musicians. This Guide has included literacy, math, science and social studies lesson planning guides in these materials that are tied to grade-level specific Arkansas State Curriculum Framework Standards. These lesson planning guides are designed for the regular classroom teacher and will increase student achievement of learning standards across all disciplines. The students become engaged in real-world applications of key knowledge and skills. (These materials are not just for the Music Teacher!) ABOUT THE CONTENT: The title of this concert, SUPER-HEROES OF THE SYMPHONY, suggests a focus on musicians/instruments/real and fictional people who do great deeds to help achieve a common goal.