Japanese Tea Ritual, Dynamic Mythology, and National Identity Jennifer L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOT TYPESET LOW HIGH 7000 German Porcelain Figural Group

LOT TYPESET LOW HIGH 7000 German porcelain figural group, depicting a pianist and dancers, each dressed in classical $ 500 $ 700 attire with crinoline accents, marked with underglaze blue mark, 11.5"h x 16"w x 9"d 7001 Framed group of 32 Wedgwood jasperware medallions, each depicting British royalty, $ 300 $ 500 overall 17.5"h x 33"w 7002 (lot of 2) Continental polychrome decorated pill boxes, including a Meissen example, $ 300 $ 500 largest 1"h x 2.5"w 7003 (lot of 2) Meissen figural candlestick group 19th century, each depicted holding a child, one $ 1,200 $ 1,500 figure in the Bacchanalian taste, having a grape cluster wreath, each depicted in Classical attire, and rising on a Rococco style base with bird form reserves, underside with underglaze blue cross sword mark, 13,5"h 7004 Continental style gilt bronze footed compote, having a garland swag decorated frieze $ 600 $ 900 flanking the ebonized bowl, above the fish form gilt bronze standard, and rising on a circular marble base, 8.5"h x 8"w 7005 (lot of 8) French hand painted porcelain miniature portraits; each depicting French royalty $ 800 $ 1,200 including Napoleon, and numerous ladies, largest 4"h x 3"w Provenance: from the Holman Estate in Pacific Grove. The Holman family were early residents of the Monterey Peninsula and established Holman's Department Store in the center of Pacific Grove, thence by family descent 7006 French Grand Tour style silver gilt mythological figure, depicting Bacchus or Dionysus, $ 1,500 $ 2,000 modeled as standing on a mound of grapes and leaves holding -

Notes Toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo

The Shrine : Notes toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo By A.W. S a d l e r Sarah Lawrence College When I arrived in Japan in the autumn of 1965, I settled my family into our home-away-from-home in a remote comer of Bunkyo-ku3 in Tokyo, and went to call upon an old timer,a man who had spent most of his adult life in Tokyo. I told him of my intention to carry out an exhaustive study of the annual festivals (taisai) of a typical neighbor hood shrine (jinja) in my area of residence,and I told him I had a full year at my disposal for the task. “Start on the grounds of the shrine/,was his solid advice; “go over every tsubo '(every square foot3 we might say),take note of every stone, investigate every marker.” And that is how I began. I worked with the shrines closest to home so that shrine and people would be part of my everyday life. When my wife and I went for an evening stroll, we invariably happened upon the grounds of one of our shrines; when we went to the market for fish or pencils or raaisnes we found ourselves visiting with the ujiko (parishioners; literally,children of the god of the shrine, who is guardian spirit of the neighborhood) of the shrine. I started with five shrines. I had great difficulty arranging for interviews with the priests of two of the five (the reasons for their reluc tance to visit with me will be discussed below) ; one was a little too large and famous for my purposes,and another was a little too far from home for really careful scrutiny. -

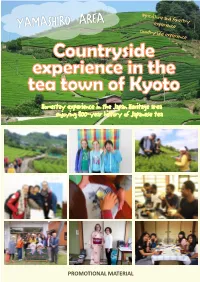

Enjoying 800-Year History of Japanese Tea

Homestay experience in the Japan Heritage area enjoying 800-year history of Japanese tea PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL ●About Yamashiro area The area of the Japanese Heritage "A walk through the 800-year history of Japanese tea" Yamashiro area is in the southern part of Kyoto Prefecture and famous for Uji Tea, the exquisite green tea grown in the beautiful mountains. Beautiful tea fields are covering the mountains, and its unique landscape with houses and tea factories have been registered as the Japanese Heritage “A Walk through the 800-year History of Japanese Tea". Wazuka Town and Minamiyamashiro Village in Yamashiro area produce 70% of Kyoto Tea, and the neighborhood Kasagi Town offers historic sightseeing places. We are offering a countryside homestay experience in these towns. わづかちょう 和束町 WAZUKA TOWN Tea fields in Wazuka Tea is an evergreen tree from the camellia family. You can enjoy various sceneries of the tea fields throughout the year. -1- かさぎちょう 笠置町 KASAGI TOWN みなみやましろむら 南山城村 MINAMI YAMASHIRO VILLAGE New tea leaves / Spring Early rice harvest / Autumn Summer Pheasant Tea flower / Autumn Memorial service for tea Persimmon and tea fields / Autumn Frosty tea field / Winter -2- ●About Yamashiro area Countryside close to Kyoto and Nara NARA PARK UJI CITY KYOTO STATION OSAKA (40min) (40min) (a little over 1 hour) (a little over 1 hour) The Yamashiro area is located one hour by car from Kyoto City and Osaka City, and it is located 30 to 40 minutes from Uji City and Nara City. Since it is surrounded by steep mountains, it still remains as country side and we have a simple country life and abundant nature even though it is close to the urban area. -

Japanese Tea Ceremony: How It Became a Unique Symbol of the Japanese Culture and Shaped the Japanese Aesthetic Views

International J. Soc. Sci. & Education 2021 Vol.11 Issue 1, ISSN: 2223-4934 E and 2227-393X Print Japanese Tea Ceremony: How it became a unique symbol of the Japanese culture and shaped the Japanese aesthetic views Yixiao Zhang Hangzhou No.2 High School of Zhejiang Province, CHINA. [email protected] ABSTRACT In the process of globalization and cultural exchange, Japan has realized a host of astonishing achievements. With its unique cultural identity and aesthetic views, Japan has formed a glamorous yet mysterious image on the world stage. To have a comprehensive understanding of Japanese culture, the study of Japanese tea ceremony could be of great significance. Based on the historical background of Azuchi-Momoyama period, the paper analyzes the approaches Sen no Rikyu used to have the impact. As a result, the impact was not only on the Japanese tea ceremony itself, but also on Japanese culture and society during that period and after.Research shows that Tea-drinking was brought to Japan early in the Nara era, but it was not integrated into Japanese culture until its revival and promotion in the late medieval periods under the impetus of the new social and religious realities of that age. During the Azuchi-momoyama era, the most significant reform took place; 'Wabicha' was perfected by Takeno Jouo and his disciple Sen no Rikyu. From environmental settings to tea sets used in the ritual to the spirit conveyed, Rikyu reregulated almost all aspects of the tea ceremony. He removed the entertaining content of the tea ceremony, and changed a rooted aesthetic view of Japanese people. -

Japanese Garden

満開 IN BLOOM A PUBLICATION FROM WATERFRONT BOTANICAL GARDENS SPRING 2021 A LETTER FROM OUR 理事長からの PRESIDENT メッセージ An opportunity was afforded to WBG and this region Japanese Gardens were often built with tall walls or when the stars aligned exactly two years ago! We found hedges so that when you entered the garden you were out we were receiving a donation of 24 bonsai trees, the whisked away into a place of peace and tranquility, away Graeser family stepped up with a $500,000 match grant from the worries of the world. A peaceful, meditative to get the Japanese Garden going, and internationally garden space can teach us much about ourselves and renowned traditional Japanese landscape designer, our world. Shiro Nakane, visited Louisville and agreed to design a two-acre, authentic Japanese Garden for us. With the building of this authentic Japanese Garden we will learn many 花鳥風月 From the beginning, this project has been about people, new things, both during the process “Kachou Fuugetsu” serendipity, our community, and unexpected alignments. and after it is completed. We will –Japanese Proverb Mr. Nakane first visited in September 2019, three weeks enjoy peaceful, quiet times in the before the opening of the Waterfront Botanical Gardens. garden, social times, moments of Literally translates to Flower, Bird, Wind, Moon. He could sense the excitement for what was happening learning and inspiration, and moments Meaning experience on this 23-acre site in Louisville, KY. He made his of deep emotion as we witness the the beauties of nature, commitment on the spot. impact of this beautiful place on our and in doing so, learn children and grandchildren who visit about yourself. -

Newsletter 13 (June 2014)

June 2014 - Volume 6 - Issue 2 June 2014 - Volume 6 - Issue 2 国際基督教大学ロータリー平和センター ニューズレター ICU Rotary Peace Center Newsletter Rotary Peace Center Staff Director: Masaki Ina Associate Director: Giorgio Shani G.S. Office Manager: Masako Mitsunaga Coordinator: Satoko Ohno Contact Information: Rotary Peace Center International Christian University 3-10-2 Osawa, Mitaka, Tokyo 181-8585 Tel: +81 422 33 3681 Fax: +81 422 33 3688 [email protected] http://subsite.icu.ac.jp/rotary/ Index In this issue: 2 - Trailblazing Events 4 - Preparing For Peace 5 - Experiential Learning Reflections 7 - Meet The Families of Class XII Fellows 10 - Class XI Thesis Summaries 15 - Class XII AFE Placements 16 - Gratitude and Appreciation from Class XII 1 Trailblazing Events ICU Celebrates First Ever Black History Month by Nixon Nembaware Being an International University, ICU brings together students and Faculty members of various backgrounds and races. It is thus a suitable place to cultivate understanding of different cultures and heritages. This was the thinking that Rotary Peace Fellow Class XII had in mind when they partnered with the Social Science Research Institute to celebrate the first ever Black History Month commemoration at ICU. Two main events were lined up, first was a dialogue with Dr. Mohau Pheko, Ambassador of the Republic of South Africa to Japan who visited our campus to give an open lecture on the legacy of ‘Nelson Mandela’ and the history of black people in South Africa. Second was a dialogue with Ms. Judith Exavier, Ambassador of the Republic of Haiti to Japan. She talked of the history of the black people in the Caribbean Island and linked the history of slavery to what prospects lie ahead for black people the world over. -

The Abode of Fancy, of Vacancy, and of the Unsymmetrical

The University of Iceland School of Humanities Japanese Language and Culture The Abode of Fancy, of Vacancy, and of the Unsymmetrical How Shinto, Daoism, Confucianism, and Zen Buddhism Interplay in the Ritual Space of Japanese Tea Ceremony BA Essay in Japanese Language and Culture Francesca Di Berardino Id no.: 220584-3059 Supervisor: Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir September 2018 Abstract Japanese tea ceremony extends beyond the mere act of tea drinking: it is also known as chadō, or “the Way of Tea”, as it is one of the artistic disciplines conceived as paths of religious awakening through lifelong effort. One of the elements that shaped its multifaceted identity through history is the evolution of the physical space where the ritual takes place. This essay approaches Japanese tea ceremony from a point of view that is architectural and anthropological rather than merely aesthetic, in order to trace the influence of Shinto, Confucianism, Daoism, and Zen Buddhism on both the architectural elements of the tea room and the different aspects of the ritual. The structure of the essay follows the structure of the space where the ritual itself is performed: the first chapter describes the tea garden where guests stop before entering the ritual space of the tea room; it also provides an overview of the history of tea in Japan. The second chapter figuratively enters the ritual space of the tea room, discussing how Shinto, Confucianism, Daoism, and Zen Buddhism merged into the architecture of the ritual space. Finally, the third chapter looks at the preparation room, presenting the interplay of the four cognitive systems within the ritual of making and serving tea. -

Vast Waters by Frederick R

Vast Waters By Frederick R. Dannaway n the year 1833, on the 15th day of the eight month, a group of Japanese tea mystics placed a jar of Chinese I depending on its source. Many tea-masters confirm the water deep into the source of the Yodo River that flows potency of specific mountain springs and show a prefer- into Kyoto, Japan. In contrast to the wasting of tea as ence for old or wild tree teas (also from famous moun- protest in Boston, these sencha adepts felt guilty in hord- tains) for both flavor and for their energy and healing ing the precious—and laboriously imported—Chinese powers. These attributes, if deduced empirically through water and so decided to release it into their home waters generations of observations as well as from a Daoist and thus share its potency with their countrymen. The “mystical primitivism”, can be seen to have retained an ring-leader of this plot, the literati tea-master Kakuo, influence from the earliest religious observances of water had requisitioned the water from China via Nagasaki in China and into Japan. On a practical level, water and and after a year’s wait was blessed with three bottles(18 tea from remote areas would indeed have special charac- liters) of the water. There was a brief reactionary re- teristics, such as taste or purity, as well as a metaphysical sponse to the plan by the government who “feared the association with the powerful mountains and wilderness Chinese water would poison the drinking supply” but that were the mystical abodes of the Immortals. -

Umami Café by AJINOMOTO CO

Umami Café BY AJINOMOTO CO. The Tea Experience For centuries, green tea has been treasured throughout Asia for its healthful, restorative qualities. In Japan, Zen priests drank green tea to keep them awake through long hours of meditation. In the 16th century, a man named Sen no Rikyù, influenced by the study of Zen, envisioned a path to enlightenment through the simple act of sharing a bowl of tea among friends in the spirit of peace and harmony—a practice he called wabi-cha. For Rikyu, making tea while mindfully engaging all the senses was to have a complete Zen experience. We are pleased to have you share a moment of quiet joy with us and experience the spirit of Japanese culture through a simple bowl of tea. Tea Sets We’ve paired traditional teas with Japanese sweets. A great place to start. Matcha with Hanabira Mochi GF V $14 Sencha with Fried Rice A bowl of hand-whisked, jade green matcha is paired with a traditional Japanese tea ceremony sweet. Tender sheets of mochi rice dough The light, sweetness of our Sencha balances nicely with the strong umami flavors of either our Yakitori Chicken Style Fried Rice ($14) or our are folded over candied burdock root and filled with sweetened white bean paste infused with a hint of miso. Takikomi Gohan Style Vegetable Fried Rice V ($12). Additional tea steepings available upon request. Sencha with Castella Cake $12 Matcha with Mochi Ice Cream GF $12 Genmaicha with Manju $11 Hojicha with Shortbread Cookies $9 The light, mild sweetness of the Sencha is enhanced by this A bowl of our hand-whisked matcha is paired with a premium Genmaicha, with its roasted rice and earthy flavor, is a perfect These bitter chocolate and vanilla cookies highlight the aromatic popular Japanese sponge cake. -

Design Examples Informational Handouts Check Online for Available Templates –

BRAND BOOK Design Examples Informational Handouts Check online for available templates – www.csus.edu/brand 2.18 HEADLINE OR EVENT HEADLINE OR NAME OF NAME GOES HERE YOUR EVENT GOES HERE This is where your event subhead goes. This is where your event subhead goes. SIDE MARGIN SUBHEAD SUBHEAD Side margin is body text. Use this text Second Subhead style for your side margin. Side margin Body text goes here. Body text goes here. Body text goes here. Body text SIDE MARGIN SUBHEAD SUBHEAD is body text. Use this text style for your goes here. Body text goes here. Body text goes here. Body text goes here. Side margin is body text. Use the Second Subhead side margin. Side margin is body text. body text style for your side margin. Body text goes here. Body text goes here. Body text goes here. Body text This is the body text style. Use this style for body text. This is the body text style. Use this text style for your side margin. goes here. Body text goes here. Body text goes here. Side margin is body text. Use this text Use this style for body text. This is the body text style. Use this style for body text. Side margin is body text. Use this text style for your side margin. Side This is the body text style. This is the body text style. Use this style for body text. Here is a bullet style. Use this style for your bullet points. Here is the style for your side margin. • margin is body text. -

A Performer's Guide to Minoru Miki's Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988)

University of Cincinnati Date: 4/22/2011 I, Margaret T Ozaki-Graves , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Voice. It is entitled: A Performer’s Guide to Minoru Miki’s _Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano_ (1988) Student's name: Margaret T Ozaki-Graves This work and its defense approved by: Committee chair: Jeongwon Joe, PhD Committee member: William McGraw, MM Committee member: Barbara Paver, MM 1581 Last Printed:4/29/2011 Document Of Defense Form A Performer’s Guide to Minoru Miki’s Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988) A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music by Margaret Ozaki-Graves B.M., Lawrence University, 2003 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2007 April 22, 2011 Committee Chair: Jeongwon Joe, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Japanese composer Minoru Miki (b. 1930) uses his music as a vehicle to promote cross- cultural awareness and world peace, while displaying a self-proclaimed preoccupation with ethnic mixture, which he calls konketsu. This document intends to be a performance guide to Miki’s Sohmon III: for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988). The first chapter provides an introduction to the composer and his work. It also introduces methods of intercultural and artistic borrowing in the Japanese arts, and it defines the four basic principles of Japanese aesthetics. The second chapter focuses on the interpretation and pronunciation of Sohmon III’s song text. -

Matcha Chasen

Simple Solutions@ Study Skills Level5 Sample Lesson #1 Working with Longer Passages: Look for the Big Picture There is usually one big picture or main idea in a reading selection. The title - if there is one - may give a clue about the main idea. Sometimes you can figureo ut the big picture by reading just the first sentence of every paragraph. Each paragraph has its own main idea related to the big picture. You can find the main idea of each paragraph by locating the topic sentence. Read the following selection and complete items 1 - 8. The Japanese Tea Ceremony The Japanese Tea Ceremony, called a chado, is a very elaborate and beautiful ritual. Cha means "tea", and do means "the way of," so chado is "the way of tea." Each part of the chado is practiced in a precise way according to ancient traditions. Even the most modern of tea ceremonies includes the basics: a simple room decorated with fresh flowers or wall hangings, an attitude of peace, and a deep respect for the host, the guests, the tea, and even the utensils used to make the tea. The purpose of the tea ceremony is to stop and enjoy a relaxing moment in the midst of a hectic day. Participants take the time to savor the tea and to honor each other. Guests at a Japanese tea ceremony show respect by moving slowly, bowing deeply, and speaking quietly. In fact, there is very little talking at all in the tea room where the ritual takes place. The place where people gather for the tea ceremony is called a chashitsu.