Thesis Folio.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

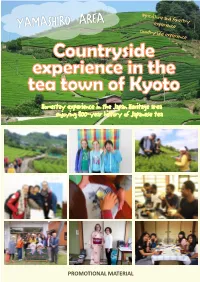

Enjoying 800-Year History of Japanese Tea

Homestay experience in the Japan Heritage area enjoying 800-year history of Japanese tea PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL ●About Yamashiro area The area of the Japanese Heritage "A walk through the 800-year history of Japanese tea" Yamashiro area is in the southern part of Kyoto Prefecture and famous for Uji Tea, the exquisite green tea grown in the beautiful mountains. Beautiful tea fields are covering the mountains, and its unique landscape with houses and tea factories have been registered as the Japanese Heritage “A Walk through the 800-year History of Japanese Tea". Wazuka Town and Minamiyamashiro Village in Yamashiro area produce 70% of Kyoto Tea, and the neighborhood Kasagi Town offers historic sightseeing places. We are offering a countryside homestay experience in these towns. わづかちょう 和束町 WAZUKA TOWN Tea fields in Wazuka Tea is an evergreen tree from the camellia family. You can enjoy various sceneries of the tea fields throughout the year. -1- かさぎちょう 笠置町 KASAGI TOWN みなみやましろむら 南山城村 MINAMI YAMASHIRO VILLAGE New tea leaves / Spring Early rice harvest / Autumn Summer Pheasant Tea flower / Autumn Memorial service for tea Persimmon and tea fields / Autumn Frosty tea field / Winter -2- ●About Yamashiro area Countryside close to Kyoto and Nara NARA PARK UJI CITY KYOTO STATION OSAKA (40min) (40min) (a little over 1 hour) (a little over 1 hour) The Yamashiro area is located one hour by car from Kyoto City and Osaka City, and it is located 30 to 40 minutes from Uji City and Nara City. Since it is surrounded by steep mountains, it still remains as country side and we have a simple country life and abundant nature even though it is close to the urban area. -

Japanese Tea Ceremony: How It Became a Unique Symbol of the Japanese Culture and Shaped the Japanese Aesthetic Views

International J. Soc. Sci. & Education 2021 Vol.11 Issue 1, ISSN: 2223-4934 E and 2227-393X Print Japanese Tea Ceremony: How it became a unique symbol of the Japanese culture and shaped the Japanese aesthetic views Yixiao Zhang Hangzhou No.2 High School of Zhejiang Province, CHINA. [email protected] ABSTRACT In the process of globalization and cultural exchange, Japan has realized a host of astonishing achievements. With its unique cultural identity and aesthetic views, Japan has formed a glamorous yet mysterious image on the world stage. To have a comprehensive understanding of Japanese culture, the study of Japanese tea ceremony could be of great significance. Based on the historical background of Azuchi-Momoyama period, the paper analyzes the approaches Sen no Rikyu used to have the impact. As a result, the impact was not only on the Japanese tea ceremony itself, but also on Japanese culture and society during that period and after.Research shows that Tea-drinking was brought to Japan early in the Nara era, but it was not integrated into Japanese culture until its revival and promotion in the late medieval periods under the impetus of the new social and religious realities of that age. During the Azuchi-momoyama era, the most significant reform took place; 'Wabicha' was perfected by Takeno Jouo and his disciple Sen no Rikyu. From environmental settings to tea sets used in the ritual to the spirit conveyed, Rikyu reregulated almost all aspects of the tea ceremony. He removed the entertaining content of the tea ceremony, and changed a rooted aesthetic view of Japanese people. -

The Abode of Fancy, of Vacancy, and of the Unsymmetrical

The University of Iceland School of Humanities Japanese Language and Culture The Abode of Fancy, of Vacancy, and of the Unsymmetrical How Shinto, Daoism, Confucianism, and Zen Buddhism Interplay in the Ritual Space of Japanese Tea Ceremony BA Essay in Japanese Language and Culture Francesca Di Berardino Id no.: 220584-3059 Supervisor: Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir September 2018 Abstract Japanese tea ceremony extends beyond the mere act of tea drinking: it is also known as chadō, or “the Way of Tea”, as it is one of the artistic disciplines conceived as paths of religious awakening through lifelong effort. One of the elements that shaped its multifaceted identity through history is the evolution of the physical space where the ritual takes place. This essay approaches Japanese tea ceremony from a point of view that is architectural and anthropological rather than merely aesthetic, in order to trace the influence of Shinto, Confucianism, Daoism, and Zen Buddhism on both the architectural elements of the tea room and the different aspects of the ritual. The structure of the essay follows the structure of the space where the ritual itself is performed: the first chapter describes the tea garden where guests stop before entering the ritual space of the tea room; it also provides an overview of the history of tea in Japan. The second chapter figuratively enters the ritual space of the tea room, discussing how Shinto, Confucianism, Daoism, and Zen Buddhism merged into the architecture of the ritual space. Finally, the third chapter looks at the preparation room, presenting the interplay of the four cognitive systems within the ritual of making and serving tea. -

Vast Waters by Frederick R

Vast Waters By Frederick R. Dannaway n the year 1833, on the 15th day of the eight month, a group of Japanese tea mystics placed a jar of Chinese I depending on its source. Many tea-masters confirm the water deep into the source of the Yodo River that flows potency of specific mountain springs and show a prefer- into Kyoto, Japan. In contrast to the wasting of tea as ence for old or wild tree teas (also from famous moun- protest in Boston, these sencha adepts felt guilty in hord- tains) for both flavor and for their energy and healing ing the precious—and laboriously imported—Chinese powers. These attributes, if deduced empirically through water and so decided to release it into their home waters generations of observations as well as from a Daoist and thus share its potency with their countrymen. The “mystical primitivism”, can be seen to have retained an ring-leader of this plot, the literati tea-master Kakuo, influence from the earliest religious observances of water had requisitioned the water from China via Nagasaki in China and into Japan. On a practical level, water and and after a year’s wait was blessed with three bottles(18 tea from remote areas would indeed have special charac- liters) of the water. There was a brief reactionary re- teristics, such as taste or purity, as well as a metaphysical sponse to the plan by the government who “feared the association with the powerful mountains and wilderness Chinese water would poison the drinking supply” but that were the mystical abodes of the Immortals. -

Umami Café by AJINOMOTO CO

Umami Café BY AJINOMOTO CO. The Tea Experience For centuries, green tea has been treasured throughout Asia for its healthful, restorative qualities. In Japan, Zen priests drank green tea to keep them awake through long hours of meditation. In the 16th century, a man named Sen no Rikyù, influenced by the study of Zen, envisioned a path to enlightenment through the simple act of sharing a bowl of tea among friends in the spirit of peace and harmony—a practice he called wabi-cha. For Rikyu, making tea while mindfully engaging all the senses was to have a complete Zen experience. We are pleased to have you share a moment of quiet joy with us and experience the spirit of Japanese culture through a simple bowl of tea. Tea Sets We’ve paired traditional teas with Japanese sweets. A great place to start. Matcha with Hanabira Mochi GF V $14 Sencha with Fried Rice A bowl of hand-whisked, jade green matcha is paired with a traditional Japanese tea ceremony sweet. Tender sheets of mochi rice dough The light, sweetness of our Sencha balances nicely with the strong umami flavors of either our Yakitori Chicken Style Fried Rice ($14) or our are folded over candied burdock root and filled with sweetened white bean paste infused with a hint of miso. Takikomi Gohan Style Vegetable Fried Rice V ($12). Additional tea steepings available upon request. Sencha with Castella Cake $12 Matcha with Mochi Ice Cream GF $12 Genmaicha with Manju $11 Hojicha with Shortbread Cookies $9 The light, mild sweetness of the Sencha is enhanced by this A bowl of our hand-whisked matcha is paired with a premium Genmaicha, with its roasted rice and earthy flavor, is a perfect These bitter chocolate and vanilla cookies highlight the aromatic popular Japanese sponge cake. -

Weight Managent…

Weight Management… INDEX Chapter 1 Aetiology…11 Chapter 2 How Obesity Measured...16 Chapter 3 Body Fat Distribution...20 Chapter 4 What Causes Obesity...21 Chapter 5 What are the consequences of obesity…27 Chapter 6 Weight Management…51 Chapter 7 Our Weight loss treatment by alternative ways…62 Chapter 8 What is R.M.R or B.M.R...66 1 Weight Management… Chapter 9 Green Tea…73 Chapter 10 Brewing & Serving Green Tea...77 Chapter 11 Green tea & Weight loss...79 Chapter 12 Green Tea; Fat Fighter...81 Chapter 13 Weight Maintenance after Reduction...84 Chapter 14 Success Stories 101 Chapter 15 Variety of green tea...104 Chapter 16 Scientific Study about green tea..120 Chapter 17 Obesity In Children...131 2 Weight Management… Chapter 18 Treatment For Child Obesity...134 Chapter 19 Obesity & Type 2 Diabetes...139 Chapter 20 Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome...142 Chapter 21 Obesity Polycystic ovary Syndrome...143 Chapter 22 Obesity & Reproduction/Sexuality...144 Chapter 23 Obesity & Thyroid Condition...146 Chapter 24 Hormonal Imbalance ...148 Chapter 25 Salt & Obesity...156 Company Profile & Dr.Pratayksha Introduction...161 3 Weight Management… About us We are an emerging health care & slimming center established in 2006. We have achieved tremendous success in the field of curing disorders like obesity, Blood Pressure, All type of Skin disorders and Diabetes with Homeopathic medical science. The foundation of the centr was laid by Dr.PrataykshaBhardwaj, His work has been recognised by many Indian and international organizations in the field of skin care & slimming. Shree Skin Care was earlier founded by Smt. S. -

IKKYU Brochure 2017

PREMIUM JAPANESE GREEN TEA 煎 茶 道 EXCLUSIVELY FROM KYUSHU YOUR BEST CHOICE FOR GREEN TEA IN JAPAN IKKYU G.K. / Noke 8-29-7 / Sawara-ku / Fukuoka city / Japan 814-0171 IKKYU - PREMIUM JAPANESE GREEN TEA / 2 Kyushu Land of Exceptional Green Teas Our green tea comes exclusively from Kyushu, the south- western island of Japan, more than 1’000 km south of Tokyo. It is a lush and vibrant place, with a warm and humid climate. IKKYU green tea is grown in six Kyushu prefectures: Fukuoka (Yame), Nagasaki (Higashi Sonogi), Saga (Ureshino) Kumamoto, Miyazaki and Kagoshima (Chiran). Tea fi elds are nested in alti tude between mountains, on lower plains or by the sea. A wide range of soils and climate conditi ons gives birth to extraordinary and diverse green teas, using lesser known culti vars that yield a sweeter tea. HONSHU KYOTO OSAKA KYUSHU FUKUOKA SHIKOKU IKKYU - PREMIUM JAPANESE GREEN TEA / 3 IKKYU Tea Partners IKKYU has built a strong network of small and medium- sized tea farmers who produce only premium green teas. We collaborate closely to make them reach the overseas markets. Our teas are traceable and we are delighted to share the stories of the people behind them. Their know-how and skills include traditi onal processing methods that make fragrant and delicious green teas, sti ll unknown outside Japan. The excellence of their hard work is celebrated on a regular basis by presti gious awards and grand prizes, at regional, nati onal and internati onal levels. IKKYU is proud to help them share their wonderful creati ons with tea lovers all around the world. -

Matcha Chasen

Simple Solutions@ Study Skills Level5 Sample Lesson #1 Working with Longer Passages: Look for the Big Picture There is usually one big picture or main idea in a reading selection. The title - if there is one - may give a clue about the main idea. Sometimes you can figureo ut the big picture by reading just the first sentence of every paragraph. Each paragraph has its own main idea related to the big picture. You can find the main idea of each paragraph by locating the topic sentence. Read the following selection and complete items 1 - 8. The Japanese Tea Ceremony The Japanese Tea Ceremony, called a chado, is a very elaborate and beautiful ritual. Cha means "tea", and do means "the way of," so chado is "the way of tea." Each part of the chado is practiced in a precise way according to ancient traditions. Even the most modern of tea ceremonies includes the basics: a simple room decorated with fresh flowers or wall hangings, an attitude of peace, and a deep respect for the host, the guests, the tea, and even the utensils used to make the tea. The purpose of the tea ceremony is to stop and enjoy a relaxing moment in the midst of a hectic day. Participants take the time to savor the tea and to honor each other. Guests at a Japanese tea ceremony show respect by moving slowly, bowing deeply, and speaking quietly. In fact, there is very little talking at all in the tea room where the ritual takes place. The place where people gather for the tea ceremony is called a chashitsu. -

Green Teas White Teas Yellow Tea Oolong Teas Pu-Er Teas

GREEN TEAS $ PER OUNCE WHITE TEAS PU-ER TEAS CHINESE CHINESE CHINESE LONG JING TIGER SPRING – Dragonwell $7 BAI MU DAN – White Peony $5 LOOSE PU-ER CHA (Shou) $4 HUANG SHAN MAO FENG $6 YIN ZHEN – Silver Needles $7 CHA TOU – Pu-er Nuggets (Shou) $4.50 DIAN LU ESHAN MAO FENG –Tea King $6 YA BAO – Wild Tea Buds $6 TWO OUNCES OF ANY PRESSED PU-ER $12 BI LUO CHUN TAI HU $6 ! MENGHAI TUO CHA (Shou) $14 per nest TIAN MU LONG ZHU – Dragon Eyes $6 CHI TSE BING CHA (Shou) $35 per cake PUTUO FO CHA – Buddha’s Tea $12 for 2 oz box YELLOW TEA ZHUAN CHA (Shou) $25 per brick LIU’AN GUAPIAN –Watermelon Seeds $6 CHINESE MANDARIN PU-ER (Shou) $6 each SIMAO LONG ZHU – Dragon Pearls $5 MENG DING HUANG YA $6 BAMBOO PU-ER (Shou) $18 each MAO JIAN – 5 Mountains, 2 Pools $4.50 ! PU-ERLA TUO CHA (Shou & Sheng) $.75 each ZHU CHA – Gunpowder $3 BAI BING CHA –White (Sheng) $25 per cake GUI HUA CHA – Osmanthus $4 OOLONG TEAS QING BING RUSTICA – Green(Sheng)$25 per cake MOLI HUA CHA – Jasmine $4 CHINESE LAO SHU BING CHA* –Wild Tree (Sheng) JASMINE PEARLS $5.50 TI KUAN YIN – Iron Goddess of Compassion $5 (*not included in Two Ounce pricing) $30 per cake ARTISAN FLOWERING TEAS $4 each FENG HUANG DAN CONG – Phoenix $5 ! ! DA HONG PAO – Big Red Robe $6 BLACK TEAS JAPANESE SHUI XIAN – Water Nymph $10 for 4 oz tin BANCHA $12 for 2.5 oz packet SHUI XIAN – Water Nymph $4 INDIAN SENCHA $15 for 2.5 oz packet WULONG – Black Dragon $10 for 4 oz box DARJEELING FIRST FLUSH $6 YAMACHA – $16 for 2.5 oz packet ! DARJEELING SECOND FLUSH $6 High Mountain Sencha TAIWANESE DARJEELING HIMALAYA -

Green and White Teas

GREEN AND WHITE TEAS Gunpowder Temple Lü Mao Hou of Heaven „Green –haired Monkey“ is a Gunpowder“. A good sort famous Chinese green tea of this kind of tea. Tiny, from Fu-ťijen province. dark green, shiny leaf, The leaf is spiral-rolled, rolled into a pearl shape. A richly haired and has a balanced infusion with a clear green color. The slight flowery-sweet, infusion is light green with pleasantly bitter-fresh a nutty, flowery aroma taste. and a soft sweet taste. Teapot (1 infusion) 68 CZK Zhong 68 CZK Teapot (3 infusions) 98 CZK Luan Gua Pian Bai Mao Hou „Melon seeds“ hails from „White-haired Monkey“ is a the An-chuej province, famous Chinese green tea and has been popular from Fu-ťijen province. since the age of the Ming The curlier leaves of this dynasty, became known as grey-green tea are richly „Emperor’s tea“ during haired, while its taste is the Qing dynasty. Its full of gentle flowery infusion is a dark green tones, with a sweetly color with an emerald aromatic infusion. shine and a clean, sweet taste. Zhong 68 CZK Teapot (3 infusions) 98 CZK Zhong 68 CZK Teapot (3 infusions) 98 CZK 2 Lu Xue Ya Tian Mu Long Zhu Cha „Green Snow“. Tiny, carefully longrolled leaves „Dragon Eyes“. A hyper- have an emerald color and fine high–quality green tea the bright aroma of green from select fresh tea shoots tea. The tea is prepared harvested on the border of using steam (similar to the Zhe-jiang and Anhui Japanese Sencha teas), provinces. -

Zen and the Art of Tea Alyssa Penrod

Art Zen and the Art of Tea Alyssa Penrod This paper was written for Dr. Joiner’s Non-Western Art History course. The essence of the tea ceremony Is simply to boil water, To make tea, And to drink it—nothing more! Be sure you know this.1 The Japanese tea ceremony, cha no yu, is an integral part of Japanese history. Dating to the 16th century, it has remained an important part of the culture. Tea came to Japan through a Zen monk, Eisai Zenji, who studied in China and brought tea seeds back to his native country in 1191.2 The tea ceremony itself took on multiple forms and was adopted by many groups in Japan. In order to understand fully the tea ceremony, it is essential to know about its history and the Buddhist traditions behind it. The history of Buddhism in Japan can be seen through the development of different strands of the religion. Zen Buddhism developed in Japan and corresponds to the Chinese strand, Chan Buddhism. Buddhism is a very pragmatic religion. It does not focus on the origin of human life, nor does it deify any being, as do many religions. It focuses on the individual’s journey to enlightenment, and it observes everyday life with great detail. When Buddhism was introduced into Japan, it had to contend with the beliefs and traditions that were already in place. But because Buddhism is centered on the individual’s path to enlightenment rather than on a deity, it was able to blend and coexist with other traditions. -

Tea Ceremony.Pptx

Tea Ceremony Orgins Japanese tea ceremony, or chanoyu , came about when Japan adopted both Chinese practices of drinking powdered green tea and Zen Buddhist beliefs. The traditional Japanese tea ceremony became more than just drinking tea; it is a spiritual experience that embodies harmony, respect, purity and tranquility. Steps of a formal tea ceremony Before a Japanese tea ceremony begins, guests may stay in a waiting room (machiai in Japanese) until the host is ready for them. The guests will walk across roji, Japanese for dewy ground, symbolically ridding themselves of the dust of the world in preparation for the ceremony. Then, the guests will wash their hands and mouths from water in a stone basin (tsukubai in Japanese) as a last purifying step. The host receives the guests through a small door or gate which is short, forcing the guests to bow upon entry. The host greets each guest with a silent bow. For an informal gathering, or chakai, guests are served Wagashi (sweets) and then the tea. Alternatively, a full three course meal is first served for a formal Japanese tea ceremony, known as chaji. This type of ceremony, complete with sake and intermission before the tea is served, can take up to four hours. The Japanese tea ceremony steps begin with cleaning and preparation of the tea serving utensils. The host cleans the tea bowl, tea scoop, and tea whisk with concentrated and graceful movements. Next, the host prepares the tea by adding three scoops of matcha green tea powder per guest to the tea bowl. Hot water is ladled into the bowl and whisked into a thin paste.