Zen and the Art of Tea Alyssa Penrod

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Pyrrhonism As a Sect of Buddhism? a Case Study in the Methodology of Comparative Philosophy

Comparative Philosophy Volume 9, No. 2 (2018): 1-40 Open Access / ISSN 2151-6014 www.comparativephilosophy.org EARLY PYRRHONISM AS A SECT OF BUDDHISM? A CASE STUDY IN THE METHODOLOGY OF COMPARATIVE PHILOSOPHY MONTE RANSOME JOHNSON & BRETT SHULTS ABSTRACT: We offer a sceptical examination of a thesis recently advanced in a monograph published by Princeton University Press entitled Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. In this dense and probing work, Christopher I. Beckwith, a professor of Central Eurasian studies at Indiana University, Bloomington, argues that Pyrrho of Elis adopted a form of early Buddhism during his years in Bactria and Gandhāra, and that early Pyrrhonism must be understood as a sect of early Buddhism. In making his case Beckwith claims that virtually all scholars of Greek, Indian, and Chinese philosophy have been operating under flawed assumptions and with flawed methodologies, and so have failed to notice obvious and undeniable correspondences between the philosophical views of the Buddha and of Pyrrho. In this study we take Beckwith’s proposal and challenge seriously, and we examine his textual basis and techniques of translation, his methods of examining passages, his construal of problems and his reconstruction of arguments. We find that his presuppositions are contentious and doubtful, his own methods are extremely flawed, and that he draws unreasonable conclusions. Although the result of our study is almost entirely negative, we think it illustrates some important general points about the methodology of comparative philosophy. Keywords: adiaphora, anātman, anattā, ataraxia, Buddha, Buddhism, Democritus, Pāli, Pyrrho, Pyrrhonism, Scepticism, trilakṣaṇa 1. INTRODUCTION One of the most ambitious recent works devoted to comparative philosophy is Christopher Beckwith’s monograph Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia (2015). -

The Path to Bodhidharma

The Path to Bodhidharma The teachings of Shodo Harada Roshi 1 Table of Contents Preface................................................................................................ 3 Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice ..................................................... 5 Zazen ................................................................................................ 52 Hakuin and His Song of Zazen ......................................................... 71 Sesshin ........................................................................................... 100 Enlightenment ................................................................................. 115 Work and Society ............................................................................ 125 Kobe, January 1995 ........................................................................ 139 Questions and Answers ................................................................... 148 Glossary .......................................................................................... 174 2 Preface Shodo Harada, the abbot of Sogenji, a three-hundred-year-old Rinzai Zen Temple in Okayama, Japan, is the Dharma heir of Yamada Mumon Roshi (1890-1988), one of the great Rinzai masters of the twentieth century. Harada Roshi offers his teachings to everyone, ordained monks and laypeople, men and women, young and old, from all parts of the world. His students have begun more than a dozen affiliated Zen groups, known as One Drop Zendos, in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The material -

THE Buddhist Thinker and Reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) Is Consid

J/Orient/03 03.10.10 10:55 AM ページ 94 A History of Women in Japanese Buddhism: Nichiren’s Perspectives on the Enlightenment of Women Toshie Kurihara OVERVIEW HE Buddhist thinker and reformer Nichiren (1222–1282) is consid- Tered among the most progressive of the founders of Kamakura Bud- dhism, in that he consistently championed the capacity of women to achieve salvation throughout his ecclesiastic writings.1 This paper will examine Nichiren’s perspectives on women, shaped through his inter- pretation of the 28-chapter Lotus Sutra of Gautama Shakyamuni in India, a version of the scripture translated by Buddhist scholar Kumara- jiva from Sanskrit to Chinese in 406. The paper’s focus is twofold: First, to review doctrinal issues concerning the spiritual potential of women to attain enlightenment and Nichiren’s treatises on these issues, which he posited contrary to the prevailing social and religious norms of medieval Japan. And second, to survey the practical solutions that Nichiren, given the social context of his time, offered to the personal challenges that his women followers confronted in everyday life. THE ATTAINMENT OF BUDDHAHOOD BY WOMEN Historical Relationship of Women and Japanese Buddhism During the Middle Ages, Buddhism in Japan underwent a significant transformation. The new Buddhism movement, predicated on simpler, less esoteric religious practices (igyo-do), gained widespread acceptance among the general populace. It also redefined the roles that women occupied in Buddhism. The relationship between established Buddhist schools and women was among the first to change. It is generally acknowledged that the first three individuals in Japan to renounce the world and devote their lives to Buddhist practice were women. -

Mahayana Buddhism: the Doctrinal Foundations, Second Edition

9780203428474_4_001.qxd 16/6/08 11:55 AM Page 1 1 Introduction Buddhism: doctrinal diversity and (relative) moral unity There is a Tibetan saying that just as every valley has its own language so every teacher has his own doctrine. This is an exaggeration on both counts, but it does indicate the diversity to be found within Buddhism and the important role of a teacher in mediating a received tradition and adapting it to the needs, the personal transformation, of the pupil. This divers- ity prevents, or strongly hinders, generalization about Buddhism as a whole. Nevertheless it is a diversity which Mahayana Buddhists have rather gloried in, seen not as a scandal but as something to be proud of, indicating a richness and multifaceted ability to aid the spiritual quest of all sentient, and not just human, beings. It is important to emphasize this lack of unanimity at the outset. We are dealing with a religion with some 2,500 years of doctrinal development in an environment where scho- lastic precision and subtlety was at a premium. There are no Buddhist popes, no creeds, and, although there were councils in the early years, no attempts to impose uniformity of doctrine over the entire monastic, let alone lay, establishment. Buddhism spread widely across Central, South, South-East, and East Asia. It played an important role in aiding the cultural and spiritual development of nomads and tribesmen, but it also encountered peoples already very culturally and spiritually developed, most notably those of China, where it interacted with the indigenous civilization, modifying its doctrine and behaviour in the process. -

Speech by Ōno Genmyō, Head Priest of the Horyu-Ji Temple “Shōtoku Taishi and Horyu-Ji” (October 20, 2018, Shinjuku-Ku, Tokyo)

Speech by Ōno Genmyō, Head Priest of the Horyu-ji Temple “Shōtoku Taishi and Horyu-ji” (October 20, 2018, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo) MC Ladies and gentlemen, thank you for coming today. The town of Ikaruga, where the Horyu-ji Temple is located, is very conveniently located: just 10 minutes by JR from Nara, 20 minutes from Tennoji in Osaka, and 80 minutes from Kyoto. This historical area is home to sites that include the Horyu-ji , the Horin-ji, the Hkki-ji, the Chugu- ji, and the Fujinoki Kofun tumulus. The Reverend Mr. Ōno will be speaking with us today in detail about the Horyu-ji, which was founded in 607 by Shotoku Taishi, Prince Shotoku, a member of the imperial family. As it is home to the oldest wooden building in the world, it was the first site in Japan to be registered as a World Heritage property. However, its attractions go beyond the buildings. While Kyoto temples are famous for their gardens, Nara’s attractions are, more than anything, its Buddhist sculptures. The Horyu-ji is home to some of Japan’s most noted Buddhist statues, including the Shaka Sanzon [Shaka Triad of Buddha and Two Bosatsu], the Kudara Kannon, Yakushi Nyorai, and Kuse Kannon. Prince Shotoku was featured on the 10,000 yen bill until 1986, so there may even be people overseas who know of him. Shotoku was the creator of Japan’s first laws and bureaucratic system, a proponent of relations with China, and incorporated Buddhism into politics. Reverend Ōno, if you would be so kind. -

Thought and Practice in Mahayana Buddhism in India (1St Century B.C. to 6Th Century A.D.)

International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. ISSN 2250-3226 Volume 7, Number 2 (2017), pp. 149-152 © Research India Publications http://www.ripublication.com Thought and Practice in Mahayana Buddhism in India (1st Century B.C. to 6th Century A.D.) Vaishali Bhagwatkar Barkatullah Vishwavidyalaya, Bhopal (M.P.) India Abstract Buddhism is a world religion, which arose in and around the ancient Kingdom of Magadha (now in Bihar, India), and is based on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama who was deemed a "Buddha" ("Awakened One"). Buddhism spread outside of Magadha starting in the Buddha's lifetime. With the reign of the Buddhist Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, the Buddhist community split into two branches: the Mahasaṃghika and the Sthaviravada, each of which spread throughout India and split into numerous sub-sects. In modern times, two major branches of Buddhism exist: the Theravada in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and the Mahayana throughout the Himalayas and East Asia. INTRODUCTION Buddhism remains the primary or a major religion in the Himalayan areas such as Sikkim, Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh, the Darjeeling hills in West Bengal, and the Lahaul and Spiti areas of upper Himachal Pradesh. Remains have also been found in Andhra Pradesh, the origin of Mahayana Buddhism. Buddhism has been reemerging in India since the past century, due to its adoption by many Indian intellectuals, the migration of Buddhist Tibetan exiles, and the mass conversion of hundreds of thousands of Hindu Dalits. According to the 2001 census, Buddhists make up 0.8% of India's population, or 7.95 million individuals. Buddha was born in Lumbini, in Nepal, to a Kapilvastu King of the Shakya Kingdom named Suddhodana. -

Teahouses and the Tea Art: a Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie Master's Thesis in East Asian Culture and History (EAST4591 – 60 Credits – Autumn 2015) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF OSLO 24 November, 2015 © LI Jie 2015 Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie http://www.duo.uio.no Print: University Print Center, University of Oslo II Summary The subject of this thesis is tradition and the current trend of tea culture in China. In order to answer the following three questions “ whether the current tea culture phenomena can be called “tradition” or not; what are the changes in tea cultural tradition and what are the new features of the current trend of tea culture; what are the endogenous and exogenous factors which influenced the change in the tea drinking tradition”, I did literature research from ancient tea classics and historical documents to summarize the development history of Chinese tea culture, and used two month to do fieldwork on teahouses in Xi’an so that I could have a clear understanding on the current trend of tea culture. It is found that the current tea culture is inherited from tradition and changed with social development. Tea drinking traditions have become more and more popular with diverse forms. -

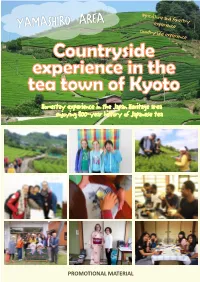

Enjoying 800-Year History of Japanese Tea

Homestay experience in the Japan Heritage area enjoying 800-year history of Japanese tea PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL ●About Yamashiro area The area of the Japanese Heritage "A walk through the 800-year history of Japanese tea" Yamashiro area is in the southern part of Kyoto Prefecture and famous for Uji Tea, the exquisite green tea grown in the beautiful mountains. Beautiful tea fields are covering the mountains, and its unique landscape with houses and tea factories have been registered as the Japanese Heritage “A Walk through the 800-year History of Japanese Tea". Wazuka Town and Minamiyamashiro Village in Yamashiro area produce 70% of Kyoto Tea, and the neighborhood Kasagi Town offers historic sightseeing places. We are offering a countryside homestay experience in these towns. わづかちょう 和束町 WAZUKA TOWN Tea fields in Wazuka Tea is an evergreen tree from the camellia family. You can enjoy various sceneries of the tea fields throughout the year. -1- かさぎちょう 笠置町 KASAGI TOWN みなみやましろむら 南山城村 MINAMI YAMASHIRO VILLAGE New tea leaves / Spring Early rice harvest / Autumn Summer Pheasant Tea flower / Autumn Memorial service for tea Persimmon and tea fields / Autumn Frosty tea field / Winter -2- ●About Yamashiro area Countryside close to Kyoto and Nara NARA PARK UJI CITY KYOTO STATION OSAKA (40min) (40min) (a little over 1 hour) (a little over 1 hour) The Yamashiro area is located one hour by car from Kyoto City and Osaka City, and it is located 30 to 40 minutes from Uji City and Nara City. Since it is surrounded by steep mountains, it still remains as country side and we have a simple country life and abundant nature even though it is close to the urban area. -

Utilization of 'Urni' in Our Daily Life

International Journal of Research p-ISSN: 2348-6848 e-ISSN: 2348-795X Available at https://edupediapublications.org/journals Volume 03 Issue 12 August 2016 Utilization of ‘Urni’ in Our Daily Life Mr. Ashis Kumar Pradhan1, Dr. Subimalendu Bikas Sinha 2 1Research Scholar, Bhagwant University, Ajmer, Rajasthan, India 2 Emeritus Fellow, U.G.C and Ex Principal, Indian college arts & Draftsmanship, kolkata “Urni‟ is manufactured by few weaving Abstract techniques with different types of clothing. It gained ground as most essential and popular „Urni‟ is made by cotton, silk, lilen, motka, dress material. Starting in the middle of the tasar & jute. It is used by men and women. second millennium BC, Indo-European or „Urni‟ is an unstitched and uncut piece of cloth Aryan tribes migrated keen on North- Western used as dress material. Yet it is not uniformly India in a progression of waves resulting in a similar in everywhere it is used. It differs in fusion of cultures. This is the very juncture variety, form, appearance, utility, etc. It bears when latest dynasties were formed follow-on the identity of a country, region and time. the flourishing of clothing style of which the „Urni‟ was made in different types and forms „Urni‟ type was a rarely main piece. „Urni‟ is a for the use of different person according to quantity of fabric used as dress material in position, rank, purpose, time and space. Along ancient India to cover the upper part of the with its purpose as dress material it bears body. It is used to hang from the neck to drape various religious values, royal status, Social over the arms, and can be used to drape the position, etc. -

Zen) Buddhism

THE SPREAD OF CHAN (ZEN) BUDDHISM T. Grif\ th Foulk (Sarah Lawrence College, New York) 1. Introduction This chapter deals with the development and spread of the so-called Chan School of Buddhism in China, Japan, and the West. In its East Asian setting, at least, the spread of Chan must be viewed rather dif- ferently than the spread of Buddhism as a whole, for by all accounts (both traditional and modern) Chan was a movement that initially ] ourished within, or (as some would have it) in reaction against, a Buddhist monastic order that had already been active in China for a number of centuries. By the same token, at the times when the Chan movement spread to Korea and Japan, it did not appear as the har- binger of Buddhism itself, which was already well established in those countries, but rather as the most recent in a series of importations of Buddhism from China. The situation in the West, of course, is much different. Here, Chan—usually referred to (using the Japanese pronun- ciation) as Zen—has indeed been at the vanguard of the spread of Buddhism as a whole. I begin this chapter by re] ecting on what we (modern scholars) mean when we speak of the spread of Buddhism, contrasting that with a few of the traditional ways in which Asian Buddhists themselves, from an insider’s or normative point of view, have conceived the transmission of the Buddha’s teachings (Skt. buddhadharma, Chin. fofa 佛法). I then turn to the main topic: the spread of Chan. -

Theravada Buddhism and Dai Identity in Jinghong, Xishuangbanna James Granderson SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2015 Theravada Buddhism and Dai Identity in Jinghong, Xishuangbanna James Granderson SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Granderson, James, "Theravada Buddhism and Dai Identity in Jinghong, Xishuangbanna" (2015). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2070. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2070 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Theravada Buddhism and Dai Identity in Jinghong, Xishuangbanna Granderson, James Academic Director: Lu, Yuan Project Advisors:Fu Tao, Michaeland Liu Shuang, Julia (Field Advisors), Li, Jing (Home Institution Advisor) Gettysburg College Anthropology and Chinese Studies China, Yunnan, Xishuangbanna, Jinghong Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for China: Language, Cultures and Ethnic Minorities, SIT Study Abroad, Spring 2015 I Abstract This ethnographic field project focused upon the relationship between the urban Jinghong and surrounding rural Dai population of lay people, as well as a few individuals from other ethnic groups, and Theravada Buddhism. Specifically, I observed how Buddhism manifests itself in daily urban life, the relationship between Theravada monastics in city and rural temples and common people in daily life, as well as important events wherelay people and monastics interacted with one another. -

Japanese Tea Ceremony: How It Became a Unique Symbol of the Japanese Culture and Shaped the Japanese Aesthetic Views

International J. Soc. Sci. & Education 2021 Vol.11 Issue 1, ISSN: 2223-4934 E and 2227-393X Print Japanese Tea Ceremony: How it became a unique symbol of the Japanese culture and shaped the Japanese aesthetic views Yixiao Zhang Hangzhou No.2 High School of Zhejiang Province, CHINA. [email protected] ABSTRACT In the process of globalization and cultural exchange, Japan has realized a host of astonishing achievements. With its unique cultural identity and aesthetic views, Japan has formed a glamorous yet mysterious image on the world stage. To have a comprehensive understanding of Japanese culture, the study of Japanese tea ceremony could be of great significance. Based on the historical background of Azuchi-Momoyama period, the paper analyzes the approaches Sen no Rikyu used to have the impact. As a result, the impact was not only on the Japanese tea ceremony itself, but also on Japanese culture and society during that period and after.Research shows that Tea-drinking was brought to Japan early in the Nara era, but it was not integrated into Japanese culture until its revival and promotion in the late medieval periods under the impetus of the new social and religious realities of that age. During the Azuchi-momoyama era, the most significant reform took place; 'Wabicha' was perfected by Takeno Jouo and his disciple Sen no Rikyu. From environmental settings to tea sets used in the ritual to the spirit conveyed, Rikyu reregulated almost all aspects of the tea ceremony. He removed the entertaining content of the tea ceremony, and changed a rooted aesthetic view of Japanese people.