Japan Studies Association Journal, 2001. INSTITUTION Japan Studies Association, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOT TYPESET LOW HIGH 7000 German Porcelain Figural Group

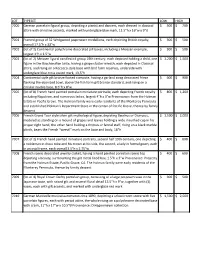

LOT TYPESET LOW HIGH 7000 German porcelain figural group, depicting a pianist and dancers, each dressed in classical $ 500 $ 700 attire with crinoline accents, marked with underglaze blue mark, 11.5"h x 16"w x 9"d 7001 Framed group of 32 Wedgwood jasperware medallions, each depicting British royalty, $ 300 $ 500 overall 17.5"h x 33"w 7002 (lot of 2) Continental polychrome decorated pill boxes, including a Meissen example, $ 300 $ 500 largest 1"h x 2.5"w 7003 (lot of 2) Meissen figural candlestick group 19th century, each depicted holding a child, one $ 1,200 $ 1,500 figure in the Bacchanalian taste, having a grape cluster wreath, each depicted in Classical attire, and rising on a Rococco style base with bird form reserves, underside with underglaze blue cross sword mark, 13,5"h 7004 Continental style gilt bronze footed compote, having a garland swag decorated frieze $ 600 $ 900 flanking the ebonized bowl, above the fish form gilt bronze standard, and rising on a circular marble base, 8.5"h x 8"w 7005 (lot of 8) French hand painted porcelain miniature portraits; each depicting French royalty $ 800 $ 1,200 including Napoleon, and numerous ladies, largest 4"h x 3"w Provenance: from the Holman Estate in Pacific Grove. The Holman family were early residents of the Monterey Peninsula and established Holman's Department Store in the center of Pacific Grove, thence by family descent 7006 French Grand Tour style silver gilt mythological figure, depicting Bacchus or Dionysus, $ 1,500 $ 2,000 modeled as standing on a mound of grapes and leaves holding -

Japanese Immigration History

CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) By HOSOK O Bachelor of Arts in History Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 2000 Master of Arts in History University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2010 © 2010, Hosok O ii CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) Dissertation Approved: Dr. Ronald A. Petrin Dissertation Adviser Dr. Michael F. Logan Dr. Yonglin Jiang Dr. R. Michael Bracy Dr. Jean Van Delinder Dr. Mark E. Payton Dean of the Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For the completion of my dissertation, I would like to express my earnest appreciation to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Ronald A. Petrin for his dedicated supervision, encouragement, and great friendship. I would have been next to impossible to write this dissertation without Dr. Petrin’s continuous support and intellectual guidance. My sincere appreciation extends to my other committee members Dr. Michael Bracy, Dr. Michael F. Logan, and Dr. Yonglin Jiang, whose intelligent guidance, wholehearted encouragement, and friendship are invaluable. I also would like to make a special reference to Dr. Jean Van Delinder from the Department of Sociology who gave me inspiration for the immigration study. Furthermore, I would like to give my sincere appreciation to Dr. Xiaobing Li for his thorough assistance, encouragement, and friendship since the day I started working on my MA degree to the completion of my doctoral dissertation. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Exponent of Breath: The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan's Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/32d241sf Author Perelman, Elisheva Avital Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Exponent of Breath: The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan’s Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century By Elisheva Avital Perelman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Andrew E. Barshay, Chair Professor John Lesch Professor Alan Tansman Fall 2011 © Copyright by Elisheva Avital Perelman 2011 All Rights Reserved Abstract The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan’s Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century By Elisheva Avital Perelman Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Andrew E. Barshay, Chair Tuberculosis existed in Japan long before the arrival of the first medical missionaries, and it would survive them all. Still, the epidemic during the period from 1890 until the 1920s proved salient because of the questions it answered. This dissertation analyzes how, through the actions of the government, scientists, foreign evangelical leaders, and the tubercular themselves, a nation defined itself and its obligations to its subjects, and how foreign evangelical organizations, including the Young Men’s Christian Association (the Y.M.C.A.) and The Salvation Army, sought to utilize, as much as to assist, those in their care. -

Notes Toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo

The Shrine : Notes toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo By A.W. S a d l e r Sarah Lawrence College When I arrived in Japan in the autumn of 1965, I settled my family into our home-away-from-home in a remote comer of Bunkyo-ku3 in Tokyo, and went to call upon an old timer,a man who had spent most of his adult life in Tokyo. I told him of my intention to carry out an exhaustive study of the annual festivals (taisai) of a typical neighbor hood shrine (jinja) in my area of residence,and I told him I had a full year at my disposal for the task. “Start on the grounds of the shrine/,was his solid advice; “go over every tsubo '(every square foot3 we might say),take note of every stone, investigate every marker.” And that is how I began. I worked with the shrines closest to home so that shrine and people would be part of my everyday life. When my wife and I went for an evening stroll, we invariably happened upon the grounds of one of our shrines; when we went to the market for fish or pencils or raaisnes we found ourselves visiting with the ujiko (parishioners; literally,children of the god of the shrine, who is guardian spirit of the neighborhood) of the shrine. I started with five shrines. I had great difficulty arranging for interviews with the priests of two of the five (the reasons for their reluc tance to visit with me will be discussed below) ; one was a little too large and famous for my purposes,and another was a little too far from home for really careful scrutiny. -

Joseph Heco and the Origin of Japanese Journalism*

Journalism and Mass Communication, Mar.-Apr. 2020, Vol. 10, No. 2, 89-101 doi: 10.17265/2160-6579/2020.02.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING Joseph Heco and the Origin of Japanese Journalism* WANG Hai, YU Qian, LIANG Wei-ping Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, China Joseph Heco, with the original Japanese name of Hamada Hikozo, played an active role in the diplomatic, economic, trade, and cultural interactions between the United States and Japan in the 1850s and 1860s. Being rescued from a shipwreck by an American freighter and taken to San Francisco in the 1850s, Heco had the chance to experience the advanced industrial civilization. After returning to Japan, he followed the example of the U.S. newspapers to start the first Japanese newspaper Kaigai Shimbun (Overseas News), introducing Western ideas into Japan and enabling Japanese people under the rule of the Edo bakufu/shogunate to learn about the great changes taking place outside the island. In the light of the historical background of the United States forcing Japan to open up, this paper expounds on Joseph Heco’s life experience and Kaigai Shimbun, the newspaper he founded, aiming to explain how Heco, as the “father of Japanese journalism”, promoted the development of Japanese newspaper industry. Keywords: Joseph Heco (Hamada Hikozo), Kaigai Shimbun, origin of Japanese journalism Early Japanese newspapers originated from the “kawaraban” (瓦版) at the beginning of the 17th century. In 1615, this embryonic form of newspapers first appeared in the streets of Osaka. This single-sided leaflet-like thing was printed irregularly and was made by printing on paper with tiles which was carved with pictures and words and then fired and shaped. -

The Foreign Service Journal, April 1961

*r r" : • »■! S Journal Service Foreign POWERFUL WRITTEN SWARTZDid you write for the new catalogue? 600 South Pulaski Street, Baltimore 23. INCREDIBLE is understating the power of the burgeoning NATURAL SHOULDER suit line (for fall 1961-62 whose delivery begins very soon.) Premium machine (NOT hand-needled) it has already induced insomnia among the $60 to $65 competitors—(with vest $47.40) coat & pant Today, the success or failure of statesmen, businessmen and industrialists is often determined by their A man knowledge of the world’s fast-changing scene. To such men, direct news and information of events transpiring anywhere in the world is of vital necessity. It ivho must know influences their course of action, conditions their judgement, solidifies their decisions. And to the most successful of what’s going on these men, the new all-transistor Zenith Trans-Oceanic portable radio has proved itself an invaluable aide. in the world For the famous Zenith Trans-Oceanic is powered to tune in the world on 9 wave bands . including long wave ... counts on the new and Standard Broadcast, with two continuous tuning bands from 2 to 9 MC, plus bandspread on the 31,25,19,16 and 13 meter international short wave bands. And it works on low-cost flashlight batteries available anywhere. No need for AC/DC power outlets or “B” batteries! ZENITH You can obtain the Zenith Trans-Oceanic anywhere in the free world, but write — if necessary — for the name of your nearest dealer. And act now if you’re a man all-transistor who must know what’s going on in the world — whether you’re at work, at home, at play or traveling! TRANS-OCEAN: world’s most magnificent radio! The Zenith Trans-Oceanic is the only radio of its kind in the world! Also available, without the long wave band, as Model Royal 1000. -

Acta Asiatica Varsoviensia No. 27 Acta Asiatica Varsoviensia

ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA NO. 27 ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA Editor-in-Chief Board of Advisory Editors MARIA ROMAN S£AWIÑSKI NGUYEN QUANG THUAN KENNETH OLENIK Subject Editor ABDULRAHMAN AL-SALIMI OLGA BARBASIEWICZ JOLANTA SIERAKOWSKA-DYNDO BOGDAN SK£ADANEK Statistical Editor LEE MING-HUEI MARTA LUTY-MICHALAK ZHANG HAIPENG Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures Polish Academy of Sciences ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA NO. 27 ASKON Publishers Warsaw 2014 Secretary Nicolas Levi English Text Consultant James Todd © Copyright by Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw 2014 Printed in Poland This edition prepared, set and published by Wydawnictwo Naukowe ASKON Sp. z o.o. Stawki 3/1, 00193 Warszawa tel./fax: (+48) 22 635 99 37 www.askon.waw.pl [email protected] PL ISSN 08606102 ISBN 978837452080–5 ACTA ASIATICA VARSOVIENSIA is abstracted in The Central European Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Index Copernicus To the memory of Professor Karin Tomala Whom we lost for ever Contents ARTICLES OLGA BARBASIEWICZ, The Cooperation of Jacob Schiff and Takahashi Korekiyo Regarding the Financial Support for the War with Russia (19041905). Analysis of Schiff and Takahashis Private Correspondence and Diaries ............................................................................ 9 KAROLINA BROMA-SMENDA, Enjo-kôsai (compensated dating) in Contemporary Japanese Society as Seen through the Lens of the Play Call Me Komachi ....................................................................... -

Confidential US State Department Special Files

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Confidential U.S. State Department Special Files RECORDS OF THE OFFICE OF THE ASSISTANT LEGAL ADVISER FOR EDUCATIONAL, CULTURAL, AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS Part 1: Records on the Disposition of German Assets A UPA Collection from Confidential U.S. State Department Special Files RECORDS OF THE OFFICE OF THE ASSISTANT LEGAL ADVISER FOR EDUCATIONAL, CULTURAL, AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS Part 1: Records on the Disposition of German Assets Lot File 96D269 Project Editor Robert E. Lester Guide Compiled by Daniel Lewis The documents reproduced in this publication are among the records of the U.S. Department of State in the custody of the National Archives of the United States. No copyright is claimed in these official U.S. government records. A UPA Collection from 7500 Old Georgetown Road • Bethesda, MD 20814-6126 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Records of the Office of the Assistant Legal Adviser for Educational, Cultural, and Public Affairs [microform] / project editor, Robert E. Lester. microfilm reels. Reproduces records of the U.S. Department of State in the custody of the National Archives of the United States. Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Daniel Lewis. ISBN 1-55655-979-8 (part 1) — ISBN 0-88692-673-4 (part 2) — ISBN 0-88692-674-2 (part 3) 1. World War, 1939–1945—Confiscations and contributions—Europe. 2. World War, 1939–1945—Reparations. 3. Jews—Europe—Claims. 4. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)— Reparations. I. Lester, Robert. II. Lewis, Daniel, 1972– . III. United States. Dept. of State. D810.C8 940.54'05—dc22 2005044129 CIP Copyright © 2005 LexisNexis, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. -

The Foreign Service Journal, May 1944

giu AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE VOL. 21, NO. 5 JOURNAL MAY, 1944 WHEN YOU SAY WHISKEY WHEN YOU INSIST ON THREE FEATHERS Today American whiskey is the vogue Headwaiters are not the only weathervanes of the increasing popularity of American whiskies throughout the world. Wherever smart people gather, whiskies made in the U. S. A. are more and more in evidence. This is not a brand-new trend. Actually, for many years past, world sales of American whiskies have topped those of all whiskies made elsewhere. Your patronage has exceptional importance in maintaining this momentum. We recommend to your attention THREE FEATHERS, a mellow, slowly aged, friendly whiskey that is outstanding even among American whiskies. OLDETYME DISTILLERS CORPORATION EMPIRE STATE BUILDING, NEW YORK THREE FEATHERS THE AMERICAN WHISKEY PAR EXCELLENCE This rallying cry is appearing In Schen/ey advertising throughout Latin America ... LIBER CONTENTS MAY, 1944 Cover Picture: Transcontinental circuits being: buried at the foot of Christ of the Andes. Report of the Internment and Repatriation of the Official American Group in France 229 By Woodruff W(diner A Century of Progress in Telecommunications.... 233 By Francis Colt de Wolf Sweden’s “Fortress of Education” 236 By Hallett Johnson Edmonton Points North 238 By Robert English Letter from Naples 240 Protective Association Announcement 241 Births 241 ALSO WIN WARS In Memoriam 241 Marriages 241 During 1943, the men and women of Douglas Aircraft contributed 40,164 Editors’ Column 242 ideas designed to save time, effort Letters to the Editors 243 and material in building warplanes. News from the Department 244 These ideas proved of great value By Jane Wilson in increasing output of all three News from the Field 247 types of 4-engine landplanes as well The Bookshelf 249 as dive bombers, attack bombers, Francis C. -

Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah: the Origins of Iranian Primacy in the Persian Gulf

Roham Alvandi Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah: the origins of Iranian primacy in the Persian Gulf Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Alvandi, Roham (2012) Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah: the origins of Iranian primacy in the Persian Gulf. Diplomatic history, 36 (2). pp. 337-372. ISSN 1467-7709 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-7709.2011.01025.x © 2012 The Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations (SHAFR) This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/32743/ Available in LSE Research Online: March 2012 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript accepted version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the published version may remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. roham alvandi Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah: The Origins of Iranian Primacy in the Persian Gulf* On the morning of May 31, 1972, the shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, received U.S. -

Japanese Garden

満開 IN BLOOM A PUBLICATION FROM WATERFRONT BOTANICAL GARDENS SPRING 2021 A LETTER FROM OUR 理事長からの PRESIDENT メッセージ An opportunity was afforded to WBG and this region Japanese Gardens were often built with tall walls or when the stars aligned exactly two years ago! We found hedges so that when you entered the garden you were out we were receiving a donation of 24 bonsai trees, the whisked away into a place of peace and tranquility, away Graeser family stepped up with a $500,000 match grant from the worries of the world. A peaceful, meditative to get the Japanese Garden going, and internationally garden space can teach us much about ourselves and renowned traditional Japanese landscape designer, our world. Shiro Nakane, visited Louisville and agreed to design a two-acre, authentic Japanese Garden for us. With the building of this authentic Japanese Garden we will learn many 花鳥風月 From the beginning, this project has been about people, new things, both during the process “Kachou Fuugetsu” serendipity, our community, and unexpected alignments. and after it is completed. We will –Japanese Proverb Mr. Nakane first visited in September 2019, three weeks enjoy peaceful, quiet times in the before the opening of the Waterfront Botanical Gardens. garden, social times, moments of Literally translates to Flower, Bird, Wind, Moon. He could sense the excitement for what was happening learning and inspiration, and moments Meaning experience on this 23-acre site in Louisville, KY. He made his of deep emotion as we witness the the beauties of nature, commitment on the spot. impact of this beautiful place on our and in doing so, learn children and grandchildren who visit about yourself. -

Newsletter 13 (June 2014)

June 2014 - Volume 6 - Issue 2 June 2014 - Volume 6 - Issue 2 国際基督教大学ロータリー平和センター ニューズレター ICU Rotary Peace Center Newsletter Rotary Peace Center Staff Director: Masaki Ina Associate Director: Giorgio Shani G.S. Office Manager: Masako Mitsunaga Coordinator: Satoko Ohno Contact Information: Rotary Peace Center International Christian University 3-10-2 Osawa, Mitaka, Tokyo 181-8585 Tel: +81 422 33 3681 Fax: +81 422 33 3688 [email protected] http://subsite.icu.ac.jp/rotary/ Index In this issue: 2 - Trailblazing Events 4 - Preparing For Peace 5 - Experiential Learning Reflections 7 - Meet The Families of Class XII Fellows 10 - Class XI Thesis Summaries 15 - Class XII AFE Placements 16 - Gratitude and Appreciation from Class XII 1 Trailblazing Events ICU Celebrates First Ever Black History Month by Nixon Nembaware Being an International University, ICU brings together students and Faculty members of various backgrounds and races. It is thus a suitable place to cultivate understanding of different cultures and heritages. This was the thinking that Rotary Peace Fellow Class XII had in mind when they partnered with the Social Science Research Institute to celebrate the first ever Black History Month commemoration at ICU. Two main events were lined up, first was a dialogue with Dr. Mohau Pheko, Ambassador of the Republic of South Africa to Japan who visited our campus to give an open lecture on the legacy of ‘Nelson Mandela’ and the history of black people in South Africa. Second was a dialogue with Ms. Judith Exavier, Ambassador of the Republic of Haiti to Japan. She talked of the history of the black people in the Caribbean Island and linked the history of slavery to what prospects lie ahead for black people the world over.