From Sultan Mahmud Ii to Sultan Mehmed Vi Vahdeddn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

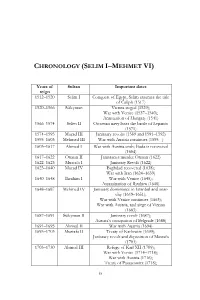

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I 76-3459 HYMES, John David, Jr.,1942- the CONTRIBUTION of DR

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is avily hi dependent upon the.quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of tichniquesti is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they ^re spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the Imf is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposureand thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the ph otographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the materi <il. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — begi Hning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indiicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat Ijigher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essent al to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Hanedân-I Saltanat Nizamnamesi Ve Uygulanmasi Cevdet Kirpik*

HANEDÂN-I SALTANAT NIZAMNAMESI VE UYGULANMASI CEVDET KIRPIK* Giri~~ Osmanl~~ hanedan üyelerinin sosyal hayat~n~, ya~ay~~~m ve aile huku- kuyla ilgili baz~~ meselelerini düzenleyen ilk nizamname 16 Kas~m 1913 tari- hinde ç~kar~ld~. Nizamname, hanedan azas~n~~ ilgilendiren birçok meseleyi etrafl~ca ele almaktayd~. Düzenlemede yer alan hususlar~n önemli bir k~sm~~ teamül-ü kadimden olup baz~lar~~ ise kendi devrinde ortaya ç~kan bir tak~m sorunlar~n çözümüne yönelik yeni konulard~. Yüzy~llar boyu belirli geleneklerin ~~~~~nda ya~ay~p giden Osmanl~~ ha- nedarnyla ilgili bir nizamname ç~karmay~~ gerekli k~lan sebepler nelerdi? Nizamname kimler tarafindan, niçin haz~rland~, içeri~inde neler vard~~ ve en önemlisi de nas~l uyguland~? Hanedân-~~ Saltanat ~izâs~n~n~~ Hâl ve Mevkileri ile Vazâifini Tayin Eden Nizamnâme ad~yla haz~rlanan Nizamname, padi~ah~n 16 Kas~m 1913 tarih ve 243 say~l~~ iradesiyle yürürlü~e girdi2. Nizamname, kanun mahiyetinde düzenlenmedi~inden Meclis-i Meb'ilsân ve Meclis-i Ayân'da müzakere edilmemi~, dolay~s~yla da esbâb-~~ Erciyes Üniversitesi, E~itim Fakültesi Ö~retim Üyesi. Hanedan-1 saltanat ~izlis~ndan kas~t; padi~ah, ~ehzadeler ve onlar~n k~z ve erkek çoculdar~d~r. Ni- tekim bu husus Hanedan-1 Abi Osman Umüru Hakk~nda Kararname'de padi~ah ve ~ehzadelerin hanedan sicilinde kay~ tl~~ zevceleri ile sultanlar~n k~z ve erkek çocuklar~~ ve e~leri "efrad-~~ hanedandan olmayub haned5n-1 saltanata mensup" olarak adland~r~lmaktayd~. BOA, Hanedan Defteri, No:2, s.60. Yine ~ehzade Ali Vas~b Efendi, hanedan mensuplar~~ ile dzds: aras~nda fark~~ ~u ~ekilde dile getirmekte- dir: "Haneclarum~zda erkek nesline verilen ehemmiyetin bariz i~aretlerinden biri, padi~ah veya ~eh- zade k~z~~ olan sultanlar~n çocuklar~n~ n hanedan azas~~ de~il, hanedan mensubu say~lmas~~ ve bu men- subiyetin kendi çocuklar~na intikal edememesidir." Ali Vas~b Efendi, Bir ~ehztule'nin Hdtirdt~~ Vatan ve Menfdda Gördid~lerim ve i~ittilderirn, Haz~rlayan: Osman Selaheddin Osmano~lu, ~stanbul, 2005, s.12. -

How Was the Traditional Makam Theory Westernized for the Sake of Modernization?

Rast Müzikoloji Dergisi, 2018, 6 (1): 1769-1787 Original research https://doi.org/10.12975/pp1769-1787 Özgün araştırma How was the traditional makam theory westernized for the sake of modernization? Okan Murat Öztürk Ankara Music and Fine Arts University, Department of Musicology, Ankara, Turkey [email protected] Abstract In this article, the transformative interventions of those who want to modernize the tradition- al makam theory in Westernization process experienced in Turkey are discussed in historical and critical context. The makam is among the most basic concepts of Turkish music as well as the Eastern music. In order to analyze the issue correctly in conceptual framework, here, two basic ‘music theory approaches' have been distinguished in terms of the musical elements they are based on: (i.) ‘scale-oriented’ and, (ii.) ‘melody-oriented’. The first typically represents the conception of Western harmonic tonality, while the second also represents the traditional Turkish makam conception before the Westernization period. This period is dealt with in three phases: (i.) the traditional makam concept before the ‘modernization’, (ii.) transformative interventions in the modernization phase, (iii.) recent new and critical approaches. As makam theory was used once in the history of Turkey, to convey a traditional heritage, it had a peculi- ar way of practice and education in its own cultural frame. It is determined that three different theoretical models based on mathematics, philosophy or composition had been used to explain the makams. In the 19th century, Turkish modernization was resulted in a stage in which a desire to ‘resemble to the West’ began to emerge. -

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor. -

US Risks Further Clashes As Syrian Boot Print Broadens News & Analysis

May 28, 2017 9 News & Analysis Syria US risks further clashes as Syrian boot print broadens Simon Speakman Cordall Tunis ondemnation, criticism and, inevitably, escalation have quickly followed a US air strike against an appar- ently Iranian-backed mili- Ctia convoy near Syria’s border with Jordan and Iraq. The clash has, at least, provided analysts with some indication of American aspirations in Syria and, as the United States increases its military commitment in the area, some indication of the risks it runs of banging heads with other interna- tional actors active on Syria’s battle- scarred ground. Fars reported, “thousands of Hezbollah troops were sent to al-Tanf passageway at Iraq- Syria bordering areas.” US commanders said the convoy of Iranian-supported militia ignored numerous calls for it to halt as it Not without risks. A US-backed Syrian fighter stands on a vehicle with heavy automatic machine gun (L) next to an American soldier moved towards coalition positions who stands on an armoured vehicle at the Syrian-Iraqi crossing border point of al-Tanf. (AP) at al-Tanf, justifying the strike that destroyed a number of vehicles and killed several militiamen. agency, referred to a British, Jorda- is the military is much more likely tion to the “several hundred” special the US decision to directly arm the However, for Iran and its allies in nian and US plot to create a buffer to improvise and this decision to hit operations troops present near ISIS’s Kurds and to conduct the air strike Moscow and Damascus, the strike zone in the area, like that at the Go- the regime may have been taken at de facto capital of Raqqa, gathering against Hezbollah forces threatening marked an aerial “aggression” by lan Heights and leading ultimately to the lower levels. -

1 the Turks and Europe by Gaston Gaillard London: Thomas Murby & Co

THE TURKS AND EUROPE BY GASTON GAILLARD LONDON: THOMAS MURBY & CO. 1 FLEET LANE, E.C. 1921 1 vi CONTENTS PAGES VI. THE TREATY WITH TURKEY: Mustafa Kemal’s Protest—Protests of Ahmed Riza and Galib Kemaly— Protest of the Indian Caliphate Delegation—Survey of the Treaty—The Turkish Press and the Treaty—Jafar Tayar at Adrianople—Operations of the Government Forces against the Nationalists—French Armistice in Cilicia—Mustafa Kemal’s Operations—Greek Operations in Asia Minor— The Ottoman Delegation’s Observations at the Peace Conference—The Allies’ Answer—Greek Operations in Thrace—The Ottoman Government decides to sign the Treaty—Italo-Greek Incident, and Protests of Armenia, Yugo-Slavia, and King Hussein—Signature of the Treaty – 169—271 VII. THE DISMEMBERMENT OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE: 1. The Turco-Armenian Question - 274—304 2. The Pan-Turanian and Pan-Arabian Movements: Origin of Pan-Turanism—The Turks and the Arabs—The Hejaz—The Emir Feisal—The Question of Syria—French Operations in Syria— Restoration of Greater Lebanon—The Arabian World and the Caliphate—The Part played by Islam - 304—356 VIII. THE MOSLEMS OF THE FORMER RUSSIAN EMPIRE AND TURKEY: The Republic of Northern Caucasus—Georgia and Azerbaïjan—The Bolshevists in the Republics of Caucasus and of the Transcaspian Isthmus—Armenians and Moslems - 357—369 IX. TURKEY AND THE SLAVS: Slavs versus Turks—Constantinople and Russia - 370—408 2 THE TURKS AND EUROPE I THE TURKS The peoples who speak the various Turkish dialects and who bear the generic name of Turcomans, or Turco-Tatars, are distributed over huge territories occupying nearly half of Asia and an important part of Eastern Europe. -

XIX. Yüzyılda Piyano Ve Osmanlı Kadını*

Araştırma Makalesi https://doi.org/10.46868/atdd.77 Original Article XIX. Yüzyılda Piyano ve Osmanlı Kadını* Arif Güzel* ORCID: 0000-0002-0144-1145 Öz XIX. Yüzyıl Osmanlı Devleti’nin idari ve sosyal alanda büyük değişimlere uğradığı bir çağdır. Devletin yapısal değişiminin yanında sosyal alanda da birçok değişim gözlenir. Bu sosyal değişimlerden biriside müzikal dönüşümdür. Batı müziğinin Osmanlı topraklarında kabul görmesiyle birlikte bu müziğin en mühim sazı (enstrümanı) olan piyano hem Osmanlı Sarayı’nda hem de “Osmanlı kentlisi” arasında Avrupai görünümün ve müzikal estetiğin simgesi olarak yaygınlaşır. Bu değişim rüzgârları Osmanlı kadınını da içine alır. Kadın sultanlar, devlet adamlarının kızları ve hâli vakti yerinde olan aileler özel hocalar aracılığıyla piyano eğitimi almaya başlarlar. Müzikal dönüşüm, kadınların sosyal hayata katılımlarını kolaylaştıracak bir basamak olur. Yetenekli Osmanlı kadını piyano icra etmekteki maharetini gösterir. Gerek saray gerekse toplum içerisinden fevkalade kadın piyano icracıları ve besteciler çıkar. Bu çalışmada Osmanlı müzikal dönüşüm süreci piyano ve piyano icracısı Osmanlı kadınları üzerinden değerlendirilerek sosyal dönüşümün açıklanması amaçlanmıştır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Osmanlı Devleti, Piyano, Müzik, Kadın Gönderme Tarihi: 16/11/2020 Kabul Tarihi:20/03/2021 * Bu makale yazarın ‘’XIX. Yüzyılda Sultanın Mülk ünde Piyano’’, adlı yüksek lisans tezinden üretilmiştir. *Doktora Öğrencisi, Balıkesir Üniversitesi, Tarih Anabilim Dalı, Tarih Bölümü, Balıkesir- Türkiye, [email protected] Bu makaleyi şu şekilde kaynak gösterebilirsiniz: GÜZEL, A., ‘’XIX. Yüzyılda Piyano ve Osmanlı Kadını’’, Akademik Tarih ve Düşünce Dergisi, C. 8, S. 1, 2021, s.246-261. Akademik Tarih ve Düşünce Dergisi Cilt:8 / Sayı:1 Güzel/ ss 246-261 Mart 2020 Piano and Ottoman Women In The XIX. Centruy Arif Güzel* ORCID: 0000-0002-0144-1145 Abstract The XIX. -

Sabiha Gökçen's 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO ―Sabiha Gökçen‘s 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation Formation and the Ottoman Armenians A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Fatma Ulgen Committee in charge: Professor Robert Horwitz, Chair Professor Ivan Evans Professor Gary Fields Professor Daniel Hallin Professor Hasan Kayalı Copyright Fatma Ulgen, 2010 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Fatma Ulgen is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION For my mother and father, without whom there would be no life, no love, no light, and for Hrant Dink (15 September 1954 - 19 January 2007 iv EPIGRAPH ―In the summertime, we would go on the roof…Sit there and look at the stars…You could reach the stars there…Over here, you can‘t.‖ Haydanus Peterson, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, reminiscing about the old country [Moush, Turkey] in Fresno, California 72 years later. Courtesy of the Zoryan Institute Oral History Archive v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………….... -

Tiyatro : Hürrem Sultan – Aşk Hastası

G Ü N D E M Tiyatro Hürrem Sultan Son aylarda TRT’de ve başka bir özel kanalda harem hayatının iç Osmanlı tarihinde içinde kendi- yüzünü göstermeye çalışan iki dizi sine yurt içinde ve yurt dışındaki dolayısıyla yazılı ve görsel basında çalışmalarda özel bir yer ayrılan birçok haber, eleştiri ve yorum Kanuni Sultan Süleyman, 1512- yayınlarına tanık olduk. Ancak aynı 1566 yılları arasında hüküm sürerken tarihlerde Devlet Tiyatrosunda sah- hasekisi Hürrem (1500-1558) ile nelenen Hürrem Sultan hakkında gaze- nikah kıydırmış ve bu davranışıyla telerde ve dergilerde hemen hemen kendisinden bir hayli söz ettirmiştir. hiçbir yazar -sanat eleştirmeni de dâhil Hürrem Sultan nikâh kıyılmasından olmak üzere- kalem oynatmadı. Oysa sonra, sarayın hemen hemen bütün iç işlerinde önemli bir rol oynamıştır. bu Hürrem Sultan piyesi gerçekten Bütün kaynaklarda Slav kökenli görülmeye değer, güzel bir sanat eseri olduğu belirtilen Hürrem’in Lehistan idi. topraklarında esir edilen- Bir tıp doktoru olan ler arasında en talihli kişi Orhan Asena (7.1.1922- olduğu kesindir. Çünkü 15.2.2001) bu eseri çok Osmanlı Devleti'nde ilk önceleri, 1960 yılında kez bir cariye iken köle- yazmıştı. Aradan elli yıldan likten kurtulan, hür ve fazla geçmiş olmasına nikâh kıyılarak padişahın rağmen değerinden ve yegâne hanımlığına güncelliğinden bir şey mazhar olmuştur. Kendi öz kaybetmeyen bu piyes- oğullarının tahtın varisi ola- ten başka diğer eserleri de bilmesi için sarayda çeşitli sahnelenen Orhan Asena entrikalar çevirmiştir. Ayrı bu yolda çeşitli ödül- ve özel bir yönetime sahip lere da layık görülmüştü. olan harem hayatı, renkli olduğu ka- Kocaoğlan 1956’da Basın Yayın Ge- dar da bir hayli dramatik sahnelerle nel Müdürlüğünün açtığı yarışmada doludur. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

Turkish Plastic Arts

Turkish Plastic Arts by Ayla ERSOY REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM PUBLICATIONS © Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism General Directorate of Libraries and Publications 3162 Handbook Series 3 ISBN: 978-975-17-3372-6 www.kulturturizm.gov.tr e-mail: [email protected] Ersoy, Ayla Turkish plastic arts / Ayla Ersoy.- Second Ed. Ankara: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2009. 200 p.: col. ill.; 20 cm.- (Ministry of Culture and Tourism Publications; 3162.Handbook Series of General Directorate of Libraries and Publications: 3) ISBN: 978-975-17-3372-6 I. title. II. Series. 730,09561 Cover Picture Hoca Ali Rıza, İstambol voyage with boat Printed by Fersa Ofset Baskı Tesisleri Tel: 0 312 386 17 00 Fax: 0 312 386 17 04 www.fersaofset.com First Edition Print run: 3000. Printed in Ankara in 2008. Second Edition Print run: 3000. Printed in Ankara in 2009. *Ayla Ersoy is professor at Dogus University, Faculty of Fine Arts and Design. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 Sources of Turkish Plastic Arts 5 Westernization Efforts 10 Sultans’ Interest in Arts in the Westernization Period 14 I ART OF PAINTING 18 The Primitives 18 Painters with Military Background 20 Ottoman Art Milieu in the Beginning of the 20th Century. 31 1914 Generation 37 Galatasaray Exhibitions 42 Şişli Atelier 43 The First Decade of the Republic 44 Independent Painters and Sculptors Association 48 The Group “D” 59 The Newcomers Group 74 The Tens Group 79 Towards Abstract Art 88 Calligraphy-Originated Painters 90 Artists of Geometrical Non-Figurative