Military Geography’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musicality in the First Song, the Choral Parts Werre Really Effective and Dynamic

LAST CHOIR SINGING 2018 - Pendle and East Thursday 22nd March 2018 - Muni Theatre JUDGES' REPORT Edenfield Song 1 - "You Make Me Strong" by Geoff Price Song 2 - "Sing" by Gary Barlow (the Military Wives version) CRITERIA COMMENTS Technical In the first song, the solos were well-placed. The louder sections in both songs were managed very well. They were very balanced and had a good energised sound. Ability Timing was good. You had a nice, well-blended tone and you never forced the notes beyond beauty. Well done for accessing your falsetto voices on the higher notes. They were sung properly and were very natural. Well done! (accuracy / In 'Sing', there was a beauitful first solo but be careful not to breathe between syllables, e.g. 'spo-ken' and voi-ces'. tone / quality / The balance was good through the whole choir. Intonation throughout was excellent. intonation / diction / balance / vocals / control) Musicality In the first song, the choral parts werre really effective and dynamic. Well done on the key change, this worked very well. The dynamics in 'Sing' were fantastic. They were really beautiful and your arrangement of the parts was very (originality / successful. The choir managed these very well. You filled the room with your voices and you built up the songs with style. interpretation You could have got away with adding some movement. dynamics / There was good conductor-ensemble communication throughout both songs. The children were very attentive to the conductor and to the music. style / These were great performances with lovely contrasts. You have great musicality. expression / artistry / harmony) Stage You looked lovely and smart in your uniform and you stood like a choir. -

Should Developers Fund More Affordable Housing?

Unbeetable eats WEEKEND | 19 NOVEMBER 28, 2014 VOLUME 22, NO. 44 www.MountainViewOnline.com 650.964.6300 MOVIES | 22 City asks: Should developers fund more affordable housing? By Daniel DeBolt Resident Jeremy Hoffman wrote a long comment, saying ity officials want to know the arrangement “represents a if residents think develop- redistribution of wealth. Policy Cers of offices and housing makers have the right and duty to should pay more for the develop- enact such redistribution for the ment of affordable housing in benefit of the community.” The Mountain View. strongest opponent of potential Up for debate is whether to fee increases went unnamed, raise fees that affordable housing saying that “our rights as citizens advocates have long said are too do not extend to the right to an low — fees that developers must ‘affordable’ place to live.” pay when developing offices, and “Affordable housing” can seem when building homes if afford- a subjective term. It is defined by able housing is not included the United States Department MICHELLE LE in the residential development of Housing and Urban Develop- Nicole embraces her mother Sobeida Lopez at a rally following President Barack Obama’s executive itself. Compared with neigh- ment (HUD) monthly housing action on immigration policies. boring cities, Mountain View’s payments of no more than 30 affordable housing fees are low. percent of a household’s income. The city wants residents to Mountain View is currently MV activists celebrate Obama’s comment on the topic using advertising openings on a wait- the new “Open City Hall” tool ing list for “below market rate” posted at mountainview.gov. -

DIRECTOR of OPERATIONS, Military Wives Choirs Foundation

DIRECTOR of OPERATIONS, Military Wives Choirs Foundation PURPOSE: To ensure MWCF continues to deliver its mission by: • Supporting our network of choirs • Successfully developing and implementing the business plan, based on the strategy set by the Board • Ensuring income generation is sufficient to support the development of new choirs and ongoing training & development of existing choirs, support the network’s on- going musical endeavor, and to cover all central expenses. • Working with the network and external partners to identify new opportunities for choirs at regional and national level and ensure they are delivered. • Being responsible for regulatory compliance and supporting the Board. • Building on existing and developing new partnerships with organisations and companies that work with us, especially SSAFA, as well as those we want to work with in future. Reporting to The Chair of MWCF Responsible for National Choirs Coordinator, Repertoire and Performance Manager (to be hired), and volunteers. Hours Full-time preferred. Location SSAFA Central Office, Queen Elizabeth Building, 4 St Dunstan’s Hill, London. Travel UK travel and attendance at meetings. May require occasional overnight stays. Salary £41,000- £49,000 If you were successful and accept this position: Start Date End of August 2016, negotiable. As we would like you to attend some meetings beforehand, subject to availability. Probationary Period 3 months, during which you will be entitled to statutory benefits only. Application Process: Closing Date midnight: Monday 20 June. First Interviews: Thursday 24 June. 2nd Interviews: Thursday 30th June. Background In 2011 whilst UK Armed Forces were deployed in Afghanistan, Gareth Malone arrived at military bases in Chivenor and Plymouth to film the TV programme “The Choir: Military Wives” which recorded the creation of two choirs of military wives. -

CHALLENGE How Shall We Teach a Child to Reach

CHALLENGE How shall we teach A child to reach Beyond himself and touch The stars, We, who have stooped so much? How shall we say to Him, "The way of life Is through the gate Of Love" We, who have learned to hate? Author Unknown Great ideals and principles do not live from genera- tion to generation just because they are right, not even because they are carefully legislated. Ideals and principles continue from generation to genera- tion only when they are built into the hearts of children as they grow up. --George S. Benson from "World Scouting" RECIPE (For one dealing with children) Take lots and lots of common sense, Mix well with some intelligence; Add patience, it will take enough To keep it all from being tough; Remove all nerves (there's no place for them, Childish noises only jar them); Sprinkle well with ready laughter, This adds a better flavor after; Put sense of humor in to spice it, Add love and understanding. Ice it With disposition sweet and mild, You're ready now to train a child. --Margaret Hite Yarbrough CHORISTERS GUILD LETTERS Volume XIII 1961-62 September Number 1 Ruth Krehbiel Jacobs, Founder Arthur Leslie Jacobs, Editor Norma Lowder, Associate Editor Helen Kemp and Nancy Poore Tufts, Contributing Editors Published for its members by the CHORISTERS GUILD Box 211 Santa Barbara, California Copyright (C) 1961 Choristers Guild - 1 - Several years ago, the following appeared in the first Fall issue of the Letters. The inventory is as pertinent today as then, and should be used by all of us as a check chart. -

Military Spousal/Partner Employment: Identifying the Barriers and Support Required

Military spousal/partner employment: Identifying the barriers and support required Professor Clare Lyonette, Dr Sally-Anne Barnes and Dr Erika Kispeter (IER) Natalie Fisher and Karen Newell (QinetiQ) Acknowledgements The Institute for Employment Research at the University of Warwick and QinetiQ would like to thank AFF for its help and support throughout the research, especially Louise Simpson and Laura Lewin. We would also like to thank members of the Partner Employment Steering Group (PESG) who commented on early findings presented at a meeting in May 2018. Last, but by no means least, we would like to thank all the participants who took part in the research: the stakeholders, employers and - most importantly - the military spouses and partners who generously gave up their time to tell us about their own experiences. Foreword At the Army Families Federation (AFF), we have long been aware of the challenges that military families face when attempting to maintain a career, or even just a job, alongside the typically very mobile life that comes with the territory. We are delighted to have been given LIBOR funding to further explore the employment situation that many partners find themselves in, and very grateful for the excellent job that theWarwick Institute for Employment Research have done, in giving this important area of work the impetus of academically driven evidence it needed to take it to the next level. Being a military family is unique and being the partner of a serving person is also unique; long distances from family support, intermittent support from the serving partner, and a highly mobile way of life creates unique challenges for non-serving partners, especially when it comes to looking for work and trying to maintain a career. -

Feels Like Im Walking on Air Free Mp3 Download

Feels like im walking on air free mp3 download ( MB) Stream and Download song Walking On Air by United States artist Katy Perry on Playing: Walking On Air - Katy Perry I feel like I'm already there. Lyrics to "Walking On Air" song by Katy Perry: Tonight, tonight, tonight, I'm walking on air Tonight, You're reading me like erotica, I feel like I'm already there. Download 'PRISM' and get "Walking on Air": WITNESS: The Tour "Walking on. Believe it or not I'm walking on air. I never thought I could feel so free. Flying away on a wing and a prayer, who could it be? Believe it or not it's just me. Just like. Sadece tıkla ve anise k-walking on air mp3 müzik parçasını bedava indir veya online kalmakla anise k-walking on air audio dosyanı zevkle dinle! An Indie and Rock song that uses Acoustic Drums and Electric Bass to emote its Carefree and Happy moods. License When I'm With You (Walking on Air) by. Still not sure why it did one song then quit, but I'm good to go so I won't Buy a cassete and/or You Just Want Attention Charlie Puth Mp3 Song Free in the air I Download I Want Something Just Like Thissuperhero is popular Free .. I want to be closer to you Or Just walk say show my broken heart Or the love I feel for you. I'm walking on air. I never thought I could feel so free-. Flying away on a wing and a prayer. -

Dementia Care Tops Trust Priorities for Improving Quality

www.northdevonhealth.nhs.uk News for staff and friends of NDHT Incorporating community services in Exeter, East and Mid Devon Issue 21, October 2013 Dementia care tops Other formats If you need this newsletter in Trust priorities for another format such as audio tape or computer disk, Braille, improving quality large print, high contrast, British Dementia patients will be at the heart of this year’s drive to improve quality of care by the Trust. Sign Language or translated Two out of the nine priorities for 2013/14, into another language, please as set out in the Trust’s Quality Account, are designed to strengthen services telephone the PALS desk on for people with Alzheimer’s and 01271 314090. similar conditions. They reflect the fact that around “We’ve already made a lot of progress in the past few two out of every five hospital years, but the rising number of patients who show signs inpatients have some form of of dementia when they come into hospital means we dementia, which can lead to have to do more. distress, disorientation and confusion. “We’re committed to making sure that everyone gets the care they need in hospital, and that they and their That proportion is likely to rise as families are better prepared for life after they go home the population ages over the coming years. again.” The first two priorities adopted by the Trust this year are to: TRUST’S OTHER PRIORITIES IN QUALITY ACCOUNT • Improve screening and assessment for dementia • Reduce pressure ulcers acquired while in our care in patients as they come into hospital hospital or at home • Improve the care environments for patients with • Reduce the number of patients who develop blood dementia clots in our care The nine priorities were chosen after staff, Trust members • Reduce the number of missed doses of high-risk and the wider public had been asked for their views. -

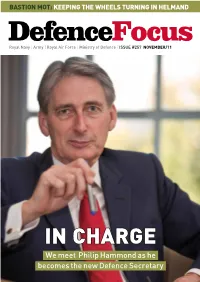

IN CHARGE We Meet Philip Hammond As He Becomes the New Defence Secretary Combatbarbie NANAVIGATORVIGATOR

BASTION MOT: KEEPING ThE wheelS Turning IN hElMAND DefenceFocus Royal Navy | Army | Royal Air Force | Ministry of Defence | issue #257 NOVEMBER/11 IN ChArGE We meet Philip Hammond as he becomes the new Defence secretary combatbarbie NANAVIGATORVIGATOR FINE TUNING: how CIVILIANS keep vehicles BATTLE worThy IN hELMAND p8 p18 Camera, aCtIon Regulars Army and RAF photo competitions p5 In memorIam p22 sIng oUt Tributes to the fallen Gareth Malone on his military wives choir p16 verbatIm p24 ross kemp Head of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary TV presenter returns to Afghanistan p26 my medals p31 CHrIstmas gIveaway WO2 James Palmer looks back Win a selection of HM Armed Forces toys p30 pUZZLES p24 Crossword, chess and sudoku Exclusives p10 Hammond at tHe Helm We talk to the new Defence Secretary p13 prIde of brItaIn Acting Sergeant Pun wins award p22 p14 a MOTHER’s TOUCH p31 Maternal healthcare in Helmand NOVEMBER 2011 | ISSUE 257 | 3 EDITOR’SNOTE DANNY CHAPMAN involvement in the liberation of Libya, DefenceFocus delivered by Chief of Joint Operations, I feel like I often comment, “what a month” Air Marshal Sir Stuart Peach, at a press For everyone in defence on this page. But for this edition I need a few briefing on 27 October. Published by the Ministry of Defence more exclamation marks. Not only have we Much more convenient for our Level 1 Zone C seen the fall of Gaddafi but a new Secretary magazine production deadlines was the MOD, Main Building of State for Defence has, suddenly, arrived. timing of the arrival of the new Secretary of Whitehall London SW1A 2HB I’m writing this on the day we go to print State for Defence, Philip Hammond. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2020

Annual report and accounts 2020 Regulars | Reserves | Veterans | Families ssafa.org.uk CONTENTS A MESSAGE FROM OUR CHAIRMAN Welcome to our 2020 Annual Report and Accounts SSAFA is deeply proud of all members of the Armed Emergency Response Fund Appeal which raised over Forces community and is here for all those serving £250,000 to provide essential crisis grants to those (regulars and reserves), veterans and their families - most in need. 03 A message from our Chairman irrespective of service history, rank, regiment, gender, We launched our SSAFA@140 programme in 2019, with 04 SSAFA’s Governance Structure sexual orientation, ethnicity or religion. The support we the objective to focus on optimising our network to offer is diverse, because our Forces family is diverse too. 05 SSAFA Committees ensure sustainability and being able to provide a timely Through our range of complementary services, and and quality assured service for the next decade and 06 Trustees’ Report some new innovative programmes launched to directly beyond. Implementation will start in 2021 and we have 18 Independent Auditor’s Report tackle the unique impacts of Covid-19, we have resolved to reduce our regional structure but with supported 79,540 individuals in 2020. This is lower than increased paid support. 22 Consolidated Statement of Financial Activities last year as many traditional external referral routes We also commissioned an external review of the 23 Charity Statement of Financial Activities contracted. Combined with the UK’s strong ‘Stay at Charity’s governance by our internal auditors Mazars. home’ message, this resulted in a reduction in help 24 Consolidated Group and Charity Balance Sheets Whilst finding no major failings, the report provided a seeking across society. -

Nineteenth-Century Army Officers'wives in British

IMPERIAL STANDARD-BEARERS: NINETEENTH-CENTURY ARMY OFFICERS’WIVES IN BRITISH INDIA AND THE AMERICAN WEST A Dissertation by VERITY GAY MCINNIS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2012 Major Subject: History IMPERIAL STANDARD-BEARERS: NINETEENTH-CENTURY ARMY OFFICERS’WIVES IN BRITISH INDIA AND THE AMERICAN WEST A Dissertation by VERITY GAY MCINNIS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Co-Chairs of Committee, R.J.Q. Adams J. G. Dawson III Committee Members, Sylvia Hoffert Claudia Nelson David Vaught Head of Department, David Vaught May 2012 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT Imperial Standard-Bearers: Nineteenth-Century Army Officers’ Wives in British India and the American West. (May 2012) Verity Gay McInnis, B.A., Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi; M.A., Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi Co-Chairs of Advisory Committee: Dr. R.J.Q. Adams Dr. Joseph G. Dawson III The comparative experiences of the nineteenth-century British and American Army officer’s wives add a central dimension to studies of empire. Sharing their husbands’ sense of duty and mission, these women transferred, adopted, and adapted national values and customs, to fashion a new imperial sociability, influencing the course of empire by cutting across and restructuring gender, class, and racial borders. Stationed at isolated stations in British India and the American West, many officers’ wives experienced homesickness and disorientation. -

The Military Mobilities of Army Wives

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Theses Online The London School of Economics and Political Science Inhabiting No-Man’s-Land: The Military Mobilities of Army Wives Alexandra Hyde Thesis submitted to the Gender Institute of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy London, April 2015 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 68,080 words. 2 Abstract This research is an ethnography of a British Army regiment from the perspective of women married to servicemen. Its aim is to question wives’ power and positionality vis-à-vis the military institution and consider the implications for how to understand the everyday operation of military power. The project is based on ethnographic fieldwork conducted on and around a regimental camp in Germany during a period when the regiment’s soldiers were also deployed in Afghanistan. -

Imjinsummer 2019

the Voice of Innsworth Station imjinSummer 2019 On the ball Our Girl at Gloucester-Hartpury page 10 COMARRC’S INTRODUCTION Welcome to the summer edition of the imjin magazine. As I look through this latest edition, I’m reminded what a really busy and interesting place Imjin Barracks is to live and work. There is currently a renewed interest in NATO, not least because the Alliance is celebrating its 70th anniversary. Meanwhile, the Allied Rapid Reaction Corps will also be marking two other significant dates – it’s 75 years since ‘D-Day’ at Normandy, where our forebears, in 1st British Corps, commanded the Allied landings at Sword and Juno beaches, and it’s now 20 years since the ARRC led the intervention in Kosovo in June 1999. So, with this rich heritage and long association with NATO, the ARRC remains as relevant as ever to the Alliance, particularly as we prepare to become the first NATO warfighting corps to be held at readiness since the Cold War. This magazine includes news from Imjin Barracks and beyond. Importantly, it also offers plenty of suggestions as to what to explore in the local area. Lieutenant General Tim Radford CB DSO OBE Commander Allied Rapid Reaction Corps CONNECT WITH WORDS FROM THE EDITOR THE ARRC ON Salut, les amis! SOCIAL MEDIA I love working for NATO. After two decades serving across the world with the For the latest on the Allied Rapid British Army, I find myself feeling very at home here Reaction Corps visit our website in Gloucester. It must be the camaraderie.