Falklands Royal Navy Wives: Fulfilling a Militarised Stereotype Or Articulating Individuality?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Radares 909 Durante La Guerra De Malvinas

BCN 832 9 El Capitán de Navío (R) Néstor Antonio Domínguez egresó de la ENM en 1956 (Promoción 83) y pasó a retiro voluntario en 1983. Estudió Ingeniería Electromecánica (orientación Electrónica) en la Facultad de Ingeniería de la UBA y posee el título de Ingeniero de la Armada. Es estudiante avanzado de la Carre- ra de Filosofía de dicha Universidad. LOS RADARES 909 DURANTE Fue Asesor del Estado Mayor General de la Armada en Materia LA GUERRA DE MALVINAS Satelital; Consejero Especial en Ciencia y Tecnología y Coordinador HMS Sheffield. Académico en Cursos de Capaci- IMAGEN: WWW.BASENAVAL.COM Néstor A. Domínguez tación Universitaria, en Intereses Marítimos y Derecho del Mar y Marítimo, del Centro de Estudios Es- tratégicos de la Armada; y profesor, Postulado de Horner: “La experiencia aumenta directamente investigador y tutor de proyectos de investigación en la Maestría en según la maquinaria destrozada”. Defensa Nacional de la Escuela de Defensa Nacional. Es Académico Fundador y Presi- “La tecnología está dominada por dos tipos de personas: dente de la Academia del Mar y miembro del Grupo de Estudios de • Aquellos que entienden lo que no manejan. Sistemas Integrados en la USAL. • Aquellos que manejan lo que no entienden”. Ha sido miembro de las Comisiones para la Redacción de los Pliegos y De las Leyes de Murphy. (1) la Adjudicación para el concurso in- ternacional por el Sistema Satelital Nacional de Telecomunicaciones por omo lo he expresado en un artículo anterior referido a esta Satélite Nahuel y para la redacción historia (Boletín Nº830), al regreso al país con el destructor inicial del Plan Espacial Nacional. -

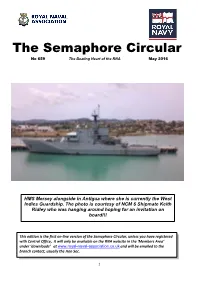

The Semaphore Circular No 659 the Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 659 The Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016 HMS Mersey alongside in Antigua where she is currently the West Indies Guardship. The photo is courtesy of NCM 6 Shipmate Keith Ridley who was hanging around hoping for an invitation on board!!! This edition is the first on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. April Open Day 2. New Insurance Credits 3. Blonde Joke 4. Service Deferred Pensions 5. Guess Where? 6. Donations 7. HMS Raleigh Open Day 8. Finance Corner 9. RN VC Series – T/Lt Thomas Wilkinson 10. Golf Joke 11. Book Review 12. Operation Neptune – Book Review 13. Aussie Trucker and Emu Joke 14. Legion D’Honneur 15. Covenant Fund 16. Coleman/Ansvar Insurance 17. RNPLS and Yard M/Sweepers 18. Ton Class Association Film 19. What’s the difference Joke 20. Naval Interest Groups Escorted Tours 21. RNRMC Donation 22. B of J - Paterdale 23. Smallie Joke 24. Supporting Seafarers Day Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General -

Imperial Nostalgia: Victorian Values, History and Teenage Fiction in Britain

RONALD PAUL Imperial Nostalgia: Victorian Values, History and Teenage Fiction in Britain In his pamphlet, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, on the seizure of French government power in 1851 by Napoleon’s grandson, Louis, Karl Marx makes the following famous comment about the way in which political leaders often dress up their own ideological motives and actions in the guise of the past in order to give them greater historical legitimacy: The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living. And just when they seem engaged in revolutionizing themselves and things, in creating something that has never yet existed, precisely in such periods of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service and borrow from them names, bat- tle-cries, and costumes in order to present the new scene of world history in this time-honoured disguise and this borrowed language.1 One historically contentious term that has been recycled in recent years in the public debate in Britain is that of “Victorian values”. For most of the 20th century, the word “Victorian” was associated with negative connotations of hypercritical morality, brutal industrial exploitation and colonial oppression. However, it was Mrs Thatcher who first gave the word a more positive political spin in the 1980s with her unabashed celebration of Victorian laissez-faire capitalism and patriotic fervour. This piece of historical obfuscation was aimed at disguising the grim reality of her neoliberal policies of economic privatisation, anti-trade union legislation, cut backs in the so-called “Nanny” Welfare State and the gunboat diplomacy of the Falklands War. -

The Falklands/Malvinas Conflict by Jorge O

Lessons from Failure: The Falklands/Malvinas Conflict by Jorge O. Laucirica The dispute between Argentina and Great Britain over the Falkland/Malvinas Islands1 led to the only major war between two Western countries since World War II. It is an interesting case for the study of preventive diplomacy and conflict management, as it involves a cross-section of international relations. The conflict involved (a) a major power, Great Britain; (b) an active U.S. role, first as a mediator and then as an ally to one of the parties; (c) a subcontinental power, albeit a “minor” player in a broader context, Argentina; (d) a global intergovernmental organization, the United Nations; and (e) a regional intergovernmental organization, the Organization of American States (OAS). The Falklands/Malvinas territory encompasses two large islands, East and West Falkland—or Soledad and Gran Malvina, according to the Argentine denomination— as well as some 200 smaller islands, all of them scattered in a 7,500-mile area situated about 500 miles northeast of Cape Horn and 300 miles east of the Argentine coast- line. The population of the Falklands is 2,221, according to the territorial census of 1996.2 Argentina formally brought the dispute over sovereignty to the attention of the UN, in the context of decolonization, in 1965. A process including resolutions, griev- ances, and bilateral negotiations carried on for seventeen years, culminating in the 1982 South Atlantic war. Eighteen years after the confrontation, and despite the lat- est changes in the status quo (commercial flights between the islands and Argentina were reestablished in 1999), the conflict remains open, with Argentina still clinging to its claims of sovereignty over Malvinas and the South Georgia, South Orcadas, South Shetland, and South Sandwich Islands, all of them located in the South Atlan- tic and administered by the United Kingdom. -

198J. M. Thornton Phd.Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Thornton, Joanna Margaret (2015) Government Media Policy during the Falklands War. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/50411/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Government Media Policy during the Falklands War A thesis presented by Joanna Margaret Thornton to the School of History, University of Kent In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History University of Kent Canterbury, Kent January 2015 ©Joanna Thornton All rights reserved 2015 Abstract This study addresses Government media policy throughout the Falklands War of 1982. It considers the effectiveness, and charts the development of, Falklands-related public relations’ policy by departments including, but not limited to, the Ministry of Defence (MoD). -

Materializing the Military

MATERIALIZING THE MILITARY Edited by Bernard Finn Barton C Hacker Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC Associate Editors Robert Bud Science Museum, London Helmuth Trischler Deutsches Museum, Munich . sCience museum Published 2005 by NMSI Trading Ltd, Science Museum, Exhibition Road, London SW7 2DD All rights reserved © 2005 Board ofTrustees of the Science Museum, except for contributions from employees of US national museums Designed by Jerry Fowler Printed in England by the Cromwell Press ISBN 1 90074760 X ISSN 1029-3353 Website http://www.nmsi.ac.uk Artefacts series: studies in the history of science and technology In growing numbers, historians are using technological artefacts in the study and interpretation of the recent past. Their work is still largely pioneering, as they investigate approaches and modes of presentation. But the consequences are already richly rewarding. To encourage this enterprise, three of the world's greatest repositories of the material heritage of science and technology: the Deutsches Museum, the Science Museum and the Smithsonian Institution, are collaborating on this book series. Each volume treats a particular subject area, using objects to explore a wide range of issues related to science, technology and medicine and their place in society. Edited by Robert Bud, Science Museum, London Bernard Finn, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC Helmuth Trischler, Deutsches Museum, Munich Volume 1 Manifesting Medicine Principal Editor Robert Bud Volume 2 Exposing Electronics Principal Editor Bernard Finn Volume 3 Tackling Transport Principal Editors Helmuth Trischler and Stefan Zeilinger Volume 4 Presenting Pictures Principal Editor Bernard Finn Volume 5 Materializing the Military Principal Editors Bernard Finn and Barton C Hacker Volume. -

Issue 432 April/May 2020

NUMBER APRIL / MAY 432 ! 2020 2210 (Cowley) SQN AIR CADET NEWS: The start of 2020 has seen cadets and staff from 2210 (Cowley) Sqn involved in a number of exciting activities! They attended Thames Valley Wing’s first Multi-Activity Course: it was accommodated on HMS Bristol, a Type 82 destroyer which saw action in the Falklands, and is berthed in Portsmouth. Cadets could choose from courses in leadership, first aid, radio communications, instructional techniques or weapon handling. Cadets from 2210 (Cowley) Sqn also joined others from across Oxfordshire & Berkshire to practise their marksmanship skills by firing the L144A1 target rifle: they were trained to use the weapon safely, then coached during firing to ensure they could accurately & consistently hit a target 25 metres away. Finally 2210 (Cowley) Sqn undertook a 12 Km walk in the countryside to put into practice map reading and navigation skills learnt on normal parade nights. Cadets took it in turn to lead the group, and decide on the route & direction. If you are aged 12 (& in Yr 8) to 19 and interested in joining as a cadet or as a member of staff, please feel free to attend (Mondays & Wednesdays 7.15-9.30 pm, Sandy Lane West) or contact Fg Off O'Riordan on [email protected]. Fg Off Tim O’Riordan (photos © T O’R: all permissions received) THE SCHOOL READINESS PROJECT: GROWING MINDS NEWS FROM LITTLEMORE PLAYGROUP This is a partnership between John Henry Newman Academy, Thank you to the Parish Council for the 2nd part of their grant. Peeple www.peeple.org.uk, Home-Start www.home-start.org.uk, & the We’ve used it to buy much-needed resources: these include Imagination Library imaginationlibrary.com/uk). -

Musicality in the First Song, the Choral Parts Werre Really Effective and Dynamic

LAST CHOIR SINGING 2018 - Pendle and East Thursday 22nd March 2018 - Muni Theatre JUDGES' REPORT Edenfield Song 1 - "You Make Me Strong" by Geoff Price Song 2 - "Sing" by Gary Barlow (the Military Wives version) CRITERIA COMMENTS Technical In the first song, the solos were well-placed. The louder sections in both songs were managed very well. They were very balanced and had a good energised sound. Ability Timing was good. You had a nice, well-blended tone and you never forced the notes beyond beauty. Well done for accessing your falsetto voices on the higher notes. They were sung properly and were very natural. Well done! (accuracy / In 'Sing', there was a beauitful first solo but be careful not to breathe between syllables, e.g. 'spo-ken' and voi-ces'. tone / quality / The balance was good through the whole choir. Intonation throughout was excellent. intonation / diction / balance / vocals / control) Musicality In the first song, the choral parts werre really effective and dynamic. Well done on the key change, this worked very well. The dynamics in 'Sing' were fantastic. They were really beautiful and your arrangement of the parts was very (originality / successful. The choir managed these very well. You filled the room with your voices and you built up the songs with style. interpretation You could have got away with adding some movement. dynamics / There was good conductor-ensemble communication throughout both songs. The children were very attentive to the conductor and to the music. style / These were great performances with lovely contrasts. You have great musicality. expression / artistry / harmony) Stage You looked lovely and smart in your uniform and you stood like a choir. -

DIRECTOR of OPERATIONS, Military Wives Choirs Foundation

DIRECTOR of OPERATIONS, Military Wives Choirs Foundation PURPOSE: To ensure MWCF continues to deliver its mission by: • Supporting our network of choirs • Successfully developing and implementing the business plan, based on the strategy set by the Board • Ensuring income generation is sufficient to support the development of new choirs and ongoing training & development of existing choirs, support the network’s on- going musical endeavor, and to cover all central expenses. • Working with the network and external partners to identify new opportunities for choirs at regional and national level and ensure they are delivered. • Being responsible for regulatory compliance and supporting the Board. • Building on existing and developing new partnerships with organisations and companies that work with us, especially SSAFA, as well as those we want to work with in future. Reporting to The Chair of MWCF Responsible for National Choirs Coordinator, Repertoire and Performance Manager (to be hired), and volunteers. Hours Full-time preferred. Location SSAFA Central Office, Queen Elizabeth Building, 4 St Dunstan’s Hill, London. Travel UK travel and attendance at meetings. May require occasional overnight stays. Salary £41,000- £49,000 If you were successful and accept this position: Start Date End of August 2016, negotiable. As we would like you to attend some meetings beforehand, subject to availability. Probationary Period 3 months, during which you will be entitled to statutory benefits only. Application Process: Closing Date midnight: Monday 20 June. First Interviews: Thursday 24 June. 2nd Interviews: Thursday 30th June. Background In 2011 whilst UK Armed Forces were deployed in Afghanistan, Gareth Malone arrived at military bases in Chivenor and Plymouth to film the TV programme “The Choir: Military Wives” which recorded the creation of two choirs of military wives. -

Adobe PDF File

BOOK REVIEWS Lewis R. Fischer, Harald Hamre, Poul that by Nicholas Rodger on "Shipboard Life Holm, Jaap R. Bruijn (eds.). The North Sea: in the Georgian Navy," has very little to do Twelve Essays on Social History of Maritime with the North Sea and the same remark Labour. Stavanger: Stavanger Maritime applies to Paul van Royen's essay on "Re• Museum, 1992.216 pp., illustrations, figures, cruitment Patterns of the Dutch Merchant photographs, tables. NOK 150 + postage & Marine in the Seventeenth to Nineteenth packing, cloth; ISBN 82-90054-34-3. Centuries." On the other hand, Professor Lewis Fischer's "Around the Rim: Seamens' This book comprises the papers delivered at Wages in North Sea Ports, 1863-1900," a conference held at Stavanger, Norway, in James Coull's "Seasonal Fisheries Migration: August 1989. This was the third North Sea The Case of the Migration from Scotland to conference organised by the Stavanger the East Anglian Autumn Herring Fishery" Maritime Museum. The first was held at the and four other papers dealing with different Utstein Monastery in Stavanger Fjord in aspects of fishing industries are directly June 1978, and the second in Sandbjerg related to the conferences' central themes. Castle, Denmark in October 1979. The pro• One of the most interesting of these is Joan ceedings of these meetings were published Pauli Joensen's paper on the Faroe fishery in one volume by the Norwegian University in the age of the handline smack—a study Press, Oslo, in 1985 in identical format to which describes an age of transition in the volume under review, under the title The social, economic and technical terms. -

HMS ARK ROYAL 1976-1978, the Last Commission

The ship's previous Captain, The ship's first Commanding Rear Admiral Graham. Officer, Rear Admiral D. R. F. Cambell, CB, DSC, (left) Generally they were official calls on C-in-C Fleet, but the Blue Peter programme introduced a special feature and press came too with their note books and cameras at the later in the evening, Sunset and the illumination of the Fleet ready, and the radio and local TV boys arrived with their were televised for a BBC programme `Silver Jubilee equipment of various shapes and sizes. introduced by Richard Baker. Two live television events took place from ARK Everything was now ready for the big day and we all ROYALs flight deck. On the 27th, Peter Purves of BBCs hoped for good weather. The Flypast Rehearsal as seen by several cameras. 14 FINAL REHEARSALS Monday 27 June 1 5 THE SILVER JUBILEE FLEET REVIEW 28 JUNE 1977 At last the big day arrived, and the customary poor weather At 1430 the Royal Yacht entered the Review Lines which seems to plague the Queen on big occasions was also preceded by the Trinity House vessel PATRICIA. Astern present. However we were informed that the afternoon of BRITANNIA came HMS BIRMINGHAM with wouldn't be spoilt by rain, but that it would be cold and members of the Admiralty Board and their guests, followed windy - how right they were according to those who stood by the RFA's ENGADINE, SIR GERAINT, SIR on the flight deck. TRISTRAM and LYNESS with the press and official Our families and official guests began arriving during the guests embarked. -

Military Spousal/Partner Employment: Identifying the Barriers and Support Required

Military spousal/partner employment: Identifying the barriers and support required Professor Clare Lyonette, Dr Sally-Anne Barnes and Dr Erika Kispeter (IER) Natalie Fisher and Karen Newell (QinetiQ) Acknowledgements The Institute for Employment Research at the University of Warwick and QinetiQ would like to thank AFF for its help and support throughout the research, especially Louise Simpson and Laura Lewin. We would also like to thank members of the Partner Employment Steering Group (PESG) who commented on early findings presented at a meeting in May 2018. Last, but by no means least, we would like to thank all the participants who took part in the research: the stakeholders, employers and - most importantly - the military spouses and partners who generously gave up their time to tell us about their own experiences. Foreword At the Army Families Federation (AFF), we have long been aware of the challenges that military families face when attempting to maintain a career, or even just a job, alongside the typically very mobile life that comes with the territory. We are delighted to have been given LIBOR funding to further explore the employment situation that many partners find themselves in, and very grateful for the excellent job that theWarwick Institute for Employment Research have done, in giving this important area of work the impetus of academically driven evidence it needed to take it to the next level. Being a military family is unique and being the partner of a serving person is also unique; long distances from family support, intermittent support from the serving partner, and a highly mobile way of life creates unique challenges for non-serving partners, especially when it comes to looking for work and trying to maintain a career.