Army Recruitment and Patron - Client Relationship in Colonial Punjab: a Grassroots Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders (W/Out Cnic) As of December 31, 2017

ASKARI BANK LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS (W/OUT CNIC) AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2017 S. NO. FOLIO NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDERS ADDRESSES OF THE SHAREHOLDERS NO. OF SHARES 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN C/O BANK OF AMERICA, BLUE AREA, ISLAMABAD. 2878 12 68 MR. WASEEM AHMED HOUSE NO.485, STREET NO.17, CHAKLALA SCHEME-III, RAWALPINDI. 5945 13 71 MS. SHAMEEM QUAVI SIDDIQUI 112/1, 13TH STREET, PHASE-VI, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, KARACHI-75500. 2695 14 74 MS. YAZDANI BEGUM HOUSE NO.A-75, BLOCK-13, GULSHAN-E-IQBAL, KARACHI. -

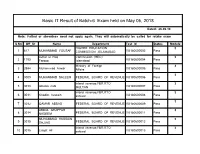

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam Held on May 05, 2018

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam S.No Off_Sr Name Department Test Id Status Module HIGHER EDUCATION 3 1 617 MUHAMMAD YOUSAF COMMISSION ,ISLAMABAD VU180600002 Pass Azhar ul Haq Commission (HEC) 3 2 1795 Farooq Islamabad VU180600004 Pass Ministry of Foreign 3 3 2994 Muhammad Anwar Affairs VU180600005 Pass 3 4 3009 MUHAMMAD SALEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600006 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 5 3010 Ghulan nabi MULTAN VU180600007 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 6 3011 Khadim hussain sahiwal VU180600008 Pass 3 7 3012 QAMAR ABBAS FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600009 Pass ABDUL GHAFFAR 3 8 3014 NADEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600011 Pass MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN 3 9 3015 SAJJAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600012 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 10 3016 Liaqat Ali sahiwal VU180600013 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 11 3017 Tariq javed sahiwal VU180600014 Pass 3 12 3018 AFTAB AHMAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600015 Pass Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Muhammad inam-ul- inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 13 3019 haq MULTAN VU180600016 Pass Ministry of Defense (Defense Division) 3 Rawalpindi. 14 4411 Asif Mehmood VU180600018 Pass 3 15 4631 Rooh ul Amin Pakistan Air Force VU180600022 Pass Finance/Income Tax 3 16 4634 Hammad Qureshi Department VU180600025 Pass Federal Board Of Revenue 3 17 4635 Arshad Ali Regional Tax-II VU180600026 Pass 3 18 4637 Muhammad Usman Federal Board Of Revenue VU180600027 -

23Rd Indian Infantry Division

21 July 2012 [23 INDIAN INFANTRY DIVISION (1943)] rd 23 Indian Infantry Division (1) st 1 Indian Infantry Brigade (2) 1st Bn. The Seaforth Highlanders (Ross-shire Buffs, The Duke of Albany’s) th th 7 Bn. 14 Punjab Regiment (3) 1st Patiala Infantry (Rajindra Sikhs), Indian State Forces st 1 Bn. The Assam Regiment (4) 37th Indian Infantry Brigade 3rd Bn. 3rd Queen Alexandra’s Own Gurkha Rifles 3rd Bn. 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles (Frontier Force) 3rd Bn. 10th Gurkha Rifles 49th Indian Infantry Brigade 4th Bn. 5th Mahratta Light Infantry 5th (Napiers) Bn. 6th Rajputana Rifles nd th 2 (Berar) Bn. 19 Hyderabad Regiment (5) Divisional Troops The Shere Regiment (6) The Kali Badahur Regiment (6) th 158 Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (7) 3rd Indian Field Regiment, Indian Artillery 28th Indian Mountain Regiment, Indian Artillery nd 2 Indian Anti-Tank Regiment, Indian Artillery (8) 68th Field Company, King George V’s Own Bengal Sappers and Miners 71st Field Company, King George V’s Own Bengal Sappers and Miners 91st Field Company, Royal Bombay Sappers and Miners 323rd Field Park Company, Queen Victoria’s Own Madras Sappers and Miners 23rd Indian Divisional Signals, Indian Signal Corps 24th Indian Field Ambulance, Indian Army Medical Corps 47th Indian Field Ambulance, Indian Army Medical Corps 49th Indian Field Ambulance, Indian Army Medical Corps © www.britishmilitaryhistory.co.uk Page 1 21 July 2012 [23 INDIAN INFANTRY DIVISION (1943)] NOTES: 1. The division was formed on 1st January 1942 at Jhansi in India. In March, the embryo formation moved to Ranchi where the majority of the units joined it. -

Pakistan's Army

Pakistan’s Army: New Chief, traditional institutional interests Introduction A year after speculation about the names of those in the race for selection as the new Army Chief of Pakistan began, General Qamar Bajwa eventually took charge as Pakistan's 16th Chief of Army Staff on 29th of November 2016, succeeding General Raheel Sharif. Ordinarily, such appointments in the defence services of countries do not generate much attention, but the opposite holds true for Pakistan. Why this is so is evident from the popular aphorism, "while every country has an army, the Pakistani Army has a country". In Pakistan, the army has a history of overshadowing political landscape - the democratically elected civilian government in reality has very limited authority or control over critical matters of national importance such as foreign policy and security. A historical background The military in Pakistan is not merely a human resource to guard the country against the enemy but has political wallop and opinions. To know more about the power that the army enjoys in Pakistan, it is necessary to examine the times when Pakistan came into existence in 1947. In 1947, both India and Pakistan were carved out of the British Empire. India became a democracy whereas Pakistan witnessed several military rulers and still continues to suffer from a severe civil- military imbalance even after 70 years of its birth. During India’s war of Independence, the British primarily recruited people from the Northwest of undivided India which post partition became Pakistan. It is noteworthy that the majority of the people recruited in the Pakistan Army during that period were from the Punjab martial races. -

Volume II Section V - South Central Asia

Volume II Section V - South Central Asia Afghanistan ALP - Fiscal Year 2012 Department of Defense On-Going Training Course Title Qty Training Location Student's Unit US Unit - US Qty Total Cost ALC ALP Scholarship 4 DLIELC, LACKLAND AFB TX Ministry of Defense DLIELC, LACKLAND AFB TX $28,804 Fiscal Year 2012 On-Going Program Totals 4 $28,804 CTFP - Fiscal Year 2012 Department of Defense On-Going Training Course Title Qty Training Location Student's Unit US Unit - US Qty Total Cost ASC12-2 - Advanced Security Cooperation Course 2 Honolulu, Hawaii, United States Afghanistan Ministry of Defense APSS $0 ASC12-2 - Advanced Security Cooperation Course 2 Honolulu, Hawaii, United States N/A APSS $0 International Counter Terrorism Fellows Program 4 NATIONAL DEFENSE UNIVERSITY National Directorate of Security (NDS) NATIONAL DEFENSE UNIVERSITY $311,316 Fiscal Year 2012 On-Going Program Totals 8 $311,316 FMF - Fiscal Year 2012 Department of State On-Going Training Course Title Qty Training Location Student's Unit US Unit - US Qty Total Cost Advanced English Language INSTR Course (AELIC) 8 DLIELC, LACKLAND AFB TX Ministry of Defense DLIELC, LACKLAND AFB TX $98,604 Country Liaison OFF 8 DLIELC, LACKLAND AFB TX Ministry of Defense DLIELC, LACKLAND AFB TX $65,356 Intermediate Level EDUC 4 COMMAND & GENERAL STAFF COLLEGE Ministry of Defense COMMAND & GENERAL STAFF COLLEGE $130,584 Fiscal Year 2012 On-Going Program Totals 20 $294,544 FMS - Fiscal Year 2012 Department of State On-Going Training Course Title Qty Training Location Student's Unit US Unit - -

Balochis of Pakistan: on the Margins of History

BALOCHIS OF PAKISTAN: ON THE MARGINS OF HISTORY November 2006 First published in 2006 by The Foreign Policy Centre 23-28 Penn Street London N1 5DL www.fpc.org.uk Email: [email protected] © Foreign Policy Centre 2006 All rights reserved ISBN-13: 978-1-905833-08-5 ISBN-10: 1-905833-08-3 PREFACE The Foreign Policy Centre is keen to promote debate about some of the worlds lesser known conflicts. The situation in Balochistan is one such example. This pamphlet sets out a powerful and well argued case that the Balochi people have been let down - by the British Empire, by the founders of modern India and by successive Governments in Pakistan. It is a fascinating analysis which we hope will contribute to constructive discussion about Balochistans future. The Foreign Policy Centre Disclaimer : The views in this paper are not necessarily those of the Foreign Policy Centre. CONTENTS Baloch and Balochistan through History A Brief Prologue The Khanate of Kalat: Between Dependency and Sovereignty The Colonial Era: The British Policy of Divide et Empera Boundary Demarcation and Trifurcation of Baloch Terrain Pakistan absorbs the Khanate Partition and the Annexation of Balochistan The Indian Position Baloch Insurgencies 1948-1977 First Guerrilla Revolt The Second Revolt Third Balochi Resistance: The 1970s The State of Nationalist Politics Today Signifiers of Balochi Nationalism a) Language b) Islam c) Sardari System d) Aversion towards Punjabi and Pathan Immigration The Post-1980 Phase The Contemporary Socio-Political Scenario in Balochistan Influence of Jihad in Afghanistan Does Islam blunt Baloch nationalism? The Baloch Resistance Movement 2000-2006 The state of Baloch Insurgency Human Rights Violations Killing of Nawab Bugti Causes of Baloch Disaffection a) Richest in Resources, Yet the Poorest Province b) Lack of Representation c) The case for Autonomy d) Development as Colonisation The Future The Weaknesses The Road Ahead Endnotes ABSTRACT The Balochis, like the Kurds, their cousins from Aleppo, do not have a sovereign state of their own. -

S. No. Folio No. Security Holder Name Father's/Husband's Name Address

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders without / invalid CNIC # as of 31-12-2019 S. Folio No. Security Holder Name Father's/Husband's Name Address No. of No. Securities 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN S/O MR. MOHAMMAD WAZIR KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI S/O MR. MOHD ABDUL HAFEEZ 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3,280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN S/O MURTUZA MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD MR. HAMID HUSSAIN C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE S/O A. RAHIM B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9,382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED S/O GHULAM QADDIR KHAN H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN S/O MOHD NASRULLAH KHAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA S/O FAZAL-I-MAHMOOD 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1,919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN S/O ABDUR REHMAN KHAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8,530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN SARDAR M. FAROOQ IBRAHIM 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5,945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN S/O KH. -

The Pakistan Army Officer Corps, Islam and Strategic Culture 1947-2007

The Pakistan Army Officer Corps, Islam and Strategic Culture 1947-2007 Mark Fraser Briskey A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UNSW School of Humanities and Social Sciences 04 July 2014 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT 'I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). I have either used no substantial portions of copyright material in my thesis or I have obtained permission to use copyright material; where permission has not been granted I have applied/ ·11 apply for a partial restriction of the digital copy of my thesis or dissertation.' Signed t... 11.1:/.1!??7 Date ...................... /-~ ....!VP.<(. ~~~-:V.: .. ......2 .'?. I L( AUTHENTICITY STATEMENT 'I certify that the Library deposit digital copy is a direct equivalent of the final officially approved version of my thesis. No emendation of content has occurred and if there are any minor Y, riations in formatting, they are the result of the conversion to digital format.' · . /11 ,/.tf~1fA; Signed ...................................................../ ............... Date . -

Kamal Ram Gurjar

Kamal Ram Gurjar (17 December 1924 – 1 July 1982) King George VI pinning the Victoria Cross on Sepoy Kamal Ram, 26 July 1944 (IWM NA17270) Sepoy Kamal Ram VC was an Indian recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces. He was the second-youngest Indian recipient of the award. Kamal Ram Gurjar was born into a Gurjar family on 17 December 1924, at Bindapura, Bholupura, village of Karauli District, Rajasthan, India. His father's name was Shiv Chand Gurjar. During World War II, he served in the 3rd Battalion, 8th Punjab Regiment, British Indian Army (now the 3rd Battalion, Baloch Regiment, Pakistan Army). He was 19 years old, with the rank of Sepoy, when, on 12 May 1944, his battalion assaulted the formidable German defences of the Gustav Line, across the River Gari in Italy; and he performed the deeds for which he was awarded the VC. King George VI presented him with the medal in Italy in 1944. He later rose to the rank of Subedar. He died in 1982. The citation reads as follows: The KING has been graciously pleased to approve the award of the VICTORIA CROSS to:– No. 35408 Sepoy Kamal Ram, 8th Punjab Regiment, Indian Army. In Italy, on 12 May 1944, after crossing the River Gari overnight, the Company advance was held up by heavy machine-gun fire from four posts on the front and flanks. As the capture of the position was essential to secure the bridgehead, the Company Commander called for a volunteer to get round the rear of the right post and silence it. -

Imperial Influence on the Postcolonial Indian Army, 1945-1973

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2017 Imperial Influence On The oP stcolonial Indian Army, 1945-1973 Robin James Fitch-McCullough University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Fitch-McCullough, Robin James, "Imperial Influence On The osP tcolonial Indian Army, 1945-1973" (2017). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 763. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/763 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMPERIAL INFLUENCE ON THE POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN ARMY, 1945-1973 A Thesis Presented by Robin Fitch-McCullough to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History October, 2017 Defense Date: May 4th, 2016 Thesis Examination Committee: Abigail McGowan, Ph.D, Advisor Paul Deslandes, Ph.D, Chairperson Pablo Bose, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College ABSTRACT The British Indian Army, formed from the old presidency armies of the East India Company in 1895, was one of the pillars upon which Britain’s world empire rested. While much has been written on the colonial and global campaigns fought by the Indian Army as a tool of imperial power, comparatively little has been written about the transition of the army from British to Indian control after the end of the Second World War. -

“Dreams Turned Into Nightmares” Attacks on Students, Teachers, and Schools in Pakistan WATCH

H U M A N R I G H T S “Dreams Turned into Nightmares” Attacks on Students, Teachers, and Schools in Pakistan WATCH “Dreams Turned into Nightmares” Attacks on Students, Teachers, and Schools in Pakistan Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34518 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MARCH 2017 ISBN: 978-1-6231-34518 “Dreams Turned into Nightmares” Attacks on Students, Teachers, and Schools in Pakistan Map .................................................................................................................................... I Glossary ............................................................................................................................. II Summary .......................................................................................................................... -

Balochistan: Continuing Violence and Its Implications

Balochistan: Continuing Violence and Its Implications Alok Bansal Abstract State-building efforts in Pakistan have been increasingly come under challenge from ethno-national movements. The current spate of insurgency in Balochistan is a product of repressive policies coupled with historical grievances that have led to increased alienation amongst the Baloch and a general perception that they are being exploited. The continuing violence has the potential to destabilise not only Pakistan but the entire region. Stability and peace in Balochistan is not only crucial For Pakistan but to India as well since it is a critical area through which both the Iran-Pakistan-India as well as the Central Asian energy pipelines will traverse in the future. India needs to carefully monitor the trajectory of the Baloch movement and be prepared for events that may impinge on its policies towards energy flows. “It is not the ’70s and we will not climb mountains behind them, they will even not know what and from where something has come and hit them” General Pervez Musharraf1 “If it is not the seventies for us, it is also not the seventies for them. If there is any change, it will be for all. If we have to face severe consequences of a change, then they will also not be in a comfortable position” Sardar Ataullah Mengal2 On December 17, 2005, the Pakistani troops launched a full-fledged operation against Baloch insurgents in Kohlu District – an area dominated by Marri tribesmen, the most belligerent of the Baloch tribes. This was the Strategic Analysis, Vol. 30, No.