Cultural Intelligence for Military Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders (W/Out Cnic) As of December 31, 2017

ASKARI BANK LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS (W/OUT CNIC) AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2017 S. NO. FOLIO NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDERS ADDRESSES OF THE SHAREHOLDERS NO. OF SHARES 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN C/O BANK OF AMERICA, BLUE AREA, ISLAMABAD. 2878 12 68 MR. WASEEM AHMED HOUSE NO.485, STREET NO.17, CHAKLALA SCHEME-III, RAWALPINDI. 5945 13 71 MS. SHAMEEM QUAVI SIDDIQUI 112/1, 13TH STREET, PHASE-VI, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, KARACHI-75500. 2695 14 74 MS. YAZDANI BEGUM HOUSE NO.A-75, BLOCK-13, GULSHAN-E-IQBAL, KARACHI. -

Pakistan: Death Plot Against Human Rights Lawyer, Asma Jahangir

UA: 164/12 Index: ASA 33/008/2012 Pakistan Date: 7 June 2012 URGENT ACTION DEATH PLOT AGAINST HUMAN RIGHTS LAWYER Leading human rights lawyer and activist Asma Jahangir fears for her life, having just learned of a plot by Pakistan’s security forces to kill her. Killings of human rights defenders have increased over the last year, many of which implicate Pakistan’s Inter- Service Intelligence agency (ISI). On 4 June, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) alerted Amnesty International to information it had received of a plot by Pakistan’s security forces to kill HRCP founder and human rights lawyer Asma Jahangir. As Pakistan’s leading human rights defender, Asma Jahangir has been threatened many times before. However news of the plot to kill her is altogether different. The information available does not appear to have been intentionally circulated as means of intimidation, but leaked from within Pakistan’s security apparatus. Because of this, Asma Jahangir believes the information is highly credible and has therefore not moved from her home. Please write immediately in English, Urdu, or your own language, calling on the Pakistan authorities to: Immediately provide effective security to Asma Jahangir. Promptly conduct a full investigation into alleged plot to kill her, including all individuals and institutions suspected of being involved, including the Inter-Services Intelligence agency. Bring to justice all suspected perpetrators of attacks on human rights defenders, in trials that meet international fair trial standards and -

SELF-DETERMINATION OUTSIDE the COLONIAL CONTEXT: the BIRTH of BANGLADESH in Retrospectt

SELF-DETERMINATION OUTSIDE THE COLONIAL CONTEXT: THE BIRTH OF BANGLADESH IN RETROSPECTt By VedP. Nanda* I. INTRODUCTION In the aftermath of the Indo-Pakistan War in December 1971, the independent nation-state of Bangladesh was born.' Within the next four months, more than fifty countries had formally recognized the new nation.2 As India's military intervention was primarily responsible for the success of the secessionist movement in what was then known as East Pakistan, and for the creation of a new political entity on the inter- national scene,3 many serious questions stemming from this historic event remain unresolved for the international lawyer. For example: (1) What is the continuing validity of Article 2 (4) of the United Nations Charter?4 (2) What is the current status of the doctrine of humanita- rian intervention in international law?5 (3) What action could the United Nations have taken to avert the Bangladesh crisis?6 (4) What measures are necessary to prevent such tragic occurrences in the fu- ture?7 and (5) What relationship exists between the principle of self- "- This paper is an adapted version of a chapter that will appear in Y. ALEXANDER & R. FRIEDLANDER, SELF-DETERMINATION (1979). * Professor of Law and Director of the International Legal Studies Program, Univer- sity of Denver Law Center. 1. See generally BANGLADESH: CRISIS AND CONSEQUENCES (New Delhi: Deen Dayal Research Institute 1972); D. MANKEKAR, PAKISTAN CUT TO SIZE (1972); PAKISTAN POLITI- CAL SYSTEM IN CRISIS: EMERGENCE OF BANGLADESH (S. Varma & V. Narain eds. 1972). 2. Ebb Tide, THE ECONOMIST, April 8, 1972, at 47. -

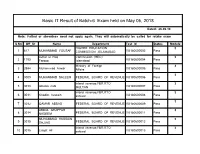

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam Held on May 05, 2018

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam S.No Off_Sr Name Department Test Id Status Module HIGHER EDUCATION 3 1 617 MUHAMMAD YOUSAF COMMISSION ,ISLAMABAD VU180600002 Pass Azhar ul Haq Commission (HEC) 3 2 1795 Farooq Islamabad VU180600004 Pass Ministry of Foreign 3 3 2994 Muhammad Anwar Affairs VU180600005 Pass 3 4 3009 MUHAMMAD SALEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600006 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 5 3010 Ghulan nabi MULTAN VU180600007 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 6 3011 Khadim hussain sahiwal VU180600008 Pass 3 7 3012 QAMAR ABBAS FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600009 Pass ABDUL GHAFFAR 3 8 3014 NADEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600011 Pass MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN 3 9 3015 SAJJAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600012 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 10 3016 Liaqat Ali sahiwal VU180600013 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 11 3017 Tariq javed sahiwal VU180600014 Pass 3 12 3018 AFTAB AHMAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600015 Pass Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Muhammad inam-ul- inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 13 3019 haq MULTAN VU180600016 Pass Ministry of Defense (Defense Division) 3 Rawalpindi. 14 4411 Asif Mehmood VU180600018 Pass 3 15 4631 Rooh ul Amin Pakistan Air Force VU180600022 Pass Finance/Income Tax 3 16 4634 Hammad Qureshi Department VU180600025 Pass Federal Board Of Revenue 3 17 4635 Arshad Ali Regional Tax-II VU180600026 Pass 3 18 4637 Muhammad Usman Federal Board Of Revenue VU180600027 -

Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 4 PASHTO, WANECI, ORMURI Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 4 Pashto Waneci Ormuri Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2004 ISBN 969-8023-14-3 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface.............................................................................................................vii Maps................................................................................................................ -

Consolidated List of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

Consolidated list of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments List of HBL Branches for payments in Punjab, Sindh and Balochistan ranch Cod Branch Name Branch Address Cluster District Tehsil 0662 ATTOCK-CITY 22 & 23 A-BLOCK CHOWK BAZAR ATTOCK CITY Cluster-2 ATTOCK ATTOCK BADIN-QUAID-I-AZAM PLOT NO. A-121 & 122 QUAID-E-AZAM ROAD, FRUIT 1261 ROAD CHOWK, BADIN, DISTT. BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL TANDO GHULAM ALI 1661 MALTI, DISTT BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL MALTI, 1661 TANDO GHULAM ALI Cluster-3 Badin Badin DISTT BADIN CHISHTIAN-GHALLA SHOP NO. 38/B, KHEWAT NO. 165/165, KHATOONI NO. 115, MANDI VILLAGE & TEHSIL CHISHTIAN, DISTRICT BAHAWALNAGAR. 0105 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR KHEWAT,NO.6-KHATOONI NO.40/41-DUNGA BONGA DONGA BONGA HIGHWAY ROAD DISTT.BWN 1626 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR-TEHSIL 0677 442-Chowk Rafique shah TEHSIL BAZAR BAHAWALNAGAR Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAZAR BAHAWALPUR-GHALLA HOUSE # B-1, MODEL TOWN-B, GHALLA MANDI, TEHSIL & 0870 MANDI DISTRICT BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR Khewat #33 Khatooni #133 Hasilpur Road, opposite Bus KHAIRPUR TAMEWALI 1379 Stand, Khairpur Tamewali Distt Bahawalpur Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR KHEWAT 12, KHATOONI 31-23/21, CHAK NO.56/DB YAZMAN YAZMAN-MAIN BRANCH 0468 DISTT. BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR-SATELLITE Plot # 55/C Mouza Hamiaytian taxation # VIII-790 Satellite Town 1172 Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR TOWN Bahawalpur 0297 HAIDERABAD THALL VILL: & P.O.HAIDERABAD THAL-K/5950 BHAKKAR Cluster-2 BHAKKAR BHAKKAR KHASRA # 1113/187, KHEWAT # 159-2, KHATOONI # 503, DARYA KHAN HASHMI CHOWK, POST OFFICE, TEHSIL DARYA KHAN, 1326 DISTRICT BHAKKAR. -

Pakistan: Arrival and Departure

01-2180-2 CH 01:0545-1 10/13/11 10:47 AM Page 1 stephen p. cohen 1 Pakistan: Arrival and Departure How did Pakistan arrive at its present juncture? Pakistan was originally intended by its great leader, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, to transform the lives of British Indian Muslims by providing them a homeland sheltered from Hindu oppression. It did so for some, although they amounted to less than half of the Indian subcontinent’s total number of Muslims. The north Indian Muslim middle class that spearheaded the Pakistan movement found itself united with many Muslims who had been less than enthusiastic about forming Pak- istan, and some were hostile to the idea of an explicitly Islamic state. Pakistan was created on August 14, 1947, but in a decade self-styled field marshal Ayub Khan had replaced its shaky democratic political order with military-guided democracy, a market-oriented economy, and little effective investment in welfare or education. The Ayub experiment faltered, in part because of an unsuccessful war with India in 1965, and Ayub was replaced by another general, Yahya Khan, who could not manage the growing chaos. East Pakistan went into revolt, and with India’s assistance, the old Pakistan was bro- ken up with the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. The second attempt to transform Pakistan was short-lived. It was led by the charismatic Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who simultaneously tried to gain control over the military, diversify Pakistan’s foreign and security policy, build a nuclear weapon, and introduce an economic order based on both Islam and socialism. -

Pakistan S Strategic Blunder at Kargil, by Brig Gurmeet

Pakistan’s Strategic Blunder at Kargil Gurmeet Kanwal Cause of Conflict: Failure of 10 Years of Proxy War India’s territorial integrity had not been threatened seriously since the 1971 War as it was threatened by Pakistan’s ill-conceived military adventure across the Line of Control (LoC) into the Kargil district of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) in the summer months of 1999. By infiltrating its army soldiers in civilian clothes across the LoC, to physically occupy ground on the Indian side, Pakistan added a new dimension to its 10-year-old ‘proxy war’ against India. Pakistan’s provocative action compelled India to launch a firm but measured and restrained military operation to clear the intruders. Operation ‘Vijay’, finely calibrated to limit military action to the Indian side of the LoC, included air strikes from fighter-ground attack (FGA) aircraft and attack helicopters. Even as the Indian Army and the Indian Air Force (IAF) employed their synergised combat potential to eliminate the intruders and regain the territory occupied by them, the government kept all channels of communication open with Pakistan to ensure that the intrusions were vacated quickly and Pakistan’s military adventurism was not allowed to escalate into a larger conflict. On July 26, 1999, the last of the Pakistani intruders was successfully evicted. Why did Pakistan undertake a military operation that was foredoomed to failure? Clearly, the Pakistani military establishment was becoming increasingly frustrated with India’s success in containing the militancy in J&K to within manageable limits and saw in the Kashmiri people’s open expression of their preference for returning to normal life, the evaporation of all their hopes and desires to bleed India through a strategy of “a thousand cuts”. -

Police Organisations in Pakistan

HRCP/CHRI 2010 POLICE ORGANISATIONS IN PAKISTAN Human Rights Commission CHRI of Pakistan Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative working for the practical realisation of human rights in the countries of the Commonwealth Human Rights Commission of Pakistan The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) is an independent, non-governmental organisation registered under the law. It is non-political and non-profit-making. Its main office is in Lahore. It started functioning in 1987. The highest organ of HRCP is the general body comprising all members. The general body meets at least once every year. Executive authority of this organisation vests in the Council elected every three years. The Council elects the organisation's office-bearers - Chairperson, a Co-Chairperson, not more than five Vice-Chairpersons, and a Treasurer. No office holder in government or a political party (at national or provincial level) can be an office bearer of HRCP. The Council meets at least twice every year. Besides monitoring human rights violations and seeking redress through public campaigns, lobbying and intervention in courts, HRCP organises seminars, workshops and fact-finding missions. It also issues monthly Jehd-i-Haq in Urdu and an annual report on the state of human rights in the country, both in English and Urdu. The HRCP Secretariat is headed by its Secretary General I. A. Rehman. The main office of the Secretariat is in Lahore and branch offices are in Karachi, Peshawar and Quetta. A Special Task Force is located in Hyderabad (Sindh) and another in Multan (Punjab), HRCP also runs a Centre for Democratic Development in Islamabad and is supported by correspondents and activists across the country. -

Checklist of Medicinal Flora of Tehsil Isakhel, District Mianwali-Pakistan

Ethnobotanical Leaflets 10: 41-48. 2006. Check List of Medicinal Flora of Tehsil Isakhel, District Mianwali-Pakistan Mushtaq Ahmad, Mir Ajab Khan, Shabana Manzoor, Muhammad Zafar And Shazia Sultana Department of Biological Sciences, Quaid-I-Azam University Islamabad-Pakistan Issued 15 February 2006 ABSTRACT The research work was conducted in the selected areas of Isakhel, Mianwali. The study was focused for documentation of traditional knowledge of local people about use of native medicinal plants as ethnomedicines. The method followed for documentation of indigenous knowledge was based on questionnaire. The interviews were held in local community, to investigate local people and knowledgeable persons, who are the main user of medicinal plants. The ethnomedicinal data on 55 plant species belonging to 52 genera of 30 families were recorded during field trips from six remote villages of the area. The check list and ethnomedicinal inventory was developed alphabetically by botanical name, followed by local name, family, part used and ethnomedicinal uses. Plant specimens were collected, identified, preserved, mounted and voucher was deposited in the Department of Botany, University of Arid Agriculture Rawalpindi, for future references. Key words: Checklist, medicinal flora and Mianwali-Pakistan. INTRODUCTION District Mianwali derives its name from a local Saint, Mian Ali who had a small hamlet in the 16th century which came to be called Mianwali after his name (on the eastern bank of Indus). The area was a part of Bannu district. The district lies between the 32-10º to 33-15º, north latitudes and 71-08º to 71-57º east longitudes. The district is bounded on the north by district of NWFP and Attock district of Punjab, on the east by Kohat districts, on the south by Bhakkar district of Punjab and on the west by Lakki, Karak and Dera Ismail Khan District of NWFP again. -

Pakistan's Army

Pakistan’s Army: New Chief, traditional institutional interests Introduction A year after speculation about the names of those in the race for selection as the new Army Chief of Pakistan began, General Qamar Bajwa eventually took charge as Pakistan's 16th Chief of Army Staff on 29th of November 2016, succeeding General Raheel Sharif. Ordinarily, such appointments in the defence services of countries do not generate much attention, but the opposite holds true for Pakistan. Why this is so is evident from the popular aphorism, "while every country has an army, the Pakistani Army has a country". In Pakistan, the army has a history of overshadowing political landscape - the democratically elected civilian government in reality has very limited authority or control over critical matters of national importance such as foreign policy and security. A historical background The military in Pakistan is not merely a human resource to guard the country against the enemy but has political wallop and opinions. To know more about the power that the army enjoys in Pakistan, it is necessary to examine the times when Pakistan came into existence in 1947. In 1947, both India and Pakistan were carved out of the British Empire. India became a democracy whereas Pakistan witnessed several military rulers and still continues to suffer from a severe civil- military imbalance even after 70 years of its birth. During India’s war of Independence, the British primarily recruited people from the Northwest of undivided India which post partition became Pakistan. It is noteworthy that the majority of the people recruited in the Pakistan Army during that period were from the Punjab martial races. -

Newsletter – April 2008

Newsletter – April 2008 Syed Yousaf Raza Gillani sworn in as Hon. Dr Fahmida Mirza takes her seat th 24 Prime Minister of Pakistan as Pakistan’s first woman Speaker On 24 March Syed Yousaf A former doctor made history Raza Gillani was elected in Pakistan on 19 March by as the Leader of the becoming the first woman to House by the National be elected Speaker in the Assembly of Pakistan and National Assembly of the next day he was Pakistan. Fahmida Mirza won sworn in as the 24th 249 votes in the 342-seat Lower House of parliament. Prime Minister of Pakistan. “I am honoured and humbled; this chair carries a big Born on 9 June 1952 in responsibility. I am feeling that responsibility today and Karachi, Gillani hails from will, God willing, come up to expectations.” Multan in southern Punjab and belongs to a As Speaker, she is second in the line of succession to prominent political family. His grandfather and the President and occupies fourth position in the Warrant grand-uncles joined the All India Muslim League of Precedence, after the President, the Prime Minister and were signatories of the historical Pakistan and the Chairman of Senate. Resolution passed on 23 March 1940. Mr Gillani’s father, Alamdar Hussain Gillani served as a Elected three times to parliament, she is one of the few Provincial Minister in the 1950s. women to have been voted in on a general seat rather than one reserved for women. Mr Yousaf Raza Gillani joined politics at the national level in 1978 when he became a member Fahmida Mirza 51, hails from Badin in Sindh and has of the Muslim League’s central leadership.