Pakistan: Arrival and Departure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maritime Security • Maritime

MAKING WAVES A maritime news brief covering: MARITIME SECURITY MARITIME FORCES SHIPPING, PORTS AND OCEAN ECONOMY MARINE ENVIRONMENT GEOPOLITICS Making Waves 15 - 21 Feb 2021 CONTENTS MARITIME SECURITY ................................................................................ 3 REPORTS OF INDIAN NAVY PART OF IRAN-RUSSIA MARITIME DRILL FALSE ..................................................................................... 3 INDONESIA AND CHINA FACE OFF OVER INCREASING MARITIME INTRUSIONS ............................................................................ 3 JOINT PRESS STATEMENT ON OFFICIAL VISIT OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS MINISTER OF INDIA TO THE MALDIVES ........................................ 8 INDIA, AUSTRALIA, JAPAN, US HOLD QUAD MEET, DISCUSS RULES- BASED ORDER, MYANMAR COUP................................................. 11 THE POWER OF EXAMPLE: AMERICA’S PRESENCE IN DIEGO GARCIA . 12 MARITIME FORCES ................................................................................... 15 EGYPT, SPAIN NAVIES CONDUCT JOINT DRILLS IN RED SEA ............ 15 IDEX 2021: SAUDI ARABIA TO INVEST MORE THAN $20B IN ITS MILITARY INDUSTRY OVER NEXT DECADE..................................... 15 FRANCE REJOINS JAPAN IN N. KOREA SURVEILLANCE IN E. CHINA SEA ....................................................................................... 16 SHIPPING, PORTS AND OCEAN ECONOMY ......................................... 18 INDIA SIGNS FREE TRADE PACT WITH MAURITIUS, THE FIRST OF ITS KIND WITH AFRICAN NATION .................................................. -

Pakistan: Death Plot Against Human Rights Lawyer, Asma Jahangir

UA: 164/12 Index: ASA 33/008/2012 Pakistan Date: 7 June 2012 URGENT ACTION DEATH PLOT AGAINST HUMAN RIGHTS LAWYER Leading human rights lawyer and activist Asma Jahangir fears for her life, having just learned of a plot by Pakistan’s security forces to kill her. Killings of human rights defenders have increased over the last year, many of which implicate Pakistan’s Inter- Service Intelligence agency (ISI). On 4 June, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) alerted Amnesty International to information it had received of a plot by Pakistan’s security forces to kill HRCP founder and human rights lawyer Asma Jahangir. As Pakistan’s leading human rights defender, Asma Jahangir has been threatened many times before. However news of the plot to kill her is altogether different. The information available does not appear to have been intentionally circulated as means of intimidation, but leaked from within Pakistan’s security apparatus. Because of this, Asma Jahangir believes the information is highly credible and has therefore not moved from her home. Please write immediately in English, Urdu, or your own language, calling on the Pakistan authorities to: Immediately provide effective security to Asma Jahangir. Promptly conduct a full investigation into alleged plot to kill her, including all individuals and institutions suspected of being involved, including the Inter-Services Intelligence agency. Bring to justice all suspected perpetrators of attacks on human rights defenders, in trials that meet international fair trial standards and -

Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Politics of Exclusion: Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan by Sadia Saeed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor George P. Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Fatma Muge Gocek Associate Professor Genevieve Zubrzycki Professor Mamadou Diouf, Columbia University © Sadia Saeed 2010 2 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents with my deepest love, respect and gratitude for the innumerable ways they have supported my work and choices. ii Acknowledgements I would like to begin by acknowledging the immense support my parents have given me every step of the way during my (near) decade in graduate school. I have dedicated this dissertation to them. My ammi and baba have always believed in my capabilities to accomplish not only this dissertation but much more in life and their words of love and encouragement have continuously given me the strength and the will to give my research my very best. My father‘s great enthusiasm for this project, his intellectual input and his practical help and advice during the fieldwork of this project have been formative to this project. I would like to thank my dissertation advisor George Steinmetz for the many engaged conversations about theory and methods, for always pushing me to take my work to the next level and above all for teaching me to recognize and avoid sloppiness, caricatures and short-cuts. It is to him that I owe my greatest intellectual debt. -

SSC-SUPPL-2018-RESULT.Pdf

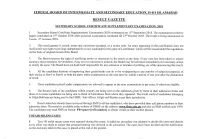

FBISE - Computer Section FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, ISLAMABAD 1 RESULT GAZETTE OF SSC-II SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2018 SALIENT FEATURES OF RESULT ALL AREAS G r a d e W i s e D i s t r i b u t i o n Pass Sts. / Grp. / Gender Enrolled Absent Appd. R.L. UFM Fail Pass A1 A B C D E %age G.P.A EX/PRIVATE CANDIDATES Male 6965 132 6833 16 5 3587 3241 97 112 230 1154 1585 56 47.43 1.28 Female 2161 47 2114 12 1 893 1220 73 63 117 625 335 7 57.71 1.78 1 SCIENCE Total : 9126 179 8947 28 6 4480 4461 170 175 347 1779 1920 63 49.86 1.40 Male 1086 39 1047 2 1 794 252 0 2 7 37 159 45 24.07 0.49 Female 1019 22 997 4 3 614 380 1 0 18 127 217 16 38.11 0.91 2 HUMANITIES Total : 2105 61 2044 6 4 1408 632 1 2 25 164 376 61 30.92 0.70 Total : 11231 240 10991 34 10 5888 5093 171 177 372 1943 2296 124 46.34 1.27 Grand Total : 11231 240 10991 34 10 5888 5093 171 177 372 1943 2296 124 46.34 1.27 FBISE - Computer Section FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, ISLAMABAD 2 RESULT GAZETTE OF SSC-II SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2018 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE GAZETTE Subjects EHE:I ESSENTIAL OF HOME ECONOMICS - I PST-II PAKISTAN STUDIES - II (HIC) AMD:I ART AND MODEL DRAWING - I EHE:II ESSENTIAL OF HOME ECONOMICS - II U-C:I URDU COMPULSORY - I AMD:I ART AND MODEL DRAWING - I (HIC) F-N:I FOOD AND NUTRITION - I U-C:I URDU COMPULSORY - I (HIC) AMD:II ART AND MODEL DRAWING - II F-N:II FOOD AND NUTRITION - II U-C:II URDU COMPULSORY - II AMD:II ART AND MODEL DRAWING - II (HIC) G-M:I MATHEMATICS (GEN.) - I U-C:II URDU COMPULSORY - II (HIC) ARB:I ARABIC - I G-M:II MATHEMATICS (GEN.) - II U-S URDU SALEES (IN LIEU OF URDU II) ARB:II ARABIC - II G-S:I GENERAL SCIENCE - I WEL:I WELDING (ARC & GAS) - I BIO:I BIOLOGY - I G-S:I GENERAL SCIENCE - I (HIC) WEL:II WELDING (ARC AND GAS) - II BIO:II BIOLOGY - II G-S:II GENERAL SCIENCE - II WWF:I WOOD WORKING AND FUR. -

SELF-DETERMINATION OUTSIDE the COLONIAL CONTEXT: the BIRTH of BANGLADESH in Retrospectt

SELF-DETERMINATION OUTSIDE THE COLONIAL CONTEXT: THE BIRTH OF BANGLADESH IN RETROSPECTt By VedP. Nanda* I. INTRODUCTION In the aftermath of the Indo-Pakistan War in December 1971, the independent nation-state of Bangladesh was born.' Within the next four months, more than fifty countries had formally recognized the new nation.2 As India's military intervention was primarily responsible for the success of the secessionist movement in what was then known as East Pakistan, and for the creation of a new political entity on the inter- national scene,3 many serious questions stemming from this historic event remain unresolved for the international lawyer. For example: (1) What is the continuing validity of Article 2 (4) of the United Nations Charter?4 (2) What is the current status of the doctrine of humanita- rian intervention in international law?5 (3) What action could the United Nations have taken to avert the Bangladesh crisis?6 (4) What measures are necessary to prevent such tragic occurrences in the fu- ture?7 and (5) What relationship exists between the principle of self- "- This paper is an adapted version of a chapter that will appear in Y. ALEXANDER & R. FRIEDLANDER, SELF-DETERMINATION (1979). * Professor of Law and Director of the International Legal Studies Program, Univer- sity of Denver Law Center. 1. See generally BANGLADESH: CRISIS AND CONSEQUENCES (New Delhi: Deen Dayal Research Institute 1972); D. MANKEKAR, PAKISTAN CUT TO SIZE (1972); PAKISTAN POLITI- CAL SYSTEM IN CRISIS: EMERGENCE OF BANGLADESH (S. Varma & V. Narain eds. 1972). 2. Ebb Tide, THE ECONOMIST, April 8, 1972, at 47. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Prime Minister Muhammad Nawaz Sharif and Former President Asif

Prime Minister Muhammad Nawaz Sharif and former President Asif Ali Zardari jointly performed ground-breaking of the US 1.6 billion dollar Thar Coal Mining & Power Project of Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company (SECMC)on Friday, 31st January, 2014 at Thar Coalfield Block-II near Islamkot. The project of Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company will initially provide 660 MW of power for Pakistan’s energy starved industrial units. It will complete in 2017 and help spur economic development and bring energy security to the country. The two leaders of PMLN and PPP performed the ground-breaking of the project that will be carried out by Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company (SECMC) - a joint venture between Government of Sindh and Engro Corp. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, in his address said the launch of the project along with Asif Ali Zardari, had sent a message across that the political leadership should be united when it comes to the development of the country. He said this political trend must be set in Pakistan now and the leaders need to think about the country first regardless of their differences. He thanked former President Asif Zardari for inviting him to the ground-breaking of the Thar Coal project and said it was a matter of satisfaction that “we all are together and have the same priorities. Anyone who believes in the development of Pakistan, would be pleased that the country’s political leadership is together on this national event.” Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif termed the Thar Coal project a big national development project and suggested that the coal for all projects in Gaddani should be supplied from Thar. -

Imports-Exports Enterprise’: Understanding the Nature of the A.Q

Not a ‘Wal-Mart’, but an ‘Imports-Exports Enterprise’: Understanding the Nature of the A.Q. Khan Network Strategic Insights , Volume VI, Issue 5 (August 2007) by Bruno Tertrais Strategic Insights is a bi-monthly electronic journal produced by the Center for Contemporary Conflict at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. The views expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of NPS, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. Introduction Much has been written about the A.Q. Khan network since the Libyan “coming out” of December 2003. However, most analysts have focused on the exports made by Pakistan without attempting to relate them to Pakistani imports. To understand the very nature of the network, it is necessary to go back to its “roots,” that is, the beginnings of the Pakistani nuclear program in the early 1970s, and then to the transformation of the network during the early 1980s. Only then does it appear clearly that the comparison to a “Wal-Mart” (the famous expression used by IAEA Director General Mohammed El-Baradei) is not an appropriate description. The Khan network was in fact a privatized subsidiary of a larger, State-based network originally dedicated to the Pakistani nuclear program. It would be much better characterized as an “imports-exports enterprise.” I. Creating the Network: Pakistani Nuclear Imports Pakistan originally developed its nuclear complex out in the open, through major State-approved contracts. Reprocessing technology was sought even before the launching of the military program: in 1971, an experimental facility was sold by British Nuclear Fuels Ltd (BNFL) in 1971. -

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’S Posture Toward Afghanistan Since 2001

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’s Posture toward Afghanistan since 2001 Since the terrorist at- tacks of September 11, 2001, Pakistan has pursued a seemingly incongruous course of action in Afghanistan. It has participated in the U.S. and interna- tional intervention in Afghanistan both by allying itself with the military cam- paign against the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida and by serving as the primary transit route for international military forces and matériel into Afghanistan.1 At the same time, the Pakistani security establishment has permitted much of the Afghan Taliban’s political leadership and many of its military command- ers to visit or reside in Pakistani urban centers. Why has Pakistan adopted this posture of Afghan Taliban accommodation despite its nominal participa- tion in the Afghanistan intervention and its public commitment to peace and stability in Afghanistan?2 This incongruence is all the more puzzling in light of the expansion of insurgent violence directed against Islamabad by the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a coalition of militant organizations that are independent of the Afghan Taliban but that nonetheless possess social and po- litical links with Afghan cadres of the Taliban movement. With violence against Pakistan growing increasingly indiscriminate and costly, it remains un- clear why Islamabad has opted to accommodate the Afghan Taliban through- out the post-2001 period. Despite a considerable body of academic and journalistic literature on Pakistan’s relationship with Afghanistan since 2001, the subject of Pakistani accommodation of the Afghan Taliban remains largely unaddressed. Much of the existing literature identiªes Pakistan’s security competition with India as the exclusive or predominant driver of Pakistani policy vis-à-vis the Afghan Khalid Homayun Nadiri is a Ph.D. -

Pakistan, Country Information

Pakistan, Country Information PAKISTAN ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VI HUMAN RIGHTS VIA. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB. HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC. HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS AND OTHER GROUPS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Pakistan.htm[10/21/2014 9:56:32 AM] Pakistan, Country Information General 2.1 The Islamic Republic of Pakistan lies in southern Asia, bordered by India to the east and Afghanistan and Iran to the west. -

1. Syed Khalid Siraj Subhani 2. Mian Asad Hayaud

PROFILE OF CANDIDATES WHO HAVE FILED THEIR INTENTION TO OFFER THEMSELVES TO CONTEST IN THE ELECTION OF DIRECTORS AT THE 11th EXTRAORDINARY GENERAL MEETING SCHEDULED TO BE HELD ON MARCH 17, 2021. 1. Syed Khalid Siraj Subhani Mr. Subhani is a Chemical Engineer with Executive Management Program from Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley and Leadership program from MIT, Boston. A seasoned executive, his career spanned over 33 years with Exxon Chemical Pakistan Limited, which subsequently became Engro Chemical Pakistan Limited and later Engro Corporation Limited. This included long term assignments with Esso Chemical Canada in Edmonton and at ICI site in Billingham UK. Over the years, he worked in numerous senior executive positions at Engro and played instrumental role in growth and diversification of the company to make it one of the largest business conglomerates of Pakistan. Prior to retirement from Engro he worked as President and Chief Executive Officer of Engro Corporation Limited, Engro Fertilisers Limited and Engro Polymer and Chemicals Limited. Mr. Subhani also served as President and Chief Executive Officer of ThalNova Power Thar Private Limited for a period of two years. Earlier Mr. Subhani also served on the board of Engro Corporation Limited (Director), Hub Power Company Limited (Director), Engro Foods Limited (Director), Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company Limited (Director), Laraib Energy Limited (Director), Engro Fertilisers Limited (Board Chairman), Engro Polymer and Chemicals Limited (Board Chairman), Engro Vopak Terminal Limited (Board Chairman), Thar Power Company Limited (Board Chairman), Engro Powergen Qadirpur Limited (Board Chairman), Engro Elengy Terminal (Private) Limited (Board Chairman) and Engro Eximp Agri Products (Private) Limited (Board Chairman). -

Pakistan's 2008 Elections

Pakistan’s 2008 Elections: Results and Implications for U.S. Policy name redacted Specialist in South Asian Affairs April 9, 2008 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RL34449 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Pakistan’s 2008 Elections: Results and Implications for U.S. Policy Summary A stable, democratic, prosperous Pakistan actively working to counter Islamist militancy is considered vital to U.S. interests. Pakistan is a key ally in U.S.-led counterterrorism efforts. The history of democracy in Pakistan is a troubled one marked by ongoing tripartite power struggles among presidents, prime ministers, and army chiefs. Military regimes have ruled Pakistan directly for 34 of the country’s 60 years in existence, and most observers agree that Pakistan has no sustained history of effective constitutionalism or parliamentary democracy. In 1999, the democratically elected government of then-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was ousted in a bloodless coup led by then-Army Chief Gen. Pervez Musharraf, who later assumed the title of president. In 2002, Supreme Court-ordered parliamentary elections—identified as flawed by opposition parties and international observers—seated a new civilian government, but it remained weak, and Musharraf retained the position as army chief until his November 2007 retirement. In October 2007, Pakistan’s Electoral College reelected Musharraf to a new five-year term in a controversial vote that many called unconstitutional. The Bush Administration urged restoration of full civilian rule in Islamabad and called for the February 2008 national polls to be free, fair, and transparent. U.S. criticism sharpened after President Musharraf’s November 2007 suspension of the Constitution and imposition of emergency rule (nominally lifted six weeks later), and the December 2007 assassination of former Prime Minister and leading opposition figure Benazir Bhutto.