Balochistan: Continuing Violence and Its Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section Iv District Profiles Awaran

SECTION IV DISTRICT PROFILES AWARAN Awaran district lies in the south of the Balochistan province. Awaran is known as oasis of AGRICULTURAL INFORMATION dates. The climate is that of a desert with hot summer and mild winter. Major crops include Total cultivated area (hectares) 23,600 wheat, barley, cotton, pulses, vegetable, fodder and fruit crops. There are three tehsils in the district: Awaran, Jhal Jhao and Mashkai. The district headquarter is located at Awaran. Total non-cultivated area (hectares) 187,700 Total area under irrigation (hectares) 22,725 Major rabi crop(s) Wheat, vegetable crops SOIL ATTRIBUTES Mostly barren rocks with shallow unstable soils Major kharif crop(s) Cotton, sorghum Soil type/parent material material followed by nearly level to sloppy, moderately deep, strongly calcareous, medium Total livestock population 612,006 textured soils overlying gravels Source: Crop Reporting Services, Balochistan; Agriculture Census 2010; Livestock Census 2006 Dominant soil series Gacheri, Khamara, Winder *pH Data not available *Electrical conductivity (dS m-1) Data not available Organic matter (%) Data not available Available phosphorus (ppm) Data not available Extractable potassium (ppm) Data not available Farmers availing soil testing facility (%) 2 (Based on crop production zone wise data) Farmers availing water testing facility (%) 0 (Based on crop production zone wise data) Source: District Soil Survey Reports, Soil Survey of Pakistan Farm Advisory Centers, Fauji Fertilizer Company Limited (FFC) Inputs Use Assessment, FAO (2018) Land Cover Atlas of Balochistan (FAO, SUPARCO and Government of Balochistan) Source: Information Management Unit, FAO Pakistan *Soil pH and electrical conductivity were measured in 1:2.5, soil:water extract. -

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders (W/Out Cnic) As of December 31, 2017

ASKARI BANK LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS (W/OUT CNIC) AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2017 S. NO. FOLIO NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDERS ADDRESSES OF THE SHAREHOLDERS NO. OF SHARES 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN C/O BANK OF AMERICA, BLUE AREA, ISLAMABAD. 2878 12 68 MR. WASEEM AHMED HOUSE NO.485, STREET NO.17, CHAKLALA SCHEME-III, RAWALPINDI. 5945 13 71 MS. SHAMEEM QUAVI SIDDIQUI 112/1, 13TH STREET, PHASE-VI, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, KARACHI-75500. 2695 14 74 MS. YAZDANI BEGUM HOUSE NO.A-75, BLOCK-13, GULSHAN-E-IQBAL, KARACHI. -

ANSWERED ON:01.03.2006 USE of CHEMICAL WEAPONS by PAKISTAN Singh Shri Uday

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA EXTERNAL AFFAIRS LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO:155 ANSWERED ON:01.03.2006 USE OF CHEMICAL WEAPONS BY PAKISTAN Singh Shri Uday Will the Minister of EXTERNAL AFFAIRS be pleased to state: (a) whether Pakistani forces are using chemical weapons as reported in The Hindustan Times dated January 24, 2006; (b) if so, the facts thereof; (c) whether the use of chemical weapons by Pak forces is creating tension in the region, particularly in India; and (d) if so, the reaction of the Union Government in this regard? Answer THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS (SHRI E. AHAMED) (a) - (d) A statement is placed on the Table of the House. Statement as mentioned in reply to the Lok Sabha Question No.155 (Priority-XIV) for answer on 01.03. 2006 regarding `Use of Chemical Weapons by Pakistan` (a) - (b) It has been reported in the Pakistani media that Pakistani forces used chemical weapons in Balochistan recently. On 24 December 2005, Senator Sanaullah Baloch of the Balochistan National Party (BNP) alleged that the army was using gas and chemicals against Balochs. On 24 December 2005, Senators belonging to the nationalist parties of Balochistan accused the military of using poison gas in Kohlu, Balochistan, and of carpet bombing civilians in the area. On 7 February 2006, Mr. Agha Shahid Hasan Bugti, Secretary-General of Jamhoori Watan Party (JWP), accused the paramilitary forces of firing chemical gas shells on civilian population in Dera Bugti, Balochistan. However, on 2 January 2006, the Spokesman of the Pakistan Army, Maj. -

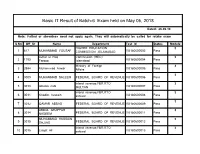

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam Held on May 05, 2018

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam S.No Off_Sr Name Department Test Id Status Module HIGHER EDUCATION 3 1 617 MUHAMMAD YOUSAF COMMISSION ,ISLAMABAD VU180600002 Pass Azhar ul Haq Commission (HEC) 3 2 1795 Farooq Islamabad VU180600004 Pass Ministry of Foreign 3 3 2994 Muhammad Anwar Affairs VU180600005 Pass 3 4 3009 MUHAMMAD SALEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600006 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 5 3010 Ghulan nabi MULTAN VU180600007 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 6 3011 Khadim hussain sahiwal VU180600008 Pass 3 7 3012 QAMAR ABBAS FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600009 Pass ABDUL GHAFFAR 3 8 3014 NADEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600011 Pass MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN 3 9 3015 SAJJAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600012 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 10 3016 Liaqat Ali sahiwal VU180600013 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 11 3017 Tariq javed sahiwal VU180600014 Pass 3 12 3018 AFTAB AHMAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600015 Pass Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Muhammad inam-ul- inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 13 3019 haq MULTAN VU180600016 Pass Ministry of Defense (Defense Division) 3 Rawalpindi. 14 4411 Asif Mehmood VU180600018 Pass 3 15 4631 Rooh ul Amin Pakistan Air Force VU180600022 Pass Finance/Income Tax 3 16 4634 Hammad Qureshi Department VU180600025 Pass Federal Board Of Revenue 3 17 4635 Arshad Ali Regional Tax-II VU180600026 Pass 3 18 4637 Muhammad Usman Federal Board Of Revenue VU180600027 -

Public Sector Development Programme 2019-20 (Original)

GOVERNMENT OF BALOCHISTAN PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT PUBLIC SECTOR DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2019-20 (ORIGINAL) Table of Contents S.No. Sector Page No. 1. Agriculture……………………………………………………………………… 2 2. Livestock………………………………………………………………………… 8 3. Forestry………………………………………………………………………….. 11 4. Fisheries…………………………………………………………………………. 13 5. Food……………………………………………………………………………….. 15 6. Population welfare………………………………………………………….. 16 7. Industries………………………………………………………………………... 18 8. Minerals………………………………………………………………………….. 21 9. Manpower………………………………………………………………………. 23 10. Sports……………………………………………………………………………… 25 11. Culture……………………………………………………………………………. 30 12. Tourism…………………………………………………………………………... 33 13. PP&H………………………………………………………………………………. 36 14. Communication………………………………………………………………. 46 15. Water……………………………………………………………………………… 86 16. Information Technology…………………………………………………... 105 17. Education. ………………………………………………………………………. 107 18. Health……………………………………………………………………………... 133 19. Public Health Engineering……………………………………………….. 144 20. Social Welfare…………………………………………………………………. 183 21. Environment…………………………………………………………………… 188 22. Local Government ………………………………………………………….. 189 23. Women Development……………………………………………………… 198 24. Urban Planning and Development……………………………………. 200 25. Power…………………………………………………………………………….. 206 26. Other Schemes………………………………………………………………… 212 27. List of Schemes to be reassessed for Socio-Economic Viability 2-32 PREFACE Agro-pastoral economy of Balochistan, periodically affected by spells of droughts, has shrunk livelihood opportunities. -

23Rd Indian Infantry Division

21 July 2012 [23 INDIAN INFANTRY DIVISION (1943)] rd 23 Indian Infantry Division (1) st 1 Indian Infantry Brigade (2) 1st Bn. The Seaforth Highlanders (Ross-shire Buffs, The Duke of Albany’s) th th 7 Bn. 14 Punjab Regiment (3) 1st Patiala Infantry (Rajindra Sikhs), Indian State Forces st 1 Bn. The Assam Regiment (4) 37th Indian Infantry Brigade 3rd Bn. 3rd Queen Alexandra’s Own Gurkha Rifles 3rd Bn. 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles (Frontier Force) 3rd Bn. 10th Gurkha Rifles 49th Indian Infantry Brigade 4th Bn. 5th Mahratta Light Infantry 5th (Napiers) Bn. 6th Rajputana Rifles nd th 2 (Berar) Bn. 19 Hyderabad Regiment (5) Divisional Troops The Shere Regiment (6) The Kali Badahur Regiment (6) th 158 Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (7) 3rd Indian Field Regiment, Indian Artillery 28th Indian Mountain Regiment, Indian Artillery nd 2 Indian Anti-Tank Regiment, Indian Artillery (8) 68th Field Company, King George V’s Own Bengal Sappers and Miners 71st Field Company, King George V’s Own Bengal Sappers and Miners 91st Field Company, Royal Bombay Sappers and Miners 323rd Field Park Company, Queen Victoria’s Own Madras Sappers and Miners 23rd Indian Divisional Signals, Indian Signal Corps 24th Indian Field Ambulance, Indian Army Medical Corps 47th Indian Field Ambulance, Indian Army Medical Corps 49th Indian Field Ambulance, Indian Army Medical Corps © www.britishmilitaryhistory.co.uk Page 1 21 July 2012 [23 INDIAN INFANTRY DIVISION (1943)] NOTES: 1. The division was formed on 1st January 1942 at Jhansi in India. In March, the embryo formation moved to Ranchi where the majority of the units joined it. -

PAKISTAN-BALOCHISTAN IPC ACUTE MALNUTRITION ANALYSIS August 2019 – Projection Until November 2019 Report # 0001 | Issued in September 2019

PAKISTAN-BALOCHISTAN IPC ACUTE MALNUTRITION ANALYSIS August 2019 – Projection until November 2019 Report # 0001 | Issued in September 2019 Key Figures August 2019 SAM* 199,811 Number of cases 395,654 MAM* Number of 6-59 months children acutely malnourished 195,843 Number of cases IN NEED OF TREATMENT GAM* 395,654 Number of cases How Severe, How Many and When – Acute malnutrition is affecting around 0.4 million under 5 children, more than half of all children age 6-59 months in the 14 drought affected districts of Balochistan, making it a major public health problem in these districts. Of the 14 drought affected districts, 1 district has extremely critical levels of acute malnutrition (IPC AMN Phase 5) while 11 have critical levels of acute malnutrition (IPC AMN Phase 4) and 2 are in Phase 3 with serious levels of acute malnutrition according to the IPC AMN scale. Around 396,000 of the approximately 738,000 children of age 6-59 months are suffering from acute malnutrition during the drought period of May-August. 2019. Where – Panjgur district is affected by extremely critical levels of acute malnutrition and is classified as being in the highest phase of 5, according to the IPC AMN scale – where about one in 3 children under 5 are suffering from acute malnutrition. Although 11 other districts have critical levels of acute malnutrition (IPC AMN Phase 4), Kachhi, Pishin, Jhal Magsi and Dera Bugti districts have acute malnutrition levels that are close to IPC AMN Phase 5 thresholds. Awaran and Gwadar districts have serious levels (IPC AMN Phase 3) of acute malnutrition. -

Pakistan's Army

Pakistan’s Army: New Chief, traditional institutional interests Introduction A year after speculation about the names of those in the race for selection as the new Army Chief of Pakistan began, General Qamar Bajwa eventually took charge as Pakistan's 16th Chief of Army Staff on 29th of November 2016, succeeding General Raheel Sharif. Ordinarily, such appointments in the defence services of countries do not generate much attention, but the opposite holds true for Pakistan. Why this is so is evident from the popular aphorism, "while every country has an army, the Pakistani Army has a country". In Pakistan, the army has a history of overshadowing political landscape - the democratically elected civilian government in reality has very limited authority or control over critical matters of national importance such as foreign policy and security. A historical background The military in Pakistan is not merely a human resource to guard the country against the enemy but has political wallop and opinions. To know more about the power that the army enjoys in Pakistan, it is necessary to examine the times when Pakistan came into existence in 1947. In 1947, both India and Pakistan were carved out of the British Empire. India became a democracy whereas Pakistan witnessed several military rulers and still continues to suffer from a severe civil- military imbalance even after 70 years of its birth. During India’s war of Independence, the British primarily recruited people from the Northwest of undivided India which post partition became Pakistan. It is noteworthy that the majority of the people recruited in the Pakistan Army during that period were from the Punjab martial races. -

Balochistan Population - 2017 1998-2017 Area Population Average Population Average Admn - Unit Trans Urban (Sq

TABLE - 5 AREA, POPULATION BY SEX, SEX RATIO, POPULATION DENSITY, URBAN PROPORTION, HOUSEHOLD SIZE AND ANNUAL GROWTH RATE OF BALOCHISTAN POPULATION - 2017 1998-2017 AREA POPULATION AVERAGE POPULATION AVERAGE ADMN - UNIT TRANS URBAN (SQ. KM.) ALL SEXES MALE FEMALE SEX RATIO DENSITY HOUSEHOLD 1998 ANNUAL GENDER PROPORTION PER SQ. KM. SIZE GROWTH RATE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 BALOCHISTAN 347,190 12,335,129 6,483,736 5,850,613 780 110.82 35.53 27.62 6.87 6,565,885 3.37 RURAL 8,928,428 4,685,756 4,242,183 489 110.46 6.80 4,997,105 3.10 URBAN 3,406,701 1,797,980 1,608,430 291 111.78 7.06 1,568,780 4.16 AWARAN DISTRICT 29,510 121,821 63,063 58,749 9 107.34 4.13 28.10 6.61 118,173 0.16 RURAL 87,584 45,438 42,138 8 107.83 6.25 118,173 -1.56 URBAN 34,237 17,625 16,611 1 106.10 7.81 - - KALAT DISTRICT 8,416 412,058 211,806 200,251 1 105.77 48.96 17.57 7.38 237,834 2.93 RURAL 339,665 175,522 164,142 1 106.93 7.39 204,040 2.71 URBAN 72,393 36,284 36,109 - 100.48 7.30 33,794 4.08 KHARAN DISTRICT 14,958 162,766 84,631 78,135 - 108.31 10.88 31.57 6.56 96,900 2.76 RURAL 111,378 57,558 53,820 - 106.95 6.04 69,094 2.54 URBAN 51,388 27,073 24,315 - 111.34 8.05 27,806 3.28 KHUZDAR DISTRICT 35,380 798,896 419,351 379,468 77 110.51 22.58 34.52 6.59 417,466 3.47 RURAL 523,134 274,438 248,631 65 110.38 6.36 299,218 2.98 URBAN 275,762 144,913 130,837 12 110.76 7.06 118,248 4.55 LASBELA DISTRICT 15,153 576,271 301,204 275,056 11 109.51 38.03 48.92 6.21 312,695 3.26 RURAL 294,373 153,099 141,271 3 108.37 5.46 197,271 2.13 URBAN 281,898 148,105 133,785 8 110.70 -

Updated Stratigraphy and Mineral Potential of Sulaiman Basin, Pakistan

Sindh Univ. Res. Jour. (Sci. Ser.) Vol.42 (2) 39-66 (2010) SURJ UPDATED STRATIGRAPHY AND MINERAL POTENTIAL OF SULAIMAN BASIN, PAKISTAN M. Sadiq Malkani Paleontology and Stratigraphy Branch, Geological Survey of Pakistan, Sariab Road, Quetta, Pakistan Abstract Sulaiman (Middle Indus) Basin represents Mesozoic and Cainozoic strata and have deposits of sedimentary minerals with radioactive and fuel minerals. The new coal deposits and showings, celestite, barite, fluorite, huge gypsum deposits, marble (limestone), silica sand, glauconitic and hematitic sandstone (iron and potash), clays, construction stone are being added here. Sulaiman Basin was previously ignored for updating of stratigraphy and economic mineral potential. Here most of known information on Sulaiman Basin is compiled and presented along with new economic deposits. Keywords: Stratigraphy, Mineral deposits, Sulaiman Basin, Middle Indus Basin, Pakistan. 1. Introduction metamorphic and sedimentary rocks. The study area is The Indus Basin which is a part of located in the central part of Pakistan (Fig.1a). Gondwanan lands (Southern Earth) is separated by an Previously, the Sulaiman Basin has received little Axial Belt (Suture Zone) from the Balochistan and attention, but this paper will add insights on updated Northern areas of Tethyan and Laurasian domains stratigraphy and new mineral discoveries. (northern earth). The Indus Basin (situated in the North-western part of Indo-Pakistan subcontinent) is 2. Materials and Methods located in the central and eastern part of Pakistan and The materials belong to collected field data, further subdivided in to upper (Kohat and Potwar), during many field seasons like lithology, structure, middle (Sulaiman) and Lower (Kirthar) basins. The stratigraphy and mineral commodities (Figs. -

Pakistan: the Worsening Conflict in Balochistan

PAKISTAN: THE WORSENING CONFLICT IN BALOCHISTAN Asia Report N°119 – 14 September 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. CENTRALISED RULE AND BALOCH RESISTANCE ............................................ 2 A. A TROUBLED HISTORY .........................................................................................................3 B. RETAINING THE MILITARY OPTION .......................................................................................4 C. A DEMOCRATIC INTERLUDE..................................................................................................6 III. BACK TO THE BEGINNING ...................................................................................... 7 A. CENTRALISED POWER ...........................................................................................................7 B. OUTBREAK AND DIRECTIONS OF CONFLICT...........................................................................8 C. POLITICAL ACTORS...............................................................................................................9 D. BALOCH MILITANTS ...........................................................................................................12 IV. BALOCH GRIEVANCES AND DEMANDS ............................................................ 13 A. POLITICAL AUTONOMY .......................................................................................................13 -

Buffer Zone, Colonial Enclave, Or Urban Hub?

Working Paper no. 69 - Cities and Fragile States - BUFFER ZONE, COLONIAL ENCLAVE OR URBAN HUB? QUETTA :BETWEEN FOUR REGIONS AND TWO WARS Haris Gazdar, Sobia Ahmad Kaker, Irfan Khan Collective for Social Science Research February 2010 Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) Copyright © H. Gazdar, S. Ahmad Kaker, I. Khan, 2010 24 Crisis States Working Paper Buffer Zone, Colonial Enclave or Urban Hub? Quetta: Between Four Regions and Two Wars Haris Gazdar, Sobia Ahmad Kaker and Irfan Khan Collective for Social Science Research, Karachi, Pakistan Quetta is a city with many identities. It is the provincial capital and the main urban centre of Balochistan, the largest but least populous of Pakistan’s four provinces. Since around 2003, Balochistan’s uneasy relationship with the federal state has been manifested in the form of an insurgency in the ethnic Baloch areas of the province. Within Balochistan, Quetta is the main shared space as well as a point of rivalry between the two dominant ethnic groups of the province: the Baloch and the Pashtun.1 Quite separately from the internal politics of Balochistan, Quetta has acquired global significance as an alleged logistic base for both sides in the war in Afghanistan. This paper seeks to examine different facets of Quetta – buffer zone, colonial enclave and urban hub − in order to understand the city’s significance for state building in Pakistan. State-building policy literature defines well functioning states as those that provide security for their citizens, protect property rights and provide public goods. States are also instruments of repression and the state-building process is often wrought with conflict and the violent suppression of rival ethnic and religious identities, and the imposition of extractive economic arrangements (Jones and Chandaran 2008).