Balochistan Conflict: Internal and International Dynamics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders (W/Out Cnic) As of December 31, 2017

ASKARI BANK LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS (W/OUT CNIC) AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2017 S. NO. FOLIO NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDERS ADDRESSES OF THE SHAREHOLDERS NO. OF SHARES 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN C/O BANK OF AMERICA, BLUE AREA, ISLAMABAD. 2878 12 68 MR. WASEEM AHMED HOUSE NO.485, STREET NO.17, CHAKLALA SCHEME-III, RAWALPINDI. 5945 13 71 MS. SHAMEEM QUAVI SIDDIQUI 112/1, 13TH STREET, PHASE-VI, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, KARACHI-75500. 2695 14 74 MS. YAZDANI BEGUM HOUSE NO.A-75, BLOCK-13, GULSHAN-E-IQBAL, KARACHI. -

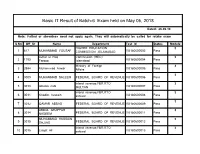

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam Held on May 05, 2018

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam S.No Off_Sr Name Department Test Id Status Module HIGHER EDUCATION 3 1 617 MUHAMMAD YOUSAF COMMISSION ,ISLAMABAD VU180600002 Pass Azhar ul Haq Commission (HEC) 3 2 1795 Farooq Islamabad VU180600004 Pass Ministry of Foreign 3 3 2994 Muhammad Anwar Affairs VU180600005 Pass 3 4 3009 MUHAMMAD SALEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600006 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 5 3010 Ghulan nabi MULTAN VU180600007 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 6 3011 Khadim hussain sahiwal VU180600008 Pass 3 7 3012 QAMAR ABBAS FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600009 Pass ABDUL GHAFFAR 3 8 3014 NADEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600011 Pass MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN 3 9 3015 SAJJAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600012 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 10 3016 Liaqat Ali sahiwal VU180600013 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 11 3017 Tariq javed sahiwal VU180600014 Pass 3 12 3018 AFTAB AHMAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600015 Pass Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Muhammad inam-ul- inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 13 3019 haq MULTAN VU180600016 Pass Ministry of Defense (Defense Division) 3 Rawalpindi. 14 4411 Asif Mehmood VU180600018 Pass 3 15 4631 Rooh ul Amin Pakistan Air Force VU180600022 Pass Finance/Income Tax 3 16 4634 Hammad Qureshi Department VU180600025 Pass Federal Board Of Revenue 3 17 4635 Arshad Ali Regional Tax-II VU180600026 Pass 3 18 4637 Muhammad Usman Federal Board Of Revenue VU180600027 -

23Rd Indian Infantry Division

21 July 2012 [23 INDIAN INFANTRY DIVISION (1943)] rd 23 Indian Infantry Division (1) st 1 Indian Infantry Brigade (2) 1st Bn. The Seaforth Highlanders (Ross-shire Buffs, The Duke of Albany’s) th th 7 Bn. 14 Punjab Regiment (3) 1st Patiala Infantry (Rajindra Sikhs), Indian State Forces st 1 Bn. The Assam Regiment (4) 37th Indian Infantry Brigade 3rd Bn. 3rd Queen Alexandra’s Own Gurkha Rifles 3rd Bn. 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles (Frontier Force) 3rd Bn. 10th Gurkha Rifles 49th Indian Infantry Brigade 4th Bn. 5th Mahratta Light Infantry 5th (Napiers) Bn. 6th Rajputana Rifles nd th 2 (Berar) Bn. 19 Hyderabad Regiment (5) Divisional Troops The Shere Regiment (6) The Kali Badahur Regiment (6) th 158 Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (7) 3rd Indian Field Regiment, Indian Artillery 28th Indian Mountain Regiment, Indian Artillery nd 2 Indian Anti-Tank Regiment, Indian Artillery (8) 68th Field Company, King George V’s Own Bengal Sappers and Miners 71st Field Company, King George V’s Own Bengal Sappers and Miners 91st Field Company, Royal Bombay Sappers and Miners 323rd Field Park Company, Queen Victoria’s Own Madras Sappers and Miners 23rd Indian Divisional Signals, Indian Signal Corps 24th Indian Field Ambulance, Indian Army Medical Corps 47th Indian Field Ambulance, Indian Army Medical Corps 49th Indian Field Ambulance, Indian Army Medical Corps © www.britishmilitaryhistory.co.uk Page 1 21 July 2012 [23 INDIAN INFANTRY DIVISION (1943)] NOTES: 1. The division was formed on 1st January 1942 at Jhansi in India. In March, the embryo formation moved to Ranchi where the majority of the units joined it. -

Pakistan's Army

Pakistan’s Army: New Chief, traditional institutional interests Introduction A year after speculation about the names of those in the race for selection as the new Army Chief of Pakistan began, General Qamar Bajwa eventually took charge as Pakistan's 16th Chief of Army Staff on 29th of November 2016, succeeding General Raheel Sharif. Ordinarily, such appointments in the defence services of countries do not generate much attention, but the opposite holds true for Pakistan. Why this is so is evident from the popular aphorism, "while every country has an army, the Pakistani Army has a country". In Pakistan, the army has a history of overshadowing political landscape - the democratically elected civilian government in reality has very limited authority or control over critical matters of national importance such as foreign policy and security. A historical background The military in Pakistan is not merely a human resource to guard the country against the enemy but has political wallop and opinions. To know more about the power that the army enjoys in Pakistan, it is necessary to examine the times when Pakistan came into existence in 1947. In 1947, both India and Pakistan were carved out of the British Empire. India became a democracy whereas Pakistan witnessed several military rulers and still continues to suffer from a severe civil- military imbalance even after 70 years of its birth. During India’s war of Independence, the British primarily recruited people from the Northwest of undivided India which post partition became Pakistan. It is noteworthy that the majority of the people recruited in the Pakistan Army during that period were from the Punjab martial races. -

18Cboes of Tbe Lpast.'

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-59-03-08 on 1 September 1932. Downloaded from G. A. Kempthorne 217 effect of albumin is rememberep.. 'l'hus, where a complete method of steam sterilization by downward displacement cannot be used, the method of first washing in hot water, and then leaving the utensils to stand in ' potassium permanganate 1 in 1000 solution is recommended. Irieffective methods of sterilization are dangerous, in that they give a false sense of security. A,considerable number of experiments were done in the Pat-hological Department of Trinity College, Dublin; and my thanks are due to Professor J. W. Bigger, who gave me the facilities for carrying them out, and for many helpful suggestions. I should also like to thank Dr. G. C. Dockery and Dr. L. L. Griffiths for their advice.. and help . 18cboes of tbe lPast.' THE SECOND AFGHAN WAR., 1878-1879. guest. Protected by copyright. By LIEUTENANT·COLONEL G. A. KEMPTHORNE, D.S.O., Royal Army Medical Corps (R.P.). THE immediate cause of the Afghan Wars ofl878-1880 was the reception of a Russian Mission at Kabul and the refusal of the AmiI', Shere Ali, to admit a British one. War was declared in November, 1878, when three columns crossed into Afghanistan by way of the Khyber, the Kuram Valley, and the Khojak Pass respectively. The first column consisted of 10,000 British and Indian troops under Sir Samuel Browne, forming a division; the Kuram force, under Sir Frederick Roberts, was 5,500 strong; Sir Donald Stewart, operating through Quetta, bad a division equal to tbe first. -

Buffer Zone, Colonial Enclave, Or Urban Hub?

Working Paper no. 69 - Cities and Fragile States - BUFFER ZONE, COLONIAL ENCLAVE OR URBAN HUB? QUETTA :BETWEEN FOUR REGIONS AND TWO WARS Haris Gazdar, Sobia Ahmad Kaker, Irfan Khan Collective for Social Science Research February 2010 Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) Copyright © H. Gazdar, S. Ahmad Kaker, I. Khan, 2010 24 Crisis States Working Paper Buffer Zone, Colonial Enclave or Urban Hub? Quetta: Between Four Regions and Two Wars Haris Gazdar, Sobia Ahmad Kaker and Irfan Khan Collective for Social Science Research, Karachi, Pakistan Quetta is a city with many identities. It is the provincial capital and the main urban centre of Balochistan, the largest but least populous of Pakistan’s four provinces. Since around 2003, Balochistan’s uneasy relationship with the federal state has been manifested in the form of an insurgency in the ethnic Baloch areas of the province. Within Balochistan, Quetta is the main shared space as well as a point of rivalry between the two dominant ethnic groups of the province: the Baloch and the Pashtun.1 Quite separately from the internal politics of Balochistan, Quetta has acquired global significance as an alleged logistic base for both sides in the war in Afghanistan. This paper seeks to examine different facets of Quetta – buffer zone, colonial enclave and urban hub − in order to understand the city’s significance for state building in Pakistan. State-building policy literature defines well functioning states as those that provide security for their citizens, protect property rights and provide public goods. States are also instruments of repression and the state-building process is often wrought with conflict and the violent suppression of rival ethnic and religious identities, and the imposition of extractive economic arrangements (Jones and Chandaran 2008). -

District Development B

District Development B o P R O F I L E l a n 2 0 1 1 - D i s t Kachhi r i c t D e v e l o p m e n t P r o f i l e 2 0 1 0 Planning & Development Department United Nations Children’s Fund Government of Balochistan, Quetta Provincial Office Balochistan, Quetta Planning & Development Department, Government of Balochistan in Collaboration with UNICEF District Development P R O F I L E 2 0 1 1 K a c h h i Prepared by Planning & Development Department, Government of Balochistan, Quetta in Collaboration with United Nations Children’s Fund Provincial Office Balochistan, Quetta July 18, 2011 Message Foreword In this age of knowledge economy, reliance on every possible tool The Balochistan District Development Profiles 2010 is a landmark exercise of Planning and available for decision making is crucial for improving public resource Development Department, Government of Balochistan, to update the district profile data management, brining parity in resource distribution and maximizing that was first compiled in 1998. The profiles have been updated to provide a concise impact of development interventions. These District Development landmark intended for development planning, monitoring and management purposes. Profiles are vivid views of Balochistan in key development areas. The These districts profiles would be serving as a tool for experts, development practitioners Planning and Development Department, Government of Balochistan and decision-makers/specialists by giving them vast information wrapping more than 18 is highly thankful to UNICEF Balochistan for the technical and dimensions from Balochistans' advancement extent. -

Physical Geography of the Punjab

19 Gosal: Physical Geography of Punjab Physical Geography of the Punjab G. S. Gosal Formerly Professor of Geography, Punjab University, Chandigarh ________________________________________________________________ Located in the northwestern part of the Indian sub-continent, the Punjab served as a bridge between the east, the middle east, and central Asia assigning it considerable regional importance. The region is enclosed between the Himalayas in the north and the Rajputana desert in the south, and its rich alluvial plain is composed of silt deposited by the rivers - Satluj, Beas, Ravi, Chanab and Jhelam. The paper provides a detailed description of Punjab’s physical landscape and its general climatic conditions which created its history and culture and made it the bread basket of the subcontinent. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Herodotus, an ancient Greek scholar, who lived from 484 BCE to 425 BCE, was often referred to as the ‘father of history’, the ‘father of ethnography’, and a great scholar of geography of his time. Some 2500 years ago he made a classic statement: ‘All history should be studied geographically, and all geography historically’. In this statement Herodotus was essentially emphasizing the inseparability of time and space, and a close relationship between history and geography. After all, historical events do not take place in the air, their base is always the earth. For a proper understanding of history, therefore, the base, that is the earth, must be known closely. The physical earth and the man living on it in their full, multi-dimensional relationships constitute the reality of the earth. There is no doubt that human ingenuity, innovations, technological capabilities, and aspirations are very potent factors in shaping and reshaping places and regions, as also in giving rise to new events, but the physical environmental base has its own role to play. -

Comparing Camels in Afghanistan and Australia: Industry and Nationalism During the Long Nineteenth Century

Comparing camels in Afghanistan and Australia: Industry and nationalism during the Long Nineteenth Century Shah Mahmoud Hanifi [James Madison University, Virginia, USA] Abstract: This paper compares the roles of camels and their handlers in state building projects in Afghanistan and Australia during the global ascendance of industrial production. Beginning in the mid-1880s the Afghan state-sponsored industrial project known as the mashin khana or Kabul workshops had significant consequences for camel-based commercial transport in and between Afghanistan and colonial India. Primary effects include the carriage of new commodities, new forms of financing and taxation, re- routing, and markedly increased state surveillance over camel caravans. In Australia the trans-continental railway and telegraph, and other projects involving intra-continental exploration and mining, generated a series of in-migrations of Afghan camels and cameleers between the 1830s and 1890s. The port of Adelaide was the urban center most affected by Afghan camels and cameleers, and a set of new interior markets and settlements originate from these in-migrations. The contributions of Afghan camels and their handlers to state-building projects in nineteenth-century Afghanistan and Australia highlight their vital roles in helping to establish industrial enterprises, and the equally important point that once operational these industrial projects became agents in the economic marginalization of camels and the social stigmatization of the human labour associated with them. __________________________________________________________________ Introduction: camels, political economy and national identities The movement of camels through the Hindu Kush mountain passes was greatly transformed beginning in 1893. That year the Durrani Amir of Kabul Abd al-Rahman signed an agreement with the British Indian colonial official Sir Henry Mortimer Durand acknowledging there would be formal demarcation of the border between their respective vastly unequal powers, one being a patron and the other a client. -

Ancient Regions, New Frontier the Prehistory of the Durand Line in Baluchistan

Internationales Asienforum, Vol. 44 (2013), No. 1–2, pp. 7–24 Ancient Regions, New Frontier The Prehistory of the Durand Line in Baluchistan JAKOB RÖSEL* Abstract The prehistory of the Durand Line is complicated, involving new forms of tribal al- legiance-building, tribal and localised state-building and, finally, regional empire- building. A new tribal as well as mercantile religion and civilisation, Islam, gave rise to new patterns of trade and a new crossroads and commercial centre: Kalat. With the decline of the Mughals a Kalat state based on a local dynasty and two tribal fed- erations emerged as a semi-independent state. The British Empire ultimately strength- ened and enlarged, balanced and controlled this tribal and regional state. Thanks to the British the Khan of Kalat controlled most of present-day Baluchistan. From the 1870s the construction of this imperial state served new geostrategic designs: the Khan of Kalat conceded control over the Bolan Pass as well as Quetta to the British Empire. It was this imperial bridgehead, called British Baluchistan, which served as the cornerstone for a forward border policy and, ultimately, the Durand Line. Keywords Frontiers, imperialism, British India, Baluchistan, Durand Line Introduction A frontier, border or boundary can have various forms and functions. The actual artefact is only the empirical, spatial manifestation of versatile social or political, cultural or economic intentions, designs or strategies. Borders serve an offensive or defensive function. They are inclusive or exclusive. They can operate as the exoskeleton of an emerging state. They can either create or fail to create and demarcate ethnic loyalties or political identities. -

Mehrgarh Neolithic

Paper presented in the International Seminar on the "First Farmers in Global Perspective', Lucknow, India, 18-20 January, 2006 Mehrgarh Neolithic Jean-Fran¸ois Jarrige From 1975 to 1985, the French Archaeological had already provided a summary of the main results Mission, in collaboration with the Department of brought by the excavations conducted from 1977 Archaeology of Pakistan, has conducted excavations to 1985 in the Neolithic sector of Mehrgarh. in a wide archaeological area near to the modern From 1985 to 1996, the excavations at Mehrgarh village of Mehrgarh in Balochistan at the foot of the were stopped and the French Mission undertook the Bolan Pass, one of the major communication routes excavation of a mound close to the village of between the Iranian Plateau, Central Asia and the Nausharo, 6 miles South of Mehrgarh. This excavation Indus Valley. showed clearly that the mound of Nausharo had Mehrgarh is located in the Bolan Basin, in the north- been occupied from 3000 to 2000 BC. After a western part of the Kachi-Bolan plain, a great alluvial Period I contemporary with Mehrgarh VI and VII, expanse that merges with the Indus Valley (Fig. 1). Periods II and III (c. 2500 to 2000 BC) at Nausharo The site itself is a vast area of about 300 hectares belong to the Indus (or Harappan) civilisation. covered with archaeological remains left by a Therefore the excavations at Nausharo allowed us to continuous sequence of occupations from the 8th to link in the Kachi-Bolan region, the Indus civilisation the 3rd millennium BC. to a continuous sequence of occupations starting from the aceramic Neolithic period. -

Lithofacies, Depositional Environments, and Regional Stratigraphy of the Lower Eocene Ghazij Formation, Balochistan, Pakistan

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Lithofacies, Depositional Environments, and Regional Stratigraphy of the Lower Eocene Ghazij Formation, Balochistan, Pakistan U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1599 Prepared in cooperation with the Geological Survey of Pakistan A Cover. Exposures of the lower Eocene Ghazij Formation along the northeast flank of the Sor Range, Balochistan, Pakistan. Photograph by Stephen B. Roberts. Lithofacies, Depositional Environments, and Regional Stratigraphy of the Lower Eocene Ghazij Formation, Balochistan, Pakistan By Edward A. Johnson, Peter D. Warwick, Stephen B. Roberts, and Intizar H. Khan U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1599 Prepared in cooperation with the Geological Survey of Pakistan UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1999 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Information Services Box 25286, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lithofacies, depositional environments, and regional stratigraphy of the lower Eocene Ghazij Formation, Balochistan, Pakistan / by Edward A. Johnson . .[et al.]. p. cm.—(U.S. Geological Survey professional paper ; 1599) "Prepared in cooperation with the Geological Survey of Pakistan." Includes bibliographical references. 1. Geology, Stratigraphic—Eocene. 2. Geology—Pakistan— Balochistan. 3. Coal—Geology—Pakistan—Balochistan. 4. Ghazij Formation (Pakistan). I. Johnson, Edward A. (Edward Allison), 1940- . II. Series. QE692.2.L58 1999 553.2'4'0954915—dc21 98-3305 ISBN=0-607-89365-6 CIP CONTENTS Abstract..........................................................................................................................