Physical Geography of the Punjab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTRODUCTION the Total Coast Line of Pakistan Is About 1120 Km The

INTRODUCTION The total coast line of Pakistan is about 1120 Km the western region (Makran coast) extends from Hub river to Iranian border. Makran coast is about 772 Km long. The South Eastern Region (Sindh coast) extends from Hub River to Sir Creek on the Indian border and is about 348 Km long. The continental shelf of Makran coast lies between 16 to 24 Km and falls sharply to great depths. Whereas, in Sindh coast the continental shelf is shallow and is about 125 Km. According to constitution of Pakistan, the marine waters are divided into the administrative areas: (i) Territorial waters (from base line upto 12 nautical miles, seaward). These waters have jurisdiction of the maritime provinces of Sindh and Balochistan. (ii) The waters between 12 nautical miles and 200 nautical miles: the Federal Government has jurisdiction on this area. Pakistan has rich marine resources in its coastal areas. Since ages, fishing has been the main livelihood of the coastal fishermen. Although, rapid changes have taken place in the world fisheries by introducing modern sophisticated fishing vessels and gear. However, the marine fisheries of Pakistan is still in primitive stage. The local small scales wooden fishing boats are not capable to harvest deep water resources. As such, deep water area remained un-exploited. Therefore, in the past a limited licenses were given to the local parties allowing them to undertake joint venture with foreign parties to harvest tuna & tuna like species in EEZ of Pakistan beyond 35 nautical miles. The operation of these vessels was subject to fulfillment of provision of Deep Sea Fishing Policy including strict surveillance and monitoring by Marine Fisheries Department (MFD), Maritime Security Agency (MSA), port inspections, installation of vessel-based unit of Vessel Monitoring System (VMS), MFD representative / observer on each vessel during each trip, restriction on discard of fish at sea, having penalties on violation of regulations etc. -

Visualizing Hydropower Across the Himalayas: Mapping in a Time of Regulatory Decline

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 34 Number 2 Article 9 December 2014 Visualizing Hydropower Across the Himalayas: Mapping in a time of Regulatory Decline Kelly D. Alley Auburn University, [email protected] Ryan Hile University of Utah Chandana Mitra Auburn University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Alley, Kelly D.; Hile, Ryan; and Mitra, Chandana. 2014. Visualizing Hydropower Across the Himalayas: Mapping in a time of Regulatory Decline. HIMALAYA 34(2). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol34/iss2/9 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Visualizing Hydropower Across the Himalayas: Mapping in a time of Regulatory Decline Acknowledgements Earlier drafts of this paper were presented at the BAPA-BEN International Conference on Water Resources in Dhaka, Bangladesh in 2013 and for the AAA panel on Developing the Himalaya in 2012. The authors appreciate the comments and support provided by members who attended these sessions. Our mapping project has been supported by the College of Liberal Arts and the Center for Forest Sustainability at Auburn University. This research article is available in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol34/iss2/9 Visualizing Hydropower across the Himalayas: Mapping in a time of Regulatory Decline Kelly D. -

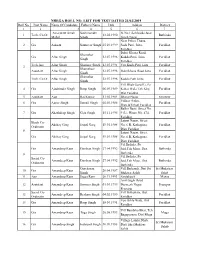

NREGA ROLL NO. LIST for TEST DATED 21/02/2019 Roll No

NREGA ROLL NO. LIST FOR TEST DATED 21/02/2019 Roll No. Post Name Name Of Candidate Father's Name Dob Address District 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Amarpreet Singh Sukhmander St.No.1,Sahibjada Jujar 1 Tech. Co.Or. 13.02.1990 Bathinda Mahal Singh Singh Nagar Near Police Thana, 2 Grs Aakash Sukhveer Singh 25.10.1999 Sada Patti, Jaito, Faridkot Faridkot Dabri Khana Road, Shemsher Grs Aftar Singh 12.07.1996 Kuddo Patti, Jaito, Faridkot Singh Faridkot Tech.Ass. Aftar Singh Shamser Singh 12.07.1996 Vpo Kudo Patti Jaitu Faridkot 3 Shamsheer Assistant Aftar Singh 12.07.1996 Dabrikhana Road Jaitu Faridkot Singh Shamsher Tech. Co.Or. Aftar Singh 12.07.1996 Kaddo Patti Jaito Faridkot Singh Vill Dhab Guru Ki, Po 4 Grs Ajadvinder Singh Roop Singh 06.09.1989 Kohar Wala Teh:Kkp, Faridkot Dist Faridkot 5 Assistant Ajay Raj Kumar 13.02.1989 Bharat Nagar, Ferozpur Village Sadiq, 6 Grs Ajmer Singh Jarnail Singh 05.03.1988 Faridkot Distt.&Tehsel Faridkot Balbir Basti, Street No. 7 Grs Akashdeep Singh Geja Singh 15.11.1995 9 (L), House No. 474, Faridkot Faridkot Lajpat Nagar, Street Block Co- Akshay Garg Jaipal Garg 19.01.1988 No. 6 B, Kotkapura, Faridkot Ordinator 8 Distt Faridkot Lajpat Nagar, Street Grs Akshay Garg Jaipal Garg 19.01.1988 No. 6 B, Kotkapura, Faridkot Distt Faridkot Vil Badiala, Po Grs Amandeep Kaur Darshan Singh 27.04.1992 Jaid,Teh Mour, Dist Bathinda 9 Bathinda Vil Badiala, Po Social Co- Amandeep Kaur Darshan Singh 27.04.1992 Jaid,Teh Mour, Dist Bathinda Ordinator Bathinda Gurcharan Vill Barkandi, Dist Sri Sri Mukatsar 10 Grs Amandeep Kaur 20.04.1987 -

EXPLORATIONS in KECH-MAKRAN and EXCAVATIONS at MIRI QALAT Aurore Didier, David Sarmiento Castillo

EXPLORATIONS IN KECH-MAKRAN AND EXCAVATIONS AT MIRI QALAT Aurore Didier, David Sarmiento Castillo To cite this version: Aurore Didier, David Sarmiento Castillo. EXPLORATIONS IN KECH-MAKRAN AND EXCAVA- TIONS AT MIRI QALAT: MAFM Mission, direction: Roland Besenval Cooperation: Department of Archaeology and Museums of Pakistan. International Seminar on ”French Contributions to Pakistan Studies”, Feb 2014, Islamabad; Karachi; Banbhore, Pakistan. 2014. halshs-02986870 HAL Id: halshs-02986870 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02986870 Submitted on 3 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. EXPLORATIONS IN KECH-MAKRAN AND EXCAVATIONS AT MIRI QALAT 5 MAFM Mission, direction: Roland Besenval Cooperation: Department of Archaeology and Museums of Pakistan EXTENSIVE SURVEYS AND EXPLORATIONS (1986-1990 / 1990-2006) Dr. Roland Besenval. Founder of the French Archaeological 228 archaeological sites were inventoried by the MAFM Mission during an extensive survey Mission in Makran (Balochistan) and exploration program conducted in Kech-Makran (southwestern Balochistan). Th eir that he directed from 1986 to dating was defi ned from the study of collections of surface potsherds. Some areas of Makran 2012. Attached to the French currently very little inhabited, have shown the remains of an important occupation during National Center for Scientifi c the protohistoric period, particularly in the Dasht plain where dozens of 3rd millennium Research (CNRS), he conducted sites were discovered. -

Mississippi Alluvial Plain

Mississippi Alluvial Plain Physical description This riverine ecoregion extends along the Mississippi River, south to the Gulf of Mexico. It is mostly a flat, broad floodplain with river terraces and levees providing the main elements of relief. Soils tend to be poorly drained, except for the areas of sandy soils. Locations with deep, fertile soils are sometimes extremely dense and poorly drained. The combination of flat terrain and poor drainage creates conditions suitable for wetlands. Bottomland deciduous forest vegetation covered the region before much of it was cleared for cultivation. Winters are mild and summers are hot. The wetlands of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain are an internationally important winter habitat for migratory waterfowl. The White River National Wildlife Refuge alone offers migration habitat to upwards of 10,000 Canada geese and 300,000 ducks every year. These large numbers account for one-third of the total found in Arkansas, and 10% of the waterfowl found in the Mississippi Flyway. At one time, wetlands were very abundant across the Mississippi Alluvial Plain. The decline in wetlands began several centuries ago when the first ditches were dug to drain extensive areas. Clearing bottomland hardwood forests for agriculture and other activities resulted in the loss of more than 70% of the original wetlands. Presently, most of the ecoregion is agricultural, cleared of natural vegetation and drained by a system of ditches. Dominant vegetation On the Mississippi Alluvial Plain, changes in elevation of only a few inches can result in great differences in soil saturation characteristics, and therefore the species of plants that thrive. -

Kangra, Himachal Pradesh

` SURVEY DOCUMENT STUDY ON THE DRAINAGE SYSTEM, MINERAL POTENTIAL AND FEASIBILITY OF MINING IN RIVER/ STREAM BEDS OF DISTRICT KANGRA, HIMACHAL PRADESH. Prepared By: Atul Kumar Sharma. Asstt. Geologist. Geological Wing” Directorate of Industries Udyog Bhawan, Bemloe, Shimla. “ STUDY ON THE DRAINAGE SYSTEM, MINERAL POTENTIAL AND FEASIBILITY OF MINING IN RIVER/ STREAM BEDS OF DISTRICT KANGRA, HIMACHAL PRADESH. 1) INTRODUCTION: In pursuance of point 9.2 (Strategy 2) of “River/Stream Bed Mining Policy Guidelines for the State of Himachal Pradesh, 2004” was framed and notiofied vide notification No.- Ind-II (E)2-1/2001 dated 28.2.2004 and subsequently new mineral policy 2013 has been framed. Now the Minstry of Environemnt, Forest and Climate Change, Govt. of India vide notifications dated 15.1.2016, caluse 7(iii) pertains to preparation of Distt Survey report for sand mining or riverbed mining and mining of other minor minerals for regulation and control of mining operation, a survey document of existing River/Stream bed mining in each district is to be undertaken. In the said policy guidelines, it was provided that District level river/stream bed mining action plan shall be based on a survey document of the existing river/stream bed mining in each district and also to assess its direct and indirect benefits and identification of the potential threats to the individual rivers/streams in the State. This survey shall contain:- a) District wise detail of Rivers/Streams/Khallas; and b) District wise details of existing mining leases/ contracts in river/stream/khalla beds Based on this survey, the action plan shall divide the rivers/stream of the State into the following two categories;- a) Rivers/ Streams or the River/Stream sections selected for extraction of minor minerals b) Rivers/ Streams or the River/Stream sections prohibited for extraction of minor minerals. -

Most Important Mcqs (Set III) for CSS, PMS, PCS, NTS

Pakistan Studies/Affairs: Most Important MCQs (Set III) for CSS, PMS, PCS, NTS Jinnah Barrage is located near: (a) Kalabagh (b) Tarbela Dam (c) Warsak Dam (d) None of these Answer: a The largest desert of Pakistan is: (a) Thal (b) Thar (c) Sehan (d) Cholistan Answer: b The total height of Peshawar from sea level is: (a) 1160 ft (b) 1164 ft (c) 1164 ft (d) 1178 ft Answer: b How high is Quetta from sea level? (a) 5000 ft (b) 5500 ft (c) 6000 ft Answer: b Taunsa Barrage was completed in: (a) 1953 (b) 1955 (c) 1956 (d) 1958 Answer: d Check Also: Important and Most Wanted MCQs about Current Federal Cabinet of Pakistan Sindh Sagar Doab is between the rivers of: (a) Indus and Jhelum Downloaded from www.csstimes.pk | 1 Pakistan Studies/Affairs: Most Important MCQs (Set III) for CSS, PMS, PCS, NTS (b) Indus and Chenab (c) Sutluj and Ravi (d) Ravi and Chenab Answer: a Ganji Bar is between the rivers of: (a) Ravi and Chenab (b) Ravi and Satluj (c) Jhelum and Chenab (d) Indus and Jhelum Answer: b The city has maximum height from sea level is: (a) Ziarat (b) Murree (c) Khanpur (d) Loralai Answer: b Chaj Doab is located between the rivers: (a) Ravi and Chenab (b) Jhelum and Chenab (c) Indus and Ravi (d) Ravi and Jhelum Answer: b Jinnah Barrage was completed in: (a) 1970 (b) 1946 (c) 1965 (d) None of these Answer: b The first canal built by British in the subcontinent is: (a) Sohag Canal (b) Upper Bari Doab (c) Chenab Canal (d) Lower Bari Doab Answer: b Downloaded from www.csstimes.pk | 2 Pakistan Studies/Affairs: Most Important MCQs (Set III) for CSS, -

How Geography "Mapped" East Asia, Part One: China by Craig Benjamin, Big History Project, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 01.26.17 Word Count 1,354 Level 1020L

How Geography "Mapped" East Asia, Part One: China By Craig Benjamin, Big History Project, adapted by Newsela staff on 01.26.17 Word Count 1,354 Level 1020L TOP: The Stalagmite Gang peaks at the East Sea area of Huangshan mountain in China. Photo by: Education Images/UIG via Getty Images MIDDLE: Crescent Moon Lake and oasis in the middle of the desert. Photo by: Tom Thai, Flickr. BOTTOM: Hukou Waterfall in the Yellow River. Photo by: Wikimedia The first in a two-part series In what ways did geography allow for the establishment of villages and towns — some of which grew into cities — in various regions of East Asia? What role did climate play in enabling powerful states and civilizations to appear in some areas while other locations remained better suited for a nomadic lifestyle? Let's begin to answer these questions with a story about floods in China. China's two great rivers — the Yangtze and the Yellow — have flooded regularly for as long as we can measure in the historical and geological record. Catastrophic floodwaters This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. Nothing can compare, though, to the catastrophic floods of August 19, 1931. The Yangtze river rose an astonishing 53 feet above its normal level in just one day. It unleashed some of the most destructive floodwaters ever seen. The floods were caused by a "perfect storm" of conditions. Monsoon rains, heavy snowmelt, and unexpected rains pounded huge areas of southern China. All this water poured into the Yangtze. The river rose and burst its banks for hundreds of miles. -

Pdf 325,34 Kb

(Final Report) An analysis of lessons learnt and best practices, a review of selected biodiversity conservation and NRM projects from the mountain valleys of northern Pakistan. Faiz Ali Khan February, 2013 Contents About the report i Executive Summary ii Acronyms vi SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. The province 1 1.2 Overview of Natural Resources in KP Province 1 1.3. Threats to biodiversity 4 SECTION 2. SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS (review of related projects) 5 2.1 Mountain Areas Conservancy Project 5 2.2 Pakistan Wetland Program 6 2.3 Improving Governance and Livelihoods through Natural Resource Management: Community-Based Management in Gilgit-Baltistan 7 2.4. Conservation of Habitats and Species of Global Significance in Arid and Semiarid Ecosystem of Baluchistan 7 2.5. Program for Mountain Areas Conservation 8 2.6 Value chain development of medicinal and aromatic plants, (HDOD), Malakand 9 2.7 Value Chain Development of Medicinal and Aromatic plants (NARSP), Swat 9 2.8 Kalam Integrated Development Project (KIDP), Swat 9 2.9 Siran Forest Development Project (SFDP), KP Province 10 2.10 Agha Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) 10 2.11 Malakand Social Forestry Project (MSFP), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 11 2.12 Sarhad Rural Support Program (SRSP) 11 2.13 PATA Project (An Integrated Approach to Agriculture Development) 12 SECTION 3. MAJOR LESSONS LEARNT 13 3.1 Social mobilization and awareness 13 3.2 Use of traditional practises in Awareness programs 13 3.3 Spill-over effects 13 3.4 Conflicts Resolution 14 3.5 Flexibility and organizational approach 14 3.6 Empowerment 14 3.7 Consistency 14 3.8 Gender 14 3.9. -

Administrative Atlas , Punjab

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 PUNJAB ADMINISTRATIVE ATLAS f~.·~'\"'~ " ~ ..... ~ ~ - +, ~... 1/, 0\ \ ~ PE OPLE ORIENTED DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, PUNJAB , The maps included in this publication are based upon SUNey of India map with the permission of the SUNeyor General of India. The territorial waters of India extend into the sea to a distance of twelve nautical miles measured from the appropriate base line. The interstate boundaries between Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Meghalaya shown in this publication are as interpreted from the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971 but have yet to be verified. The state boundaries between Uttaranchal & Uttar Pradesh, Bihar & Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh & Madhya Pradesh have not been verified by government concerned. © Government of India, Copyright 2006. Data Product Number 03-010-2001 - Cen-Atlas (ii) FOREWORD "Few people realize, much less appreciate, that apart from Survey of India and Geological Survey, the Census of India has been perhaps the largest single producer of maps of the Indian sub-continent" - this is an observation made by Dr. Ashok Mitra, an illustrious Census Commissioner of India in 1961. The statement sums up the contribution of Census Organisation which has been working in the field of mapping in the country. The Census Commissionarate of India has been working in the field of cartography and mapping since 1872. A major shift was witnessed during Census 1961 when the office had got a permanent footing. For the first time, the census maps were published in the form of 'Census Atlases' in the decade 1961-71. Alongwith the national volume, atlases of states and union territories were also published. -

The Geographic, Geological and Oceanographic Setting of the Indus River

16 The Geographic, Geological and Oceanographic Setting of the Indus River Asif Inam1, Peter D. Clift2, Liviu Giosan3, Ali Rashid Tabrez1, Muhammad Tahir4, Muhammad Moazam Rabbani1 and Muhammad Danish1 1National Institute of Oceanography, ST. 47 Clifton Block 1, Karachi, Pakistan 2School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB24 3UE, UK 3Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA 4Fugro Geodetic Limited, 28-B, KDA Scheme #1, Karachi 75350, Pakistan 16.1 INTRODUCTION glaciers (Tarar, 1982). The Indus, Jhelum and Chenab Rivers are the major sources of water for the Indus Basin The 3000 km long Indus is one of the world’s larger rivers Irrigation System (IBIS). that has exerted a long lasting fascination on scholars Seasonal and annual river fl ows both are highly variable since Alexander the Great’s expedition in the region in (Ahmad, 1993; Asianics, 2000). Annual peak fl ow occurs 325 BC. The discovery of an early advanced civilization between June and late September, during the southwest in the Indus Valley (Meadows and Meadows, 1999 and monsoon. The high fl ows of the summer monsoon are references therein) further increased this interest in the augmented by snowmelt in the north that also conveys a history of the river. Its source lies in Tibet, close to sacred large volume of sediment from the mountains. Mount Kailas and part of its upper course runs through The 970 000 km2 drainage basin of the Indus ranks the India, but its channel and drainage basin are mostly in twelfth largest in the world. Its 30 000 km2 delta ranks Pakiistan. -

Ecoregions of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain

92° 91° 90° 89° 88° Ecoregions of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain Cape Girardeau 73cc 72 io Ri Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and quantity of This level III and IV ecoregion map was compiled at a scale of 1:250,000 and depicts revisions and Literature Cited: PRINCIPAL AUTHORS: Shannen S. Chapman (Dynamac Corporation), Oh ver environmental resources; they are designed to serve as a spatial framework for the research, subdivisions of earlier level III ecoregions that were originally compiled at a smaller scale (USEPA Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., eds., 1994, Omernik, J.M., 1987, Ecoregions of the conterminous United States (map Barbara A. Kleiss (USACE, ERDC -Waterways Experiment Station), James M. ILLINOIS assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and ecosystem components. By recognizing 2003, Omernik, 1987). This poster is part of a collaborative effort primarily between USEPA Region Ecoregions and subregions of the United States (map) (supplementary supplement): Annals of the Association of American Geographers, v. 77, no. 1, Omernik, (USEPA, retired), Thomas L. Foti (Arkansas Natural Heritage p. 118-125, scale 1:7,500,000. 71 the spatial differences in the capacities and potentials of ecosystems, ecoregions stratify the VII, USEPA National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory (Corvallis, Oregon), table of map unit descriptions compiled and edited by McNab, W.H., and Commission), and Elizabeth O. Murray (Arkansas Multi-Agency Wetland Bailey, R.G.): Washington, D.C., U.S. Department of Agriculture - Forest Planning Team). 37° environment by its probable response to disturbance (Bryce and others, 1999).