6 Accelerator Darlings, Challenges, and Future Plans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Map of Funding Sources for EU XR Technologies

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement N° 825545. XR4ALL (Grant Agreement 825545) “eXtended Reality for All” Coordination and Support Action D5.1: Map of funding sources for XR technologies Issued by: LucidWeb Issue date: 30/08/2019 Due date: 31/08/2019 Work Package Leader: Europe Unlimited Start date of project: 01 December 2018 Duration: 30 months Document History Version Date Changes 0.1 05/08/2019 First draft 0.2 26/08/2019 First version submitted for partners review 1.0 30/08/2019 Final version incorporating partners input Dissemination Level PU Public Restricted to other programme participants (including the EC PP Services) Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the EC RE Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the EC) This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement N° 825545. Main authors Name Organisation Leen Segers, Diana del Olmo LCWB Quality reviewers Name Organisation Youssef Sabbah, Tanja Baltus EUN Jacques Verly, Alain Gallez I3D LEGAL NOTICE The information and views set out in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. © XR4ALL Consortium, 2019 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. D5.1 Map of funding sources for XR technologies - 30/08/2019 Page 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ -

Tech Startup Ecosystem in West Bank and Gaza

Tech Startup Ecosystem in Public Disclosure Authorized West Bank and Gaza FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized This map was designed over a map produced by the Map Design Unit of the World Bank. The boundaries, colors, denominations and any other information shown on this map do not imply, on the part of The World Bank Group, any judgment on the legal status of any territory, or any endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Content Authors and Acknowledgements 1 Executive Summary 2 Measuring and Analyzing the Tech Startup Ecosystem in the West Bank and Gaza 5 Measuring the Tech Startup Ecosystem 5 Analyzing the Tech Startup Ecosystem 6 The Tech Startup Ecosystem in the West Bank and Gaza 9 Skills 12 Supporting Infrastructure for Entrepreneurship 14 Investment 17 Community 20 Startup Success Factors 23 Gap Analysis and Policy Recommendations 24 Summary of Gap Analysis and Stage of Ecosystem 24 Policy Recommendations 25 Appendix: Survey Methodology and Analysis 28 Methodology 28 Short-Term Success 32 Long-Term Success 32 Notes 33 References 34 LIST OF TABLES Table 1.1 Networking Assets 7 Table 1.2 Categories of Ecosystems 8 Table 3.1 Development Stage of Ecosystem 24 Table 3.2 Policy Recommendations 25 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 2.1: Startup Growth in the West Bank and Gaza 9 Figure 2.2: Time to Complete Procedural Tasks in Life Cycle of a Startup Across Regions 10 Figure 2.3: Percentage of Female Founders Across Analyzed Ecosystems 10 Figure 2.4: Gender Distribution -

The Bay Area Innovation System Science and the Impact of Public Investment

The Bay Area Innovation System Science and the Impact of Public Investment March 2019 Acknowledgments This report was prepared for the Bay Area Science and Jamie Lawrence, IBM Corporate Citizenship Manager – Innovation Consortium (BASIC) by Dr. Sean Randolph, California, Hawaii, Nevada, Utah, Washington Senior Director at the Bay Area Council Economic Daniel Lockney, Program Executive – Technology Transfer, Institute. Valuable assistance was provided by Dr. Dorothy NASA Miller, former Deputy Director of Innovation Alliances at Dr. Daniel Lowenstein, Executive Vice Chancellor and the University of California Office of the President and Provost, University of California San Francisco Naman Trivedi, a consultant to the Institute. Additional Dr. Kaspar Mossman, Director of Communications and support was provided by Estevan Lopez and Isabel Marketing, QB3 Monteleone, Research Analysts at the Institute. Dr. Patricia Olson, VP for Discovery & Translation, California Institute for Regenerative Medicine In addition to the members of BASIC’s board of Vanessa Sigurdson, Partnership Development, Autodesk directors, which provided review and commentary throughout the research process, the Economic Institute Dr. Aaron Tremaine, Department Head, Accelerator Technology Research, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory particularly wishes to thank the following individuals whose expertise, input and advice made valuable Eric Verdin, President & CEO, Buck Institute for Research on Aging contributions to the analaysis: Dr. Jeffrey Welser, Vice President & Lab Director, IBM Dr. Arthur Bienenstock, Special Assistant to the President for Research – Almaden Federal Policy, Stanford University Jim Brase, Deputy Associate Director for Programs, Computation Directorate, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory About BASIC Tim Brown, CEO, IDEO BASIC is the science and technology affiliate of the Doug Crawford, Managing Director, Mission Bay Capital Bay Area Council and the Bay Area Council Economic Dr. -

STARTUP ACCELERATOR PROGRAMMES a Practice Guide Acknowledgements

STARTUP ACCELERATOR PROGRAMMES A Practice Guide Acknowledgements This guide was produced by the Innovation Skills team in collaboration with the Policy and Research team. It draws on Nesta’s reports – specificallyThe Startup Factories written by Kirsten Bound and Paul Miller, and Good Incubation written by Jessica Stacey and Paul Miller – as well as Nesta’s practical experience supporting the startup and accelerator community in Europe. Thanks to Kate Walters, Jessica Stacey, Christopher Haley and Isobel Roberts, who all contributed to the content, and to Kirsten Bound, Brenton Caffin, Bas Leurs, Theo Keane, Sara Rizk and Simon Morrison who all provided valuable feedback along the way. Nesta’s Practice Guides This guide is part of a series of Practice Guides developed by Nesta’s Innovation Skills team. The guides have been designed to help you to learn about innovation methods and approaches and put them into practice in your work. For further information, contact [email protected] Nesta is an innovation charity with a mission to help people and organisations bring great ideas to life. We are dedicated to supporting ideas that can help improve all our lives, with activities ranging from early–stage investment to in–depth research and practical programmes. Nesta is a registered charity in England and Wales with company number 7706036 and charity number 1144091. Registered as a charity in Scotland number SCO42833. Registered office: 1 Plough Place, London, EC4A 1DE. www.nesta.org.uk ©Nesta 2014 STARTUP ACCELERATOR PROGRAMMES A Practice Guide CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 SECTION A: WHAT IS AN ACCELERATOR PROGRAMME? 6 SECTION B: WHY CONSIDER AN ACCELERATOR PROGRAMME? 12 SECTION C: SETTING UP AND RUNNING AN ACCELERATOR PROGRAMME 15 1. -

The Startup Factories. the Rise of Accelerator Programmes

Discussion paper: June 2011 The Startup Factories The rise of accelerator programmes to support new technology ventures Paul Miller and Kirsten Bound NESTA is the UK’s foremost independent expert on how innovation can solve some of the country’s major economic and social challenges. Its work is enabled by an endowment, funded by the National Lottery, and it operates at no cost to the government or taxpayer. NESTA is a world leader in its field and carries out its work through a blend of experimental programmes, analytical research and investment in early- stage companies. www.nesta.org.uk Executive summary Over the past six years, a new method of incubating technology startups has emerged, driven by investors and successful tech entrepreneurs: the accelerator programme. Despite growing interest in the model from the investment, business education and policy communities, there have been few attempts at formal analysis.1 This report is a first step towards a more informed critique of the phenomenon, as part of a broader effort among both public and private sectors to understand how to better support the growth of innovative startups. The accelerator programme model comprises five main features. The combination of these sets it apart from other approaches to investment or business incubation: • An application process that is open to all, yet highly competitive. • Provision of pre-seed investment, usually in exchange for equity. • A focus on small teams not individual founders. • Time-limited support comprising programmed events and intensive mentoring. • Cohorts or ‘classes’ of startups rather than individual companies. The number of accelerator programmes has grown rapidly in the US over the past few years and there are signs that more recently, the trend is being replicated in Europe. -

SILICON VALLEY Playbook

© 2017 | The official magazine for Published by the Consulate General of the Netherlands in San Francisco Dutch businesses visiting Silicon Valley SILICON VALLEY playbook René Bonvanie of Palo Alto Networks shares his insights for startups coming to Silicon Valley fix your cap table! WHAT INVESTORS Flyr founder Alexander Mans explains how he managed WANTto build a successful business inTO Silicon Valley KNOW Everything you have always wanted to know talk founder about moving to San Francisco to founder Super Evil Megacorp Co-founder Tommy Krul on his adventures as a Dutch Game Coder in Silicon Valley taking the big plunge super evil megacorp Plus: Plus: Plus: Plus: prepare your go build that work hard, read about the journey with a killer pitch play hard: the other side of visual toolbox deck best spots at night silicon valley Foreword You are in charge of 02 your own success! The Inside Silicon Valley Playbook Thank you to the following people was published by the Consulate (without you this magazine could General of the Netherlands in San never have been created!): Silicon Valley is a unique place. The buzz is palpable and infectious. Francisco Competition is relentless. Everyone is working on something big. The Consulate General of the More about Production, design, content and Netherlands in San Francisco : Everywhere you look there are people who can help enrich your interviews by 30X Amsterdam and Gerbert Kunst | Michiel Engelaar | experience. And everyone is willing to share in order to help Startup Delta Business Models Inc. San Francisco Jasper Smit | Alexander Kramer others succeed. For general information about this Investors, founders and experts: publication, please contact us. -

Local Connectedness

Global Startup Ecosystem Report 2018 Article: Local Connectedness Copyright © 2018 Startup Genome LLC. All Rights Reserved. 1 About About the Global Startup Genome Entrepreneurship Network Startup Genome works to increase the success rate The Global Entrepreneurship Network (GEN) operates of startups and improve the performance of startup a platform of projects and programs in 170 countries ecosystems globally. In a collaborative effort with hun- aimed at making it easier for anyone, anywhere to start dreds of public and private organizations in more than 30 countries and scale a business. By fostering deeper cross border collabora- we built the world’s largest primary research on startups, the Voice tion and initiatives between entrepreneurs, investors, researchers, of the Entrepreneur, with +10,000 founders participating each year. policymakers and entrepreneurial support organizations, GEN This allowed us to develop rigorous models that are considered work to fuel healthier start and scale ecosystems that create more the new science of startup ecosystem assessment. jobs, educate individuals, accelerate innovation, and strengthen economic growth. We advise leaders of innovation ministries, agencies, and organi- zations supporting startups, bringing data-driven insights, clarity, Our extensive footprint of national operations and global ver- and focus to actions that produce more scaleups, job creation, ticals in policy, research and programs ensures members have and economic growth. With our partners Global Entrepreneurship uncommon access to the most relevant knowledge, networks, Network and Tech Nation (formerly Tech City UK), and thanks to the communities and programs relative to size of economy, maturity generous support of the Kauffman Foundation, we deliver holistic, of ecosystem, language, culture, geography and more. -

Alberta Innovates Meta-Analysis of Accelerators

Meta-Analysis of ACCELERATORS Report submitted to Alberta Innovates February 9, 2021 Geoff Gregson TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1 INTRODUCTION 7 2 BACKGROUND TO STUDY 10 3 LATEST THINKING ON ACCELERATORS 16 4 INVESTOR-LED ACCELERATORS 22 5 MATCHMAKER & SCALE-UP ACCELERATORS 40 6 DISCUSSION AND SUMMARY 48 REFERENCES 59 APPENDIX A: COMPARATIVE PROFILE OF ACCELERATORS 64 APPENDIX B: ACCELERATOR DESCRIPTIVE DATA 65 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report presents a meta-analysis of business accelerators and draws out relevant insights to inform on the Alberta entrepreneurial ecosystem. A summary of key insights are presented below; ordered under three questions that guide the study. A more detailed discussion of findings can be found in Section 6. Key Insights What are the benefits & challenges of adopting branded globally recognized business accelerators versus developing regional & local accelerator programs? Participation in leading accelerator programs may have a strong ‘positive’ signaling effect distinct from program content. Signaling effects reveal to investors that a founder has undergone a rigorous selection process and may assist founders in recruiting talent & securing other resources. Leading accelerators possess established & repeatable processes that have proven successful. Costs of learning by trial & error to create a home-grown program are difficult to forecast but could be substantial and include direct costs (funding) & indirect costs (reputation). Leading accelerators may provide access to resources that would be difficult to access otherwise. This includes access to seed funding & follow-on investment, extensive mentor & alumni networks, domain experts & peer-to-peer learning with highly qualified founders in the cohort. Seed accelerators may help founders learn when & how to fail & aid in more efficient development decisions. -

Turkish Startup Investments Review

Turkish Startup Investments Review Q2 2021 KPMG Turkey 212 kpmg.com.tr 212.vc Foreword Welcome to the Q2’21 edition of the Turkish Startup Investments Review with the collaboration of KPMG Turkey M&A and the 212 teams. This report is the fourth edition of our quarterly review. Our goal is to highlight key trends, opportunities, and challenges facing the venture capital market globally and in Turkey. Ali Karabey 212 Q2’21 was the period of recovery and optimism. Thanks to the COVID-19 vaccination, the global macroeconomic situation Managing Director [email protected] started to stabilize, which began to create a positive atmosphere around the globe. The uncertainty for the future started to normalize, the global venture market reached a new quarterly record high leaving behind the previous record investment volume in Q1’21. Turkey’s venture ecosystem continued to follow its upwards trend in line with the World. Turkish venture market maintained its remarkable activity, as the volume of startup investments increased by 43% from Q1’21, reaching another quarterly record with 57 deals totaling an investment volume of $727M. In Q2’21 two mega-deals took place with investments exceeding $100M, which constituted 97% of total quarterly funding. Dream Games became the fourth unicorn of Turkey, receiving an Gökhan Kaçmaz investment of $155M with a valuation of $1B, and Getir got one step closer to becoming a decacorn by raising $550M with a KPMG Turkey valuation of $7.5B. Head of M&A Advisory, Partner [email protected] More than a year into the COVID-19 outbreak, the global startup ecosystem looks more robust than ever. -

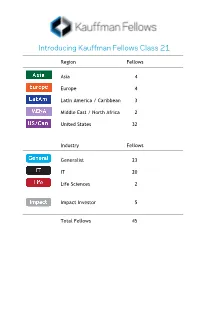

Introducing Kauffman Fellows Class 21

Introducing Kauffman Fellows Class 21 Region Fellows Asia 4 Europe 4 Latin America / Caribbean 3 Middle East / North Africa 2 United States 32 Industry Fellows Generalist 23 IT 20 Life Sciences 2 Impact Investor 5 Total Fellows 45 NICOLAS BERMAN Partner KaszeK Ventures [email protected] +54 (11) 4786-3426 www.kaszek.com Professional Nik is a Partner at KaszeK Ventures, a venture capital firm investing in high-impact technology-based companies whose main focus is Latin America. In addition to capital deployment, the firm actively supports its portfolio companies through value-added strategic guidance and hands-on operational help, leveraging its partners’ successful entrepreneurial backgrounds and extensive network. Before joining KaszeK Ventures, Nik worked for 13 years at MercadoLibre, where he was VP of Advertising, VP of Marketing, Marketing Manager, and covered several roles in the company’s technology and product areas. He led several key projects in search, business intelligence (BI), user experience (UX), and SEO, and created the company’s affiliate program, which is the largest in Latin America. During all these years, Nik has also been a very active advisor and angel investor in the Latin American startup scene. Prior to MercadoLibre, Nik was a Commercial Manager at LG Electronics, where he received the “LG Global Hit Idea” award for his innovative thinking. He currently sits on the boards of several technology companies, including DogHero, Contabilizei, and Pitzi. Education/Personal Nik earned a bachelor’s degree in business administration from the University of Buenos Aires (Argentina). He served as President of AMDIA (Argentina’s direct marketing association), received an Echo Award by the DMA in 2000, is currently an active mentor for Endeavor Argentina, and sits in the board of Educatina, a company focused on democratizing high-quality education across Latin America. -

Y Combinator Accelerates the Hunt for Unicorns

Y Combinator Accelerates the Hunt for Unicorns Faced with increasing competition, the leading accelerator is making start-up know-how widely available as it searches for the next Airbnb. Last summer, Y Combinator (YC), the original start- accelerating the growth of start-ups – offer early- up accelerator that has invested in more than 2,000 stage companies cohort-based, intensive mentoring fledgling firms with a combined value of US$150 for a fixed term of typically three to six months, billion, sent acceptance emails to 11,000 of 15,000 culminating in a “demo day” for potential investors. applicants to its Startup School instead of the Accelerators take a stake in the start-ups in estimated 4,000 originally intended. Rather than exchange for seed funding, although some recent jettisoning the surplus applicants, the company that entrants take no equity, surviving instead on public nurtured the likes of Airbnb, Dropbox, Reddit and funding or corporate sponsorship. The acceptance Quora decided to keep everyone on board. rate at YC’s classic acceleration programme, which is different from its online Startup School offering, is This year, YC will likewise accept all applicants to 1.5 percent, earning it the nickname ‘Harvard of Startup School, a 10-week, free-of-charge massive Silicon Valley’. open online course (MOOC), supplemented with virtual office hours and access to 15,000 founders But similar propositions are now offered by many worldwide. An unannounced number of those who accelerators that have sprung up around the world complete the programme will be given a US$15,000 since 2010, albeit on a less massive scale than YC or grant. -

Accelerators in Silicon Valley: Building Successful Startups

9789462987166 Accelerators in Silicon Valley: Building Successful Startups Accelerators in Silicon Valley: Building Successful Startups Searching for the Next Big Thing Peter Ester Amsterdam University Press This research was made possible by a grant from the Dutch Van Spaendonck Foundation. Cover design: Klaas Wijnberg Typesetting: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 716 6 e-isbn 978 90 4853 868 3 nur 800 doi 10.5117/9789462987166 © P. Ester / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owners and the authors of the book. You should start with the problem that you’re trying to solve in the world and not start with deciding that you want to build a company. Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook To all startups that contribute to a better society through their passion, ambition, and entrepreneurship Table of Contents Foreword 9 Acknowledgements 11 The Interviewees and their Accelerators 15 1 Silicon Valley 21 The DNA of an Entrepreneurial Region Introduction 21 Europe and Silicon Valley 22 Accelerators: Pillars of Silicon Valley’s startup support infra- structure 25 Accelerators: their role, research,