Manga As a Teaching Tool 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, & Anime

SAN DIEGO PUBLIC LIBRARY PATHFINDER Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, & Anime The Central Library has a large collection of comics, the Usual Extra Rarities, 1935–36 (2005) by George graphic novels, manga, anime, and related movies. The Herriman. 741.5973/HERRIMAN materials listed below are just a small selection of these items, many of which are also available at one or more Lions and Tigers and Crocs, Oh My!: A Pearls before of the 35 branch libraries. Swine Treasury (2006) by Stephan Pastis. GN 741.5973/PASTIS Catalog You can locate books and other items by searching the The War Within: One Step at a Time: A Doonesbury library catalog (www.sandiegolibrary.org) on your Book (2006) by G. B. Trudeau. 741.5973/TRUDEAU home computer or a library computer. Here are a few subject headings that you can search for to find Graphic Novels: additional relevant materials: Alan Moore: Wild Worlds (2007) by Alan Moore. cartoons and comics GN FIC/MOORE comic books, strips, etc. graphic novels Alice in Sunderland (2007) by Bryan Talbot. graphic novels—Japan GN FIC/TALBOT To locate materials by a specific author, use the last The Black Diamond Detective Agency: Containing name followed by the first name (for example, Eisner, Mayhem, Mystery, Romance, Mine Shafts, Bullets, Will) and select “author” from the drop-down list. To Framed as a Graphic Narrative (2007) by Eddie limit your search to a specific type of item, such as DVD, Campbell. GN FIC/CAMPBELL click on the Advanced Catalog Search link and then select from the Type drop-down list. -

The Origins of the Magical Girl Genre Note: This First Chapter Is an Almost

The origins of the magical girl genre Note: this first chapter is an almost verbatim copy of the excellent introduction from the BESM: Sailor Moon Role-Playing Game and Resource Book by Mark C. MacKinnon et al. I took the liberty of changing a few names according to official translations and contemporary transliterations. It focuses on the traditional magical girls “for girls”, and ignores very very early works like Go Nagai's Cutie Honey, which essentially created a market more oriented towards the male audience; we shall deal with such things in the next chapter. Once upon a time, an American live-action sitcom called Bewitched, came to the Land of the Rising Sun... The magical girl genre has a rather long and important history in Japan. The magical girls of manga and Japanese animation (or anime) are a rather unique group of characters. They defy easy classification, and yet contain elements from many of the best loved fairy tales and children's stories throughout the world. Many countries have imported these stories for their children to enjoy (most notably France, Italy and Spain) but the traditional format of this particular genre of manga and anime still remains mostly unknown to much of the English-speaking world. The very first magical girl seen on television was created about fifty years ago. Mahoutsukai Sally (or “Sally the Witch”) began airing on Japanese television in 1966, in black and white. The first season of the show proved to be so popular that it was renewed for a second year, moving into the era of color television in 1967. -

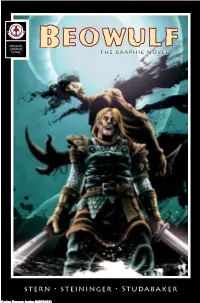

Beowulf: the Graphic Novel Created by Stephen L

ORIGINAL GRAPHIC NOVEL THE GRAPHIC NOVEL TUFSOtTUFJOJOHFSt4UVEBCBLFS Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Writer Stephen L. Stern Artist Christopher Steininger Letterer Chris Studabaker Cover Christopher Steininger For MARKOSIA ENTERPRISES, Ltd. Harry Markos Publisher & Managing Partner Chuck Satterlee Director of Operations Brian Augustyn Editor-In-Chief Tony Lee Group Editor Thomas Mauer Graphic Design & Pre-Press Beowulf: The Graphic Novel created by Stephen L. Stern & Christopher Steininger, based on the translation of the classic poem by Francis Gummere Beowulf: The Graphic Novel. TM & © 2007 Markosia and Stephen L. Stern. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction of any part of this work by any means without the written permission of the publisher is expressly forbidden. Published by Markosia Enterprises, Ltd. Unit A10, Caxton Point, Caxton Way, Stevenage, UK. FIRST PRINTING, October 2007. Harry Markos, Director. Brian Augustyn, EiC. Printed in the EU. Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 Beowulf: The Graphic Novel An Introduction by Stephen L. Stern Writing Beowulf: The Graphic Novel has been one of the most fulfilling experiences of my career. I was captivated by the poem when I first read it decades ago. The translation was by Francis Gummere, and it was a truly masterful work, retaining all of the spirit that the anonymous author (or authors) invested in it while making it accessible to modern readers. “Modern” is, of course, a relative term. The Gummere translation was published in 1910. Yet it held up wonderfully, and over 60 years later, when I came upon it, my imagination was captivated by its powerful descriptions of life in a distant place and time. -

Manga Book Club Handbook

MANGA BOOK CLUB HANDBOOK Starting and making the most of book clubs for manga! STAFF COMIC Director’sBOOK LEGAL Note Charles Brownstein, Executive Director DEFENSE FUND Alex Cox, Deputy Director Everything is changing in 2016, yet the familiar challenges of the past continueBetsy to Gomez, Editorial Director reverberate with great force. This isn’t just true in the broader world, but in comics,Maren Williams, Contributing Editor Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor too. While the boundaries defining representation and content in free expression are protectingexpanding, wethe continue freedom to see to biasedread comics!or outmoded Our viewpoints work protects stifling those advances.Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel readers, creators, librarians, retailers, publishers, and educa- STAFF As you’ll see in this issue of CBLDF Defender, we are working on both ends of the Charles Brownstein, Executive Director torsspectrum who byface providing the threat vital educationof censorship. about the We people monitor whose worklegislation expanded free exBOARD- Alex OF Cox, DIRECTORS Deputy Director pression while simultaneously fighting all attempts to censor creative work in comics.Larry Marder,Betsy Gomez, President Editorial Director and challenge laws that would limit the First Amendment. Maren Williams, Contributing Editor In this issue, we work the former end of the spectrum with a pair of articles spotlightMilton- Griepp, Vice President We create resources that promote understanding of com- Jeff Abraham,Caitlin McCabe,Treasurer Contributing Editor ing the pioneers who advanced diverse content. On page 10, “Profiles in Black Cartoon- Dale Cendali,Robert SecretaryCorn-Revere, Legal Counsel icsing” and introduces the rights you toour some community of the cartoonists is guaranteed. -

First-Year Japanese Through Anime and Manga I

ASIANLAN123 Fall 2015 First-Year Japanese through Anime and Manga I ASIANLAN123: Course Syllabus 3credits Instructor Yuta Mori Email: [email protected] Office phone: 734-936-8808 Office: South Thayer Building 5022 Office Hours: Tuesday 4:00-5:00 pm Course Description Friday 2:30-3:30 pm ASIANLAN123 is the first half of the accelerated first-year Meeting Time Japanese course taught through various types of media, mainly anime and manga. It is designed for students who have some Section1 previous knowledge of Japanese, but less than the equivalent of Time:12:00-1:00 one year’s study of Japanese at the University of Michigan. Classroom: 1265NQ Students will need to obtain a qualifying score on the placement exam to be placed into this course. However, students do not need Section2 any specific knowledge of anime and manga. Upon successful Time:4:00-5:00 completion of ASIANLAN123, students will take ASIANLAN124 Classroom: G311 DENT (First-Year Japanese through Anime and Manga II) in the following semester. ✦ The class meets THREE times a week: Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. What’s new about this course? Main Textbook The course will incorporate at length various media forms into "GENKI I" An Integrated Course in class activities to improve students’ language skills, as well as to Elementary Japanese Second Edition help students have fun. This approach will increase familiarity with aspects of both traditional and modern Japanese culture that are ✦ Make sure that you have the necessary for language competency. Second Edition! This course also encourages students to become autonomous language learners by providing online tools for self-learning (e.g. -

Manga) Market in the US

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics The Diffusion of Foreign Cultural Products: The Case Analysis of Japanese Comics (Manga) Market in the US Takeshi Matsui Working Paper #37, Spring 2009 The Diffusion of Foreign Cultural Products: The Case Analysis of Japanese Comics (Manga) Market in the US * Takeshi Matsui Graduate School Department of Sociology of Commerce and Management Princeton University Hitotsubashi University Princeton, NJ, US 08544 Tokyo, Japan 186-8601 [ Word Count: 8,230] January 2009 * I would like to thank Paul DiMaggio, Russell Belk, Jason Thompson, Stephanie Schacht, and Richard Cohn for helpful feedback and encouragement. This research project is supported by Abe Fellowship (SSRC/Japan Foundation), Josuikai (Alumni Society of Hitotsubashi University), and Japan Productivity Center for Socio-economic Development. Please address correspondence to Takeshi Matsui, Department of Sociology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544. E-mail: [email protected]. The Diffusion of Foreign Cultural Products: The Case Analysis of Japanese Comics (Manga) Market in the US Takeshi Matsui Hitotsubashi University/Princeton University Abstract This paper outlines the historical development of the US manga (Japanese comics) industry from the 1980s through the present in order to address the question why foreign cultural products become popular in offshore markets in spite of cultural difference. This paper focuses on local publishers as “gatekeepers” in the introduction of foreign culture. Using complete data on manga titles published in the US market from 1980 to 2006 (n=1,058), this paper shows what kinds of manga have been translated, published, and distributed for over twenty years and how the competition between the two market leaders, Viz and Tokyopop, created the rapid market growth. -

Graphic Gothic Introduction Julia Round

Graphic Gothic Introduction Julia Round ‘Graphic Gothic’ was the seventh International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference, held at Manchester Metropolitan University in June 2016.1 The event brought together fifty scholars from all over the globe, who explored Gothic under themes such as setting, politics, adaptation, censorship, monstrosity, gender, and corporeality. This issue of Studies in Comics collects selected papers from the conference, alongside expanded versions of the talks given by three of our four keynote speakers: Hannah Berry, Toni Fejzula and Matt Green. It is complemented by a comics section that recalls the conference and reflects the potential of Gothic to inform and inspire as Paul Fisher Davies provides a sketchnoted diary of the event. Defining the Gothic is a difficult task. Baldick and Mighall (2012: 273) note that much of the relevant scholarship to date has primarily applied ‘the broadest kind of negation: the Gothic is cast as the opposite of Enlightenment reason, as it is the opposite of bourgeois literary realism.’ Moers also suggests that the meaning of Gothic ‘is not so easily stated except that it has to do with fear’ (1978: 90). Many Gothic scholars and writers have explored the nature of this fear: attempting to draw out and categorise the metaphorical meanings and affect it can create. H.P. Lovecraft (1927: 41) claims that ‘The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind fear of the unknown’ (Lovecraft 1927: 41) and that this is the basis for ‘the weirdly horrible tale’ as a literary form. Ann Radcliffe (1826: 5) famously separates terror and horror, and later writers and critics such as Devendra Varma (1957), Robert Hume (1969), Stephen King (1981), Gina Wisker and Dale Townshend continue to explore this divide. -

Major Developments in the Evolution of Tabletop Game Design

Major Developments in the Evolution of Tabletop Game Design Frederick Reiber Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences University of California Irvine Irvine, USA [email protected] Abstract—Tabletop game design is very much an incremental these same concepts can and have been used in video game art. Designers build upon the ideas of previous games, often design. improving and combining already defined game mechanics. In Although some of these breakthroughs might be already this work, we look at a collection of the most impactful tabletop game designs, or games that have caused a significant shift in known by long time game designers, it is important to formally the tabletop game design space. This work seeks to record those document these developments. By doing so, we can not only shifts, and does so with the aid of empirical analysis. For each bridge the gap between experienced and novice game design- game, a brief description of the game’s history and mechanics ers, but we can also begin to facilitate scholarly discussion on is given, followed by a discussion on its impact within tabletop the evolution of games. Furthermore, this research is of interest game design. to those within the tabletop game industry as it provides Index Terms—Game Design, Mechanics, Impact. analysis on major developments in the field. It is also our belief that this work can be useful to academics, specifically I. INTRODUCTION those in the fields of game design, game analytics, and game There are many elements that go into creating a successful generation AI. tabletop game. -

GRAPHIC NOVELS in ADVANCED ENGLISH/LANGUAGE ARTS CLASSROOMS: a PHENOMENOLOGICAL CASE STUDY Cary Gillenwater a Dissertation Submi

GRAPHIC NOVELS IN ADVANCED ENGLISH/LANGUAGE ARTS CLASSROOMS: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL CASE STUDY Cary Gillenwater A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Madeleine Grumet James Trier Jeff Greene Lucila Vargas Renee Hobbs © 2012 Cary Gillenwater ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT CARY GILLENWATER: Graphic novels in advanced English/language arts classrooms: A phenomenological case study (Under the direction of Madeleine Grumet) This dissertation is a phenomenological case study of two 12th grade English/language arts (ELA) classrooms where teachers used graphic novels with their advanced students. The primary purpose of this case study was to gain insight into the phenomenon of using graphic novels with these students—a research area that is currently limited. Literature from a variety of disciplines was compared and contrasted with observations, interviews, questionnaires, and structured think-aloud activities for this purpose. The following questions guided the study: (1) What are the prevailing attitudes/opinions held by the ELA teachers who use graphic novels and their students about this medium? (2) What interests do the students have that connect to the phenomenon of comic book/graphic novel reading? (3) How do the teachers and the students make meaning from graphic novels? The findings generally affirmed previous scholarship that the medium of comic books/graphic novels can play a beneficial role in ELA classrooms, encouraging student involvement and ownership of texts and their visual literacy development. The findings also confirmed, however, that teachers must first conceive of literacy as more than just reading and writing phonetic texts if the use of the medium is to be more than just secondary to traditional literacy. -

Korean Webtoons' Transmedia Storytelling

International Journal of Communication 13(2019), 2094–2115 1932–8036/20190005 Snack Culture’s Dream of Big-Screen Culture: Korean Webtoons’ Transmedia Storytelling DAL YONG JIN1 Simon Fraser University, Canada The sociocultural reasons for the growth of webtoons as snack culture and snack culture’s influence in big-screen culture have received little scholarly attention. By employing media convergence supported by transmedia storytelling as a theoretical framework alongside historical and textual analyses, this article historicizes the emergence of snack culture. It divides the evolution of snack culture—in particular, webtoon culture—to big-screen culture into three periods according to the surrounding new media ecology. Then it examines the ways in which webtoons have become a resource for transmedia storytelling. Finally, it addresses the reasons why small snack culture becomes big-screen culture with the case of Along With the Gods: The Two Worlds, which has transformed from a popular webtoon to a successful big-screen movie. Keywords: snack culture, webtoon, transmedia storytelling, big-screen culture, media convergence Snack culture—the habit of consuming information and cultural resources quickly rather than engaging at a deeper level—is becoming representative of the Korean cultural scene. It is easy to find Koreans reading news articles or watching films or dramas on their smartphones on a subway. To cater to this increasing number of mobile users whose tastes are changing, web-based cultural content is churning out diverse subgenres from conventional formats of movies, dramas, cartoons, and novels (Chung, 2014, para. 1). The term snack culture was coined by Wired in 2007 to explain a modern tendency to look for convenient culture that is indulged in within a short duration of time, similar to how people eat snacks such as cookies within a few minutes. -

Korean Webtoonist Yoon Tae Ho: History, Webtoon Industry, and Transmedia Storytelling

International Journal of Communication 13(2019), Feature 2216–2230 1932–8036/2019FEA0002 Korean Webtoonist Yoon Tae Ho: History, Webtoon Industry, and Transmedia Storytelling DAL YONG JIN1 Simon Fraser University, Canada At the Asian Transmedia Storytelling in the Age of Digital Media Conference held in Vancouver, Canada, June 8–9, 2018, webtoonist Yoon Tae Ho as a keynote speaker shared several interesting and important inside stories people would not otherwise hear easily. He also provided his experience with, ideas about, and vision for transmedia storytelling during in-depth interviews with me, the organizer of the conference. I divide this article into two major sections—Yoon’s keynote speech in the first part and the interview in the second part—to give readers engaging and interesting perspectives on webtoons and transmedia storytelling. I organized his talk into several major subcategories based on key dimensions. I expect that this kind of unusual documentation of this famous webtoonist will shed light on our discussions about Korean webtoons and their transmedia storytelling prospects. Keywords: webtoon, manhwa, Yoon Tae Ho, transmedia, history Introduction Korean webtoons have come to make up one of the most significant youth cultures as well as snack cultures: Audiences consume popular culture like webtoons and Web dramas within 10 minutes on their notebook computers or smartphones (Jin, 2019; Miller, 2007). The Korean webtoon industry has grown rapidly, and many talented webtoonists, including Ju Ho-min, Kang Full, and Yoon Tae Ho, are now among the most famous and successful webtoonists since the mid-2000s. Their webtoons—in particular, Yoon Tae Ho’s, including Moss (Ikki, 2008–2009), Misaeng (2012–2013), and Inside Men (2010–in progress)—have gained huge popularity, and all were successfully transformed into films, television dramas, and digital games. -

Using and Analyzing Political Cartoons

USING AND ANALYZING POLITICAL CARTOONS EDUCATION OUTREACH THE COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION This packet of materials was developed by William Fetsko, Colonial Williamsburg Productions, Colonial Williamsburg. © 2001 by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia INTRODUCTION TO LESSONS Political cartoons, or satires, as they were referred to in the eighteenth century, have provided a visual means by which individuals could express their opinions. They have been used throughout history to engage viewers in a discussion about an event, issue, or individual. In addition, they have also become a valuable instructional resource. However, in order for cartoons to be used effectively in the classroom, students must understand how to interpret them. So often they are asked to view a cartoon and explain what is being depicted when they really don’t know how to proceed. With that in mind, the material that follows identifies the various elements cartoonists often incorporate into their work. Once these have been taught to the students, they will then be in a better position to interpret a cartoon. In addition, this package also contains a series of representative cartoons from the Colonial period. Descriptors for these are found in the Appendix. Finally, a number of suggestions are included for the various ways cartoons can be used for instructional purposes. When used properly, cartoons can help meet many needs, and the skill of interpretation is something that has life-long application. 2 © C 2001 olonial  POLITICAL CARTOONS AN INTRODUCTION Cartoons differ in purpose, whether they seek to amuse, as does comic art; make life more bearable, as does the social cartoon; or bring order through governmental action, as does the successful political cartoon.