GRAPHIC NOVELS in ADVANCED ENGLISH/LANGUAGE ARTS CLASSROOMS: a PHENOMENOLOGICAL CASE STUDY Cary Gillenwater a Dissertation Submi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daredevil by Frank Miller Box Set Ebook Free Download

DAREDEVIL BY FRANK MILLER BOX SET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Frank Miller | 1896 pages | 15 Oct 2019 | Marvel Comics | 9781302919108 | English | New York, United States Daredevil By Frank Miller Box Set PDF Book Readers also enjoyed. Elektra 1 Items 1. This is the email address that you previously registered with on angusrobertson. Auction 1. Return to Book Page. Would you like us to keep your Bookworld order history? Again this run is famous for a reason and its definitely an enjoying collection. Dude really wa Despite being the companion piece to Frank Miller's Daredevil Omnibus, they actually put all the best stories in this one. I've never read a Miller book quite this abstract, Sienkiewicz art definitely helps but overall it didn't grab me too much. Seller does not offer returns. This story is brilliant, it shows kingpin at his worst, destroying daredevils life bit by bit. Hardcover , pages. El problema de los libros recopilatorios es que la variedad de artistas puede generar una muy amplia escala de calidad a lo largo de la obra. Delivery Options. Home Gardening International Subscriptions. Sign In Register. However, it's the writing that really sets it apart. Daredevil 7th Series Annual. Get A Copy. Daredevil 5th Series. Accept Close Privacy Policy. Canada Only. But we also get a long fight with Nuke and a comic that quickly becomes more about Captain America than Daredevil. The art is very strange. No No, I don't need my Bookworld details anymore. Average rating 4. Mirallegro rated it really liked it. This omni starts off with a 2 part story with spiderman in which spiderman becomes blind, so daredevil helps out. -

Eerie Archives: Volume 16 Free

FREE EERIE ARCHIVES: VOLUME 16 PDF Bill DuBay,Louise Jones,Faculty of Classics James Warren | 294 pages | 12 Jun 2014 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616554002 | English | Milwaukee, United States Eerie (Volume) - Comic Vine Gather up your wooden stakes, your blood-covered hatchets, and all the skeletons in the darkest depths of your closet, and prepare for a horrifying adventure into the darkest corners of comics history. This vein-chilling second volume showcases work by Eerie Archives: Volume 16 of the best artists to ever work in the comics medium, including Alex Toth, Gray Morrow, Reed Crandall, John Severin, and others. Grab your bleeding glasses and crack open this fourth big volume, collecting Creepy issues Creepy Archives Volume 5 continues the critically acclaimed series that throws back the dusty curtain on a treasure trove of amazing comics art and brilliantly blood-chilling stories. Dark Horse Comics continues to showcase its dedication to publishing the greatest comics of all time with the release of the sixth spooky volume Eerie Archives: Volume 16 our Creepy magazine archives. Creepy Archives Volume 7 collects a Eerie Archives: Volume 16 array of stories from the second great generation of artists and writers in Eerie Archives: Volume 16 history of the world's best illustrated horror magazine. As the s ended and the '70s began, the original, classic creative lineup for Creepy was eventually infused with a slew of new talent, with phenomenal new contributors like Richard Corben, Ken Kelly, and Nicola Cuti joining the ranks of established greats like Reed Crandall, Frank Frazetta, and Al Williamson. This volume of the Creepy Archives series collects more than two hundred pages of distinctive short horror comics in a gorgeous hardcover format. -

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

English Courses, Fall 2019

ENGLISH COURSES, FALL 2019 ENGL 102-012 English Composition II: The Gothic in Literature and Film Dr. Williams TTH 6:00-7:15 Course Description: Engl. 102 belongs to the composition requirement in the English department. However, reading good literature and watching challenging film versions is often as beneficial as taking a strictly grammatical approach and this will be the aim of the particular class offered. With reference to H.P. Lovecraft's essay "Supernatural Horror in Literature", the class will examine various aspects of the Gothic associated with the work of Edgar Allan Poe and Hammer studios. Beginning with readings from "The Fall of the House of Usher," The Pit and the Pendulum", and other works also available from youtube and public domain, the class will study visual depictions of the Gothic in the 1960s Poe/Roger Corman cycles. Following the Mercury Theatre 1938 production of DRACULA by Orson welles, the class will examine how Hammer Studios reproduced the Gothic in the late 50s and 60s with screenings of THE CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN, THE REVENGE OF FRANKENSTEIN, THE HORROR OF DRACULA, DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE, TASTE THE BLOOD OF DRACULA, and DR. JEKYLL AND SISTER HYDE. All written material will be accessible from Project Gutenberg under public domain. Requirements: Five written assignments (five page minimum). ENGL 119-004 Intro to Creative Writing Professor Jordan TTH 2:00-3:15 In this introduction to creative writing course, students will concentrate on two genres—poetry and fiction. We will read contemporary poems and stories paying especial attention to the writers’ strategies for imparting information and learning how to use that craft in our own writing. -

Alan Moore's Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics

Alan Moore’s Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics Jeremy Larance Introduction On May 26, 2014, Marvel Comics ran a full-page advertisement in the New York Times for Alan Moore’s Miracleman, Book One: A Dream of Flying, calling the work “the series that redefined comics… in print for the first time in over 20 years.” Such an ad, particularly one of this size, is a rare move for the comic book industry in general but one especially rare for a graphic novel consisting primarily of just four comic books originally published over thirty years before- hand. Of course, it helps that the series’ author is a profitable lumi- nary such as Moore, but the advertisement inexplicably makes no reference to Moore at all. Instead, Marvel uses a blurb from Time to establish the reputation of its “new” re-release: “A must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” That line came from an article written by Graeme McMillan, but it is worth noting that McMillan’s full quote from the original article begins with a specific reference to Moore: “[Miracleman] represents, thanks to an erratic publishing schedule that both predated and fol- lowed Moore’s own Watchmen, Moore’s simultaneous first and last words on ‘realism’ in superhero comics—something that makes it a must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” Marvel’s excerpt, in other words, leaves out the very thing that McMillan claims is the most important aspect of Miracle- man’s critical reputation as a “missing link” in the study of Moore’s influence on the superhero genre and on the “medium as a whole.” To be fair to Marvel, for reasons that will be explained below, Moore refused to have his name associated with the Miracleman reprints, so the company was legally obligated to leave his name off of all advertisements. -

Queer Here: Poetry to Comic Emma Lennen Katie Jan

Queer Here: Poetry to Comic Emma Lennen Katie Jan Pull Quote: “For the new audience of queer teenagers, the difference between the public and the superhero resonates with them because they feel different from the rest of society.” Consider this: a superhero webcomic. Now consider this: a queer superhero webcomic. If you are anything like me, you were infinitely more elated at the second choice, despite how much you enjoy the first. I love reading queer webcomics because by being online, they bypass publishers who may shoot them down for their queerness. As a result, they manage to elude the systematic repression of the LGBTQA+ community. In the 1950s, when repression of the community was even more prevalent, Frank O’Hara wrote the poem “Homosexuality” to express his journey of acceptance as well as to give advice to future gay people. The changes I made in my translation of the poem “Homosexuality” into a modern webcomic demonstrate the different time periods’ expectations of queer content, while still telling the same story with the same purpose, just in a different genre. Despite the difference between the genres, the first two lines and the copious amount of imagery present in the poem allowed for some near-direct translation. The poem begins with “So we are taking off our masks, are we, and keeping / our mouths shut? As if we’d been pierced by a glance!” (O’Hara 1-2). While usually masks symbolize hiding your true self and therefore have a negative connotation, the poem instead considers it one’s pride. Similarly, for many superheroes, the mask does not represent shame, it represents power and responsibility. -

Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, & Anime

SAN DIEGO PUBLIC LIBRARY PATHFINDER Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, & Anime The Central Library has a large collection of comics, the Usual Extra Rarities, 1935–36 (2005) by George graphic novels, manga, anime, and related movies. The Herriman. 741.5973/HERRIMAN materials listed below are just a small selection of these items, many of which are also available at one or more Lions and Tigers and Crocs, Oh My!: A Pearls before of the 35 branch libraries. Swine Treasury (2006) by Stephan Pastis. GN 741.5973/PASTIS Catalog You can locate books and other items by searching the The War Within: One Step at a Time: A Doonesbury library catalog (www.sandiegolibrary.org) on your Book (2006) by G. B. Trudeau. 741.5973/TRUDEAU home computer or a library computer. Here are a few subject headings that you can search for to find Graphic Novels: additional relevant materials: Alan Moore: Wild Worlds (2007) by Alan Moore. cartoons and comics GN FIC/MOORE comic books, strips, etc. graphic novels Alice in Sunderland (2007) by Bryan Talbot. graphic novels—Japan GN FIC/TALBOT To locate materials by a specific author, use the last The Black Diamond Detective Agency: Containing name followed by the first name (for example, Eisner, Mayhem, Mystery, Romance, Mine Shafts, Bullets, Will) and select “author” from the drop-down list. To Framed as a Graphic Narrative (2007) by Eddie limit your search to a specific type of item, such as DVD, Campbell. GN FIC/CAMPBELL click on the Advanced Catalog Search link and then select from the Type drop-down list. -

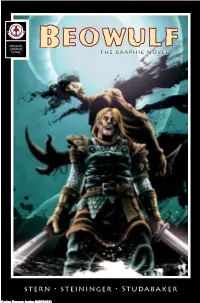

Beowulf: the Graphic Novel Created by Stephen L

ORIGINAL GRAPHIC NOVEL THE GRAPHIC NOVEL TUFSOtTUFJOJOHFSt4UVEBCBLFS Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Writer Stephen L. Stern Artist Christopher Steininger Letterer Chris Studabaker Cover Christopher Steininger For MARKOSIA ENTERPRISES, Ltd. Harry Markos Publisher & Managing Partner Chuck Satterlee Director of Operations Brian Augustyn Editor-In-Chief Tony Lee Group Editor Thomas Mauer Graphic Design & Pre-Press Beowulf: The Graphic Novel created by Stephen L. Stern & Christopher Steininger, based on the translation of the classic poem by Francis Gummere Beowulf: The Graphic Novel. TM & © 2007 Markosia and Stephen L. Stern. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction of any part of this work by any means without the written permission of the publisher is expressly forbidden. Published by Markosia Enterprises, Ltd. Unit A10, Caxton Point, Caxton Way, Stevenage, UK. FIRST PRINTING, October 2007. Harry Markos, Director. Brian Augustyn, EiC. Printed in the EU. Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 Beowulf: The Graphic Novel An Introduction by Stephen L. Stern Writing Beowulf: The Graphic Novel has been one of the most fulfilling experiences of my career. I was captivated by the poem when I first read it decades ago. The translation was by Francis Gummere, and it was a truly masterful work, retaining all of the spirit that the anonymous author (or authors) invested in it while making it accessible to modern readers. “Modern” is, of course, a relative term. The Gummere translation was published in 1910. Yet it held up wonderfully, and over 60 years later, when I came upon it, my imagination was captivated by its powerful descriptions of life in a distant place and time. -

Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko

Law Text Culture Volume 16 Justice Framed: Law in Comics and Graphic Novels Article 10 2012 Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Swinburne University of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Bainbridge, Jason, Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko, Law Text Culture, 16, 2012, 217-242. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Abstract The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. This relationship has also informed superhero comics themselves – going all the way back to Superman’s debut in Action Comics 1 (June 1938). As DC President Paul Levitz says of the development of the superhero: ‘There was an enormous desire to see social justice, a rectifying of corruption. Superman was a fulfillment of a pent-up passion for the heroic solution’ (quoted in Poniewozik 2002: 57). This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Spider-Man, The Question and the Meta-Zone: Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Bainbridge Introduction1 The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Heroic Subjectivity in Frank Miller's the Dark Knight

Ruzbeh BABAEE, Kamelia TALEBIAN SEDEHI, Siamak BABAEE* HEROIC SUBJECTIVITY IN FRANK MILLER’S THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS Abstract. The genre of superhero is challenging. How does one explain the subjectivity of the hero with super- powers, morality norms, justice orders and ideologi- cal backgrounds? Many authors and critics interpret superheroes in cultural, political, religious and social contexts. However, none has investigated a superhero’s subjectivity as a dynamic and in-process phenomenon. The present paper examines the relationship between hero and subjectivity through Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns (1986). Miller shows the necessity of subjective dynamics for the sublime in a model of sub- jectivity that echoes with questions about the subject that has flourished within literary, psychoanalytic and linguistic theories since the mid-twentieth century. Thus, this study employs Julia Kristeva’s concept of subject in 199 process with the aim to indicate that subjectivity is a dynamic phenomenon in Miller’s superhero fiction. Keywords: Batman, subjectivity, justice, morality, sub- ject in process Introduction Recently, there has been a near-deafening whir surrounding comic books. This is partly due, of course, to their adaptation into superhero blockbuster films.1 But something else is also going on. There is a diversifi- cation of the content and its readers along race and gender lines. According to a recent interview with Frederick Luis Aldama, the comic book is “a mate- rial history and an aesthetic configuration” that depicts issues of social jus- tice (“Realities of Graphic Novels” 2). Indeed, social justice and race as artic- ulated within the superhero comic book storytelling mode is the focus of several recent PhD, MA and book-length monograph studies.