Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Charismatic Leadership and Cultural Legacy of Stan Lee

REINVENTING THE AMERICAN SUPERHERO: THE CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP AND CULTURAL LEGACY OF STAN LEE Hazel Homer-Wambeam Junior Individual Documentary Process Paper: 499 Words !1 “A different house of worship A different color skin A piece of land that’s coveted And the drums of war begin.” -Stan Lee, 1970 THESIS As the comic book industry was collapsing during the 1950s and 60s, Stan Lee utilized his charismatic leadership style to reinvent and revive the superhero phenomenon. By leading the industry into the “Marvel Age,” Lee has left a multilayered legacy. Examples of this include raising awareness of social issues, shaping contemporary pop-culture, teaching literacy, giving people hope and self-confidence in the face of adversity, and leaving behind a multibillion dollar industry that employs thousands of people. TOPIC I was inspired to learn about Stan Lee after watching my first Marvel movie last spring. I was never interested in superheroes before this project, but now I have become an expert on the history of Marvel and have a new found love for the genre. Stan Lee’s entire personal collection is archived at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center in my hometown. It contains 196 boxes of interviews, correspondence, original manuscripts, photos and comics from the 1920s to today. This was an amazing opportunity to obtain primary resources. !2 RESEARCH My most important primary resource was the phone interview I conducted with Stan Lee himself, now 92 years old. It was a rare opportunity that few people have had, and quite an honor! I use clips of Lee’s answers in my documentary. -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

HOW to PLAY... BASIC BASIC RULES: This Is the Starting Point – the Foundation RULES on Which the Rest of the Game Is Built

HOW TO PLAY... BASIC BASIC RULES: This is the starting point – the foundation RULES on which the rest of the game is built. These initial rules will be superseded by New Rules during the course of play, but this card should remain on the table at all times. The Basic Rules are: draw 1 card per turn and play 1 card per turn (with no other restrictions such as Hand or Keeper Limits). NEW RULE: To play a New Rule place it face up near the Basic Rules. If it contradicts a New Rule already in play, discard the old rule. New Rules take effect instantly, so all players must immediately follow the New Rule as required. This will often Fluxx is an easy game to learn because it starts out simple—draw 1, cause the player whose turn it is to draw or play additional play 1—and becomes more complicated little by little. Many folks find cards right away, or it may cause other players to immediately that the best way to learn is by jumping right into a game, but that discard some of their cards. usually works best if at least one player in the group has played a Fluxx game before. So, if this is the first time for everyone, someone Examples: After drawing 1 card, you play the Draw 4 New Rule. Now in the group needs to read these rules. But don’t worry, after you’ve the rules require you to Draw 4 cards on each turn, but since you only played the game a few times, everyone will understand! took 1 card before, you must immediately draw 3 more cards. -

Alan Moore's Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics

Alan Moore’s Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics Jeremy Larance Introduction On May 26, 2014, Marvel Comics ran a full-page advertisement in the New York Times for Alan Moore’s Miracleman, Book One: A Dream of Flying, calling the work “the series that redefined comics… in print for the first time in over 20 years.” Such an ad, particularly one of this size, is a rare move for the comic book industry in general but one especially rare for a graphic novel consisting primarily of just four comic books originally published over thirty years before- hand. Of course, it helps that the series’ author is a profitable lumi- nary such as Moore, but the advertisement inexplicably makes no reference to Moore at all. Instead, Marvel uses a blurb from Time to establish the reputation of its “new” re-release: “A must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” That line came from an article written by Graeme McMillan, but it is worth noting that McMillan’s full quote from the original article begins with a specific reference to Moore: “[Miracleman] represents, thanks to an erratic publishing schedule that both predated and fol- lowed Moore’s own Watchmen, Moore’s simultaneous first and last words on ‘realism’ in superhero comics—something that makes it a must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” Marvel’s excerpt, in other words, leaves out the very thing that McMillan claims is the most important aspect of Miracle- man’s critical reputation as a “missing link” in the study of Moore’s influence on the superhero genre and on the “medium as a whole.” To be fair to Marvel, for reasons that will be explained below, Moore refused to have his name associated with the Miracleman reprints, so the company was legally obligated to leave his name off of all advertisements. -

Representing Heroes, Villains and Anti- Heroes in Comics and Graphic

H-Film CFP: Who’s Bad? Representing Heroes, Villains and Anti- Heroes in Comics and Graphic Narratives – A seminar sponsored by the ICLA Research Committee on Comic Studies and Graphic Narratives Discussion published by Angelo Piepoli on Wednesday, September 7, 2016 This is a Call for Papers for a proposed seminar to be held as part of the American Comparative Literature Association's 2017 Annual Meeting. It will take place at Utrecht University in Utrecht, the Netherlands on July 6-9, 2017. Submitters are required to get a free account on the ACLA's website at http://www.acla.org/user/register . Abstracts are limited to 1500 characters, including spaces. If you wish to submit an astract, visit http://www.acla.org/node/12223 . The deadline for paper submission is September 23, 2016. Since the publication of La vida de Lazarillo de Tormes y de sus fortuna y adversidades in 1554, the figure of the anti-hero, which had originated in Homeric literature, has had great literary fortune over the centuries. Satan as the personification of evil, then, was the most interesting character in Paradise Lost by John Milton and initiated a long series of fascinating literary villains. It is interesting to notice that, in a large part of the narratives of these troubled times we are living in, the protagonist of the story is everything but a hero and the most acclaimed characters cross the moral borders quite frequently. This is a fairly common phenomenon in literature as much as in comics and graphic narratives. The advent of the Modern Age of Comic Books in the U.S. -

We Spoke Out: Comic Books and the Holocaust

W E SPOKE OUT COMIC BOOKS W E SPOKE OUT COMIC BOOKS AND THE HOLOCAUST AND NEAL ADAMS RAFAEL MEDOFF CRAIG YOE INTRODUCTION AND THE HOLOCAUST AFTERWORD BY STAN LEE NEAL ADAMS MEDOFF RAFAEL CRAIG YOE LEE STAN “RIVETING!” —Prof. Walter Reich, Former Director, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Long before the Holocaust was widely taught in schools or dramatized in films such asSchindler’s List, America’s youth was learning about the Nazi genocide from Batman, X-Men, and Captain America. Join iconic artist Neal Adams, the legend- ary Stan Lee, Holocaust scholar Dr. Rafael Medoff, and Eisner-winning comics historian Craig Yoe as they take you on an extraordinary journey in We Spoke Out: Comic Books and the Holocaust. We Spoke Out showcases classic comic book stories about the Holocaust and includes commentaries by some of their pres- tigious creators. Writers whose work is featured include Chris Claremont, Archie Goodwin, Al Feldstein, Robert Kanigher, Harvey Kurtzman, and Roy Thomas. Along with Neal Adams (who also drew the cover of this remarkable volume), artists in- clude Gene Colan, Jack Davis, Carmine Infantino, Gil Kane, Bernie Krigstein, Frank Miller, John Severin, and Wally Wood. In We Spoke Out, you’ll see how these amazing comics creators helped introduce an entire generation to a compelling and important subject—a topic as relevant today as ever. ® Visit ISBN: 978-1-63140-888-5 YoeBooks.com idwpublishing.com $49.99 US/ $65.99 CAN ® ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors are grateful to friends and colleagues who assisted with various aspects of this project: Kris Stone and Peter Stone, of Continuity Studios; Gregory Pan, of Marvel Comics; Thomas Wood, Jay Kogan, and Mandy Noack-Barr, of DC Comics; Dan Braun, of New Comic Company (Warren Publications); Corey Mifsud, Cathy Gaines-Mifsud, and Dorothy Crouch of EC Comics; Robert Carter, Jon Gotthold, Michelle Nolan, Thomas Martin, Steve Fears, Rich Arndt, Kevin Reddy, Steve Bergson, and Jeff Reid, who provided information or scans; Jon B. -

{Download PDF} Batman in Brave and the Bold : the Bronze Age

BATMAN IN BRAVE AND THE BOLD : THE BRONZE AGE OMNIBUS VOLUME 3 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mike W. Barr | 904 pages | 07 Sep 2021 | DC Comics | 9781401292829 | English | United States Batman in Brave and the Bold : The Bronze Age Omnibus Volume 3 PDF Book The Authority. Mar 22, Joseph rated it really liked it Shelves: comics-graphic-novels. October 8, Part 3 - Look Homeward, Hero 7 pages. Philip Gipson March 23, Lee and Miller join forces to tell a new version of Dick Grayson's origin in a high-octane tale that unfolds with guest appearances by Superman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, Black Canary and more! Cancel Update. Part 3 - Coffin for a Super-Hero 5 pages. December 10, Manton; Mrs. Part 1 - Mission to Chan 6 pages. Get weekly updates on new arrivals, reviews and recommended reads, links to cool places we find on the net and much more by signing up for our newsletter! Diogo marked it as to-read Jun 13, Related Searches. December 15, Mara marked it as to-read Mar 20, All rights reserved. October 16, Batman by Scott Snyder and Greg Capullo. David marked it as to-read Feb 02, November 14, He-Man and the Masters of the Universe. View: Large Edit cover. Disco of Death! Justice League International. Spectre : The Wrath of the Spectre. Mike W. The first ten or twelve issues that should've been in the JLA omnibus are coming out in a hardcover The Wedding of the Atom. The colors are vivid, the lines are sharp, and there are no noticeable errors. -

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man, Hawkeye Wizard, other villains Vault Breakout stopped, but some escape New Mutants #86 Rusty, Skids Vulture, Tinkerer, Nitro Albany Everyone Arrested Damage Control #1 John, Gene, Bart, (Cap) Wrecking Crew Vault Thunderball and Wrecker escape Avengers #311 Quasar, Peggy Carter, other Avengers employees Doombots Avengers Hydrobase Hydrobase destroyed Captain America #365 Captain America Namor (controlled by Controller) Statue of Liberty Namor defeated Fantastic Four #334 Fantastic Four Constrictor, Beetle, Shocker Baxter Building FF victorious Amazing Spider-Man #326 Spiderman Graviton Daily Bugle Graviton wins Spectacular Spiderman #159 Spiderman Trapster New York Trapster defeated, Spidey gets cosmic powers Wolverine #19 & 20 Wolverine, La Bandera Tiger Shark Tierra Verde Tiger Shark eaten by sharks Cloak & Dagger #9 Cloak, Dagger, Avengers Jester, Fenris, Rock, Hydro-man New York Villains defeated Web of Spiderman #59 Spiderman, Puma Titania Daily Bugle Titania defeated Power Pack #53 Power Pack Typhoid Mary NY apartment Typhoid kills PP's dad, but they save him. Incredible Hulk #363 Hulk Grey Gargoyle Las Vegas Grey Gargoyle defeated, but escapes Moon Knight #8-9 Moon Knight, Midnight, Punisher Flag Smasher, Ultimatum Brooklyn Ultimatum defeated, Flag Smasher killed Doctor Strange #11 Doctor Strange Hobgoblin, NY TV studio Hobgoblin defeated Doctor Strange #12 Doctor Strange, Clea Enchantress, Skurge Empire State Building Enchantress defeated Fantastic Four #335-336 Fantastic -

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Click on Properties and set your Page Orientation to Landscape (11 x 8.5). 3. Under Print Range>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 4. Under Page Handling>Page Scaling select Multiple pages per sheet. 5. Under Page Handling>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 2 by 2. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border. 7. Click OK. ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) TABLE OF CONTENTS Aquaman, 8 Wonder Woman, 6 Batman, 5 Zatanna, 17 Cyborg, 9 Deadman, 16 Deathstroke, 23 Enchantress, 19 Firestorm (Jason Rusch), 13 Firestorm (Ronnie Raymond), 12 The Flash, 20 Fury, 24 Green Arrow, 10 Green Lantern, 7 Hawkman, 14 John Constantine, 22 Madame Xanadu, 21 Mera, 11 Mindwarp, 18 Shade the Changing Man, 15 Superman, 4 ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) 001 DC COMICS SUPERMAN Justice League, Kryptonian, Metropolis, Reporter FROM THE PLANET KRYPTON (Impervious) EMPOWERED BY EARTH’S YELLOW SUN FASTER THAN A SPEEDING BULLET (Charge) (Invulnerability) TO FIGHT FOR TRUTH, JUSTICE AND THE ABLE TO LEAP TALL BUILDINGS (Hypersonic Speed) AMERICAN WAY (Close Combat Expert) MORE POWERFUL THAN A LOCOMOTIVE (Super Strength) Gale-Force Breath Superman can use Force Blast. When he does, he may target an adjacent character and up to two characters that are adjacent to that character. -

Aliens of Marvel Universe

Index DEM's Foreword: 2 GUNA 42 RIGELLIANS 26 AJM’s Foreword: 2 HERMS 42 R'MALK'I 26 TO THE STARS: 4 HIBERS 16 ROCLITES 26 Building a Starship: 5 HORUSIANS 17 R'ZAHNIANS 27 The Milky Way Galaxy: 8 HUJAH 17 SAGITTARIANS 27 The Races of the Milky Way: 9 INTERDITES 17 SARKS 27 The Andromeda Galaxy: 35 JUDANS 17 Saurids 47 Races of the Skrull Empire: 36 KALLUSIANS 39 sidri 47 Races Opposing the Skrulls: 39 KAMADO 18 SIRIANS 27 Neutral/Noncombatant Races: 41 KAWA 42 SIRIS 28 Races from Other Galaxies 45 KLKLX 18 SIRUSITES 28 Reference points on the net 50 KODABAKS 18 SKRULLS 36 AAKON 9 Korbinites 45 SLIGS 28 A'ASKAVARII 9 KOSMOSIANS 18 S'MGGANI 28 ACHERNONIANS 9 KRONANS 19 SNEEPERS 29 A-CHILTARIANS 9 KRYLORIANS 43 SOLONS 29 ALPHA CENTAURIANS 10 KT'KN 19 SSSTH 29 ARCTURANS 10 KYMELLIANS 19 stenth 29 ASTRANS 10 LANDLAKS 20 STONIANS 30 AUTOCRONS 11 LAXIDAZIANS 20 TAURIANS 30 axi-tun 45 LEM 20 technarchy 30 BA-BANI 11 LEVIANS 20 TEKTONS 38 BADOON 11 LUMINA 21 THUVRIANS 31 BETANS 11 MAKLUANS 21 TRIBBITES 31 CENTAURIANS 12 MANDOS 43 tribunals 48 CENTURII 12 MEGANS 21 TSILN 31 CIEGRIMITES 41 MEKKANS 21 tsyrani 48 CHR’YLITES 45 mephitisoids 46 UL'LULA'NS 32 CLAVIANS 12 m'ndavians 22 VEGANS 32 CONTRAXIANS 12 MOBIANS 43 vorms 49 COURGA 13 MORANI 36 VRELLNEXIANS 32 DAKKAMITES 13 MYNDAI 22 WILAMEANIS 40 DEONISTS 13 nanda 22 WOBBS 44 DIRE WRAITHS 39 NYMENIANS 44 XANDARIANS 40 DRUFFS 41 OVOIDS 23 XANTAREANS 33 ELAN 13 PEGASUSIANS 23 XANTHA 33 ENTEMEN 14 PHANTOMS 23 Xartans 49 ERGONS 14 PHERAGOTS 44 XERONIANS 33 FLB'DBI 14 plodex 46 XIXIX 33 FOMALHAUTI 14 POPPUPIANS 24 YIRBEK 38 FONABI 15 PROCYONITES 24 YRDS 49 FORTESQUIANS 15 QUEEGA 36 ZENN-LAVIANS 34 FROMA 15 QUISTS 24 Z'NOX 38 GEGKU 39 QUONS 25 ZN'RX (Snarks) 34 GLX 16 rajaks 47 ZUNDAMITES 34 GRAMOSIANS 16 REPTOIDS 25 Races Reference Table 51 GRUNDS 16 Rhunians 25 Blank Alien Race Sheet 54 1 The Universe of Marvel: Spacecraft and Aliens for the Marvel Super Heroes Game By David Edward Martin & Andrew James McFayden With help by TY_STATES , Aunt P and the crowd from www.classicmarvel.com . -

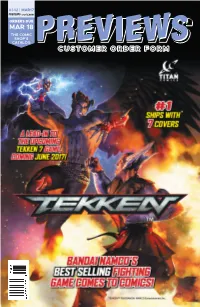

MAR17 World.Com PREVIEWS

#342 | MAR17 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE MAR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Mar17 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 1:36:31 PM Mar17 C2 DH - Buffy.indd 1 2/8/2017 4:27:55 PM REGRESSION #1 PREDATOR: IMAGE COMICS HUNTERS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BUG! THE ADVENTURES OF FORAGER #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT/ YOUNG ANIMAL JOE GOLEM: YOUNGBLOOD #1 OCCULT DETECTIVE— IMAGE COMICS THE OUTER DARK #1 DARK HORSE IDW’S FUNKO UNIVERSE MONTH EVENT IDW ENTERTAINMENT ALL-NEW GUARDIANS TITANS #11 OF THE GALAXY #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS Mar17 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 9:13:17 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Hero Cats: Midnight Over Steller City Volume 2 #1 G ACTION LAB ENTERTAINMENT Stargate Universe: Back To Destiny #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Casper the Friendly Ghost #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Providence Act 2 Limited HC G AVATAR PRESS INC Victor LaValle’s Destroyer #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS Misfi t City #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Swordquest #0 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT James Bond: Service Special G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Spill Zone Volume 1 HC G :01 FIRST SECOND Catalyst Prime: Noble #1 G LION FORGE The Damned #1 G ONI PRESS INC. 1 Keyser Soze: Scorched Earth #1 G RED 5 COMICS Tekken #1 G TITAN COMICS Little Nightmares #1 G TITAN COMICS Disney Descendants Manga Volume 1 GN G TOKYOPOP Dragon Ball Super Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Line of Beauty: The Art of Wendy Pini HC G ART BOOKS Planet of the Apes: The Original Topps Trading Cards HC G COLLECTING AND COLLECTIBLES -

Wolverine: Weapon X Vol. 3: Tomorrow Dies Today Online

gnhdp (Mobile ebook) Wolverine: Weapon X Vol. 3: Tomorrow Dies Today Online [gnhdp.ebook] Wolverine: Weapon X Vol. 3: Tomorrow Dies Today Pdf Free Par Jason Aaron DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Publié le: 2011-03-09Sorti le: 2013-01-31Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 77.Mb Par Jason Aaron : Wolverine: Weapon X Vol. 3: Tomorrow Dies Today before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Wolverine: Weapon X Vol. 3: Tomorrow Dies Today: Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles2 internautes sur 2 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. Une nouvelle version de DeathlokPar PrésenceC'est déjà le dernier tome de cette série après (1) Adamantium Men et (2) Insane in the Brain. Il comprend les épisodes 11 à 16, ainsi que le numéro spécial "Dark reign - the list - Wolverine".Épisodes 11 à 15 - Un nouveau vigilant hante les rues (et les toits) de New York, il s'appelle Slag et sa carrière vient de débuter le soir même. 3 pages après il est froidement abattu par un Deathlok. Puis un autre Deathlok assassine un couple qui allait se former. Encore un autre Deathlok réalise un carnage dans une maternité. Mais que fait Wolverine ? Il est en train d'écluser des bières (et d'autres alcools plus fort) en compagnie de Steve Rogers pour fêter son retour d'entre les morts (dans Reborn). À la fin de cette nuit de beuveries, une inconnue lui apparaît pour lui expliquer qu'elle a subi des vagues de souvenirs du futur avec la liste des cibles des Deathlok et que Captain America est sur la liste (l'autre Captain America, pas Steve Rogers).