Alan Moore's Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Guests We Are Pleased to Announce That the Following Guests Have Confirmed That They Can Attend

Welcome to this progress report for the Festival. Every year we start with a big task… be better than before. With 28 years of festivals under our belts it’s a big ask, but from the feedback we receive expectations are usually exceeded. The biggest source of disappointment from attendees is that they didn’t hear about the festival earlier and missed out on some fantastic weekends. The upcoming 29th Festival of Fantastic Films will be held over the weekend of October 26– 28 in the Manchester Conference Centre (The Pendulum Hotel) and looks set to be another cracker. So do everyone a favour and spread the word. Guests We are pleased to announce that the following guests have confirmed that they can attend Michael Craig Simon Andreu Aldo Lado Dez Skinn Ray Brady 1 A message from the Festival’s Chairman And so we approach the 29th Festival - a position that none of us who began it all could ever have envisioned. We thought that if it went on for about five years, we would be happy. My biggest regret is that I am the only one of that original formation group who is still actively involved in the organisation. I'm not sure if that's because I am a real survivor or if I just don't like quitting. Each year as we look at putting on another Festival, I think of those people who were there at the outset - Harry Nadler, Dave Trengove, and Tony Edwards, without whom the event wouldn’t be what it is. -

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories PAUL A. CRUTCHER DAPTATIONS OF GRAPHIC NOVELS AND COMICS FOR MAJOR MOTION pictures, TV programs, and video games in just the last five Ayears are certainly compelling, and include the X-Men, Wol- verine, Hulk, Punisher, Iron Man, Spiderman, Batman, Superman, Watchmen, 300, 30 Days of Night, Wanted, The Surrogates, Kick-Ass, The Losers, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and more. Nevertheless, how many of the people consuming those products would visit a comic book shop, understand comics and graphic novels as sophisticated, see them as valid and significant for serious criticism and scholarship, or prefer or appreciate the medium over these film, TV, and game adaptations? Similarly, in what ways is the medium complex according to its ad- vocates, and in what ways do we see that complexity in Batman graphic novels? Recent and seminal work done to validate the comics and graphic novel medium includes Rocco Versaci’s This Book Contains Graphic Language, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics. Arguments from these and other scholars and writers suggest that significant graphic novels about the Batman, one of the most popular and iconic characters ever produced—including Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley’s Dark Knight Returns, Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum, and Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s Killing Joke—can provide unique complexity not found in prose-based novels and traditional films. The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2011 r 2011, Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko

Law Text Culture Volume 16 Justice Framed: Law in Comics and Graphic Novels Article 10 2012 Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Swinburne University of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Bainbridge, Jason, Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko, Law Text Culture, 16, 2012, 217-242. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Abstract The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. This relationship has also informed superhero comics themselves – going all the way back to Superman’s debut in Action Comics 1 (June 1938). As DC President Paul Levitz says of the development of the superhero: ‘There was an enormous desire to see social justice, a rectifying of corruption. Superman was a fulfillment of a pent-up passion for the heroic solution’ (quoted in Poniewozik 2002: 57). This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Spider-Man, The Question and the Meta-Zone: Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Bainbridge Introduction1 The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. -

A Chilling Look Back at Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale's

Jeph Loeb Sale and Tim at A back chilling look Batman and Scarecrow TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 9 No.60 Oct. 201 2 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 COMiCs HALLOWEEN HEROES AND VILLAINS: • SOLOMON GRUNDY • MAN-WOLF • LORD PUMPKIN • and RUTLAND, VERMONT’s Halloween Parade , bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD ’ s SCARECROW i . Volume 1, Number 60 October 2012 Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! The Retro Comics Experience! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks COVER ARTIST Tim Sale COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Scott Andrews Tony Isabella Frank Balkin David Anthony Kraft Mike W. Barr Josh Kushins BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 Bat-Blog Aaron Lopresti FLASHBACK: Looking Back at Batman: The Long Halloween . .3 Al Bradford Robert Menzies Tim Sale and Greg Wright recall working with Jeph Loeb on this landmark series Jarrod Buttery Dennis O’Neil INTERVIEW: It’s a Matter of Color: with Gregory Wright . .14 Dewey Cassell James Robinson The celebrated color artist (and writer and editor) discusses his interpretations of Tim Sale’s art Nicholas Connor Jerry Robinson Estate Gerry Conway Patrick Robinson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Scarecrow . .19 Bob Cosgrove Rootology The history of one of Batman’s oldest foes, with comments from Barr, Davis, Friedrich, Grant, Jonathan Crane Brian Sagar and O’Neil, plus Golden Age great Jerry Robinson in one of his last interviews Dan Danko Tim Sale FLASHBACK: Marvel Comics’ Scarecrow . .31 Alan Davis Bill Schelly Yep, there was another Scarecrow in comics—an anti-hero with a patchy career at Marvel DC Comics John Schwirian PRINCE STREET NEWS: A Visit to the (Great) Pumpkin Patch . -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Orwellian Methods of Social Control in Contemporary Dystopian Literature

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio Documental de la Universidad de Valladolid FACULTAD de FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO de FILOLOGÍA INGLESA Grado en Estudios Ingleses TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO A Nightmarish Tomorrow: Orwellian Methods of Social Control in Contemporary Dystopian Literature Pablo Peláez Galán Tutora: Tamara Pérez Fernández 2014/2015 ABSTRACT Dystopian literature is considered a branch of science fiction which writers use to portray a futuristic dark vision of the world, generally dominated by technology and a totalitarian ruling government that makes use of whatever means it finds necessary to exert a complete control over its citizens. George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) is considered a landmark of the dystopian genre by portraying a futuristic London ruled by a totalitarian, fascist party whose main aim is the complete control over its citizens. This paper will analyze two examples of contemporary dystopian literature, Philip K. Dick’s “Faith of Our Fathers” (1967) and Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta (1982-1985), to see the influence that Orwell’s dystopia played in their construction. It will focus on how these two works took Orwell’s depiction of a totalitarian state and the different methods of control it employs to keep citizens under complete control and submission, and how they apply them into their stories. KEYWORDS: Orwell, V for Vendetta , Faith of Our Fathers, social control, manipulation, submission. La literatura distópica es considerada una rama de la ciencia ficción, usada por los escritores para retratar una visión oscura y futurista del mundo, normalmente dominado por la tecnología y por un gobierno totalitario que hace uso de todos los medios que sean necesarios para ejercer un control total sobre sus ciudadanos. -

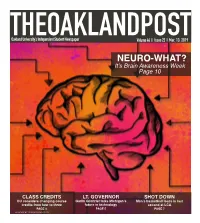

NEURO-WHAT? It’S Brain Awareness Week Page 10

THEOAKLANDPOSTOakland University’s Independent Student Newspaper Volume 44 Issue 22 Mar. 13, 2019 l l NEURO-WHAT? It’s Brain Awareness Week Page 10 CLASS CREDITS LT. GOVERNOR SHOT DOWN OU considers changing course Garlin Gilchrist talks Michigan’s Men’s basketball loses in last credits from four to three future in technology second at LCA PAGE 4 PAGE 5 PAGE 7 GRAPHIC BY PRAKHYA CHILUKURI MARCH 13, 2019 | 2 THIS WEEK PHOTO OF THE WEEK THEOAKLANDPOST EDITORIAL BOARD AuJenee Hirsch Laurel Kraus Editor-in-Chief Managing Editor [email protected] [email protected] 248.370.4266 248.370.2537 Elyse Gregory Patrick Sullivan Photo Editor Web Editor [email protected] [email protected] 248.370.4266 EDITORS COPY&VISUAL Katie Valley Campus Editor Mina Fuqua Chief Copy Editor [email protected] Jessica Trudeau Copy Editor Zoe Garden Copy Editor Trevor Tyle Life&Arts Editor Erin O’Neill Graphic Designer [email protected] Prakhya Chilukuri Graphic Assistant Michael Pearce Sports Editor Ryan Pini Photographer [email protected] Nicole Morsfield Photographer Samuel Summers Photographer Jordan Jewell Engagement Editor Sergio Montanez Photographer [email protected] PRIDE MONTH SPEAKER Poet and educator J Mase III opens Pride Month with pow- REPORTERS DISTRIBUTION erful slam poetry about his experiences being black and transgender, and talks about Benjamin Hume Staff Reporter Kat Malokofsky Distribution Director Distributor combating white supremacy and false allyship. PHOTO / NICOLE MORSFIELD Dean Vaglia Staff Reporter Alexander Pham -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J.