Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Alan Moore's Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics

Alan Moore’s Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics Jeremy Larance Introduction On May 26, 2014, Marvel Comics ran a full-page advertisement in the New York Times for Alan Moore’s Miracleman, Book One: A Dream of Flying, calling the work “the series that redefined comics… in print for the first time in over 20 years.” Such an ad, particularly one of this size, is a rare move for the comic book industry in general but one especially rare for a graphic novel consisting primarily of just four comic books originally published over thirty years before- hand. Of course, it helps that the series’ author is a profitable lumi- nary such as Moore, but the advertisement inexplicably makes no reference to Moore at all. Instead, Marvel uses a blurb from Time to establish the reputation of its “new” re-release: “A must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” That line came from an article written by Graeme McMillan, but it is worth noting that McMillan’s full quote from the original article begins with a specific reference to Moore: “[Miracleman] represents, thanks to an erratic publishing schedule that both predated and fol- lowed Moore’s own Watchmen, Moore’s simultaneous first and last words on ‘realism’ in superhero comics—something that makes it a must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” Marvel’s excerpt, in other words, leaves out the very thing that McMillan claims is the most important aspect of Miracle- man’s critical reputation as a “missing link” in the study of Moore’s influence on the superhero genre and on the “medium as a whole.” To be fair to Marvel, for reasons that will be explained below, Moore refused to have his name associated with the Miracleman reprints, so the company was legally obligated to leave his name off of all advertisements. -

Air Force Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps AFJROTC

Air Force Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps AFJROTC Arlington Independent School District Developing citizens of character dedicated to serving their community and nation. 1 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 TX-031 AFJROTC WING Texas 31st Air Force Junior ROTC Wing was established in Arlington Independent School District in 1968 by an agreement between the Arlington Independent School District and the United States Air Force. The Senior Aerospace Science Instructor (SASI) is a retired Air Force officer. Aerospace Science Instructors (ASIs) are retired senior non-commissioned officers. These instructors have an extensive background in leadership, management, instruction and mentorship. The students who enroll in Air Force Junior ROTC are referred to as “Cadets”. The entire group of cadets is referred to as a Wing. The Cadet Wing is “owned”, managed and operated by students referred to as Cadet Officers and Cadet Non-commissioned Officers. Using this cadet organization structure, allows cadets to learn leadership skills through direct activities. The attached cadet handbook contains policy guidance, requirements and rules of conduct for AFJROTC cadets. Each cadet will study this handbook and be held responsible for knowing its contents. The handbook also describes cadet operations, cadet rank and chain of command, job descriptions, procedures for promotions, awards, grooming standards, and uniform wear. It supplements AFJROTC and Air Force directives. This guide establishes the standards that ensure the entire Cadet Wing works together towards a common goal of proficiency that will lead to pride in achievement for our unit. Your knowledge of Aerospace Science, development as a leader, and contributions to your High School and community depends upon the spirit in which you abide by the provisions of this handbook. -

Web Layout and Content Guide Table of Contents

Web Layout and Content Guide Table of Contents Working with Pages ...................................................................................... 3 Adding Media ................................................................................................ 5 Creating Page Intros...................................................................................... 7 Using Text Modules ...................................................................................... 9 Using Additional Modules ............................................................................19 Designing a Page Layout .............................................................................24 Web Layout and Content Guide 2 Working with Pages All University Communications-created sites use Wordpress as their content management system. Content is entered and pages are created through a web browser. A web address will be provided to you, allowing you to access the Wordpress Dashboard for your site with your Unity ID via the “Wrap Account” option. Web Layout and Content Guide 3 Existing and New Pages Site Navigation/Links In the Wordpress Dashboard the “Pages” section — accessible in the left-hand menu — allows you to view all the pages Once a new page has been published it can be added to the appropriate place in the site’s navigation structure under that have been created for your site, and select the one you want to edit. You can also add a new page via the left-hand “Appearance” > “Menus” in the left-hand menu. The new page should appear in the “Most Recent” list on the left. It menu, or the large button in the “All Pages” view or “Tree View.” Once you have created a new page and you are in the can then be selected and put into the navigation by clicking the “Add to Menu” button. The page will be added to the “Edit Page” view, be sure to give the page a proper Title. bottom of the “Menu Structure” by default. -

Reframe and Imdbpro Announce New Collaboration to Recognize Standout Gender-Balanced Film and TV Projects

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contacts: June 7, 2018 For Sundance Institute: Jenelle Scott 310.360.1972 [email protected] For Women In Film: Catherine Olim 310.967.7242 [email protected] For IMDbPro: Casey De La Rosa 310.573.0632 [email protected] ReFrame and IMDbPro Announce New Collaboration to Recognize Standout Gender-balanced Film and TV Projects The ReFrame Stamp is being Awarded to 12 Films from 2017 including Everything, Everything; Girls Trip; Lady Bird; The Post; and Wonder Woman Los Angeles, CA — ReFrame™, a coalition of industry professionals and partner companies founded by Women In Film and Sundance Institute whose mission is to increase the number of women of all backgrounds working in film, TV and media, and IMDbPro (http://www.imdbpro.com/), the leading information resource for the entertainment industry, today announced a new collaboration that leverages the authoritative data and professional resources of IMDbPro to recognize standout, gender- balanced film and TV projects. ReFrame is using IMDbPro data to determine recipients of a new ReFrame Stamp, and IMDbPro is providing digital promotion of ReFrame activities (imdb.com/reframe). Also announced today was the first class of ReFrame Stamp feature film recipients based on an extensive analysis of IMDbPro data on the top 100 domestic-grossing films of 2017. The recipients include Warner Bros.’ Everything, Everything, Universal’s Girls Trip, A24’s Lady Bird, Twentieth Century Fox’s The Post and Warner Bros.’ Wonder Woman. The ReFrame Stamp serves as a mark of distinction for projects that have demonstrated success in gender-balanced film and TV productions based on criteria developed by ReFrame in consultation with ReFrame Ambassadors (complete list below), producers and other industry experts. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II a Master's Thesis Presented to College of Arts & Sciences Departmen

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II A Master’s Thesis Presented To College of Arts & Sciences Department of Communications and Humanities _______________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree _______________________________ SUNY Polytechnic Institute By David Dellecese May 2018 © 2018 David Dellecese Approval Page SUNY Polytechnic Institute DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATIONS AND HUMANITIES INFORMATION DESIGN AND TECHNOLOGY MS PROGRAM Approved and recommended for acceptance as a thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Information Design + Technology. _________________________ DATE ________________________________________ Kathryn Stam Thesis Advisor ________________________________________ Ryan Lizardi Second Reader ________________________________________ Russell Kahn Instructor 1 ABSTRACT American comic books were a relatively, but quite popular form of media during the years of World War II. Amid a limited media landscape that otherwise consisted of radio, film, newspaper, and magazines, comics served as a useful tool in engaging readers of all ages to get behind the war effort. The aims of this research was to examine a sampling of messages put forth by comic book publishers before and after American involvement in World War II in the form of fictional comic book stories. In this research, it is found that comic book storytelling/messaging reflected a theme of American isolation prior to U.S. involvement in the war, but changed its tone to become a strong proponent for American involvement post-the bombing of Pearl Harbor. This came in numerous forms, from vilification of America’s enemies in the stories of super heroics, the use of scrap, rubber, paper, or bond drives back on the homefront to provide resources on the frontlines, to a general sense of patriotism. -

Caderno De Resumos

CADERNO DE RESUMOS ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÕES E ARTES UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO 21 A 23 DE AGOSTO DE 2019 1 CADERNO DE RESUMOS ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÕES E ARTES UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO 21 A 23 DE AGOSTO DE 2019 Realização Observatório de Histórias em Quadrinhos da Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo 2 6as Jornadas Internacionais de Histórias em Quadrinhos – Caderno de Resumos Realização Observatório de Histórias em Quadrinhos da ECA-USP Comissão Organizadora Nobu Chinen (UFRJ) Paulo Ramos (UNIFESP) Roberto Elísio dos Santos (Observatório de Histórias em Quadrinhos / ECA-USP) Waldomiro Vergueiro (ECA-USP) Comissão Executiva Beatriz Sequeira (ECA-USP) Celbi Pegoraro (ECA-USP) Ediliane Boff (FIAM) Nobu Chinen (UFRJ) Edição Celbi Pegoraro Ediliane de Oliveira Boff Nobu Chinen Paulo Ramos Roberto Elísio dos Santos Waldomiro Vergueiro Ilustração da capa Will Apoio Comix Departamento de Informação e Cultura da ECA-USP Departamento de Letras da Universidade Federal de São Paulo Editora Peirópolis Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Comunicação da ECA-USP 6as Jornadas Internacionais de Histórias em Quadrinhos – Caderno de Resumos. 21 a 23 de agosto de 2019, São Paulo. Organizado por Nobu Chinen, Paulo Ramos, Roberto Elísio dos Santos e Waldomiro Vergueiro. São Paulo: Observatório de Histórias em Quadrinhos da Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo, 2019. ISSN 2237-0323 1 . Histórias em Quadrinhos. 2. Jornadas Internacionais de Histórias em Quadrinhos. 3 SUMÁRIO Apresentação 5 Programação Geral 6 Resumos / Eixos Temáticos Quadrinhos, Educação e Cultura 11 Quadrinhos, História e Sociedade 93 Quadrinhos, Linguagem e Gêneros Textuais/Discursivos 163 Quadrinhos, Literatura e Arte 210 Quadrinhos, Comunicação e Mercado 245 Quadrinhos, Novas Mídias e Tecnologias 255 4 APRESENTAÇÃO Temos a satisfação de apresentar os resumos aprovados para apresentação nas 5as Jornadas Internacionais de Histórias em Quadrinhos. -

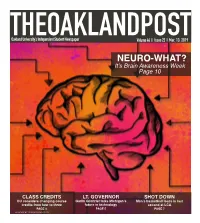

NEURO-WHAT? It’S Brain Awareness Week Page 10

THEOAKLANDPOSTOakland University’s Independent Student Newspaper Volume 44 Issue 22 Mar. 13, 2019 l l NEURO-WHAT? It’s Brain Awareness Week Page 10 CLASS CREDITS LT. GOVERNOR SHOT DOWN OU considers changing course Garlin Gilchrist talks Michigan’s Men’s basketball loses in last credits from four to three future in technology second at LCA PAGE 4 PAGE 5 PAGE 7 GRAPHIC BY PRAKHYA CHILUKURI MARCH 13, 2019 | 2 THIS WEEK PHOTO OF THE WEEK THEOAKLANDPOST EDITORIAL BOARD AuJenee Hirsch Laurel Kraus Editor-in-Chief Managing Editor [email protected] [email protected] 248.370.4266 248.370.2537 Elyse Gregory Patrick Sullivan Photo Editor Web Editor [email protected] [email protected] 248.370.4266 EDITORS COPY&VISUAL Katie Valley Campus Editor Mina Fuqua Chief Copy Editor [email protected] Jessica Trudeau Copy Editor Zoe Garden Copy Editor Trevor Tyle Life&Arts Editor Erin O’Neill Graphic Designer [email protected] Prakhya Chilukuri Graphic Assistant Michael Pearce Sports Editor Ryan Pini Photographer [email protected] Nicole Morsfield Photographer Samuel Summers Photographer Jordan Jewell Engagement Editor Sergio Montanez Photographer [email protected] PRIDE MONTH SPEAKER Poet and educator J Mase III opens Pride Month with pow- REPORTERS DISTRIBUTION erful slam poetry about his experiences being black and transgender, and talks about Benjamin Hume Staff Reporter Kat Malokofsky Distribution Director Distributor combating white supremacy and false allyship. PHOTO / NICOLE MORSFIELD Dean Vaglia Staff Reporter Alexander Pham -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Why No Wonder Woman?

Why No Wonder Woman? A REPORT ON THE HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN AND A CALL TO ACTION!! Created for Wonder Woman Fans Everywhere Introduction by Jacki Zehner with Report Written by Laura Moore April 15th, 2013 Wonder Woman - p. 2 April 15th, 2013 AN INTRODUCTION AND FRAMING “The destiny of the world is determined less by battles that are lost and won than by the stories it loves and believes in” – Harold Goddard. I believe in the story of Wonder Woman. I always have. Not the literal baby being made from clay story, but the metaphorical one. I believe in a story where a woman is the hero and not the victim. I believe in a story where a woman is strong and not weak. Where a woman can fall in love with a man, but she doesnʼt need a man. Where a woman can stand on her own two feet. And above all else, I believe in a story where a woman has superpowers that she uses to help others, and yes, I believe that a woman can help save the world. “Wonder Woman was created as a distinctly feminist role model whose mission was to bring the Amazon ideals of love, peace, and sexual equality to ʻa world torn by the hatred of men.ʼ”1 While the story of Wonder Woman began back in 1941, I did not discover her until much later, and my introduction didnʼt come at the hands of comic books. Instead, when I was a little girl I used to watch the television show starring Lynda Carter, and the animated television series, Super Friends. -

Tom Hanks Halle Berry Martin Sheen Brad Pitt Robert Deniro Jodie Foster Will Smith Jay Leno Jared Leto Eli Roth Tom Cruise Steven Spielberg

TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND MARION COTILLARD KIRSTEN DUNST STEVE BUSCEMI ELIJAH WOOD RESSE WITHERSPOON MICKEY ROURKE AUDREY HEPBURN STEVE CARELL AL PACINO JIM CARREY SHARON STONE MEL GIBSON 2017-18 CATALOG SAM NEILL CHRIS HEMSWORTH MICHAEL SHANNON KIRK DOUGLAS ICE-T RENEE ZELLWEGER ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG CONTENTS 2 INDEPENDENT | FOREIGN | ARTHOUSE 23 HORROR | SLASHER | THRILLER 38 FACTUAL | HISTORICAL 44 NATURE | SUPERNATURAL MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN 45 WESTERNS SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO 48 20TH CENTURY TELEVISION LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA 54 SCI-FI | FANTASY | SPACE DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW 57 POLITICS | ESPIONAGE | WAR SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST 60 ART | CULTURE | CELEBRITY MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE 64 ANIMATION | FAMILY WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND 78 CRIME | DETECTIVE