Richard Marsh's the Beetle (1897): a Late-Victorian Popular Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man, Hawkeye Wizard, other villains Vault Breakout stopped, but some escape New Mutants #86 Rusty, Skids Vulture, Tinkerer, Nitro Albany Everyone Arrested Damage Control #1 John, Gene, Bart, (Cap) Wrecking Crew Vault Thunderball and Wrecker escape Avengers #311 Quasar, Peggy Carter, other Avengers employees Doombots Avengers Hydrobase Hydrobase destroyed Captain America #365 Captain America Namor (controlled by Controller) Statue of Liberty Namor defeated Fantastic Four #334 Fantastic Four Constrictor, Beetle, Shocker Baxter Building FF victorious Amazing Spider-Man #326 Spiderman Graviton Daily Bugle Graviton wins Spectacular Spiderman #159 Spiderman Trapster New York Trapster defeated, Spidey gets cosmic powers Wolverine #19 & 20 Wolverine, La Bandera Tiger Shark Tierra Verde Tiger Shark eaten by sharks Cloak & Dagger #9 Cloak, Dagger, Avengers Jester, Fenris, Rock, Hydro-man New York Villains defeated Web of Spiderman #59 Spiderman, Puma Titania Daily Bugle Titania defeated Power Pack #53 Power Pack Typhoid Mary NY apartment Typhoid kills PP's dad, but they save him. Incredible Hulk #363 Hulk Grey Gargoyle Las Vegas Grey Gargoyle defeated, but escapes Moon Knight #8-9 Moon Knight, Midnight, Punisher Flag Smasher, Ultimatum Brooklyn Ultimatum defeated, Flag Smasher killed Doctor Strange #11 Doctor Strange Hobgoblin, NY TV studio Hobgoblin defeated Doctor Strange #12 Doctor Strange, Clea Enchantress, Skurge Empire State Building Enchantress defeated Fantastic Four #335-336 Fantastic -

Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko

Law Text Culture Volume 16 Justice Framed: Law in Comics and Graphic Novels Article 10 2012 Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Swinburne University of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Bainbridge, Jason, Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko, Law Text Culture, 16, 2012, 217-242. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Abstract The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. This relationship has also informed superhero comics themselves – going all the way back to Superman’s debut in Action Comics 1 (June 1938). As DC President Paul Levitz says of the development of the superhero: ‘There was an enormous desire to see social justice, a rectifying of corruption. Superman was a fulfillment of a pent-up passion for the heroic solution’ (quoted in Poniewozik 2002: 57). This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Spider-Man, The Question and the Meta-Zone: Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Bainbridge Introduction1 The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. -

Aliens of Marvel Universe

Index DEM's Foreword: 2 GUNA 42 RIGELLIANS 26 AJM’s Foreword: 2 HERMS 42 R'MALK'I 26 TO THE STARS: 4 HIBERS 16 ROCLITES 26 Building a Starship: 5 HORUSIANS 17 R'ZAHNIANS 27 The Milky Way Galaxy: 8 HUJAH 17 SAGITTARIANS 27 The Races of the Milky Way: 9 INTERDITES 17 SARKS 27 The Andromeda Galaxy: 35 JUDANS 17 Saurids 47 Races of the Skrull Empire: 36 KALLUSIANS 39 sidri 47 Races Opposing the Skrulls: 39 KAMADO 18 SIRIANS 27 Neutral/Noncombatant Races: 41 KAWA 42 SIRIS 28 Races from Other Galaxies 45 KLKLX 18 SIRUSITES 28 Reference points on the net 50 KODABAKS 18 SKRULLS 36 AAKON 9 Korbinites 45 SLIGS 28 A'ASKAVARII 9 KOSMOSIANS 18 S'MGGANI 28 ACHERNONIANS 9 KRONANS 19 SNEEPERS 29 A-CHILTARIANS 9 KRYLORIANS 43 SOLONS 29 ALPHA CENTAURIANS 10 KT'KN 19 SSSTH 29 ARCTURANS 10 KYMELLIANS 19 stenth 29 ASTRANS 10 LANDLAKS 20 STONIANS 30 AUTOCRONS 11 LAXIDAZIANS 20 TAURIANS 30 axi-tun 45 LEM 20 technarchy 30 BA-BANI 11 LEVIANS 20 TEKTONS 38 BADOON 11 LUMINA 21 THUVRIANS 31 BETANS 11 MAKLUANS 21 TRIBBITES 31 CENTAURIANS 12 MANDOS 43 tribunals 48 CENTURII 12 MEGANS 21 TSILN 31 CIEGRIMITES 41 MEKKANS 21 tsyrani 48 CHR’YLITES 45 mephitisoids 46 UL'LULA'NS 32 CLAVIANS 12 m'ndavians 22 VEGANS 32 CONTRAXIANS 12 MOBIANS 43 vorms 49 COURGA 13 MORANI 36 VRELLNEXIANS 32 DAKKAMITES 13 MYNDAI 22 WILAMEANIS 40 DEONISTS 13 nanda 22 WOBBS 44 DIRE WRAITHS 39 NYMENIANS 44 XANDARIANS 40 DRUFFS 41 OVOIDS 23 XANTAREANS 33 ELAN 13 PEGASUSIANS 23 XANTHA 33 ENTEMEN 14 PHANTOMS 23 Xartans 49 ERGONS 14 PHERAGOTS 44 XERONIANS 33 FLB'DBI 14 plodex 46 XIXIX 33 FOMALHAUTI 14 POPPUPIANS 24 YIRBEK 38 FONABI 15 PROCYONITES 24 YRDS 49 FORTESQUIANS 15 QUEEGA 36 ZENN-LAVIANS 34 FROMA 15 QUISTS 24 Z'NOX 38 GEGKU 39 QUONS 25 ZN'RX (Snarks) 34 GLX 16 rajaks 47 ZUNDAMITES 34 GRAMOSIANS 16 REPTOIDS 25 Races Reference Table 51 GRUNDS 16 Rhunians 25 Blank Alien Race Sheet 54 1 The Universe of Marvel: Spacecraft and Aliens for the Marvel Super Heroes Game By David Edward Martin & Andrew James McFayden With help by TY_STATES , Aunt P and the crowd from www.classicmarvel.com . -

Richard Marsh's the Beetle (1897): Popular Fiction in Late-Victorian Britain

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by City Research Online Vuohelainen, M. (2006). Richard Marsh’s The Beetle (1897): A Late-Victorian Popular Novel. Working With English: medieval and modern language, literature and drama, 2(1), pp. 89-100. City Research Online Original citation: Vuohelainen, M. (2006). Richard Marsh’s The Beetle (1897): A Late-Victorian Popular Novel. Working With English: medieval and modern language, literature and drama, 2(1), pp. 89-100. Permanent City Research Online URL: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/16325/ Copyright & reuse City University London has developed City Research Online so that its users may access the research outputs of City University London's staff. Copyright © and Moral Rights for this paper are retained by the individual author(s) and/ or other copyright holders. All material in City Research Online is checked for eligibility for copyright before being made available in the live archive. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to from other web pages. Versions of research The version in City Research Online may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check the Permanent City Research Online URL above for the status of the paper. Enquiries If you have any enquiries about any aspect of City Research Online, or if you wish to make contact with the author(s) of this paper, please email the team at [email protected]. Richard Marsh’s The Beetle (1897): a late-Victorian popular novel by Minna Vuohelainen Birkbeck, University of London This paper deals with the publication history and popular appeal of a novel which, when first published in 1897, was characterised by contemporary readers and reviewers as “surprising and ingenious”, “weird”, “thrilling”, “really exciting”, “full of mystery” and “extremely powerful”. -

Statues and Figurines

NEW STATUES! 1. The Thing Premium Format 550.00 2. Thor Premium Format 900.00 3. Hulk Premium Format 1500.00 4. Art Asylum Hulk 299.00 5. Juggernaut 450.00 6. Wolverine vs Sabretooth 699.00 7. Ironman Comiquette 449.00 8. Mark Newman Sabretooth 245.00 9. Planet Hulk Green Scar vs Silver Savage 500.00 10. Bowen Retro Green Hulk 279.99 11. Moonlight Silver 299.99 12. Hulk Planet Hulk Version 299.99 13. X-Men vs Sentinel 249.99 14. Red Hulk 225.99 15. Art Asylum Captain America 199.00 16. Kotobukiya Ltd Ed. Hulk 225.00 17. Kotobukiya Ltd Ed. Abomination 200.00 18. Bowen Wolverine Action 249.99 19. Sgt Rock 89.99 20. Bowen Shiflet Bros Hulk 299.00 21. Hulk Hard Hero 229.00 22. Superman 199.99 23. Wolverine Diorama 169.99 24. Dead pool 275.00 25. Dead pool 275.00 26. Wolverine with Whiskey 150.00 27. Hulk Marvel Origins 139.00 28. Captain America Resin Bank 24.99 29. Hulk Fine Art Bust 99.99 30. Captain America Mini Bust 89.99 31. Flash vs Gorilla Grodd 200.00 32. Bishoujo Batgirl 59.99 33. Harley Quinn 90.00 34. Swamp Thing 95.00 35. Flaming Carrot 229.99 36. Death 99.99 37. Sandman 99.99 38. BW Batman 79.99 39. ONI Chan 40.00 40. Umbrella Acsdemy 129.99 41. Lord Of The Rings 129.99 42. Silver Surfer 150.00 43. X-Men Origins Wolverine Bust Only 39.99 44. X-Men Origins Wolverine Bust Bluray 80.00 45. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Maritime Craft Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: A thesaurus of maritime craft. Date: February 2020 MARITIME CRAFT CLASS LIST AIRCRAFT CATAPULT VESSEL CATAPULT ARMED MERCHANTMAN AMPHIBIOUS VEHICLE BLOCK SHIP BOARDING BOAT CABLE LAYER CRAFT CANOE CATAMARAN COBLE FOYBOAT CORACLE GIG HOVERCRAFT HYDROFOIL LOGBOAT SCHUIT SEWN BOAT SHIPS BOAT DINGHY CUSTOMS AND EXCISE VESSEL COASTGUARD VESSEL REVENUE CUTTER CUSTOMS BOAT PREVENTIVE SERVICE VESSEL REVENUE CUTTER DREDGER BUCKET DREDGER GRAB DREDGER HOPPER DREDGER OYSTER DREDGER SUCTION DREDGER EXPERIMENTAL CRAFT FACTORY SHIP WHALE PROCESSING SHIP FISHING VESSEL BANKER DRIFTER FIVE MAN BOAT HOVELLER LANCASHIRE NOBBY OYSTER DREDGER SEINER SKIFF TERRE NEUVA TRAWLER WHALER WHALE CATCHER GALLEY HOUSE BOAT HOVELLER HULK COAL HULK PRISON HULK 2 MARITIME CRAFT CLASS LIST SHEER HULK STORAGE HULK GRAIN HULK POWDER HULK LAUNCH LEISURE CRAFT CABIN CRAFT CABIN CRUISER DINGHY RACING CRAFT SKIFF YACHT LONG BOAT LUG BOAT MOTOR LAUNCH MULBERRY HARBOUR BOMBARDON INTERMEDIATE PIERHEAD PONTOON PHOENIX CAISSON WHALE UNIT BEETLE UNIT NAVAL SUPPORT VESSEL ADMIRALTY VESSEL ADVICE BOAT BARRAGE BALLOON VESSEL BOOM DEFENCE VESSEL DECOY VESSEL DUMMY WARSHIP Q SHIP DEGAUSSING VESSEL DEPOT SHIP DISTILLING SHIP EXAMINATION SERVICE VESSEL FISHERIES PROTECTION VESSEL FLEET MESSENGER HOSPITAL SHIP MINE CARRIER OILER ORDNANCE SHIP ORDNANCE SLOOP STORESHIP SUBMARINE TENDER TARGET CRAFT TENDER BOMB SCOW DINGHY TORPEDO RECOVERY VESSEL TROOP SHIP VICTUALLER PADDLE STEAMER PATROL VESSEL -

Spencer Walker Dell Martin

SPENCER WALKER 28 DELL MARTIN LGY#829 RATED US T | $3.99 0 2 8 1 1 7 5 9 6 0 6 0 8 9 3 6 9 BONUS DIGITAL EDITION – DETAILS INSIDE! PETER PARKER was bitten by a radioactive spider and gained the proportional speed, strength and agility of a SPIDER, adhesive fingertips and toes, and the unique precognitive awareness of danger called “SPIDER-SENSE”! After the tragic death of his Uncle Ben, Peter understood that with great power there must also come great responsibility. He became the crimefighting super hero called… WHO RUN THE WORLD? Part Three The SYNDICATE is a new criminal cooperative composed of Beetle, White Rabbit, Scorpia, Electro, Trapstr, and Doctor Octopus (sometimes called Lady Octopus). They’re scoffing at the law and the patriarchy, and they just busted into the F.E.A.S.T. center (where Peter Parker’s Aunt May and roommate Randy Robertson work) to kidnap Pete’s other roommate, Boomerang! Lucky for Boomerang (Fred), he was probably still wearing a Spider-Tracer, so Spider-Man just needs to check the long-range receiver in his apartment to find Fred. On the roof crawling to his own window, Spidey passed over Randy’s skylight and couldn’t help but notice HE WAS MAKING OUT WITH BEETLE. NICK SPENCER JOHN DELL | inker LAURA MARTIN and ANDREW CROSSLEY | colorists writer VC’S JOE CARAMAGNA | letterer RYAN OTTLEY and NATHAN FAIRBAIRN | cover artists ANTHONY GAMBINO | designer KATHLEEN WISNESKI | assistant editor NICK LOWE | editor C.B. CEBULSKI | editor in chief JOE QUESADA | chief creative officer KEV WALKER DAN BUCKLEY | president ALAN FINE | executive producer penciler SPIDER-MAN created by STAN LEE and STEVE DITKO THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN No. -

Conservation of Energy, Individual Agency, and Gothic Terror in Richard Marsh’S the Beetle,Or, What’S Scarier Than an Ancient, Evil, Shape-Shifting Bug?

Victorian Literature and Culture (2011), 39, 65–85. C Cambridge University Press 2010. 1060-1503/10 $15.00 doi:10.1017/S1060150310000276 CONSERVATION OF ENERGY, INDIVIDUAL AGENCY, AND GOTHIC TERROR IN RICHARD MARSH’S THE BEETLE,OR, WHAT’S SCARIER THAN AN ANCIENT, EVIL, SHAPE-SHIFTING BUG? By Anna Maria Jones I went into my laboratory to plan murder – legalised murder – on the biggest scale it ever has been planned. I was on the track of a weapon which would make war not only an affair of a single campaign, but of a single half-hour. It would not want an army to work it either. Once let an individual, or two or three at most, in possession of my weapon-that-was-to-be, get within a mile or so of even the largest body of disciplined troops that ever yet a nation put into the field, and – pouf! – in about the time it takes you to say that they would be all dead men. —Marsh, The Beetle, chapter 12 THERE IS A FAMILIAR CRITICAL NARRATIVE about the fin de siecle,` into which gothic fiction fits very neatly. It is the story of the gradual decay of Victorian values, especially their faith in progress and in the empire. The self-satisfied (middle-class) builders of empire were superseded by the doubters and decadents. As Patrick Brantlinger writes, “After the mid- Victorian years the British found it increasingly difficult to think of themselves as inevitably progressive; they began worrying instead about the degeneration of their institutions, their culture, their racial ‘stock’” (230).1 And this late-Victorian anomie expressed itself in the move away from realism and toward romance, decadence, naturalism, and especially gothic horror. -

Sacks • Checchetto • Mossa 10

SACKS • CHECCHETTO • MOSSA 10 PARENTAL ADVISORY $3.99US 0 1 0 1 1 7 5 9 6 0 6 0 8 8 3 6 2 BONUS DIGITAL EDITION – DETAILS INSIDE! FORTY-FIVE YEARS AGO, THE WORLD’S SUPER VILLAINS ORGANIZED UNDER THE RED SKULL AND COLLECTIVELY WIPED OUT NEARLY ALL OF THE SUPER HEROES. FEW SURVIVED THE CARNAGE THAT FATEFUL DAY, AND NONE OF THEM UNSCATHED. THE UNITED STATES WAS DIVIDED UP INTO TERRITORIES CONTROLLED BY THE VILLAINS, AND THE GOOD PEOPLE SURVIVE IN THESE WASTELANDS AS BEST THEY CAN. AMONG THEM LIVES A FORMER HERO WHO’S GIVEN UP ON THAT WAY OF LIFE. HE IS CLINT BARTON, BUT SOME KNOW HIM AS… AN EYE FOR AN EYE PART 10 BLOOD FROM A STONE CLINT BARTON IS GOING BLIND. HE WANTS TO SEE THROUGH ONE FINAL MISSION — EXACTING REVENGE ON HIS FORMER THUNDERBOLTS COLLEAGUES THAT HELPED BRING ABOUT THE DEATHS OF THE AVENGERS— BEFORE HE LOSES HIS SIGHT FOR GOOD. HE’S TAKEN OUT ATLAS AND THE BEETLE, AND AFTER SUFFERING AN INJURY, TURNED TO FORMER CO-HAWKEYE KATE BISHOP TO HELP HIM COMPLETE HIS QUEST. IN HOPES OF REDEMPTION, BEFORE SHE DIED, EX-THUNDERBOLT SONGBIRD GAVE CLINT A MAP LEADING TO MOONSTONE, ANOTHER FORMER TEAMMATE. HOWEVER, THEY’LL HAVE TO MOVE QUICKER NOW THAT THE MARSHAL BULLSEYE SET HIS SIGHTS FIRMLY ON THE HAWKEYES… WRITER... ETHAN SACKS ARTIST... MARCO CHECCHETTO COLORIST... ANDRES MOSSA LETTERER... VC’s JOE CARAMAGNA COVER ARTIST... MARCO CHECCHETTO LOGO DESIGN... ADAM DEL RE GRAPHIC DESIGN... ANTHONY GAMBINO EDITOR... MARK BASSO EDITOR IN CHIEF... C.B. -

Gothic Fiction, Mental Science and the Fin-De-Siècle Discourse Of

Disintegrated Subjects: Gothic Fiction, Mental Science and the fin-de-siècle Discourse of Dissociation by Natasha L. Rebry B.A., Wilfrid Laurier University, 2003 M.A., Wilfrid Laurier University, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctorate of Philosophy in THE COLLEGE OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Interdisciplinary Studies) [English/History of Psychology] THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Okanagan) March 2013 © Natasha L. Rebry, 2013 ii Abstract The end of the nineteenth century witnessed a rise in popularity of Gothic fiction, which included the publication of works such as Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), George Du Maurier’s Trilby (1894), Arthur Machen’s The Great God Pan (1894) and The Three Impostors (1895), and Richard Marsh’s The Beetle (1897), featuring menacing foreign mesmerists, hypnotising villains, somnambulistic criminals and spectacular dissociations of personality. Such figures and tropes were not merely the stuff of Gothic fiction, however; from 1875 to the close of the century, cases of dual or multiple personality were reported with increasing frequency, and dissociation – a splitting off of certain mental processes from conscious awareness – was a topic widely discussed in Victorian medical, scientific, social, legal and literary circles. Cases of dissociation and studies of dissociogenic practices like mesmerism and hypnotism compelled attention as they seemed to indicate the fragmented, porous and malleable nature of the human mind and will, challenging longstanding beliefs in a unified soul or mind governing human action. Figured as plebeian, feminine, degenerative and “primitive” in a number of discourses related to mental science, dissociative phenomena offered a number of rich metaphoric possibilities for writers of Gothic fiction. -

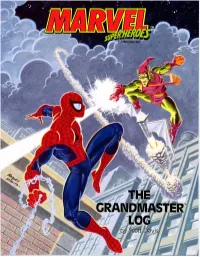

TSR6907.MHR2.Webs-Th

WEBS: The SPIDER-MAN Dossier The GRANDMASTER Log by Scott Davis Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 GRANDMASTER Log Entries …………………………………………………………………………... 3 SPIDER-MAN ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 SPIDER-MAN Supporting Cast ……………………………………………………………………………. 7 SPIDER-MAN Allies ……………………………………………………………………………………… 10 SPIDER-MAN Foes ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 18 An Adventurous Week …………………………………………………………………………………… 56 Set-up ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 56 Timelines …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 58 Future Storyline Tips ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 64 Credits: Design: Scott Davis Art Coordination: Peggy Cooper Editing: Dale A. Donovan Typography: Tracey Zamagne Cover Art: Mark Bagley & John Romita Cartography: Steven Sullivan Interior & Foldup Art: The Marvel Bullpen Design & Production: Paul Hanchette This book is protected under the copyright law of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc. and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. The names of the characters used herein are fictitious and do not refer to any persons living or dead. Any descriptions including similarities to persons living or dead are merely coincidental. Random House and its affiliate companies have worldwide distribution rights in the book trade for English language products of TSR, Inc. Distributed to the book and hobby trade in the United Kingdom by TSR Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL UNIVERSE are trademarks of Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All Marvel characters, character names, and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. 1992 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All Rights Reserved. The TSR logo is a trademark owned by TSR, Inc. 1992 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. TSR, Inc.