An Examination of Superhero Tropes in My Hero Academia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Graphic Novels for Children and Teens

J/YA Graphic Novel Titles The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation Sid Jacobson Hill & Wang Gr. 9+ Age of Bronze, Volume 1: A Thousand Ships Eric Shanower Image Comics Gr. 9+ The Amazing “True” Story of a Teenage Single Mom Katherine Arnoldi Hyperion Gr. 9+ American Born Chinese Gene Yang First Second Gr. 7+ American Splendor Harvey Pekar Vertigo Gr. 10+ Amy Unbounded: Belondweg Blossoming Rachel Hartman Pug House Press Gr. 3+ The Arrival Shaun Tan A.A. Levine Gr. 6+ Astonishing X-Men Joss Whedon Marvel Gr. 9+ Astro City: Life in the Big City Kurt Busiek DC Comics Gr. 10+ Babymouse Holm, Jennifer Random House Children’s Gr. 1-5 Baby-Sitter’s Club Graphix (nos. 1-4) Ann M. Martin & Raina Telgemeier Scholastic Gr. 3-7 Barefoot Gen, Volume 1: A Cartoon Story of Hiroshima Keiji Nakazawa Last Gasp Gr. 9+ Beowulf (graphic adaptation of epic poem) Gareth Hinds Candlewick Press Gr. 7+ Berlin: City of Stones Berlin: City of Smoke Jason Lutes Drawn & Quarterly Gr. 9+ Blankets Craig Thompson Top Shelf Gr. 10+ Bluesman (vols. 1, 2, & 3) Rob Vollmar NBM Publishing Gr. 10+ Bone Jeff Smith Cartoon Books Gr. 3+ Breaking Up: a Fashion High graphic novel Aimee Friedman Graphix Gr. 5+ Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Season 8) Joss Whedon Dark Horse Gr. 7+ Castle Waiting Linda Medley Fantagraphics Gr. 5+ Chiggers Hope Larson Aladdin Mix Gr. 5-9 Cirque du Freak: the Manga Darren Shan Yen Press Gr. 7+ City of Light, City of Dark: A Comic Book Novel Avi Orchard Books Gr. -

The Rat Pack and the British Pierrot

THE RAT PACK AND THE BRITISH PIERROT: NEGOTIATIONS OF NATIONAL IDENTITY, ALIENATION AND BELONGING IN THE AESTHETICS AND INFLUENCES OF CONCERTED TROUPES IN POPULAR ENTERTAINMENT. DAVE CALVERT A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Research The University of Huddersfield January 2013 Abstract The thesis below consists of an introduction followed by three chapters that reflect on the performance work of two distinct forms, the British Pierrot troupe and the Rat Pack. The former is a model of performance adopted and adapted by several hundred companies around the British coastline in the first half of the twentieth century. The latter is an exclusive collaboration between five performers with celebrated individual careers in post-World War Two America. Both are indebted to the rise of blackface minstrelsy, and the subsequent traditions of variety or vaudeville performance. Both are also concerned with matters of national unity, alienation and belonging. The Introduction will expand on the two forms, and the similarities and differences between them. While these broad similarities lend a thematic framework to the thesis, the distinctions are marked and specific. Accordingly, the chapters are discrete and do not directly inform or refer to each other. Chapter One considers the emergence of the Pierrot troupe from a historical European aesthetic and argues that despite references to earlier Italian and French modes of performance, the innovations of the new form situate the British Pierrot in its contemporary and domestic context. Chapter Two explores this context in more detail, and looks at the Pierrot’s place in a symbolic network that encompasses royal imagery and identity, the racial implications of blackface minstrelsy and the carnivalesque liminality of the seaside. -

Queer Here: Poetry to Comic Emma Lennen Katie Jan

Queer Here: Poetry to Comic Emma Lennen Katie Jan Pull Quote: “For the new audience of queer teenagers, the difference between the public and the superhero resonates with them because they feel different from the rest of society.” Consider this: a superhero webcomic. Now consider this: a queer superhero webcomic. If you are anything like me, you were infinitely more elated at the second choice, despite how much you enjoy the first. I love reading queer webcomics because by being online, they bypass publishers who may shoot them down for their queerness. As a result, they manage to elude the systematic repression of the LGBTQA+ community. In the 1950s, when repression of the community was even more prevalent, Frank O’Hara wrote the poem “Homosexuality” to express his journey of acceptance as well as to give advice to future gay people. The changes I made in my translation of the poem “Homosexuality” into a modern webcomic demonstrate the different time periods’ expectations of queer content, while still telling the same story with the same purpose, just in a different genre. Despite the difference between the genres, the first two lines and the copious amount of imagery present in the poem allowed for some near-direct translation. The poem begins with “So we are taking off our masks, are we, and keeping / our mouths shut? As if we’d been pierced by a glance!” (O’Hara 1-2). While usually masks symbolize hiding your true self and therefore have a negative connotation, the poem instead considers it one’s pride. Similarly, for many superheroes, the mask does not represent shame, it represents power and responsibility. -

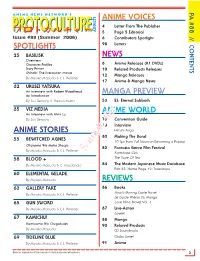

Protoculture Addicts

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

Manga Book Club Handbook

MANGA BOOK CLUB HANDBOOK Starting and making the most of book clubs for manga! STAFF COMIC Director’sBOOK LEGAL Note Charles Brownstein, Executive Director DEFENSE FUND Alex Cox, Deputy Director Everything is changing in 2016, yet the familiar challenges of the past continueBetsy to Gomez, Editorial Director reverberate with great force. This isn’t just true in the broader world, but in comics,Maren Williams, Contributing Editor Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor too. While the boundaries defining representation and content in free expression are protectingexpanding, wethe continue freedom to see to biasedread comics!or outmoded Our viewpoints work protects stifling those advances.Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel readers, creators, librarians, retailers, publishers, and educa- STAFF As you’ll see in this issue of CBLDF Defender, we are working on both ends of the Charles Brownstein, Executive Director torsspectrum who byface providing the threat vital educationof censorship. about the We people monitor whose worklegislation expanded free exBOARD- Alex OF Cox, DIRECTORS Deputy Director pression while simultaneously fighting all attempts to censor creative work in comics.Larry Marder,Betsy Gomez, President Editorial Director and challenge laws that would limit the First Amendment. Maren Williams, Contributing Editor In this issue, we work the former end of the spectrum with a pair of articles spotlightMilton- Griepp, Vice President We create resources that promote understanding of com- Jeff Abraham,Caitlin McCabe,Treasurer Contributing Editor ing the pioneers who advanced diverse content. On page 10, “Profiles in Black Cartoon- Dale Cendali,Robert SecretaryCorn-Revere, Legal Counsel icsing” and introduces the rights you toour some community of the cartoonists is guaranteed. -

Meilyne Tran BOOK WALKER Co.Ltd. [email protected] Ph: +81-3-5216-8312

MEDIA CONTACT: Meilyne Tran BOOK WALKER Co.Ltd. [email protected] Ph: +81-3-5216-8312 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BOOK☆WALKER CELEBRATES ANIME BOSTON WITH GIVEAWAYS, NEW TITLES KADOKAWA's Online Store for Manga & Light Novels MARCH 15, 2016 – BookWalker returns to N. America with its first anime con appearance of 2016 at Anime Boston. Anime Boston will be held on March 25-27 at the Hynes Convention Center in Boston, Massachusetts. Manga and light novel readers, visit booth #308 for your chance to win prizes, like Sword Art Online, Fate/ and Kill La Kill figures, limited edition Sword Art Online clear file folders, or a $10 gift card good toward purchasing any digital manga or light novel title on BookWalker Global. WIN PRIZES FROM BOOKWALKER AT ANIME BOSTON There are several ways to win! If you’re new to BookWalker, just visit http://global.bookwalker.jp and subscribe to our mailing list. Show your “My Account” page to BookWalker booth staff at Anime Boston, and you’ll get a chance to try for one of the prizes. For a second chance to win, use your $10 gift card to purchase any eBook on BookWalker. Want another chance to take home a prize? Take a photo at the BookWalker booth, follow BookWalker on Twitter at @BOOKWALKER_GL and post your photo on Twitter with the hashtags #AnimeBoston and #BOOKWALKER. Show your tweet to BookWalker booth staff, and you’ll get a chance to win one of three Neon Genesis Evangelion figures. Haven’t tried BookWalker yet? Anime Boston is also your chance to get a hands-on look at our eBook store. -

11Eyes Achannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air

11eyes AChannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air Master Amaenaideyo Angel Beats Angelic Layer Another Ao No Exorcist Appleseed XIII Aquarion Arakawa Under The Bridge Argento Soma Asobi no Iku yo Astarotte no Omocha Asu no Yoichi Asura Cryin' B Gata H Kei Baka to Test Bakemonogatari (and sequels) Baki the Grappler Bakugan Bamboo Blade Banner of Stars Basquash BASToF Syndrome Battle Girls: Time Paradox Beelzebub BenTo Betterman Big O Binbougami ga Black Blood Brothers Black Cat Black Lagoon Blassreiter Blood Lad Blood+ Bludgeoning Angel Dokurochan Blue Drop Bobobo Boku wa Tomodachi Sukunai Brave 10 Btooom Burst Angel Busou Renkin Busou Shinki C3 Campione Cardfight Vanguard Casshern Sins Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Chaos;Head Chobits Chrome Shelled Regios Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai Clannad Claymore Code Geass Cowboy Bebop Coyote Ragtime Show Cuticle Tantei Inaba DFrag Dakara Boku wa, H ga Dekinai Dan Doh Dance in the Vampire Bund Danganronpa Danshi Koukousei no Nichijou Daphne in the Brilliant Blue Darker Than Black Date A Live Deadman Wonderland DearS Death Note Dennou Coil Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko Densetsu no Yuusha no Densetsu Desert Punk Detroit Metal City Devil May Cry Devil Survivor 2 Diabolik Lovers Disgaea Dna2 Dokkoida Dog Days Dororon EnmaKun Meeramera Ebiten Eden of the East Elemental Gelade Elfen Lied Eureka 7 Eureka 7 AO Excel Saga Eyeshield 21 Fight Ippatsu! JuudenChan Fooly Cooly Fruits Basket Full Metal Alchemist Full Metal Panic Futari Milky Holmes GaRei Zero Gatchaman Crowds Genshiken Getbackers Ghost -

Club Add 2 Page Designoct07.Pub

H M. ADVS. HULK V. 1 collects #1-4, $7 H M. ADVS FF V. 7 SILVER SURFER collects #25-28, $7 H IRR. ANT-MAN V. 2 DIGEST collects #7-12,, $10 H POWERS DEF. HC V. 2 H ULT FF V. 9 SILVER SURFER collects #12-24, $30 collects #42-46, $14 H C RIMINAL V. 2 LAWLESS H ULTIMATE VISON TP collects #6-10, $15 collects #0-5, $15 H SPIDEY FAMILY UNTOLD TALES H UNCLE X-MEN EXTREMISTS collects Spidey Family $5 collects #487-491, $14 Cut (Original Graphic Novel) H AVENGERS BIZARRE ADVS H X-MEN MARAUDERS TP The latest addition to the Dark Horse horror line is this chilling OGN from writer and collects Marvel Advs. Avengers, $5 collects #200-204, $15 Mike Richardson (The Secret). 20-something Meagan Walters regains consciousness H H NEW X-MEN v5 and finds herself locked in an empty room of an old house. She's bleeding from the IRON MAN HULK back of her head, and has no memory of where the wound came from-she'd been at a collects Marvel Advs.. Hulk & Tony , $5 collects #37-43, $18 club with some friends . left angrily . was she abducted? H SPIDEY BLACK COSTUME H NEW EXCALIBUR V. 3 ETERNITY collects Back in Black $5 collects #16-24, $25 (on-going) H The End League H X-MEN 1ST CLASS TOMORROW NOVA V. 1 ANNIHILATION A thematic merging of The Lord of the Rings and Watchmen, The End League follows collects #1-8, $5 collects #1-7, $18 a cast of the last remaining supermen and women as they embark on a desperate and H SPIDEY POWER PACK H HEROES FOR HIRE V. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Understanding Manga, Comics and Graphic Novels. Dr Mel

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northumbria Research Link ‘So what is this mango, anyway?’ Understanding manga, comics and graphic novels. Dr Mel Gibson. Literacy Consultant and Senior Lecturer, University of Northumbria. Graphic novels, comics and manga can play an important part in encouraging reading for pleasure amongst students of any age and also have a role in teaching in many subject areas. I’m going to offer a small snapshot of the least well known of these, manga, below, but want to start with a few general points about the comic strip medium. Graphic novels, comics and manga are often seen as texts specifically for younger male reluctant readers, but such an assumption underestimates this enormously flexible medium, as it can be used to create complex works of fiction or non-fiction for adults and young adults, male and female, as well as humourous stories for the very young. The comic strip has been used to create a range of work that encompasses the superb Alice in Sunderland, by British creator Bryan Talbot, which explores memory, history and the nature of narrative, drawing on poetry, plays and novels, as well as other comics from around the world, as well as the slapstick humour of The Beano, with it’s cross-generational appeal and playful approach to language and image. It also includes television spin-offs, most notably, perhaps, The Simpsons and Futurama, which offer clever, witty takes on family, relationships and media, as well as genres that have generated spin-offs in other media, like superhero comics, themselves capable of addressing a huge range of ages and abilities. -

Chapter 3 Heroines in a Time of War: Nelvana of the Northern Lights And

Chapter 3 Heroines in a Time of War: Nelvana of the Northern Lights and Wonder Woman as Symbols of the United States and Canada Scores of superheroes emerged in comic books just in time to defend the United States and Canada from the evil machinations of super-villains, Hitler, Mussolini, and other World War II era enemies. By 1941, War Nurse Pat Parker, Miss America, Pat Patriot, and Miss Victory were but a few of the patriotic female characters who had appeared in comics to fight villains and promote the war effort. These characters had all but disappeared by 1946, a testament to their limited wartime relevance. Though Nelvana of the Northern Lights (hereafter “Nelvana”) and Wonder Woman first appeared alongside the others in 1941, they have proven to be more enduring superheroes than their crime-fighting colleagues. In particular, Nelvana was one of five comic book characters depicted in the 1995 Canada Post Comic Book Stamp Collection, and Wonder Woman was one of ten DC Comics superheroes featured in the 2006 United States Postal Service (USPS) Commemorative Stamp Series. The uniquely enduring iconic statuses of Nelvana and Wonder Woman result from their adventures and character development in the context of World War II and the political, social, and cultural climates in their respective English-speaking areas of North America. Through a comparative analysis of Wonder Woman and Nelvana, two of their 1942 adventures, and their subsequent deployment through government-issued postage stamps, I will demonstrate how the two characters embody and reinforce what Michael Billig terms “banal nationalism” in their respective national contexts.