Indo Aryan Languages)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Ethnicity, Education and Equality in Nepal

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 36 Number 2 Article 6 December 2016 New Languages of Schooling: Ethnicity, Education and Equality in Nepal Uma Pradhan University of Oxford, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Pradhan, Uma. 2016. New Languages of Schooling: Ethnicity, Education and Equality in Nepal. HIMALAYA 36(2). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol36/iss2/6 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New Languages of Schooling: Ethnicity, Education, and Equality in Nepal Uma Pradhan Mother tongue education has remained this attempt to seek membership into a controversial issue in Nepal. Scholars, multiple groups and display of apparently activists, and policy-makers have favored contradictory dynamics. On the one hand, the mother tongue education from the standpoint practices in these schools display inward- of social justice. Against these views, others looking characteristics through the everyday have identified this effort as predominantly use of mother tongue, the construction of groupist in its orientation and not helpful unified ethnic identity, and cultural practices. in imagining a unified national community. On the other hand, outward-looking dynamics Taking this contention as a point of inquiry, of making claims in the universal spaces of this paper explores the contested space of national education and public places could mother tongue education to understand the also be seen. -

Honorificity, Indexicality and Their Interaction in Magahi

SPEAKER AND ADDRESSEE IN NATURAL LANGUAGE: HONORIFICITY, INDEXICALITY AND THEIR INTERACTION IN MAGAHI BY DEEPAK ALOK A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Linguistics Written under the direction of Mark Baker and Veneeta Dayal and approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Speaker and Addressee in Natural Language: Honorificity, Indexicality and their Interaction in Magahi By Deepak Alok Dissertation Director: Mark Baker and Veneeta Dayal Natural language uses first and second person pronouns to refer to the speaker and addressee. This dissertation takes as its starting point the view that speaker and addressee are also implicated in sentences that do not have such pronouns (Speas and Tenny 2003). It investigates two linguistic phenomena: honorification and indexical shift, and the interactions between them, andshow that these discourse participants have an important role to play. The investigation is based on Magahi, an Eastern Indo-Aryan language spoken mainly in the state of Bihar (India), where these phenomena manifest themselves in ways not previously attested in the literature. The phenomena are analyzed based on the native speaker judgements of the author along with judgements of one more native speaker, and sometimes with others as the occasion has presented itself. Magahi shows a rich honorification system (the encoding of “social status” in grammar) along several interrelated dimensions. Not only 2nd person pronouns but 3rd person pronouns also morphologically mark the honorificity of the referent with respect to the speaker. -

Multilingual Education and Nepal Appendix 3

19. Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove and Mohanty, Ajit. Policy and Strategy for MLE in Nepal Report by Tove Skutnabb-Kangas and Ajit Mohanty Consultancy visit 4-14 March 2009i Sanothimi, Bhaktapur: Multilingual Education Program for All Non-Nepali Speaking Students of Primary Schools of Nepal. Ministry of Education, Department of Education, Inclusive Section. See also In Press, for an updated version. List of Contents List of Contents List of Appendices List of Tables List of Figures List of Abbreviations 1. Introduction: placing language in education issues in Nepal in a broader societal, economic and political framework 2. Broader Language Policy and Planning Perspectives and Issues 2.1. STEP 1 in Language Policy and Language Planning: Broad-based political debates about the goals of language 2.2. STEP 2 in Educational Language Policy and Language Planning: Realistic language proficiency goal/aim in relation to the baseline 2.3. STEP 3 in Educational Language Planning: ideal goals and prerequisites compared with characteristics of present schools 2.4. STEP 4 in Educational Language Planning: what has characterized programmes with high versus low success? 2.5. STEP 5 in Educational Language Planning: does it pay off to maintain ITM languages? 3. Scenarios 3.1. Introduction 3.2. Models with often harmful results: dominant-language-medium (subtractive assimilatory submersion) 3.3. Somewhat better but not good enough results: early-exit transitional models 3.4. Even better results: late-exit transitional models 3.5. Strongest form: self-evident mother tongue medium models with no transition 4. Experiences from Nepal: the situation today 5. Specific challenges in Nepal: implementation strategies 5.1. -

Minority Languages in India

Thomas Benedikter Minority Languages in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India ---------------------------- EURASIA-Net Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues 2 Linguistic minorities in India An appraisal of the linguistic rights of minorities in India Bozen/Bolzano, March 2013 This study was originally written for the European Academy of Bolzano/Bozen (EURAC), Institute for Minority Rights, in the frame of the project Europe-South Asia Exchange on Supranational (Regional) Policies and Instruments for the Promotion of Human Rights and the Management of Minority Issues (EURASIA-Net). The publication is based on extensive research in eight Indian States, with the support of the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano and the Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata. EURASIA-Net Partners Accademia Europea Bolzano/Europäische Akademie Bozen (EURAC) – Bolzano/Bozen (Italy) Brunel University – West London (UK) Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität – Frankfurt am Main (Germany) Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group (India) South Asian Forum for Human Rights (Nepal) Democratic Commission of Human Development (Pakistan), and University of Dhaka (Bangladesh) Edited by © Thomas Benedikter 2013 Rights and permissions Copying and/or transmitting parts of this work without prior permission, may be a violation of applicable law. The publishers encourage dissemination of this publication and would be happy to grant permission. -

The Tatoeba Translation Challenge--Realistic Data Sets For

The Tatoeba Translation Challenge – Realistic Data Sets for Low Resource and Multilingual MT Jorg¨ Tiedemann University of Helsinki [email protected] https://github.com/Helsinki-NLP/Tatoeba-Challenge Abstract most important point is to get away from artificial This paper describes the development of a new setups that only simulate low-resource scenarios or benchmark for machine translation that pro- zero-shot translations. A lot of research is tested vides training and test data for thousands of with multi-parallel data sets and high resource lan- language pairs covering over 500 languages guages using data sets such as WIT3 (Cettolo et al., and tools for creating state-of-the-art transla- 2012) or Europarl (Koehn, 2005) simply reducing tion models from that collection. The main or taking away one language pair for arguing about goal is to trigger the development of open the capabilities of learning translation with little or translation tools and models with a much without explicit training data for the language pair broader coverage of the World’s languages. Using the package it is possible to work on in question (see, e.g., Firat et al.(2016a,b); Ha et al. realistic low-resource scenarios avoiding arti- (2016); Lakew et al.(2018)). Such a setup is, how- ficially reduced setups that are common when ever, not realistic and most probably over-estimates demonstrating zero-shot or few-shot learning. the ability of transfer learning making claims that For the first time, this package provides a do not necessarily carry over towards real-world comprehensive collection of diverse data sets tasks. -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

The Maulana Who Loved Krishna

SPECIAL ARTICLE The Maulana Who Loved Krishna C M Naim This article reproduces, with English translations, the e was a true maverick. In 1908, when he was 20, he devotional poems written to the god Krishna by a published an anonymous article in his modest Urdu journal Urd -i-Mu’all (Aligarh) – circulation 500 – maulana who was an active participant in the cultural, H ū ā which severely criticised the British colonial policy in Egypt political and theological life of late colonial north India. regarding public education. The Indian authorities promptly Through this, the article gives a glimpse of an Islamicate charged him with “sedition”, and demanded the disclosure of literary and spiritual world which revelled in syncretism the author’s name. He, however, took sole responsibility for what appeared in his journal and, consequently, spent a little with its surrounding Hindu worlds; and which is under over one year in rigorous imprisonment – held as a “C” class threat of obliteration, even as a memory, in the singular prisoner he had to hand-grind, jointly with another prisoner, world of globalised Islam of the 21st century. one maund (37.3 kgs) of corn every day. The authorities also confi scated his printing press and his lovingly put together library that contained many precious manuscripts. In 1920, when the fi rst Indian Communist Conference was held at Kanpur, he was one of the organising hosts and pre- sented the welcome address. Some believe that it was on that occasion he gave India the slogan Inqilāb Zindabād as the equivalent to the international war cry of radicals: “Vive la Revolution” (Long Live The Revolution). -

Neo-Vernacularization of South Asian Languages

LLanguageanguage EEndangermentndangerment andand PPreservationreservation inin SSouthouth AAsiasia ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 7 Language Endangerment and Preservation in South Asia ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 7 PUBLISHED AS A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION LANGUAGE ENDANGERMENT AND PRESERVATION IN SOUTH ASIA Special Publication No. 7 (January 2014) ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 USA http:/nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I PRESS 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822-1888 USA © All text and images are copyright to the authors, 2014 Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives License ISBN 978-0-9856211-4-8 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4607 Contents Contributors iii Foreword 1 Hugo C. Cardoso 1 Death by other means: Neo-vernacularization of South Asian 3 languages E. Annamalai 2 Majority language death 19 Liudmila V. Khokhlova 3 Ahom and Tangsa: Case studies of language maintenance and 46 loss in North East India Stephen Morey 4 Script as a potential demarcator and stabilizer of languages in 78 South Asia Carmen Brandt 5 The lifecycle of Sri Lanka Malay 100 Umberto Ansaldo & Lisa Lim LANGUAGE ENDANGERMENT AND PRESERVATION IN SOUTH ASIA iii CONTRIBUTORS E. ANNAMALAI ([email protected]) is director emeritus of the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore (India). He was chair of Terralingua, a non-profit organization to promote bi-cultural diversity and a panel member of the Endangered Languages Documentation Project, London. -

The Forms of Seeking Accepting and Denying Permissions in English and Awadhi Language

THE FORMS OF SEEKING ACCEPTING AND DENYING PERMISSIONS IN ENGLISH AND AWADHI LANGUAGE A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English Education In Partial Fulfilment for the Masters of Education in English Submitted by Jyoti Kaushal Faculty of Education Tribhuwan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu, Nepal 2018 THE FORMS OF SEEKING ACCEPTING AND DENYING PERMISSIONS IN ENGLISH AND AWADHI LANGUAGE A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English Education In Partial Fulfilment for the Masters of Education in English Submitted by Jyoti Kaushal Faculty of Education Tribhuwan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu, Nepal 2018 T.U. Reg. No.:9-2-540-164-2010 Date of Approval Thesis Fourth Semester Examination Proposal: 18/12/2017 Exam Roll No.: 28710094/072 Date of Submission: 30/05/2018 DECLARATION I hereby declare that to the best of my knowledge this thesis is original; no part of it was earlier submitted for the candidate of research degree to any university. Date: ..…………………… Jyoti Kaushal i RECOMMENDATION FOR ACCEPTANCE This is to certify that Miss Jyoti Kaushal has prepared this thesis entitled The Forms of Seeking, Accepting and Denying Permissions in English and Awadhi Language under my guidance and supervision I recommend this thesis for acceptance Date: ………………………… Mr. Raj Narayan Yadav Reader Department of English Education Faculty of Education TU, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal ii APPROVAL FOR THE RESEARCH This thesis has been recommended for evaluation from the following Research Guidance Committee: Signature Dr. Prem Phyak _______________ Lecturer & Head Chairperson Department of English Education University Campus T.U., Kirtipur, Mr. Raj Narayan Yadav (Supervisor) _______________ Reader Member Department of English Education University Campus T.U., Kirtipur, Mr. -

Interference of Bhojpuri Language in Learning English As a Second Language

ELT VOICES – INDIA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR TEACHERS OF ENGLISH FEBRUARY 2014 | VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 | ISSN 2230-9136 (PRINT) 2321-7170 (ONLINE) Interference of Bhojpuri Language in Learning English as a Second Language V. RADHIKA1 ABSTRACT Studying the special features of any language is interesting for exploring many unrevealed facts about that language. The purpose of this paper is to create interest in the mind of readers to identify the special features of Bhojpuri language, which is gaining importance in India in the recent years among the spoken languages and make the readers to get rid of the problem of interference of this language in learning English as a second language. 1. Assistant Professor in English, AVIT, VMU, Paiyanoor, India. ELT VOICES – INDIA February 2014 | Volume 4, Issue 1 1. Introduction The paper proposes to make an in-depth study of Bhojpuri language to enable learners to compare and contrast between two languages, Bhojpuri and English by which communicative skill in English can be properly perceived. Bhojpuri language has its own phonological and morphological pattern. The present study is concerned with tracing the difference between two languages (i.e.) English and Bhojpuri, with reference to their grammatical structure and its relevant information. Aim of the Paper Create interest in the mind of scholars to make the detailed study about the Bhojpuri language with reference to their grammar pattern and to find out possible solution to eliminate the problem of mother tongue interference. 2. Origin of Bhojpuri Language Bhojpuri language gets its name from a place called ‘Bhojpur’ in Bihar. It is believed that Ujjain Rajputs claimed their descent from Raja Bhoj of Malwa in the sixteenth century. -

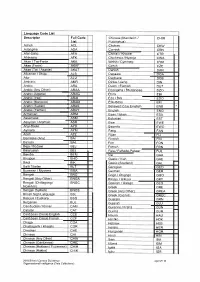

Language Code List Descriptor Full Code List Acholi ACL Adangme

Language Code List Descriptor Full Code Chinese (Mandarin I CHIM List Putonqhua) Acholi ACL Chokwe CKW Adangme ADA Cornish CRN Afar-Saha AFA Chitrali I Khowar CTR Afrikaans AFK Chichewa I Nyanja CWA Akan I Twi-Fante AKA Welsh I Cymraeg CYM Akan (Fante) AKAF Czech CZE Akan (Twi I Asante) AKAT Danish DAN Albanian I Shqip ALB Dagaare DGA Alur ALU Dagbane DGB Amharic AMR Dinka I Jieng DIN Arabic ARA Dutch I Flemish OUT Arabic (Any Other) ARAA Dzongkha I Bhutanese DZO Arabic (Algeria) ARAG Ebira EBI Arabic (Iraq) ARAI Eda I Bini EDO Arabic (Morocco) ARAM Efik-lbibio EFI Arabic (Sudan) ARAS Believed to be English ENB * Arabic (Yemen) ARAY English ENG * Armenian ARM Esan / lshan ESA Assamese ASM Estonian EST Assyrian I Aramaic ASR Ewe EWE Anyi-Baule AYB Ewondo EWO Aymara AYM Fang FAN Azeri AZE Fijian FIJ Bamileke (Any) BAI Finnish FIN Balochi BAL Fon FON Beja I Bedawi BEJ French FRN Belarusian BEL Fula I Fulfulde-Pulaar FUL Bemba BEM Ga GAA Bhojpuri BHO Gaelic / Irish GAE Bikol BIK Gaelic (Scotland) GAL Balti Tibetan BLT Georgian GEO Burmese I Myanma BMA German GER Bengali BNG Gago I Chigogo GGO Bengali (Any Other) BNGA Kikuyu I Gikuyu GKY Bengali (Chittagong I BNGC Galician I Galego GLG Noakhali) Greek GRE Bengali (Sylheti) BNGS Greek (Any Other) GREA British Sign Language BSL Greek (Cyprus) GREC Basque I Euskara BSQ Guarani GRN Bulgarian BUL Gujarati GUJ Cambodian I Khmer CAM Gurenne I Frafra GUN Catalan CAT Gurma GUR Caribbean Creole English CCE Hausa HAU Caribbean Creole French CCF Hindko HOK Chaga CGA Hebrew HEB Chattisgarhi I Khatahi CGR