Structure and Biochemistry of Cadherins and Catenins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supp. Table S2: Domains and Protein Families with a Putative Role in Host-Symbiont Interactions

Supp. Table S2: Domains and protein families with a putative role in host-symbiont interactions. The domains and protein families listed here were included in the comparisons in Figure 5 and Supp. Figure S5, which show the percentage of the respective protein groups in the Riftia symbiont metagenome and in metagenomes of other symbiotic and free-living organisms. % bacterial, total number bacterial: Percentage and total number of bacterial species in which this domain is found in the SMART database (January 2019). Domain name Pfam/SMART % bacterial (total Literature/comment annotation number bacterial) Alpha-2- alpha-2- A2M: 42.05% (2057) A2Ms: protease inhibitors which are important for eukaryotic macroglobulin macroglobulin innate immunity, if present in prokaryotes apparently fulfill a family (A2M), similar role, e.g. protection against host proteases (1) including N- terminal MG1 domain ANAPC Anaphase- APC2: 0 Ubiquitin ligase, important for cell cycle control in eukaryotes (2) promoting complex Bacterial proteins might interact with ubiquitination pathways in subunits the host (3) Ankyrin Ankyrin repeats 10.88% (8348) Mediate protein-protein interactions without sequence specificity (4) Sponge symbiont ankyrin-repeat proteins inhibit amoebal phagocytosis (5) Present in sponge microbiome metatranscriptomes, putative role in symbiont-host interactions (6) Present in obligate intracellular amoeba symbiont Candidatus Amoebophilus asiaticus genome, probable function in interactions with the host (7) Armadillo Armadillo repeats 0.83% (67) -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Armc5 Deletion Causes Developmental Defects and Compromises T-Cell Immune Responses

ARTICLE Received 26 Jan 2016 | Accepted 4 Nov 2016 | Published 7 Feb 2017 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms13834 OPEN Armc5 deletion causes developmental defects and compromises T-cell immune responses Yan Hu 1,*, Linjiang Lao1,*, Jianning Mao1, Wei Jin1, Hongyu Luo1, Tania Charpentier2, Shijie Qi1, Junzheng Peng1, Bing Hu3, Mieczyslaw Martin Marcinkiewicz4, Alain Lamarre2 & Jiangping Wu1,5 Armadillo repeat containing 5 (ARMC5) is a cytosolic protein with no enzymatic activities. Little is known about its function and mechanisms of action, except that gene mutations are associated with risks of primary macronodular adrenal gland hyperplasia. Here we map Armc5 expression by in situ hybridization, and generate Armc5 knockout mice, which are small in body size. Armc5 knockout mice have compromised T-cell proliferation and differentiation into Th1 and Th17 cells, increased T-cell apoptosis, reduced severity of experimental autoimmune encephalitis, and defective immune responses to lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. These mice also develop adrenal gland hyperplasia in old age. Yeast 2-hybrid assays identify 16 ARMC5-binding partners. Together these data indicate that ARMC5 is crucial in fetal development, T-cell function and adrenal gland growth homeostasis, and that the functions of ARMC5 probably depend on interaction with multiple signalling pathways. 1 Centre de recherche (CR), Centre hospitalier de l’Universite´ de Montre´al (CHUM), 900 Rue Saint Denis, Montre´al, Que´bec, Canada H2X 0A9. 2 Institut national de la recherche scientifique—Institut Armand-Frappier (INRS-IAF), 531 Boul. des Prairies, Laval, Que´bec, Canada H7V 1B7. 3 Anatomic Pathology, AmeriPath Central Florida, 4225 Fowler Ave. Tampa, Orlando, Florida 33617, USA. -

Comprehensive Computational Analysis of Leucine-Rich Repeat (LRR) Proteins Encoded in the Genome of the Diatom Phaeodactylum Tricornutum

Erschienen in: Marine Genomics ; 21 (2015). - S. 43-51 https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.margen.2015.02.007 Comprehensive computational analysis of leucine-rich repeat (LRR) proteins encoded in the genome of the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum Birgit Schulze ⁎, Matthias T. Buhmann 1, Carolina Río Bártulos, Peter G. Kroth Department of Biological Sciences, Universität Konstanz, 78457 Konstanz, Germany abstract We have screened the genome of the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum for gene models encoding proteins exhibiting leucine rich repeat (LRR) structures. In order to reveal the functionality of these proteins, their amino acid sequences were scanned for known domains and for homologies to other proteins. Additionally, proteins were categorized into different LRR families according to the variable sequence part of their LRR. This approach enabled us to group proteins with potentially similar functionality and to classify also LRR proteins Keywords: where no characterized homologues in other organisms exist. Most interestingly, we were able to indentify LRR several transmembrane LRR proteins, which are likely to function as receptor like molecules. However, none Receptor-like protein of them carry additional domains that are typical for mammalian or plant like receptors. Thus, the respective Adhesion protein signal recognition pathways seem to be substantially different in diatoms. Moreover, P. tricornutum encodes a RanGAP family of secreted LRR proteins likely to function as adhesion or binding proteins as part of the extracellular matrix. Additionally, intracellular LRR only proteins were divided into proteins similar to RasGTPase activators, regulators of nuclear transport, and mitotic regulation. Our approach allowed us to draw a detailed picture of the conservation and diversification of LRR proteins in the marine diatom P. -

Armadillo Repeat Proteins: Beyond the Animal Kingdom Coates, Juliet

University of Birmingham Armadillo repeat proteins: beyond the animal kingdom Coates, Juliet DOI: 10.1016/S0962-8924(03)00167-3 Document Version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (Harvard): Coates, J 2003, 'Armadillo repeat proteins: beyond the animal kingdom', Trends in Cell Biology, vol. 13, no. 9, pp. 463-471. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-8924(03)00167-3 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Rigid Fusions of Designed Helical Repeat Binding Proteins Efficiently

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Rigid fusions of designed helical repeat binding proteins efciently protect a binding surface from crystal contacts Patrick Ernst1, Annemarie Honegger1, Floor van der Valk1, Christina Ewald1,2, Peer R. E. Mittl1 & Andreas Plückthun1* Designed armadillo repeat proteins (dArmRPs) bind extended peptides in a modular way. The consensus version recognises alternating arginines and lysines, with one dipeptide per repeat. For generating new binding specifcities, the rapid and robust analysis by crystallography is key. Yet, we have previously found that crystal contacts can strongly infuence this analysis, by displacing the peptide and potentially distorting the overall geometry of the scafold. Therefore, we now used protein design to minimise these efects and expand the previously described concept of shared helices to rigidly connect dArmRPs and designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins), which serve as a crystallisation chaperone. To shield the peptide-binding surface from crystal contacts, we rigidly fused two DARPins to the N- and C-terminal repeat of the dArmRP and linked the two DARPins by a disulfde bond. In this ring-like structure, peptide binding, on the inside of the ring, is very regular and undistorted, highlighting the truly modular binding mode. Thus, protein design was utilised to construct a well crystallising scafold that prevents interference from crystal contacts with peptide binding and maintains the equilibrium structure of the dArmRP. Rigid DARPin-dArmRPs fusions will also be useful when chimeric binding proteins with predefned geometries are required. Designed Armadillo repeat proteins (dArmRPs) bind to elongated peptide sequences and may eventually com- plement classical detection antibodies (a review on alternative binding scafolds can be found in ref.1, their use in therapeutics is reviewed in ref.2). -

'Design of Armadillo Repeat Protein Scaffolds'

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2008 Design of armadillo repeat protein scaffolds Parmeggiani, F Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-4818 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Parmeggiani, F. Design of armadillo repeat protein scaffolds. 2008, University of Zurich, Faculty of Medicine. Design of Armadillo Repeat Protein Scaffolds Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Fabio Parmeggiani aus Italien Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Andreas Plückthun (Leitung der Dissertation) Prof. Dr. Markus Grütter Prof. Dr. Donald Hilvert Zürich, 2008 To my grandfather, who showed me the essence of curiosity “It is easy to add more of the same to old knowledge, but it is difficult to explain the new” Benno Müller-Hill Table of Contents 1 Table of contents Summary 3 Chapter 1: Peptide binders 7 Part I: Peptide binders 8 Modular interaction domains as natural peptide binders 9 SH2 domains 10 PTB domains 10 PDZ domains 12 14-3-3 domains 12 SH3 domains 12 WW domains 12 Peptide recognition by major histocompatibility complexes 13 Repeat proteins targeting peptides 15 Armadillo repeat proteins 16 Tetratricopeptide repeat proteins (TPR) 16 Beta propellers 16 Peptide binding by antibodies 18 Alternative scaffolds: a new approach to peptide binding 20 Part -

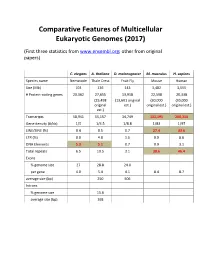

Comparative Features of Multicellular Eukaryotic Genomes (2017)

Comparative Features of Multicellular Eukaryotic Genomes (2017) (First three statistics from www.ensembl.org; other from original papers) C. elegans A. thaliana D. melanogaster M. musculus H. sapiens Species name Nematode Thale Cress Fruit Fly Mouse Human Size (Mb) 103 136 143 3,482 3,555 # Protein-coding genes 20,362 27,655 13,918 22,598 20,338 (25,498 (13,601 original (30,000 (30,000 original est.) original est.) original est.) est.) Transcripts 58,941 55,157 34,749 131,195 200,310 Gene density (#/kb) 1/5 1/4.5 1/8.8 1/83 1/97 LINE/SINE (%) 0.4 0.5 0.7 27.4 33.6 LTR (%) 0.0 4.8 1.5 9.9 8.6 DNA Elements 5.3 5.1 0.7 0.9 3.1 Total repeats 6.5 10.5 3.1 38.6 46.4 Exons % genome size 27 28.8 24.0 per gene 4.0 5.4 4.1 8.4 8.7 average size (bp) 250 506 Introns % genome size 15.6 average size (bp) 168 Arabidopsis Chromosome Structures Sorghum Whole Genome Details Characterizing the Proteome The Protein World • Sequencing has defined o Many, many proteins • How can we use this data to: o Define genes in new genomes o Look for evolutionarily related genes o Follow evolution of genes ▪ Mixing of domains to create new proteins o Uncover important subsets of genes that ▪ That deep phylogenies • Plants vs. animals • Placental vs. non-placental animals • Monocots vs. dicots plants • Common nomenclature needed o Ensure consistency of interpretations InterPro (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) Classification of Protein Families • Intergrated documentation resource for protein super families, families, domains and functional sites o Mitchell AL, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, et al. -

Appub0358.Pdf

Journal of Structural Biology 185 (2014) 147–162 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Structural Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yjsbi Designing protein function Modular peptide binding: From a comparison of natural binders to designed armadillo repeat proteins ⇑ Christian Reichen, Simon Hansen, Andreas Plückthun Department of Biochemistry, University of Zurich, 8057 Zurich, Switzerland article info abstract Article history: Several binding scaffolds that are not based on immunoglobulins have been designed as alternatives to Available online 3 August 2013 traditional monoclonal antibodies. Many of them have been developed to bind to folded proteins, yet cel- lular networks for signaling and protein trafficking often depend on binding to unfolded regions of pro- Keywords: teins. This type of binding can thus be well described as a peptide–protein interaction. In this review, we Protein engineering compare different peptide-binding scaffolds, highlighting that armadillo repeat proteins (ArmRP) offer an Libraries attractive modular system, as they bind a stretch of extended peptide in a repeat-wise manner. Instead of Proteomics generating each new binding molecule by an independent selection, preselected repeats – each comple- Protein design mentary to a piece of the target peptide – could be designed and assembled on demand into a new pro- Repeat proteins Peptide binding tein, which then binds the prescribed complete peptide. Stacked armadillo repeats (ArmR), each typically Protein–peptide interactions consisting of 42 amino acids arranged in three a-helices, build an elongated superhelical structure which enables binding of peptides in extended conformation. A consensus-based design approach, comple- mented with molecular dynamics simulations and rational engineering, resulted in well-expressed monomeric proteins with high stability. -

Use of Protein Engineering Techniques to Elucidate Protein Folding Pathways

Provided for non-commercial research and educational use only. Not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use. This chapter was originally published in the book Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, Vol. 84, published by Elsevier, and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author's benefit and for the benefit of the author's institution, for non-commercial research and educational use including without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specific colleagues who know you, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including without limitation commercial reprints, selling or licensing copies or access, or posting on open internet sites, your personal or institution’s website or repository, are prohibited. For exceptions, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier's permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial From: Anna L. Mallam and Sophie E. Jackson, Use of Protein Engineering Techniques to Elucidate Protein Folding Pathways. In P. Michael Conn, editor: Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, Vol. 84, Burlington: Academic Press, 2008, pp. 57-113. ISBN: 978-0-12-374595-8 © Copyright 2008 Elsevier Inc. Academic Press. Author's personal copy Use of Protein Engineering Techniques to Elucidate Protein Folding Pathways Anna L. Mallam and Sophie E. Jackson Department of Chemistry, Cambridge, CB2 1EW, United Kingdom I. Introduction............................................................................... 58 II. Early Protein Engineering Studies of Folding Pathways ........................ 59 III. Single Point Mutations and F‐Value Analysis...................................... 61 A. Mixed a/b Proteins .................................................................. 65 B. All‐a‐Helical Proteins............................................................... 69 C. All‐b‐Proteins........................................................................ -

Suppl Figure 1

Suppl Table 2. Gene Annotation (October 2011) for the selected genes used in the study. Locus Identifier Gene Model Description AT5G51780 basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) DNA-binding superfamily protein; FUNCTIONS IN: DNA binding, sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity; INVOLVED IN: regulation of transcription; LOCATED IN: nucleus; CONTAINS InterPro DOMAIN/s: Helix-loop-helix DNA-binding domain (InterPro:IPR001092), Helix-loop-helix DNA-binding (InterPro:IPR011598); BEST Arabidopsis thaliana protein match is: basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) D AT3G53400 BEST Arabidopsis thaliana protein match is: conserved peptide upstream open reading frame 47 (TAIR:AT5G03190.1); Has 285 Blast hits to 285 proteins in 23 species: Archae - 0; Bacteria - 0; Metazoa - 1; Fungi - 0; Plants - 279; Viruses - 0; Other Eukaryotes - 5 (source: NCBI BLink). AT1G44760 Adenine nucleotide alpha hydrolases-like superfamily protein; FUNCTIONS IN: molecular_function unknown; INVOLVED IN: response to stress; EXPRESSED IN: 22 plant structures; EXPRESSED DURING: 13 growth stages; CONTAINS InterPro DOMAIN/s: UspA (InterPro:IPR006016), Rossmann-like alpha/beta/alpha sandwich fold (InterPro:IPR014729); BEST Arabidopsis thaliana protein match is: Adenine nucleotide alpha hydrolases-li AT4G19950 unknown protein; BEST Arabidopsis thaliana protein match is: unknown protein (TAIR:AT5G44860.1); Has 338 Blast hits to 330 proteins in 72 species: Archae - 2; Bacteria - 94; Metazoa - 7; Fungi - 0; Plants - 232; Viruses - 0; Other Eukaryotes - 3 (source: NCBI BLink). AT3G14280 -

Armadillo-Repeat Protein Functions: Questions for Little Creatures Tewari, R; Bailes, E; Bunting, KA; Coates, Juliet

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Portal University of Birmingham Armadillo-repeat protein functions: questions for little creatures Tewari, R; Bailes, E; Bunting, KA; Coates, Juliet DOI: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.05.003 Document Version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (Harvard): Tewari, R, Bailes, E, Bunting, KA & Coates, J 2010, 'Armadillo-repeat protein functions: questions for little creatures', Trends in Cell Biology, vol. 20, no. 8, pp. 470-481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2010.05.003 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document.