Of the Chang Tang Wildlife Reserve in Tibet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf :Tgwf/L Jgohgt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7316/wild-mammals-of-the-annapurna-conservation-area-cggk-0f-if0f-if-qsf-tgwf-l-jgohgt-wild-mammals-of-the-annapurna-conservation-area-2019-127316.webp)

Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf :Tgwf/L Jgohgt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019

Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019 ISBN 978-9937-8522-8-9978-9937-8522-8-9 9 789937 852289 National Trust for Nature Conservation Annapurna Conservation Area Project Khumaltar, Lalitpur, Nepal Hariyo Kharka, Pokhara, Kaski, Nepal National Trust for Nature Conservation P.O. Box: 3712, Kathmandu, Nepal P.O. Box: 183, Kaski, Nepal Tel: +977-1-5526571, 5526573, Fax: +977-1-5526570 Tel: +977-61-431102, 430802, Fax: +977-61-431203 Annapurna Conservation Area Project Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.ntnc.org.np Website: www.ntnc.org.np 2019 Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' National Trust for Nature Conservation Annapurna Conservation Area Project 2019 Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' Published by © NTNC-ACAP, 2019 All rights reserved Any reproduction in full or in part must mention the title and credit NTNC-ACAP. Reviewers Prof. Karan Bahadur Shah (Himalayan Nature), Dr. Naresh Subedi (NTNC, Khumaltar), Dr. Will Duckworth (IUCN) and Yadav Ghimirey (Friends of Nature, Nepal). Compilers Rishi Baral, Ashok Subedi and Shailendra Kumar Yadav Suggested Citation Baral R., Subedi A. & Yadav S.K. (Compilers), 2019. Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area. National Trust for Nature Conservation, Annapurna Conservation Area Project, Pokhara, Nepal. First Edition : 700 Copies ISBN : 978-9937-8522-8-9 Front Cover : Yellow-bellied Weasel (Mustela kathiah), back cover: Orange- bellied Himalayan Squirrel (Dremomys lokriah). -

Division of Law Enforcement

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Division of Law Enforcement Annual Report FY 2000 The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, working with others, conserves, protects, and enhances fish and wildlife and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people. As part of this mission, the Service is responsible for enforcing U.S. and international laws, regulations, and treaties that protect wildlife resources. Cover photo by J & K Hollingsworth/USFWS I. Overview ..................................................................................................................1 Program Evolution and Priorities......................................................................2 Major Program Components ..............................................................................2 FY 2000 Investigations Statistical Summary (chart) ....................................3 FY 1999-2000 Wildlife Inspection Activity (chart) ..........................................6 Table of Laws Enforced ......................................................................................................7 Contents II. Organizational Structure ........................................................................................9 III. Regional Highlights ..............................................................................................14 Region One ..........................................................................................................14 Region Two ..........................................................................................................26 -

Project Report 2010-2011

FOOD HABITS AND OVERLAPS BETWEEN LIVESTOCK AND MONGOLIAN SAIGA PROJECT REPORT 2010-2011 Bayarbaatar Buuveibaatar Gundensambuu Gunbat Correspondence: Buuveibaatar Bayarbaatar. PhD Student, Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst 01003, USA [email protected] & Wildlife Conservation Society, Mongolia Program, “Internom” Bookstore 3rd Floor, Ulaanbaatar 211238, Mongolia Abstract The Mongolian saiga (Saiga tatarica mongolica) is listed as a critically endangered antelope in IUCN Red list and their conservation is urgently needed. Recent increases in livestock numbers have potentially reduced the capacity of habitats to sustain saiga because of forage or interference competition. We studied the potential for forage competition between saiga and domestic livestock in Shargyn Gobi, western Mongolia by quantifying diet overlaps using microscopic analysis of fecal samples. We collected 10 fecal samples from each of saiga, goat, sheep, horse, and camels in summer of 2011. We also established 105 plots at sightings of marked saiga antelope in June 2011 to determine vegetation community within saiga range. Each plot was subdivided into 5 adjacent 1 m2 square quadrats and the plants in them were surveyed. Onions or Allium appeared greater proportions in the diet composition of saiga, goat, and sheep. Diet composition of camels consisted mainly from shrubs, whereas Stipa was the dominantly found in the diet of horses. Among twenty-five plant species were recorded in the vegetation plots, Allium sp was the most frequently occurred species. The food habits of Mongolian saiga were quite similar to those of sheep and goats but were different from those of horses and camels. Our results suggest the saiga and sheep/goats would potentially be competitive on pasture as were suggested in similar study on Mongolian gazelle and argali sheep in Mongolia. -

Towards Snow Leopard Prey Recovery: Understanding the Resource Use Strategies and Demographic Responses of Bharal Pseudois Nayaur to Livestock Grazing and Removal

Towards snow leopard prey recovery: understanding the resource use strategies and demographic responses of bharal Pseudois nayaur to livestock grazing and removal Final project report submitted by Kulbhushansingh Suryawanshi Nature Conservation Foundation, Mysore Post-graduate Program in Wildlife Biology and Conservation, National Centre for Biological Sciences, Wildlife Conservation Society –India program, Bangalore, India To Snow Leopard Conservation Grant Program January 2009 Towards snow leopard prey recovery: understanding the resource use strategies and demographic responses of bharal Pseudois nayaur to livestock grazing and removal. 1. Executive Summary: Decline of wild prey populations in the Himalayan region, largely due to competition with livestock, has been identified as one of the main threats to the snow leopard Uncia uncia. Studies show that bharal Pseudois nayaur diet is dominated by graminoids during summer, but the proportion of graminoids declines in winter. We explore the causes for the decline of graminoids from bharal winter diet and resulting implications for bharal conservation. We test the predictions generated by two alternative hypotheses, (H1) low graminoid availability caused by livestock grazing during winter causes bharal to include browse in their diet, and, (H2) bharal include browse, with relatively higher nutrition, to compensate for the poor quality of graminoids during winter. Graminoid availability was highest in areas without livestock grazing, followed by areas with moderate and intense livestock grazing. Graminoid quality in winter was relatively lower than that of browse, but the difference was not statistically significant. Bharal diet was dominated by graminoids in areas with highest graminoid availability. Graminoid contribution to bharal diet declined monotonically with a decline in graminoid availability. -

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-Hðgå-ÅÛ-Hýh-ºiô-;Ým-Mû-Ç+Ô¼-¾-Zçàz-Çeômü

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-hÝh-ºIô-;Ým-mÛ-Ç+ô¼-¾-zÇÀz-Çeômü Tahir Shawl Jigmet Takpa Phuntsog Tashi Yamini Panchaksharam 2 FOREWORD Ladakh is one of the most wonderful places on earth with unique biodiversity. I have the privilege of forwarding the fi eld guide on mammals of Ladakh which is part of a series of bilingual (English and Ladakhi) fi eld guides developed by WWF-India. It is not just because of my involvement in the conservation issues of the state of Jammu & Kashmir, but I am impressed with the Ladakhi version of the Field Guide. As the Field Guide has been specially produced for the local youth, I hope that the Guide will help in conserving the unique mammal species of Ladakh. I also hope that the Guide will become a companion for every nature lover visiting Ladakh. I commend the efforts of the authors in bringing out this unique publication. A K Srivastava, IFS Chief Wildlife Warden, Govt. of Jammu & Kashmir 3 ÇSôm-zXôhü ¾-hÐGÅ-mÛ-ºWÛG-dïm-mP-¾-ÆôG-VGÅ-Ço-±ôGÅ-»ôh-źÛ-GmÅ-Å-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-ŸÛG-»Ûm-môGü ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Å-GmÅ-;Ým-¾-»ôh-qºÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚Å-q-ºhÛ-¾-ÇSôm-zXôh-‚ô-‚Å- qôºÛ-PºÛ-¾Å-ºGm-»Ûm-môGü ºÛ-zô-P-¼P-W¤-¤Þ-;-ÁÛ-¤Û¼-¼Û-¼P-zŸÛm-D¤-ÆâP-Bôz-hP- ºƒï¾-»ôh-¤Dm-qôÅ-‚Å-¼ï-¤m-q-ºÛ-zô-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Ç+h-hï-mP-P-»ôh-‚Å-qôº-È-¾Å-bï-»P- zÁh- »ôPÅü Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚ô-‚Å-qô-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-¾ÛÅ-GŸôm-mÝ-;Ým-¾-wm-‚Å-¾-ºwÛP-yï-»Ûm- môG ºô-zôºÛ-;-mÅ-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-Tm-mÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-BôzÅ-¾-wm-qºÛ-¼Û-zô-»Ûm- hôm-m-®ôGÅ-¾ü ¼P-zŸÛm-D¤Å-¾-ºfh-qô-»ôh-¤Dm-±P-¤-¾ºP-wm-fôGÅ-qºÛ-¼ï-z-»Ûmü ºhÛ-®ßGÅ-ºô-zM¾-¤²h-hï-ºƒÛ-¤Dm-mÛ-ºhÛ-hqï-V-zô-q¼-¾-zMz-Çeï-Çtï¾-hGôÅ-»Ûm-môG Íï-;ï-ÁÙÛ-¶Å-b-z-ͺÛ-Íïw-ÍôÅ- mGÅ-±ôGÅ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-Bôz-Çkï-DG-GÛ-hqôm-qô-G®ô-zô-W¤- ¤Þ-;ÁÛ-¤Û¼-GŸÝP.ü 4 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The fi eld guide is the result of exhaustive work by a large number of people. -

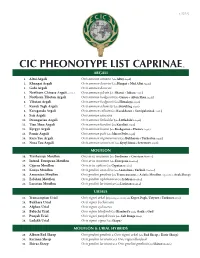

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Surveys at a Tibetan Antelope Pantholops Hodgsonii Calving Ground Adjacent to the Arjinshan Nature Reserve, Xinjiang, China: Decline and Recovery of a Population

Surveys at a Tibetan antelope Pantholops hodgsonii calving ground adjacent to the Arjinshan Nature Reserve, Xinjiang, China: decline and recovery of a population W illiamV.Bleisch,PaulJ.Buzzard,HuibinZ hang,DonghuaX U¨ ,ZhihuL iu W eidong L i and H owman W ong Abstract Females in most populations of chiru or Tibetan Leslie & Schaller, 2008). Despite the remoteness of chiru antelope Pantholops hodgsonii migrate each year up to 350 km habitat, however, there was an upsurge in poaching during to summer calving grounds, and these migrations charac- the 1980s and 1990s for its extraordinarily fine wool known terize the Tibet/Qinghai Plateau. We studied the migratory as shahtoosh (Wright & Kumar, 1998). Poaching raised the chiru population at the Ullughusu calving grounds south- threat of extirpation for many chiru populations (Harris west of the Arjinshan Nature Reserve in Xinjiang, China. et al., 1999; Bleisch et al., 2004; Fauna & Flora International, 2 The 750–1,000 km of suitable habitat at Ullughusu is at 2004). Competition with livestock for grazing has been and 4,500–5,000 m with sparse vegetation. We used direct meth- continues to be a threat and, more recently, infrastructure ods (block counts, vehicle and walking transects and radial development, fencing of pasture and gold mining have point sampling) and an indirect method (pellet counts) become increasing problems (Bleisch et al., 2004; Fauna & during six summers to assess population density. We also Flora International, 2004; Xia et al., 2007; Fox et al., 2009). witnessed and stopped two major poaching events, in 1998 Chiru are categorized on the IUCN Red List as Endangered and 1999 (103 and 909 carcasses, respectively). -

IUCN Briefing Paper

BRIEFING PAPER September 2016 Contact information updated April 2019 Informing decisions on trophy hunting A Briefing Paper regarding issues to be taken into account when considering restriction of imports of hunting trophies For more information: SUMMARY Dilys Roe Trophy hunting is currently the subject of intense debate, with moves IUCN CEESP/SSC Sustainable Use at various levels to end or restrict it, including through increased bans and Livelihoods or restrictions on carriage or import of trophies. This paper seeks to inform SpecialistGroup these discussions. [email protected] Patricia Cremona IUCN Global Species (such as large antlers), and overlaps with widely practiced hunting for meat. Programme It is clear that there have been, and continue to be, cases of poorly conducted [email protected] and poorly regulated hunting. While “Cecil the Lion” is perhaps the most highly publicised controversial case, there are examples of weak governance, corruption, lack of transparency, excessive quotas, illegal hunting, poor monitoring and other problems in a number of countries. This poor practice requires urgent action and reform. However, legal, well regulated trophy Habitat loss and degradation is a primary hunting programmes can, and do, play driver of declines in populations an important role in delivering benefits of terrestrial species. Demographic change for both wildlife conservation and for and corresponding demands for land for the livelihoods and wellbeing of indigenous development are increasing in biodiversity- and local communities living with wildlife. rich parts of the globe, exacerbating this pressure on wildlife and making the need for viable conservation incentives more urgent. © James Warwick RECOMMENDATIONS and the rights and livelihoods of indigenous and local communities, IUCN calls on relevant decision- makers at all levels to ensure that any decisions that could restrict or end trophy hunting programmes: i. -

Is Trophy Hunting of Bharal (Blue Sheep) and Himalayan Tahr Contributing to Their Conservation in Nepal?

Published by Associazione Teriologica Italiana Volume 26 (2): 85–88, 2015 Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy Available online at: http://www.italian-journal-of-mammalogy.it/article/view/11210/pdf doi:10.4404/hystrix-26.2-11210 Research Article Is trophy hunting of bharal (blue sheep) and Himalayan tahr contributing to their conservation in Nepal? Achyut Aryala,∗, Maheshwar Dhakalb, Saroj Panthic, Bhupendra Prasad Yadavb, Uttam Babu Shresthad, Roberta Bencinie, David Raubenheimerf, Weihong Jia aInstitute of Natural and Mathematical Sciences, Massey University, Auckland, New Zealand bDepartment of National Park and Wildlife Conservation, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Government of Nepal, Nepal cDistrict Forest Office, Darchula, Department of Forest, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Government of Nepal, Nepal dInstitute for Agriculture and the Environment, University of Southern Queensland, Australia eSchool of Animal Biology, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, Western Australia, Australia fThe Charles Perkins Centre and Faculty of Veterinary Science and School of Biological Sciences, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia Keywords: Abstract Bharal Himalayan tahr Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve (DHR), the only hunting reserve in Nepal, is famous for trophy hunt- hunting ing of bharal or “blue sheep” (Pseudois nayaur) and Himalayan tahr (Hemitragus jemlahicus). conservation Although trophy hunting has been occurring in DHR since 1987, its ecological consequences are local community poorly known. We assessed the ecological consequences of bharal and Himalayan tahr hunting in revenue DHR, and estimated the economic contribution of hunting to the government and local communit- sex ratio population ies based on the revenue data. The bharal population increased significantly from 1990 to 2011, but the sex ratio became skewed from male-biased (129 Male:100 Female) in 1990 to female-biased (82 Male:100 Female) in 2011. -

Influence of Trophy Harvest on the Population Age Structure of Argali Ovis Ammon in Mongolia

Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 109(3), Sept-Dec 2012 173-176 INFLUENCE OF TROPHY HARVEST ON ARGALI POPULATION INFLUENCE OF TROPHY HARVEST ON THE POPULATION AGE STRUCTURE OF ARGALI OVIS AMMON IN MONGOLIA MICHAEL R. FRISINA1 AND R. MARGARET FRISINA2 1Montana State University Bozeman, Department of Animal and Range Sciences, Bozeman, MT. 59717 USA. Email: [email protected] 2August L. Hormay Wildlands Institute, PO Box 4712, Butte, MT. 59701 USA. To assess the influence of trophy hunting on Mongolian Argali Ovis ammon, we compared the ages of trophy rams (n=64) taken through Mongolia’s legal hunting programme with those of mature rams that died of natural causes (n=116). A two-sample Kolomogorov-Smirnov test indicated that the distributions of the two groups were different (P=0.001). A two-sample t-test indicated the distributional differences were due, at least in part, to differences in the mean ages between the natural deaths and hunter harvested samples (P=0.001); the distributions were not centered at the same value or the means in the two populations differ. Application of the Central Limit Theorem affirms that the distribution of the sample mean ages for natural death and hunter harvested populations will be approximately normal, making the t-test applicable. The mean age for the natural death sample was 8.7 years (range: 7.0–13.0) compared to 9.4 (range: 7.0–13) for the hunter harvested sample. At the 95% confidence level, the true difference in ages between the trophy kills and natural deaths is between 3 months and 1 year. -

Argali (Ovis Ammon) Conservation in Western Mongolia and the Altai-Sayan

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2003 Argali (Ovis ammon) conservation in western Mongolia and the Altai-Sayan Ryan L. Maroney The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Maroney, Ryan L., "Argali (Ovis ammon) conservation in western Mongolia and the Altai-Sayan" (2003). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 6497. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/6497 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes” or "No” and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author’s Signature; Date: Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 ARGALI ipvis ammon) CONSERVATION IN WESTERN MONGOLIA AND THE ALTAI SAYAN by Ryan L. Maroney B.A., New College, Sarasota, Florida, 1999 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science The University of Montana 2003 Approved by Chairperson Dean, Graduate School Date UMI Number: EP37298 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Identification Guidelines for Shahtoosh & Pashmina

Shahtoosh (aka Shah tush) is the trade name for woolen garments, usually shawls, made from the hair of the Tibetan antelope (Pantholops hodgsonii). Also called a chiru, it is considered an endangered species, and the importation of any part or product of Pantholops is prohib- ited by U.S. law. Chiru originate in the high Himalaya Mountains of Tibet, western China, and far northern India where they are killed for their parts. Their pelts are converted into shahtoosh, and horns of the males are taken as trophies. No chirus are kept in captivity, and it reportedly takes three to five individuals to make a single shawl (Wright & Kumar 1997). Trophy Head with Horns of male Pantholops hodgsonii SHAWL COLORS Off-white and brownish beige are the natural colors of the chiru’s pelage. Shahtoosh shawls in these natural colors are the most traditional. How- ever, shahtoosh can be dyed almost any color of the spectrum. Unless the fibers are dyed opaque black, most dyed fibers allow the transmission of light so that the internal characteristics are visible under a compound microscope. (See "Microscopic Characteristics" in Hints for Visual Identification.) DIFFERENT PATTERNS AND/OR DECORATION SIZES - Solid color - Standard shawl 36" x 81" - Plaid - Muffler 12" x 60" - Stripes - Man-size, Blanket 108" x 54" - Edged in wispy fringe - Couturier length (4' x 18' +) - Double color (each side of shawl is a different color) - All-over embroidery APPROXIMATE PRICE RANGES Cost Wholesale Retail Plain $550-$1,000 $700-$2,500 $1,500-$2,450 Pastels $700-$850 $1,300-$2,600 $1,800-$3,000 Checks/Plaids $600-$1,500 $800-$1,180 $1,300-$2,450 Stripe $600-$800 $1,300-$1,800 $2,450-$3,200 Double color $800-$1,000 $1,380-$2,800 $2,100-$3,200 Border embroidery $850-$3,050 $1,080-$1,600 $1,500-$3,200 All-over embroidery $800-$5,000 $1,380-$5,500 $3,000-$6,500 White $1,800 $2,300 $4,600 Above prices are for standard size shawls in year 2000.