Towards Snow Leopard Prey Recovery: Understanding the Resource Use Strategies and Demographic Responses of Bharal Pseudois Nayaur to Livestock Grazing and Removal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Division of Law Enforcement

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Division of Law Enforcement Annual Report FY 2000 The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, working with others, conserves, protects, and enhances fish and wildlife and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people. As part of this mission, the Service is responsible for enforcing U.S. and international laws, regulations, and treaties that protect wildlife resources. Cover photo by J & K Hollingsworth/USFWS I. Overview ..................................................................................................................1 Program Evolution and Priorities......................................................................2 Major Program Components ..............................................................................2 FY 2000 Investigations Statistical Summary (chart) ....................................3 FY 1999-2000 Wildlife Inspection Activity (chart) ..........................................6 Table of Laws Enforced ......................................................................................................7 Contents II. Organizational Structure ........................................................................................9 III. Regional Highlights ..............................................................................................14 Region One ..........................................................................................................14 Region Two ..........................................................................................................26 -

Project Report 2010-2011

FOOD HABITS AND OVERLAPS BETWEEN LIVESTOCK AND MONGOLIAN SAIGA PROJECT REPORT 2010-2011 Bayarbaatar Buuveibaatar Gundensambuu Gunbat Correspondence: Buuveibaatar Bayarbaatar. PhD Student, Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst 01003, USA [email protected] & Wildlife Conservation Society, Mongolia Program, “Internom” Bookstore 3rd Floor, Ulaanbaatar 211238, Mongolia Abstract The Mongolian saiga (Saiga tatarica mongolica) is listed as a critically endangered antelope in IUCN Red list and their conservation is urgently needed. Recent increases in livestock numbers have potentially reduced the capacity of habitats to sustain saiga because of forage or interference competition. We studied the potential for forage competition between saiga and domestic livestock in Shargyn Gobi, western Mongolia by quantifying diet overlaps using microscopic analysis of fecal samples. We collected 10 fecal samples from each of saiga, goat, sheep, horse, and camels in summer of 2011. We also established 105 plots at sightings of marked saiga antelope in June 2011 to determine vegetation community within saiga range. Each plot was subdivided into 5 adjacent 1 m2 square quadrats and the plants in them were surveyed. Onions or Allium appeared greater proportions in the diet composition of saiga, goat, and sheep. Diet composition of camels consisted mainly from shrubs, whereas Stipa was the dominantly found in the diet of horses. Among twenty-five plant species were recorded in the vegetation plots, Allium sp was the most frequently occurred species. The food habits of Mongolian saiga were quite similar to those of sheep and goats but were different from those of horses and camels. Our results suggest the saiga and sheep/goats would potentially be competitive on pasture as were suggested in similar study on Mongolian gazelle and argali sheep in Mongolia. -

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-Hðgå-ÅÛ-Hýh-ºiô-;Ým-Mû-Ç+Ô¼-¾-Zçàz-Çeômü

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-hÝh-ºIô-;Ým-mÛ-Ç+ô¼-¾-zÇÀz-Çeômü Tahir Shawl Jigmet Takpa Phuntsog Tashi Yamini Panchaksharam 2 FOREWORD Ladakh is one of the most wonderful places on earth with unique biodiversity. I have the privilege of forwarding the fi eld guide on mammals of Ladakh which is part of a series of bilingual (English and Ladakhi) fi eld guides developed by WWF-India. It is not just because of my involvement in the conservation issues of the state of Jammu & Kashmir, but I am impressed with the Ladakhi version of the Field Guide. As the Field Guide has been specially produced for the local youth, I hope that the Guide will help in conserving the unique mammal species of Ladakh. I also hope that the Guide will become a companion for every nature lover visiting Ladakh. I commend the efforts of the authors in bringing out this unique publication. A K Srivastava, IFS Chief Wildlife Warden, Govt. of Jammu & Kashmir 3 ÇSôm-zXôhü ¾-hÐGÅ-mÛ-ºWÛG-dïm-mP-¾-ÆôG-VGÅ-Ço-±ôGÅ-»ôh-źÛ-GmÅ-Å-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-ŸÛG-»Ûm-môGü ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Å-GmÅ-;Ým-¾-»ôh-qºÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚Å-q-ºhÛ-¾-ÇSôm-zXôh-‚ô-‚Å- qôºÛ-PºÛ-¾Å-ºGm-»Ûm-môGü ºÛ-zô-P-¼P-W¤-¤Þ-;-ÁÛ-¤Û¼-¼Û-¼P-zŸÛm-D¤-ÆâP-Bôz-hP- ºƒï¾-»ôh-¤Dm-qôÅ-‚Å-¼ï-¤m-q-ºÛ-zô-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Ç+h-hï-mP-P-»ôh-‚Å-qôº-È-¾Å-bï-»P- zÁh- »ôPÅü Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚ô-‚Å-qô-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-¾ÛÅ-GŸôm-mÝ-;Ým-¾-wm-‚Å-¾-ºwÛP-yï-»Ûm- môG ºô-zôºÛ-;-mÅ-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-Tm-mÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-BôzÅ-¾-wm-qºÛ-¼Û-zô-»Ûm- hôm-m-®ôGÅ-¾ü ¼P-zŸÛm-D¤Å-¾-ºfh-qô-»ôh-¤Dm-±P-¤-¾ºP-wm-fôGÅ-qºÛ-¼ï-z-»Ûmü ºhÛ-®ßGÅ-ºô-zM¾-¤²h-hï-ºƒÛ-¤Dm-mÛ-ºhÛ-hqï-V-zô-q¼-¾-zMz-Çeï-Çtï¾-hGôÅ-»Ûm-môG Íï-;ï-ÁÙÛ-¶Å-b-z-ͺÛ-Íïw-ÍôÅ- mGÅ-±ôGÅ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-Bôz-Çkï-DG-GÛ-hqôm-qô-G®ô-zô-W¤- ¤Þ-;ÁÛ-¤Û¼-GŸÝP.ü 4 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The fi eld guide is the result of exhaustive work by a large number of people. -

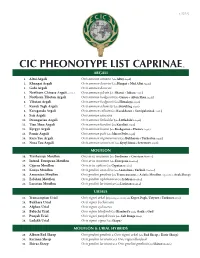

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Royle Safaris Sichuan Mammals Tour Trip Report

In March 2019 Royle Safaris ran our second specialist Sichuan Mammals Tour with a focus on a particularly special species. The trip was run with Martin Royle, Roland Zeidler & Sid Francis as our guides. We visited 3 different locations (covering the rugged bamboo forests of the greater Wolong ecosystem, the high altitude grasslands of Rouergai and the wonderful forests of Tangjiahe. We were very successful with sightings of 44 different species of mammals and over 100 species of birds including Giant Panda, Red Panda, Pallas’s Cat, Chinese Mountain Cat, Indochinese Leopard Cat, Particoloured Flying Squirrel, Golden Snub-nosed Monkey, Chinese Ferret Badger, Eurasian Otter and Chinese Pipistrelle. We ran a second Sichuan’s Mammals Tour (back to back with this one) in April 2019 and we had even more success in some areas. The sightings log for that trip will follow in a few days. We have started to promote our 2020 Sichuan Mammals Tour (with special focus on a particular special species for half of the trip); we have already received many bookings on these two trips. Our first tour for 2020 (9th – 22nd March 2020) has just one place remaining and our second tour for 2020 (25th April – 8th May 2020) which also has only one place remaining. We have also started offering places on another specialist mammal tour of China, visiting Qinghai and the wonderful Valley of the Cats. This tour is for July 2020 (1st – 15th July 2020) and focuses on Snow leopards, Eurasian lynx, Himalayan wolf, Himalayan brown bear, Tibetan antelope, Wild Yak, White-lipped deer, Alpine musk deer, Glover’s pika, Bharal, McNeil’s deer and many more species. -

Of the Chang Tang Wildlife Reserve in Tibet

RANGELANDS 18(3), June 1996 91 Rangelands of the Chang Tang Wildlife Reserve in Tibet Daniel J. Millerand George B. Schaller eastern part of the cious steppes and mountains that Chang Tang Reserve sweep along northern Tibet for almost based on our research in 800 miles east to west. The chang the fall of 1993 and sum- tang, a vast and vigorous landscape mer of 1994. We also comparable in size to the Great Plains discuss conservation of North America, is one of the highest, issues facing the reserve most remote and least known range- and the implications lands of the world. The land is too cold these have for develop- and arid to support forests and agricul- ment, management and ture; vegetation is dominated by cold- conservation. desert grasslands,with a sparse cover of grasses, sedges, forbs and low shrubs. It is one of the world's last Descriptionand great wildernessareas. Location The Chang Tang Wildlife Reserve was established by the Tibetan Located in the north- Autonomous governmentin of the Region western part 1993 to protect Tibet's last, major Tibetan Autonomous wildlife populationsand the grasslands Region (see Map 1), the depend upon. In the wildernessof Reserve they Chang Tang the Chang Tang Reservelarge herdsof encompasses approxi- Tibetan antelope still follow ancient mately 110,000 square trails on their annual migrationroutes to A nomad bundled the wind while Tibetan lady up against miles, (an area about birthing grounds in the far north. Wild herding. of the size Arizona), yaks, exterminated in most of Tibet, and is the second in maintain their last stronghold in the he Chang Tang Wildlife Reserve, area in the world. -

High Altitude Survival

High altitude survival Conflicts between pastoralism andwildlif e in the Trans-Himalaya Charudutt Mishra CENTRALE LANDBOUWCATALOGUS 0000 0873 6775 Promotor Prof.Dr .H .H .T .Prin s Hoogleraar inhe tNatuurbehee r ind eTrope n enEcologi eva n Vertebraten Co-promotor : Dr.S .E .Va nWiere n Universitair Docent, Leerstoelgroep Natuurbeheer in de Tropen enEcologi eva nVertebrate n Promotie Prof.Dr .Ir .A .J .Va n DerZijp p commissie Wageningen Universiteit Prof.Dr .J .H . Koeman Wageningen Universiteit Prof.Dr . J.P .Bakke r Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Prof.Dr .A .K .Skidmor e International Institute forAerospac e Survey and Earth Sciences, Enschede High altitude survival: conflicts between pastoralism and wildlife inth e Trans-Himalaya Charudutt Mishra Proefschrift ter verkrijging van degraa d van doctor opgeza g van derecto r magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit prof. dr. ir. L. Speelman, inhe t openbaar te verdedigen opvrijda g 14decembe r200 1 des namiddags te 13:30uu r in deAul a -\ •> Mishra, C. High altitude survival:conflict s between pastoralism andwildlif e inth e Trans-Himalaya Wageningen University, The Netherlands. Doctoral Thesis (2001); ISBN 90-5808-542-2 A^ofZC , "SMO Propositions 1. Classical nature conservation measures will not suffice, because the new and additional measures that have to be taken must be especially designed for those areas where people live and use resources (Herbert Prins, The Malawi principles: clarification of thoughts that underlaythe ecosystem approach). 2. The ability tomak e informed decisions on conservation policy remains handicapped due to poor understanding of the way people use natural resources, and the impacts of such resource use onwildlif e (This thesis). -

IUCN Briefing Paper

BRIEFING PAPER September 2016 Contact information updated April 2019 Informing decisions on trophy hunting A Briefing Paper regarding issues to be taken into account when considering restriction of imports of hunting trophies For more information: SUMMARY Dilys Roe Trophy hunting is currently the subject of intense debate, with moves IUCN CEESP/SSC Sustainable Use at various levels to end or restrict it, including through increased bans and Livelihoods or restrictions on carriage or import of trophies. This paper seeks to inform SpecialistGroup these discussions. [email protected] Patricia Cremona IUCN Global Species (such as large antlers), and overlaps with widely practiced hunting for meat. Programme It is clear that there have been, and continue to be, cases of poorly conducted [email protected] and poorly regulated hunting. While “Cecil the Lion” is perhaps the most highly publicised controversial case, there are examples of weak governance, corruption, lack of transparency, excessive quotas, illegal hunting, poor monitoring and other problems in a number of countries. This poor practice requires urgent action and reform. However, legal, well regulated trophy Habitat loss and degradation is a primary hunting programmes can, and do, play driver of declines in populations an important role in delivering benefits of terrestrial species. Demographic change for both wildlife conservation and for and corresponding demands for land for the livelihoods and wellbeing of indigenous development are increasing in biodiversity- and local communities living with wildlife. rich parts of the globe, exacerbating this pressure on wildlife and making the need for viable conservation incentives more urgent. © James Warwick RECOMMENDATIONS and the rights and livelihoods of indigenous and local communities, IUCN calls on relevant decision- makers at all levels to ensure that any decisions that could restrict or end trophy hunting programmes: i. -

Is Trophy Hunting of Bharal (Blue Sheep) and Himalayan Tahr Contributing to Their Conservation in Nepal?

Published by Associazione Teriologica Italiana Volume 26 (2): 85–88, 2015 Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy Available online at: http://www.italian-journal-of-mammalogy.it/article/view/11210/pdf doi:10.4404/hystrix-26.2-11210 Research Article Is trophy hunting of bharal (blue sheep) and Himalayan tahr contributing to their conservation in Nepal? Achyut Aryala,∗, Maheshwar Dhakalb, Saroj Panthic, Bhupendra Prasad Yadavb, Uttam Babu Shresthad, Roberta Bencinie, David Raubenheimerf, Weihong Jia aInstitute of Natural and Mathematical Sciences, Massey University, Auckland, New Zealand bDepartment of National Park and Wildlife Conservation, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Government of Nepal, Nepal cDistrict Forest Office, Darchula, Department of Forest, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Government of Nepal, Nepal dInstitute for Agriculture and the Environment, University of Southern Queensland, Australia eSchool of Animal Biology, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, Western Australia, Australia fThe Charles Perkins Centre and Faculty of Veterinary Science and School of Biological Sciences, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia Keywords: Abstract Bharal Himalayan tahr Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve (DHR), the only hunting reserve in Nepal, is famous for trophy hunt- hunting ing of bharal or “blue sheep” (Pseudois nayaur) and Himalayan tahr (Hemitragus jemlahicus). conservation Although trophy hunting has been occurring in DHR since 1987, its ecological consequences are local community poorly known. We assessed the ecological consequences of bharal and Himalayan tahr hunting in revenue DHR, and estimated the economic contribution of hunting to the government and local communit- sex ratio population ies based on the revenue data. The bharal population increased significantly from 1990 to 2011, but the sex ratio became skewed from male-biased (129 Male:100 Female) in 1990 to female-biased (82 Male:100 Female) in 2011. -

Influence of Trophy Harvest on the Population Age Structure of Argali Ovis Ammon in Mongolia

Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 109(3), Sept-Dec 2012 173-176 INFLUENCE OF TROPHY HARVEST ON ARGALI POPULATION INFLUENCE OF TROPHY HARVEST ON THE POPULATION AGE STRUCTURE OF ARGALI OVIS AMMON IN MONGOLIA MICHAEL R. FRISINA1 AND R. MARGARET FRISINA2 1Montana State University Bozeman, Department of Animal and Range Sciences, Bozeman, MT. 59717 USA. Email: [email protected] 2August L. Hormay Wildlands Institute, PO Box 4712, Butte, MT. 59701 USA. To assess the influence of trophy hunting on Mongolian Argali Ovis ammon, we compared the ages of trophy rams (n=64) taken through Mongolia’s legal hunting programme with those of mature rams that died of natural causes (n=116). A two-sample Kolomogorov-Smirnov test indicated that the distributions of the two groups were different (P=0.001). A two-sample t-test indicated the distributional differences were due, at least in part, to differences in the mean ages between the natural deaths and hunter harvested samples (P=0.001); the distributions were not centered at the same value or the means in the two populations differ. Application of the Central Limit Theorem affirms that the distribution of the sample mean ages for natural death and hunter harvested populations will be approximately normal, making the t-test applicable. The mean age for the natural death sample was 8.7 years (range: 7.0–13.0) compared to 9.4 (range: 7.0–13) for the hunter harvested sample. At the 95% confidence level, the true difference in ages between the trophy kills and natural deaths is between 3 months and 1 year. -

Human-Wildlife Conflict in the Chang Tang Region of Tibet

Human-Wildlife Conflict in the Chang Tang Region of Tibet: The Impact of Tibetan Brown Bears and Other Wildlife on Nomadic Herders Dawa Tsering, John Farrington, and Kelsang Norbu August 2006 WWF China – Tibet Program Author Contact Information: Dawa Tsering, Tibet Academy of Social Sciences and WWF China – Tibet Program Tashi Nota Hotel 24 North Linkuo Rd. Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region 850 000 People’s Republic of China [email protected] (+86)(891) 636-4380 John D. Farrington Tibet University 36 Jiangsu Road Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region 850 000 People’s Republic of China [email protected] [email protected] Kelsang Norbu WWF China – Tibet Program Tashi Nota Hotel 24 North Linkuo Rd. Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region 850 000 People’s Republic of China [email protected] Human-Wildlife Conflict in the Chang Tang Region of Tibet Abstract The multiple-use Chang Tang and Seling Lake Nature Reserves were created in 1993 to protect the unique assemblage of large fauna inhabiting the high-altitude steppe grasslands of northern Tibet, including the Tibetan antelope, Tibetan wild ass, Tibetan brown bear, Tibetan Gazelle, wild yak, and snow leopard. Prior to creation of the reserve, many of these species were heavily hunted for meat and sale of parts. Since creation of the reserve, however, killing of wildlife by subsistence hunters and commercial poachers has declined while in the past five years a new problem has emerged, that of human-wildlife conflict. With human, livestock, and wildlife populations in the reserves all increasing, and animals apparently emboldened by reserve-wide hunting bans, all forms of human-wildlife conflict have surged rapidly since 2001. -

Argali (Ovis Ammon) Conservation in Western Mongolia and the Altai-Sayan

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2003 Argali (Ovis ammon) conservation in western Mongolia and the Altai-Sayan Ryan L. Maroney The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Maroney, Ryan L., "Argali (Ovis ammon) conservation in western Mongolia and the Altai-Sayan" (2003). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 6497. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/6497 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes” or "No” and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author’s Signature; Date: Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 ARGALI ipvis ammon) CONSERVATION IN WESTERN MONGOLIA AND THE ALTAI SAYAN by Ryan L. Maroney B.A., New College, Sarasota, Florida, 1999 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science The University of Montana 2003 Approved by Chairperson Dean, Graduate School Date UMI Number: EP37298 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.