Mountain Migrants: a Survey of the Tibetan Antelope and Wild Yak In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inclusion of Asiatic Mammal Species on Cms Appendices

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals Secretariat provided by the United Nations Environment Programme 14 th MEETING OF THE CMS SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL Bonn, Germany, 14-17 March 2007 CMS/ScC14/Doc.13 Agenda item 6(a) DRAFT PROPOSALS FOR THE INCLUSION OF ASIATIC MAMMAL SPECIES ON CMS APPENDICES (Prepared by the Secretariat) 1. The four draft proposals for the amendment of CMS Appendices attached to this note have been prepared by the Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique and have been submitted by Dr. Pierre Devillers, Scientific Councillor for the European Community and vice-chairman of the Scientific Council. 2. Preparation of these draft proposals is undertaken within the Central Eurasian Aridland Concerted Action and associated Cooperative Action approved by the 8 th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to CMS (Recommendation 8.23), covering threatened migratory large mammals of the temperate and cold deserts, semi-deserts, steppes and associated mountains of Central Asia, the Northern Indian sub-continent, Western Asia, the Caucasus and Eastern Europe. 3. In particular, Rec. 8.23 “encourages Range States and other interested Parties to prepare, in cooperation with the Scientific Council and the Secretariat, the necessary proposals to include in Appendix I or Appendix II threatened species that would benefit from the Action”. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the meeting. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. DRAFT PROPOSAL FOR INCLUSION OF SPECIES ON THE APPENDICES OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS Proposal to add in Appendix I Pantholops hodgsonii Document largely based on the species information provided in IUCN Redlist of Threatened Species database (2006) February 2007 2 1. -

Birding in Ladakh

Birding in Ladakh lthough it is true that the real Ladakh starts where the road ends, we have come to find some very easily accessible areas to help you map your journey to the natural wonders of Athis wilderness in the quickest way, making sure you miss nothing! So bring your binoculars along on your personal search of the wild with our camp naturalist. Ladakh falls between the trans-Himalaya and the southern Tibetan plateau. It’s not misleading when we say you’re at the “Roof of the World” here. In fact, this remote district nestled in the dizzying heights of the Himalaya makes it protected and nearly cut off from even its immediate neighbors- a phenomenon of natural history that creates a sub world of its own.Everything that survives here has undergone millenniums of specialized adaptation and evolution. In the battle for survival, only the hardiest have remained. There is a large group of the Avian world which long dared to cross these mighty heights to visit their spring and autumn migration grounds, adding a mesmerizing diversity to the mix of some resident species which are altitudinal migrants, breeding at high altitudes and descending in winter. This presents a unique opportunity to watch a staggering 310 species of birds in Ladakh. Key stop over sites : Thiksey and Shey Marshes: The area is a must for any bird watcher as it houses a mélange of agricultural fields, marshes and a labyrinth of irrigation channels to reach the river. Explore these wetlands and riverbank along the Indus, which serve as prime habitat. -

Download Download

OPEN ACCESS The Journal of Threatened Taxa fs dedfcated to bufldfng evfdence for conservafon globally by publfshfng peer-revfewed arfcles onlfne every month at a reasonably rapfd rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org . All arfcles publfshed fn JoTT are regfstered under Creafve Commons Atrfbufon 4.0 Internafonal Lfcense unless otherwfse menfoned. JoTT allows unrestrfcted use of arfcles fn any medfum, reproducfon, and dfstrfbufon by provfdfng adequate credft to the authors and the source of publfcafon. Journal of Threatened Taxa Bufldfng evfdence for conservafon globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Onlfne) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Prfnt) Revfew Nepal’s Natfonal Red Lfst of Bfrds Carol Inskfpp, Hem Sagar Baral, Tfm Inskfpp, Ambfka Prasad Khafwada, Monsoon Pokharel Khafwada, Laxman Prasad Poudyal & Rajan Amfn 26 January 2017 | Vol. 9| No. 1 | Pp. 9700–9722 10.11609/jot. 2855 .9.1. 9700-9722 For Focus, Scope, Afms, Polfcfes and Gufdelfnes vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/About_JoTT.asp For Arfcle Submfssfon Gufdelfnes vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/Submfssfon_Gufdelfnes.asp For Polfcfes agafnst Scfenffc Mfsconduct vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/JoTT_Polfcy_agafnst_Scfenffc_Mfsconduct.asp For reprfnts contact <[email protected]> Publfsher/Host Partner Threatened Taxa Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 January 2017 | 9(1): 9700–9722 Revfew Nepal’s Natfonal Red Lfst of Bfrds Carol Inskfpp 1 , Hem Sagar Baral 2 , Tfm Inskfpp 3 , Ambfka Prasad Khafwada 4 , 5 6 7 ISSN 0974-7907 (Onlfne) Monsoon Pokharel Khafwada , Laxman Prasad -

Towards Snow Leopard Prey Recovery: Understanding the Resource Use Strategies and Demographic Responses of Bharal Pseudois Nayaur to Livestock Grazing and Removal

Towards snow leopard prey recovery: understanding the resource use strategies and demographic responses of bharal Pseudois nayaur to livestock grazing and removal Final project report submitted by Kulbhushansingh Suryawanshi Nature Conservation Foundation, Mysore Post-graduate Program in Wildlife Biology and Conservation, National Centre for Biological Sciences, Wildlife Conservation Society –India program, Bangalore, India To Snow Leopard Conservation Grant Program January 2009 Towards snow leopard prey recovery: understanding the resource use strategies and demographic responses of bharal Pseudois nayaur to livestock grazing and removal. 1. Executive Summary: Decline of wild prey populations in the Himalayan region, largely due to competition with livestock, has been identified as one of the main threats to the snow leopard Uncia uncia. Studies show that bharal Pseudois nayaur diet is dominated by graminoids during summer, but the proportion of graminoids declines in winter. We explore the causes for the decline of graminoids from bharal winter diet and resulting implications for bharal conservation. We test the predictions generated by two alternative hypotheses, (H1) low graminoid availability caused by livestock grazing during winter causes bharal to include browse in their diet, and, (H2) bharal include browse, with relatively higher nutrition, to compensate for the poor quality of graminoids during winter. Graminoid availability was highest in areas without livestock grazing, followed by areas with moderate and intense livestock grazing. Graminoid quality in winter was relatively lower than that of browse, but the difference was not statistically significant. Bharal diet was dominated by graminoids in areas with highest graminoid availability. Graminoid contribution to bharal diet declined monotonically with a decline in graminoid availability. -

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-Hðgå-ÅÛ-Hýh-ºiô-;Ým-Mû-Ç+Ô¼-¾-Zçàz-Çeômü

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-hÝh-ºIô-;Ým-mÛ-Ç+ô¼-¾-zÇÀz-Çeômü Tahir Shawl Jigmet Takpa Phuntsog Tashi Yamini Panchaksharam 2 FOREWORD Ladakh is one of the most wonderful places on earth with unique biodiversity. I have the privilege of forwarding the fi eld guide on mammals of Ladakh which is part of a series of bilingual (English and Ladakhi) fi eld guides developed by WWF-India. It is not just because of my involvement in the conservation issues of the state of Jammu & Kashmir, but I am impressed with the Ladakhi version of the Field Guide. As the Field Guide has been specially produced for the local youth, I hope that the Guide will help in conserving the unique mammal species of Ladakh. I also hope that the Guide will become a companion for every nature lover visiting Ladakh. I commend the efforts of the authors in bringing out this unique publication. A K Srivastava, IFS Chief Wildlife Warden, Govt. of Jammu & Kashmir 3 ÇSôm-zXôhü ¾-hÐGÅ-mÛ-ºWÛG-dïm-mP-¾-ÆôG-VGÅ-Ço-±ôGÅ-»ôh-źÛ-GmÅ-Å-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-ŸÛG-»Ûm-môGü ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Å-GmÅ-;Ým-¾-»ôh-qºÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚Å-q-ºhÛ-¾-ÇSôm-zXôh-‚ô-‚Å- qôºÛ-PºÛ-¾Å-ºGm-»Ûm-môGü ºÛ-zô-P-¼P-W¤-¤Þ-;-ÁÛ-¤Û¼-¼Û-¼P-zŸÛm-D¤-ÆâP-Bôz-hP- ºƒï¾-»ôh-¤Dm-qôÅ-‚Å-¼ï-¤m-q-ºÛ-zô-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Ç+h-hï-mP-P-»ôh-‚Å-qôº-È-¾Å-bï-»P- zÁh- »ôPÅü Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚ô-‚Å-qô-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-¾ÛÅ-GŸôm-mÝ-;Ým-¾-wm-‚Å-¾-ºwÛP-yï-»Ûm- môG ºô-zôºÛ-;-mÅ-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-Tm-mÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-BôzÅ-¾-wm-qºÛ-¼Û-zô-»Ûm- hôm-m-®ôGÅ-¾ü ¼P-zŸÛm-D¤Å-¾-ºfh-qô-»ôh-¤Dm-±P-¤-¾ºP-wm-fôGÅ-qºÛ-¼ï-z-»Ûmü ºhÛ-®ßGÅ-ºô-zM¾-¤²h-hï-ºƒÛ-¤Dm-mÛ-ºhÛ-hqï-V-zô-q¼-¾-zMz-Çeï-Çtï¾-hGôÅ-»Ûm-môG Íï-;ï-ÁÙÛ-¶Å-b-z-ͺÛ-Íïw-ÍôÅ- mGÅ-±ôGÅ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-Bôz-Çkï-DG-GÛ-hqôm-qô-G®ô-zô-W¤- ¤Þ-;ÁÛ-¤Û¼-GŸÝP.ü 4 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The fi eld guide is the result of exhaustive work by a large number of people. -

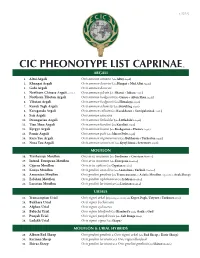

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Royle Safaris Sichuan Mammals Tour Trip Report

In March 2019 Royle Safaris ran our second specialist Sichuan Mammals Tour with a focus on a particularly special species. The trip was run with Martin Royle, Roland Zeidler & Sid Francis as our guides. We visited 3 different locations (covering the rugged bamboo forests of the greater Wolong ecosystem, the high altitude grasslands of Rouergai and the wonderful forests of Tangjiahe. We were very successful with sightings of 44 different species of mammals and over 100 species of birds including Giant Panda, Red Panda, Pallas’s Cat, Chinese Mountain Cat, Indochinese Leopard Cat, Particoloured Flying Squirrel, Golden Snub-nosed Monkey, Chinese Ferret Badger, Eurasian Otter and Chinese Pipistrelle. We ran a second Sichuan’s Mammals Tour (back to back with this one) in April 2019 and we had even more success in some areas. The sightings log for that trip will follow in a few days. We have started to promote our 2020 Sichuan Mammals Tour (with special focus on a particular special species for half of the trip); we have already received many bookings on these two trips. Our first tour for 2020 (9th – 22nd March 2020) has just one place remaining and our second tour for 2020 (25th April – 8th May 2020) which also has only one place remaining. We have also started offering places on another specialist mammal tour of China, visiting Qinghai and the wonderful Valley of the Cats. This tour is for July 2020 (1st – 15th July 2020) and focuses on Snow leopards, Eurasian lynx, Himalayan wolf, Himalayan brown bear, Tibetan antelope, Wild Yak, White-lipped deer, Alpine musk deer, Glover’s pika, Bharal, McNeil’s deer and many more species. -

CAPRA SIBRICA, the ASIATIC IBEX 14.1 the Living Animal 14.1.1

CHAPTER FOURTEEN CAPRA SIBRICA, THE ASIATIC IBEX 14.1 The Living Animal 14.1.1 Zoology The ibex (fi g. 198) is a wild goat with a rather massive built and impres- sive horns. Bucks stand about one metre at the shoulder, females are smaller and less massive. The most impressive feature of the ibex are the scimitar-like curved horns with lengths of 1–1.15 m around the curve; those of the females are smaller. The horns are regularly ridged, lacking the prominent knobs as present in the bezoar goat (see next section) and feral domestic goats. In older bucks the curvature of the horns is somewhat longer: the tips are directed downwards and not backwards. There is no anterior keel and the anterior part of the horn is fl at; the cross-section through the base is almost square. Typical of all goat species is that both sexes bear horns, though those of the females are usually smaller and less massive. Goats, wild as well as domestic, have a short, upright held tail and the males have a beard below the chin. Wild goats, including the markhor, are expert climbers, sure-footed, leaping from ledge to ledge and balancing on nothing more than a pinnacle of rock. They are able to sustain on the most coarse and thorny plants. All wild goats live in large herds up to forty or fi fty individuals; occasional sometimes even much larger assemblages are seen of ibexes. The Asiatic or Siberian ibex is found above the tree line on the steep slopes, inaccessible to most other animals, of the western Himalayas on both sides of the main Himalayan range, and of the mountain ranges of Kashmir and Baltistan. -

Method 2 Q Airgun - Bullet Or Shaft (Circle One) Q Picked Up

Animal _______________________________________ Date Taken ___________ SAFARI CLUB Month / Day / Year INTERNATIONAL Remeasurement? q Yes q No Former Score ________Record No. ______________ q Rifle q Handgun q Muzzleloader q Bow q Crossbow q Shotgun Method 2 q Airgun - Bullet or Shaft (circle one) q Picked Up Entry Form Place Taken _________________________________ ____________________________ For spiral-horned animals. Includes eland, Country State or Province bongo, kudu, nyala, sitatunga, bushbuck, Locality ___________________________________________________________________ addax, blackbuck, markhor and feral goat. (GMU, Mtn Range, Ranch, City, Town) Guide _____________________________________________________________ Hunting Co. ______________________________________________________________ I. Length of Horn L _________ ⁄8 R _________ ⁄8 II. Circumference of Horn L _________ ⁄8 R _________ ⁄8 at Base Hunter ______________________________________________________________________ How you want your name to appear in the Record Book Membership No. _____________________Phone __________________________ E-mail ______________________________________________________________ III. Total Score ⁄8 Address _____________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________ q Anonymous Submission - Members who choose “Anonymous Submission” will have their Record Book ID number replace their name in the Record Book. I certify that, to the best of my knowledge, I took this animal without violating -

High Altitude Survival

High altitude survival Conflicts between pastoralism andwildlif e in the Trans-Himalaya Charudutt Mishra CENTRALE LANDBOUWCATALOGUS 0000 0873 6775 Promotor Prof.Dr .H .H .T .Prin s Hoogleraar inhe tNatuurbehee r ind eTrope n enEcologi eva n Vertebraten Co-promotor : Dr.S .E .Va nWiere n Universitair Docent, Leerstoelgroep Natuurbeheer in de Tropen enEcologi eva nVertebrate n Promotie Prof.Dr .Ir .A .J .Va n DerZijp p commissie Wageningen Universiteit Prof.Dr .J .H . Koeman Wageningen Universiteit Prof.Dr . J.P .Bakke r Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Prof.Dr .A .K .Skidmor e International Institute forAerospac e Survey and Earth Sciences, Enschede High altitude survival: conflicts between pastoralism and wildlife inth e Trans-Himalaya Charudutt Mishra Proefschrift ter verkrijging van degraa d van doctor opgeza g van derecto r magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit prof. dr. ir. L. Speelman, inhe t openbaar te verdedigen opvrijda g 14decembe r200 1 des namiddags te 13:30uu r in deAul a -\ •> Mishra, C. High altitude survival:conflict s between pastoralism andwildlif e inth e Trans-Himalaya Wageningen University, The Netherlands. Doctoral Thesis (2001); ISBN 90-5808-542-2 A^ofZC , "SMO Propositions 1. Classical nature conservation measures will not suffice, because the new and additional measures that have to be taken must be especially designed for those areas where people live and use resources (Herbert Prins, The Malawi principles: clarification of thoughts that underlaythe ecosystem approach). 2. The ability tomak e informed decisions on conservation policy remains handicapped due to poor understanding of the way people use natural resources, and the impacts of such resource use onwildlif e (This thesis). -

(IRP) 2020 Week-9

IASbaba’s Integrated Revision Plan (IRP) 2020 Week-9 CURRENT AFFAIRS QUIZ Q.1) With reference to Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme, which of the statements given below is incorrect? a) It provides loans to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) only. b) It was rolled out as part of the Centre’s Aatmanirbhar package in response to the COVID•19 crisis. c) It has a corpus of ₹41,600 crore and provides fully guaranteed additional funding of up to ₹3 lakh crore. d) None Q.1) Solution (a) The Centre has expanded its credit guarantee scheme for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) to cover loans given to larger firms, as well as to self•-employed people and professionals who have taken loans for business purposes. The Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme was rolled out in May as part of the Centre’s Aatmanirbhar package in response to the COVID•19 crisis. It has a corpus of ₹41,600 crore and provides fully guaranteed additional funding of up to ₹3 lakh crore. Source: https://www.thehindu.com/business/Economy/credit-guarantee-extended-to-larger- firms-self-employed/article32249835.ece Q.2) Which of the following statements about Bal Gangadhar Tilak is/are correct? 1. He founded the Fergusson College in Pune. 2. He was part of the extremist faction of Indian National Congress. 3. He was associated with the Hindu Mahasabha. Select the correct answer using code below a) 1 and 2 b) 2 only c) 1 and 3 only d) 1, 2 ad 3 Q.2) Solution (a) Bal Gangadhar Tilak IASbaba’s Integrated Revision Plan (IRP) 2020 Week-9 He was commonly known as Lokamanya Tilak. -

IUCN Briefing Paper

BRIEFING PAPER September 2016 Contact information updated April 2019 Informing decisions on trophy hunting A Briefing Paper regarding issues to be taken into account when considering restriction of imports of hunting trophies For more information: SUMMARY Dilys Roe Trophy hunting is currently the subject of intense debate, with moves IUCN CEESP/SSC Sustainable Use at various levels to end or restrict it, including through increased bans and Livelihoods or restrictions on carriage or import of trophies. This paper seeks to inform SpecialistGroup these discussions. [email protected] Patricia Cremona IUCN Global Species (such as large antlers), and overlaps with widely practiced hunting for meat. Programme It is clear that there have been, and continue to be, cases of poorly conducted [email protected] and poorly regulated hunting. While “Cecil the Lion” is perhaps the most highly publicised controversial case, there are examples of weak governance, corruption, lack of transparency, excessive quotas, illegal hunting, poor monitoring and other problems in a number of countries. This poor practice requires urgent action and reform. However, legal, well regulated trophy Habitat loss and degradation is a primary hunting programmes can, and do, play driver of declines in populations an important role in delivering benefits of terrestrial species. Demographic change for both wildlife conservation and for and corresponding demands for land for the livelihoods and wellbeing of indigenous development are increasing in biodiversity- and local communities living with wildlife. rich parts of the globe, exacerbating this pressure on wildlife and making the need for viable conservation incentives more urgent. © James Warwick RECOMMENDATIONS and the rights and livelihoods of indigenous and local communities, IUCN calls on relevant decision- makers at all levels to ensure that any decisions that could restrict or end trophy hunting programmes: i.