Division of Law Enforcement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Control of the Value of Black Goldminers' Labour-Power in South

Farouk Stemmet Control of the Value of Black Goldminers’ Labour-Power in South Africa in the Early Industrial Period as a Consequence of the Disjuncture between the Rising Value of Gold and its ‘Fixed Price’ Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Glasgow October, 1993. © Farouk Stemmet, MCMXCIII ProQuest Number: 13818401 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818401 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 GLASGOW UNIVFRSIT7 LIBRARY Abstract The title of this thesis,Control of the Value of Black Goldminers' Labour- Power in South Africa in the Early Industrial Period as a Consequence of the Disjuncture between the Rising Value of Gold and'Fixed its Price', presents, in reverse, the sequence of arguments that make up this dissertation. The revolution which took place in the value of gold, the measure of value, in the second half of the nineteenth century, coincided with the need of international trade to hold fast the value-ratio at which the world's various paper currencies represented a definite weight of gold. -

Project Report 2010-2011

FOOD HABITS AND OVERLAPS BETWEEN LIVESTOCK AND MONGOLIAN SAIGA PROJECT REPORT 2010-2011 Bayarbaatar Buuveibaatar Gundensambuu Gunbat Correspondence: Buuveibaatar Bayarbaatar. PhD Student, Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst 01003, USA [email protected] & Wildlife Conservation Society, Mongolia Program, “Internom” Bookstore 3rd Floor, Ulaanbaatar 211238, Mongolia Abstract The Mongolian saiga (Saiga tatarica mongolica) is listed as a critically endangered antelope in IUCN Red list and their conservation is urgently needed. Recent increases in livestock numbers have potentially reduced the capacity of habitats to sustain saiga because of forage or interference competition. We studied the potential for forage competition between saiga and domestic livestock in Shargyn Gobi, western Mongolia by quantifying diet overlaps using microscopic analysis of fecal samples. We collected 10 fecal samples from each of saiga, goat, sheep, horse, and camels in summer of 2011. We also established 105 plots at sightings of marked saiga antelope in June 2011 to determine vegetation community within saiga range. Each plot was subdivided into 5 adjacent 1 m2 square quadrats and the plants in them were surveyed. Onions or Allium appeared greater proportions in the diet composition of saiga, goat, and sheep. Diet composition of camels consisted mainly from shrubs, whereas Stipa was the dominantly found in the diet of horses. Among twenty-five plant species were recorded in the vegetation plots, Allium sp was the most frequently occurred species. The food habits of Mongolian saiga were quite similar to those of sheep and goats but were different from those of horses and camels. Our results suggest the saiga and sheep/goats would potentially be competitive on pasture as were suggested in similar study on Mongolian gazelle and argali sheep in Mongolia. -

Towards Snow Leopard Prey Recovery: Understanding the Resource Use Strategies and Demographic Responses of Bharal Pseudois Nayaur to Livestock Grazing and Removal

Towards snow leopard prey recovery: understanding the resource use strategies and demographic responses of bharal Pseudois nayaur to livestock grazing and removal Final project report submitted by Kulbhushansingh Suryawanshi Nature Conservation Foundation, Mysore Post-graduate Program in Wildlife Biology and Conservation, National Centre for Biological Sciences, Wildlife Conservation Society –India program, Bangalore, India To Snow Leopard Conservation Grant Program January 2009 Towards snow leopard prey recovery: understanding the resource use strategies and demographic responses of bharal Pseudois nayaur to livestock grazing and removal. 1. Executive Summary: Decline of wild prey populations in the Himalayan region, largely due to competition with livestock, has been identified as one of the main threats to the snow leopard Uncia uncia. Studies show that bharal Pseudois nayaur diet is dominated by graminoids during summer, but the proportion of graminoids declines in winter. We explore the causes for the decline of graminoids from bharal winter diet and resulting implications for bharal conservation. We test the predictions generated by two alternative hypotheses, (H1) low graminoid availability caused by livestock grazing during winter causes bharal to include browse in their diet, and, (H2) bharal include browse, with relatively higher nutrition, to compensate for the poor quality of graminoids during winter. Graminoid availability was highest in areas without livestock grazing, followed by areas with moderate and intense livestock grazing. Graminoid quality in winter was relatively lower than that of browse, but the difference was not statistically significant. Bharal diet was dominated by graminoids in areas with highest graminoid availability. Graminoid contribution to bharal diet declined monotonically with a decline in graminoid availability. -

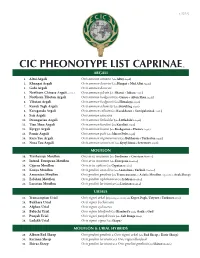

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Of the Chang Tang Wildlife Reserve in Tibet

RANGELANDS 18(3), June 1996 91 Rangelands of the Chang Tang Wildlife Reserve in Tibet Daniel J. Millerand George B. Schaller eastern part of the cious steppes and mountains that Chang Tang Reserve sweep along northern Tibet for almost based on our research in 800 miles east to west. The chang the fall of 1993 and sum- tang, a vast and vigorous landscape mer of 1994. We also comparable in size to the Great Plains discuss conservation of North America, is one of the highest, issues facing the reserve most remote and least known range- and the implications lands of the world. The land is too cold these have for develop- and arid to support forests and agricul- ment, management and ture; vegetation is dominated by cold- conservation. desert grasslands,with a sparse cover of grasses, sedges, forbs and low shrubs. It is one of the world's last Descriptionand great wildernessareas. Location The Chang Tang Wildlife Reserve was established by the Tibetan Located in the north- Autonomous governmentin of the Region western part 1993 to protect Tibet's last, major Tibetan Autonomous wildlife populationsand the grasslands Region (see Map 1), the depend upon. In the wildernessof Reserve they Chang Tang the Chang Tang Reservelarge herdsof encompasses approxi- Tibetan antelope still follow ancient mately 110,000 square trails on their annual migrationroutes to A nomad bundled the wind while Tibetan lady up against miles, (an area about birthing grounds in the far north. Wild herding. of the size Arizona), yaks, exterminated in most of Tibet, and is the second in maintain their last stronghold in the he Chang Tang Wildlife Reserve, area in the world. -

IUCN Briefing Paper

BRIEFING PAPER September 2016 Contact information updated April 2019 Informing decisions on trophy hunting A Briefing Paper regarding issues to be taken into account when considering restriction of imports of hunting trophies For more information: SUMMARY Dilys Roe Trophy hunting is currently the subject of intense debate, with moves IUCN CEESP/SSC Sustainable Use at various levels to end or restrict it, including through increased bans and Livelihoods or restrictions on carriage or import of trophies. This paper seeks to inform SpecialistGroup these discussions. [email protected] Patricia Cremona IUCN Global Species (such as large antlers), and overlaps with widely practiced hunting for meat. Programme It is clear that there have been, and continue to be, cases of poorly conducted [email protected] and poorly regulated hunting. While “Cecil the Lion” is perhaps the most highly publicised controversial case, there are examples of weak governance, corruption, lack of transparency, excessive quotas, illegal hunting, poor monitoring and other problems in a number of countries. This poor practice requires urgent action and reform. However, legal, well regulated trophy Habitat loss and degradation is a primary hunting programmes can, and do, play driver of declines in populations an important role in delivering benefits of terrestrial species. Demographic change for both wildlife conservation and for and corresponding demands for land for the livelihoods and wellbeing of indigenous development are increasing in biodiversity- and local communities living with wildlife. rich parts of the globe, exacerbating this pressure on wildlife and making the need for viable conservation incentives more urgent. © James Warwick RECOMMENDATIONS and the rights and livelihoods of indigenous and local communities, IUCN calls on relevant decision- makers at all levels to ensure that any decisions that could restrict or end trophy hunting programmes: i. -

Is Trophy Hunting of Bharal (Blue Sheep) and Himalayan Tahr Contributing to Their Conservation in Nepal?

Published by Associazione Teriologica Italiana Volume 26 (2): 85–88, 2015 Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy Available online at: http://www.italian-journal-of-mammalogy.it/article/view/11210/pdf doi:10.4404/hystrix-26.2-11210 Research Article Is trophy hunting of bharal (blue sheep) and Himalayan tahr contributing to their conservation in Nepal? Achyut Aryala,∗, Maheshwar Dhakalb, Saroj Panthic, Bhupendra Prasad Yadavb, Uttam Babu Shresthad, Roberta Bencinie, David Raubenheimerf, Weihong Jia aInstitute of Natural and Mathematical Sciences, Massey University, Auckland, New Zealand bDepartment of National Park and Wildlife Conservation, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Government of Nepal, Nepal cDistrict Forest Office, Darchula, Department of Forest, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Government of Nepal, Nepal dInstitute for Agriculture and the Environment, University of Southern Queensland, Australia eSchool of Animal Biology, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, Western Australia, Australia fThe Charles Perkins Centre and Faculty of Veterinary Science and School of Biological Sciences, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia Keywords: Abstract Bharal Himalayan tahr Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve (DHR), the only hunting reserve in Nepal, is famous for trophy hunt- hunting ing of bharal or “blue sheep” (Pseudois nayaur) and Himalayan tahr (Hemitragus jemlahicus). conservation Although trophy hunting has been occurring in DHR since 1987, its ecological consequences are local community poorly known. We assessed the ecological consequences of bharal and Himalayan tahr hunting in revenue DHR, and estimated the economic contribution of hunting to the government and local communit- sex ratio population ies based on the revenue data. The bharal population increased significantly from 1990 to 2011, but the sex ratio became skewed from male-biased (129 Male:100 Female) in 1990 to female-biased (82 Male:100 Female) in 2011. -

Influence of Trophy Harvest on the Population Age Structure of Argali Ovis Ammon in Mongolia

Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 109(3), Sept-Dec 2012 173-176 INFLUENCE OF TROPHY HARVEST ON ARGALI POPULATION INFLUENCE OF TROPHY HARVEST ON THE POPULATION AGE STRUCTURE OF ARGALI OVIS AMMON IN MONGOLIA MICHAEL R. FRISINA1 AND R. MARGARET FRISINA2 1Montana State University Bozeman, Department of Animal and Range Sciences, Bozeman, MT. 59717 USA. Email: [email protected] 2August L. Hormay Wildlands Institute, PO Box 4712, Butte, MT. 59701 USA. To assess the influence of trophy hunting on Mongolian Argali Ovis ammon, we compared the ages of trophy rams (n=64) taken through Mongolia’s legal hunting programme with those of mature rams that died of natural causes (n=116). A two-sample Kolomogorov-Smirnov test indicated that the distributions of the two groups were different (P=0.001). A two-sample t-test indicated the distributional differences were due, at least in part, to differences in the mean ages between the natural deaths and hunter harvested samples (P=0.001); the distributions were not centered at the same value or the means in the two populations differ. Application of the Central Limit Theorem affirms that the distribution of the sample mean ages for natural death and hunter harvested populations will be approximately normal, making the t-test applicable. The mean age for the natural death sample was 8.7 years (range: 7.0–13.0) compared to 9.4 (range: 7.0–13) for the hunter harvested sample. At the 95% confidence level, the true difference in ages between the trophy kills and natural deaths is between 3 months and 1 year. -

Small-Business Owners from Widely Varied Industries

No. 17-71 In the Supreme Court of the United States ________________ WEYERHAEUSER COMPANY, Petitioner, v. UNITED STATES FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE, ET AL., Respondents. ________________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ________________ BRIEF OF SMALL BUSINESS OWNERS AS AMICI CURIAE SUPPORTING RESPONDENTS ________________ Kevin J. Lynch J. Carl Cecere UNIVERSITY OF DENVER Counsel of Record STURM COLLEGE OF LAW CECERE PC ENVIRONMENTAL LAW 6035 McCommas Blvd. CLINIC Dallas, TX 75206 2255 E. Evans Ave. (469) 600-9455 Denver, CO 80208 [email protected] (303) 871-6039 Counsel for Amici Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .................................................................. i Table of Authorities ............................................................. ii Interest of Amici Curiae ..................................................... 1 Introduction and Summary of the Argument .................. 1 Argument ............................................................................. 4 I. Protecting endangered species provides signif- icant economic benefits to small businesses. ............ 4 A. ESA regulations provide small-business opportunities. ....................................................... 4 B. The Service’s experts are an economic asset for many small-businesses. ..................... 16 C. Protection of biodiversity is also essential for the economy as a whole. .............................. 19 II. The Service’s broad, flexible authority to designate -

Herpetofauna Communities and Habitat Conditions in Temporary Wetlands of Upland and Floodplain Forests on Public Lands in North-Central Mississippi

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2007 Herpetofauna Communities and Habitat Conditions in Temporary Wetlands of Upland and Floodplain Forests on Public Lands in North-Central Mississippi Katherine E. Edwards Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td Recommended Citation Edwards, Katherine E., "Herpetofauna Communities and Habitat Conditions in Temporary Wetlands of Upland and Floodplain Forests on Public Lands in North-Central Mississippi" (2007). Theses and Dissertations. 2484. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td/2484 This Graduate Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HERPETOFAUNA COMMUNITIES AND HABITAT CONDITIONS IN TEMPORARY WETLANDS OF UPLAND AND FLOODPLAIN FORESTS ON PUBLIC LANDS IN NORTH-CENTRAL MISSISSIPPI By Katherine Elise Edwards A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Mississippi State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Wildlife and Fisheries Science in the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Mississippi State, Mississippi May 2007 HERPETOFAUNA COMMUNITIES AND HABITAT CONDITIONS IN TEMPORARY WETLANDS OF UPLAND AND FLOODPLAIN FORESTS ON PUBLIC LANDS IN NORTH-CENTRAL MISSISSIPPI By Katherine Elise Edwards Approved: Jeanne C. Jones Kristina C. Godwin Associate Professor of Wildlife and State Director, USDA APHIS Fisheries Wildlife Services (Director of Thesis) Adjunct Faculty of Wildlife and Fisheries (Committee Member) W. Daryl Jones Bruce D. Leopold Assistant Extension Professor of Professor and Head Wildlife and Fisheries Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (Committee Member) (Committee Member) Bruce D. -

Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 112:9-16

This authors' personal copy may not be publicly or systematically copied or distributed, or posted on the Open Web, except with written permission of the copyright holder(s). It may be distributed to interested individuals on request. Vol. 112: 9–16, 2014 DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Published November 13 doi: 10.3354/dao02792 Dis Aquat Org High susceptibility of the endangered dusky gopher frog to ranavirus William B. Sutton1,2,*, Matthew J. Gray1, Rebecca H. Hardman1, Rebecca P. Wilkes3, Andrew J. Kouba4, Debra L. Miller1,3 1Center for Wildlife Health, Department of Forestry, Wildlife and Fisheries, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA 2Department of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Tennessee State University, Nashville, TN 37209, USA 3Department of Biomedical and Diagnostic Sciences, University of Tennessee Center of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA 4Memphis Zoo, Conservation and Research Department, Memphis, TN 38112, USA ABSTRACT: Amphibians are one of the most imperiled vertebrate groups, with pathogens playing a role in the decline of some species. Rare species are particularly vulnerable to extinction be - cause populations are often isolated and exist at low abundance. The potential impact of patho- gens on rare amphibian species has seldom been investigated. The dusky gopher frog Lithobates sevosus is one of the most endangered amphibian species in North America, with 100−200 indi- viduals remaining in the wild. Our goal was to determine whether adult L. sevosus were suscep- tible to ranavirus, a pathogen responsible for amphibian die-offs worldwide. We tested the rela- tive susceptibility of adult L. sevosus to ranavirus (103 plaque-forming units) isolated from a morbid bullfrog via 3 routes of exposure: intra-coelomic (IC) injection, oral (OR) inoculation, and water bath (WB) exposure. -

Matthew Jaremski Gabriel Mathy Working P

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES HOW WAS THE QUANTITATIVE EASING PROGRAM OF THE 1930S UNWOUND? Matthew Jaremski Gabriel Mathy Working Paper 23788 http://www.nber.org/papers/w23788 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 September 2017 The authors would like to thank to David Wheelock, Jonathan Rose, Mark Carlson, Andrew Jalil, Christopher Hanes, Roger Sandilands, Mary Hansen, and seminar audiences at the Social Science History Association, the Cato Monetary Workshop, and the Southern Economic Association Meetings for valuable comments, as well as to Daniel Kirwin for invaluable research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.¸˛ NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2017 by Matthew Jaremski and Gabriel Mathy. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. How was the Quantitative Easing Program of the 1930s Unwound? Matthew Jaremski and Gabriel Mathy NBER Working Paper No. 23788 September 2017 JEL No. E32,E58,N12 ABSTRACT Outside of the recent past, excess reserves have only concerned policymakers in one other period: the Great Depression. The data show that excess reserves in the 1930s were never actively unwound through a reduction in the monetary base. Nominal economic growth swelled required reserves while an exogenous reduction in monetary gold inflows due to war embargoes in Europe allowed excess reserves to naturally decline towards zero.