This Pharaoh's Painted Tomb Was Missing Its Mummy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Functions and Uses of Egyptian Myth Fonctions Et Usages Du Mythe Égyptien

Revue de l’histoire des religions 4 | 2018 Qu’est-ce qu’un mythe égyptien ? Functions and Uses of Egyptian Myth Fonctions et usages du mythe égyptien Katja Goebs and John Baines Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rhr/9334 DOI: 10.4000/rhr.9334 ISSN: 2105-2573 Publisher Armand Colin Printed version Date of publication: 1 December 2018 Number of pages: 645-681 ISBN: 978-2-200-93200-8 ISSN: 0035-1423 Electronic reference Katja Goebs and John Baines, “Functions and Uses of Egyptian Myth”, Revue de l’histoire des religions [Online], 4 | 2018, Online since 01 December 2020, connection on 13 January 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/rhr/9334 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/rhr.9334 Tous droits réservés KATJA GOEBS / JOHN BAINES University of Toronto / University of Oxford Functions and Uses of Egyptian Myth* This article discusses functions and uses of myth in ancient Egypt as a contribution to comparative research. Applications of myth are reviewed in order to present a basic general typology of usages: from political, scholarly, ritual, and medical applications, through incorporation in images, to linguistic and literary exploitations. In its range of function and use, Egyptian myth is similar to that of other civilizations, except that written narratives appear to have developed relatively late. The many attested forms and uses underscore its flexibility, which has entailed many interpretations starting with assessments of the Osiris myth reported by Plutarch (2nd century AD). Myths conceptualize, describe, explain, and control the world, and they were adapted to an ever-changing reality. Fonctions et usages du mythe égyptien Cet article discute les fonctions et les usages du mythe en Égypte ancienne dans une perspective comparatiste et passe en revue ses applications, afin de proposer une typologie générale de ses usages – applications politiques, érudites, rituelles et médicales, incorporation dans des images, exploitation linguistique et littéraire. -

G:\Lists Periodicals\Periodical Lists B\BIFAO.Wpd

Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale Past and present members of the staff of the Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Stelae, Reliefs and Paintings, especially R. L. B. Moss and E. W. Burney, have taken part in the analysis of this periodical and the preparation of this list at the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford This pdf version (situation on 14 July 2010): Jaromir Malek (Editor), Diana Magee, Elizabeth Fleming and Alison Hobby (Assistants to the Editor) Clédat in BIFAO i (1901), 21-3 fig. 1 Meir. B.2. Ukh-hotep. iv.250(8)-(9) Top register, Beja herdsman. Clédat in BIFAO i (1901), 21-3 fig. 2 Meir. B.2. Ukh-hotep. iv.250(4)-(5) Lower part, Beja herdsman. Clédat in BIFAO i (1901), 21-3 fig. 3 Meir. B.2. Ukh-hotep. iv.250(8)-(9) III, Beja holding on to boat. Salmon in BIFAO i (1901), pl. opp. 72 El-Faiyûm. iv.96 Plan. Clédat in BIFAO i (1901), 88-9 Meir. Miscellaneous. Statues. iv.257 Fragment of statue of Ukh-hotep. Clédat in BIFAO i (1901), 89 [4] El-Qûs.îya. (Cusae) iv.258A Block of Djehutardais, probably Dyn. XXX. Clédat in BIFAO i (1901), 90 [top] Text El-Qûs.îya. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Stelae, Reliefs and Paintings Griffith Institute, Sackler Library, 1 St John Street, Oxford OX1 2LG, United Kingdom [email protected] 2 iv.258 Fragment of lintel. Clédat in BIFAO i (1901), 92-3 Cartouches and texts Gebel Abû Fôda. -

Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign

oi.uchicago.edu STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION * NO.42 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Thomas A. Holland * Editor with the assistance of Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ROAD TO KADESH A HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE BATTLE RELIEFS OF KING SETY I AT KARNAK SECOND EDITION REVISED WILLIAM J. MURNANE THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION . NO.42 CHICAGO * ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-63725 ISBN: 0-918986-67-2 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 1985, 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1990. Printed in the United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS List of M aps ................................ ................................. ................................. vi Preface to the Second Edition ................................................................................................. vii Preface to the First Edition ................................................................................................. ix List of Bibliographic Abbreviations ..................................... ....................... xi Chapter 1. Egypt's Relations with Hatti From the Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign ...................................................................... ......................... 1 The Clash of Empires -

A New Approach to the Interpretation As to the Function of the Elevated Beds Discovered at Deir El-Medina

A NEW APPROACH OF IDENTIFING THE FUNCTION OF THE ELEVATED BEDS AT DEIR EL-MEDINA by MICHELLE LESLEY BROOKER A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY (B) Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity The University of Birmingham 11/06/09 June 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This research consists of a different approach to the investigation of the elevated beds at Deir el-Medina. It identifies the underlining factors considered during their construction, where they were positioned, how they were orientated and what the surviving iconographies suggested about their original usage. It concludes with identifying the front rooms at Deir el-Medina as gardens. The frontal room is where the elevated beds were positioned and therefore link to the gardens symbolic meaning of resurrection and the afterlife. The elevated beds were orientated to symbolize the deceases’ connection with Re and Osiris. It also signifies a change after the Amarna period with an influx in Osiris worship. The iconographies surviving upon the elevated beds convey the deceased being reborn within the field of reeds signifying that the elevated beds were possibly used for altar purposes. -

119 Original Article the GOLDEN SHRINES of TUTANKHAMUN

id9070281 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies "EJARS" An International peer-reviewed journal published bi-annually Volume 2, Issue 2, December - 2012: pp: 119-130 www. ejars.sohag-univ.edu.eg Original article THE GOLDEN SHRINES OF TUTANKHAMUN AND THEIR INTENDED BURIAL PLACE Soliman, R. Lecturer, Tourism guidance dept., Faculty of Archaeology & Tourism guidance, Misr Univ. for Sciences & Technology, 6th October city, Egypt E-mail: [email protected] Received 3/5/2012 Accepted 12/10/2012 Abstract The most famous tomb at the Valley of the Kings, KV 62 housed so far the most intact discovery of royal funerary treasures belonging to the eighteenth dynasty boy-king Tutankhamun. The tomb has a simple architectural plan clearly prepared for a non- royal burial. However, the hastily death of Tutankhamun at a young age caused his interment in such unusually small tomb. The treasures discovered were immense in number, art finesse and especially in the amount of gold used. Of these treasures the largest shrine of four shrines laid in the burial chamber needed to be dismantled and reassembled in the tomb because of its immense size. Clearly the black marks on this shrine helped in the assembly and especially the orientation in relation to the burial chamber. These marks are totally incorrect and prove that Tutankhamun was definitely intended to be buried in another tomb. Keywords: KV62, WV23, Golden shrines, Tutankhamun, Burial chamber, Orientation. 1. Introduction Tutankhamun was only nine and the real cause of his death remains years old when he got to throne; at that enigmatic. -

The Wooden Shabti of Amenemhat in the Brooklyn Museum 39

the wooden shabti of amenemhat in the brooklyn museum 39 REUSED OR RESTORED? THE WOODEN SHABTI OF AMENEMHAT IN THE BROOKLYN MUSEUM Edward Bleiberg Brooklyn Museum The Brooklyn Museum Egyptian collection in- The Date of the Shabtis and Box cludes two very fine shabtis of a certain Ame- nemhat, an official who lived during the 18th At some point after the publication of James’s Dynasty. In addition to a limestone shabti (fig. 1, Corpus, the departmental records in the Brooklyn Brooklyn 50.128) and a wooden shabti (fig. 2, Museum were altered to date these objects to the Brooklyn 50.129), there is a wooden box (figs. “Reign of Thutmose IV to Akhenaten.” Though 3-6, Brooklyn, 50.130). The Museum purchased no explanation was included with the change, it is these three objects from a New York dealer. They clear why it was made. The limestone shabti holds were published together in the auction catalogue a hoe and a basket in each hand. Schneider’s study of the Mansoor Collection in 1947, the first pub- of shabtis indicates that this feature of shabtis first lication of these objects known to me.1 The cata- appeared either in the reign of Thutmose IV or logue’s author asserts a connection between these Amenhotep III.6 Moreover, the wooden shabti’s objects and Theban Tomb 82, the burial spot for face, with its narrow, almond-shaped eyes, lower the Scribe of the Counting of the Grain of Amun, inner canthi of the eyes, and a distinctly carved Amenemhat, who lived during the reign of Thut- lip line, suggests a date in the reign of Amenhotep mose III.2 This connection was affirmed by John III. -

The Solar Eclipses of the Pharaoh Akhenaten

IN ORIGINAL FORM PUBLISHED IN: arXiv: 2004.12952 [physics.hist-ph] Habilitation at the University of Heidelberg v2: 20th July 2020 The Solar Eclipses of the Pharaoh Akhenaten Emil Khalisi 69126 Heidelberg, Germany e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. We suggest an earlier date for the accession of the pharaoh Akhenaten of the New Kingdom in Egypt. His first year of reign would be placed in 1382 BCE. This conjecture is based on the possible witness of three annular eclipses of the sun during his lifetime: in 1399, 1389, and 1378 BCE. They would explain the motivefor his worshipof the sun that left its mark onlater religious communities. Evidence from Akhenaten’s era is scarce, though some lateral dependencies can be disentangled on implementing the historical course of the subsequent events. Keywords: Solar eclipse, Astronomical dating, Akhenaten, New Kingdom, Egypt. 1 Introduction here. Though there are many reasons to refrain from this method for dates before 700 BCE, we argue that the average The flourishing time of the 18th to 20th dynasty of the Egyp- ∆T is sufficient to satisfy the timeline. The exact position of tian pharaohs, the so-called “New Kingdom”, is not well es- the central tracks is not required to suit our revised course tablished. Traditionally it is placed roughly between 1550 of the historical cornerstones. and 1070 BCE. In the public awareness this era of ancient Egypt is known best, since most people associate with it the “classic pharaonic etiquette”. Memphis near today’s Cairo 2 Worship of the Sun was the administrative center in the very old times, while The adoration of the most important luminary in the sky Thebes about 650 km farther to the south remained an im- played a central role for the old Egyptians, in religion as portant residence of the monarchs. -

WHO WAS WHO AMONG the ROYAL MUMMIES by Edward F

THE oi.uchicago.edu ORIENTAL INSTITUTE NEWS & NOTES NO. 144 WINTER 1995 ©THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO WHO WAS WHO AMONG THE ROYAL MUMMIES By Edward F. Wente, Professor, The Oriental Institute and the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations The University of Chicago had an early association with the mummies. With the exception of the mummy of Thutmose IV, royal mummies, albeit an indirect one. On the Midway in the which a certain Dr. Khayat x-rayed in 1903, and the mummy area in front of where Rockefeller Chapel now stands there of Amenhotep I, x-rayed by Dr. Douglas Derry in the 1930s, was an exhibit of the 1893 World Columbian Exposition known none of the other royal mummies had ever been radiographed as "A Street in Cairo." To lure visitors into the pavilion a plac until Dr. James E. Harris, Chairman of the Department of Orth ard placed at the entrance displayed an over life-sized odontics at the University of Michigan, and his team from the photograph of the "Mummy of Rameses II, the Oppressor of University of Michigan and Alexandria University began x the Israelites." Elsewhere on the exterior of the building were raying the royal mummies in the Cairo Museum in 1967. The the words "Royal Mummies Found Lately in Egypt," giving inadequacy of Smith's approach in determining age at death the impression that the visitor had already been hinted at by would be seeing the genuine Smith in his catalogue, where mummies, which only twelve he indicated that the x-ray of years earlier had been re Thutmose IV suggested that moved by Egyptologists from a this king's age at death might cache in the desert escarpment have been older than his pre of Deir el-Bahri in western vious visual examination of the Thebes. -

How to Plan an Unforgettable Journey in Egypt (Pdf

1 | P a g e How to Plan an Unforgettable Journey in EGYPT Kenn Laya Director North America – EGYPT Tourism USA – New York, New York CEO / Product Development – Vuitton Travel & Luxury Lifestyle – New York, New York Edited By Maria Koehmstedt Cover Photography & Design Charls Lamber Contributor / Ferskov Communications 2 | P a g e To all the people of Egypt, this e-book is for you. By writing "How to Plan an Unforgettable Journey in EGYPT", it is my hope that the many people who read this work come to realize just how amazing it is to visit your incredible country. May they come to see your bountiful sites for themselves and then send their friends. And when they are there, it is my hope that they meet as many of you as is possible during their journey so that when they return, like myself, they can proudly say "I have friends in Egypt." To all of you who I already know in Egypt, and to all of you I have yet to meet, forever you will remain in my heart, as my friends. 3 | P a g e An Egyptian Journey immerses travelers in more than 7,000 years of history – ancient Egypt to the Roman Empire, Islamic dynasties to modern metropolises. With vast and beautiful deserts, fresh oases, simple villages, chaotic metropolises, tranquil Red Sea resorts, the palm-lined Nile and awe- inspiring, sand-swathed monuments, there’s a place for all personalities of traveler. While the country comprises a mixture of different cultures and religions, a unifying and omnipresent sense of hospitality runs deep in the blood of every Egyptian – a warmness toward one another and a kind embrace to all who visit her. -

DSFRA IKEN Report Template

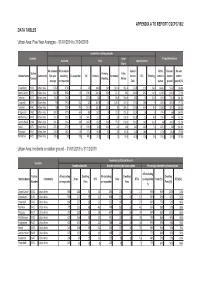

APPENDIX A TO REPORT CSCPC/19/2 DATA TABLES Urban Area: Five-Year Averages – 01/04/2014 to 31/04/2019 Incidents on station grounds Location False Pump Attendances Overview Fires Special Service Alarm All incidents All incidents Special All by On own On own Station Primary: False Station Name Community five-year excluding Co-responder All Primary Secondary Service RTC Flooding station's station station Number Dwelling Alarms average co-responder Calls pumps ground ground (%) Greenbank KV50 Urban Area 878.6 878.6 0 245 104.6 56.6 140.4 361.4 271.8 21.6 24.6 1424.8 974.2 68.4% Danes Castle KV32 Urban Area 832.6 830.8 1.8 198.8 126.4 56.6 72.4 385 248.4 29.2 14.8 1090.6 849.4 77.9% Torquay KV17 Urban Area 744.8 744.8 0 207.8 111 59 96.8 306.8 230 36 15.8 919.8 776.4 84.4% Crownhill KV49 Urban Area 742 741.8 0.2 227 100.6 43 126.4 337.4 177.4 28.6 9 878.4 680.6 77.5% Taunton KV61 Urban Area 734 733.4 0.6 227.8 132.8 56.6 95 284.6 221.6 65.4 8.4 1038.8 901.8 86.8% Bridgwater KV62 Urban Area 584.2 577.6 6.6 160 88.2 38 71.8 231.8 192.4 56 8 774.4 666 86.0% Middlemoor KV59 Urban Area 537.6 535.8 1.8 144.2 91.2 33 53 239.6 153.8 51 8.8 724.4 444 61.3% Camels Head KV48 Urban Area 491.6 491.2 0.4 162.8 85.2 50.4 77.6 178.6 150.2 16.6 11.8 638 390.2 61.2% Yeovil KV73 Urban Area 471.6 471.6 0 139.6 78.6 34.8 61 191 141 46.8 7.4 674.2 569 84.4% Plympton KV47 Urban Area 218.4 204.4 14 57.8 34.8 12 23 87.8 72.4 18.6 3 170.6 135.8 79.6% Plymstock KV51 Urban Area 185.8 185 0.8 48.4 27.4 12 21 76.8 60.6 12.6 2.6 165.4 123.8 74.8% Urban Area: Incidents on -

Collège De Franceinstitut Français Chaire

www.egyptologues.net Collège de FranceInstitut français Chaire "Civilisation de l'Égypte pharaonique : d'archéologie orientale archéologie, philologie, histoire" Bulletin d'Information Archéologique BIA www.egyptologues.net XLI Janvier - Juin 2010 Le Caire - Paris 2010 Système de translittération des mots arabes consonnes voyelles Ce semestre a été relativement riche en expositions. En Égypte avec une rétrospective consacrée à Abû Simbil à la Bibliotheca alexandrina, une exposition ludique au musée du Caire, combinant jeux de lego, puzzles et maquettes, une troisième, enfin, dédiée à Ippolito Rosellini. Aux États- Unis, Toutânkhamon, momies et Cléopâtre attirent à nouveau de nombreux visiteurs, tandis que Zurich présente une collection de chats et de crocodiles. Les fouilles et découvertes, dont certaines fort importantes sont toujours présentées à travers le prisme du discours officiel, qui ne laisse guère de place à leurs inventeurs, quand il ne se transforme pas en mise en scène de résultats illusoires. On retiendra toutefois d’importants travaux, comme ceux de Tell ed-Dab‘a ou du cimetière des ouvriers de Gîza, la découverte de la pyramide de la reine Behenou ou de la tombe de Ptahmes à Saqqara, les recherches menées à Dionysias… La presse insiste beaucoup sur le dégagement du grand dromos de Louqsor, dont le CSA veut faire une vitrine, mais aussi sur les thèmes de polémique habituels. Au premier rang figure la politique de restitution d’objets, dont le Secrétaire général a fait son principal cheval de bataille. Un colloque international de deux jours a servi de tribune internationale pour exiger que la convention ratifiée en 1970 par l’Unesco devienne rétroactive. -

Risk Assessment of Flash Floods in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt

京都大学防災研究所年報 第 60 号 B 平成 29 年 DPRI Annuals, No. 60 B, 2017 Risk Assessment of Flash Floods in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt Yusuke OGISO(1), Tetsuya SUMI, Sameh KANTOUSH, Mohammed SABER and Mohammed ABDEL-FATTAH(1) (1) Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University Synopsis Flash floods unavoidably affect various archaeological sites in Egypt, through increased frequency and severity of extreme events. The Valley of the Kings (KV) is a UNESCO World Heritage site with more than thirty opened tombs. Recently, most of these tombs have been damaged and inundated after 1994 flood. Therefore, KV mitigation strategy has been proposed and implemented with low protection wall surrounding tombs. The present study focuses on the evaluation and risk assessment of the current mitigation measures especially under extreme flood events. Two dimensional hydrodynamic model combined with rainfall runoff modeling by using TELEMAC-2D to simulate the present situation without protection wall and determine the risk of 1994 flood. The results revealed that the current mitigation measures are not efficient. Based on the simulation scenarios, risk of flash floods is assessed, and the more efficient mitigation measurements are proposed. Keywords: Flash floods, The Valley of the Kings, TELEMAC-2D, Mitigation measures 1. Introduction Recently, most of these tombs have been damaged and inundated after 1994 flood. In response to this Egypt is one of arid and semiarid Arabian flood event, the American Research Center in Egypt countries that faces flash floods in the coastal and (ARCE) hired an interdisciplinary team of Nile wadi systems. Wadi is a dry riverbed that can consultants to prepare a flood-protection plan.