2011-080/081/082/083

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interstate Bridge Replacement Program December 2019 Progress Report

Interstate Bridge Replacement Program December 2019 Progress Report December 2019 Progress Report i This page intentionally left blank. ii Interstate Bridge Replacement Program December 2, 2019 (Electronic Transmittal Only) The Honorable Governor Inslee The Honorable Kate Brown WA Senate Transportation Committee Oregon Transportation Commission WA House Transportation Committee OR Joint Committee on Transportation Dear Governors, Transportation Commission, and Transportation Committees: On behalf of the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) and the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), we are pleased to submit the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program status report, as directed by Washington’s 2019-21 transportation budget ESHB 1160, section 306 (24)(e)(iii). The intent of this report is to share activities that have lead up to the beginning of the biennium, accomplishments of the program since funding was made available, and future steps to be completed by the program as it moves forward with the clear support of both states. With the appropriation of $35 million in ESHB 1160 to open a project office and restart work to replace the Interstate Bridge, Governor Inslee and the Washington State Legislature acknowledged the need to renew efforts for replacement of this aging infrastructure. Governor Kate Brown and the Oregon Transportation Commission (OTC) directed ODOT to coordinate with WSDOT on the establishment of a project office. The OTC also allocated $9 million as the state’s initial contribution, and Oregon Legislative leadership appointed members to a Joint Committee on the Interstate Bridge. These actions demonstrate Oregon’s agreement that replacement of the Interstate 5 Bridge is vital. As is conveyed in this report, the program office is working to set this project up for success by working with key partners to build the foundation as we move forward toward project development. -

Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory Report

Report to the Washington State Legislature Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory December 2017 Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory Errata The Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory published to WSDOT’s website on December 1, 2017 contained the following errata. The items below have been corrected in versions downloaded or printed after January 10, 2018. Section 4, page 62: Corrects the parties to the tolling agreement between the States—the Washington State Transportation Commission and the Oregon Transportation Commission. Miscellaneous sections and pages: Minor grammatical corrections. Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory | December 2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary. .1 Section 1: Introduction. .29 Legislative Background to this Report Purpose and Structure of this Report Significant Characteristics of the Project Area Prior Work Summary Section 2: Long-Range Planning . .35 Introduction Bi-State Transportation Committee Portland/Vancouver I-5 Transportation and Trade Partnership Task Force The Transition from Long-Range Planning to Project Development Section 3: Context and Constraints . 41 Introduction Guiding Principles: Vision and Values Statement & Statement of Purpose and Need Built and Natural Environment Navigation and Aviation Protected Species and Resources Traffic Conditions and Travel Demand Safety of Bridge and Highway Facilities Freight Mobility Mobility for Transit, Pedestrian and Bicycle Travel Section 4: Funding and Finance. 55 Introduction Funding and Finance Plan Evolution During -

Frog Ferry Presentation

Frog Ferry Portland-Vancouver Passenger Water Taxi Service Frog= Shwah-kuk in the Chinookan Tribal Language, Art: Adam McIssac CONFIDENTIAL-Susan Bladholm Version 2018 Q1 Canoes and Frog Mythology on the Columbia & Willamette Rivers The ability to travel the waters of the Columbia and Willamette rivers has allowed people to become intertwined through trade and commerce for centuries by canoe. The journal entries of Lewis and Clark in 1805 described the shores of the Columbia River as being lined with canoes elaborately carved from cedar trees. The ability to navigate these waterways gave the Chinook people control over vast reaches of the Columbia River basin for hundreds of years. The area surrounding the Columbia and Willamette rivers is steeped in a rich mythology told to us through early ethnographers who traveled the river documenting Native American inhabitants and their culture. According to Chinookan mythology, Frog (Shwekheyk in Chinook language), was given the basics of weavable fiber by his relatives, Snake and omnipotent Coyote. With this fiber, Frog was given the task of creating the cordage for the weaving of the first fishing net. With this net, made from fibers of nettle plants, Frog had made it possible for the new human beings to catch their first salmon. Coyote tested the net, with the guidance and wisdom of his three sisters, thereby establishing the complex set of taboos associated with the catching of the first salmon of the season. The Chinook people would never eat or harm Frog for his association to them would always protect him. That is why you should always step around frogs and never over them. -

Transit Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement

I N T E R S TAT E 5 C O L U M B I A R I V E R C ROSSING Transit Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement December 2010 Title VI The Columbia River Crossing project team ensures full compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by prohibiting discrimination against any person on the basis of race, color, national origin or sex in the provision of benefits and services resulting from its federally assisted programs and activities. For questions regarding WSDOT’s Title VI Program, you may contact the Department’s Title VI Coordinator at (360) 705-7098. For questions regarding ODOT’s Title VI Program, you may contact the Department’s Civil Rights Office at (503) 986- 4350. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Information If you would like copies of this document in an alternative format, please call the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) project office at (360) 737-2726 or (503) 256-2726. Persons who are deaf or hard of hearing may contact the CRC project through the Telecommunications Relay Service by dialing 7-1-1. ¿Habla usted español? La informacion en esta publicación se puede traducir para usted. Para solicitar los servicios de traducción favor de llamar al (503) 731-4128. Cover Sheet Transit Technical Report Columbia River Crossing Submitted By: Elizabeth Mros-O’Hara, AICP Kelly Betteridge Theodore Stonecliffe, P.E. This page left blank intentionally. Interstate 5 Columbia River Crossing i Transit Technical Report for the Final Environmental Impact Statement TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background .................................................................................................................................................. -

White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Supplemental Draft EIS I

ODOT Key No.: 21280 This page intentionally left blank. This page intentionally left blank. Notice of Document Availability This Supplemental Draft EIS is available for review at the following locations: Port of Hood River (by appointment) 1000 E. Port Marina Drive Hood River, OR 97031 Note: Washington residents can contact the Port to schedule an appointment to view the document in Klickitat County White Salmon Valley Community Library (limited services during the COVID-19 pandemic) 77 NE Wauna Avenue White Salmon, WA 98672 Stevenson Community Library (limited services during the COVID-19 pandemic) 120 NW Vancouver Avenue Stevenson, WA 98648 These documents are also available on the Project website: https://portofhoodriver.com/bridge/bridge-replacement- project/. At the time of publication, Port of Hood River offices are closed due to COVID-19. If you would like to review a hard copy of the Supplemental Draft EIS, please contact the Port at [email protected] or 541-386-1645 to make arrangements for review of the hard copy. The Supplemental Draft EIS can also be viewed at the White Salmon Valley Community Library and the Stevenson Community Library which are open with limited services during the COVID-19 pandemic. How to Submit Comments Written comments on the Supplemental Draft EIS can be submitted during the public comment period (November 20, 2020, through January 4, 2021) by email to [email protected] or regular mail to: Hood River Bridge Supplemental Draft EIS Kevin Greenwood Port of Hood River 1000 E. Port Marina Drive Hood River, OR 97031 Comments can be submitted orally and in writing at the public hearing for the Supplemental Draft EIS on December 3, 2020. -

FY 2010-11 Unified Planning Work Program

FY 2010-11 Unified Planning Work Program Transportation Planning in the Portland/Vancouver Metropolitan Area Metro Tualatin Hills Parks & Recreation City of Damascus City of Milwaukie City of Portland City of Wilsonville (SMART) Clackamas County Multnomah County Washington County TriMet Oregon Department of Transportation Southwest Washington Regional Transportation Council Adopted April 15, 2010 FY 2010-11 Unified Planning Work Program Transportation Planning in the Portland/Vancouver Metropolitan Area Metro Tualatin Hills Parks & Recreation City of Damascus City of Milwaukie City of Portland City of Wilsonville (SMART) Clackamas County Multnomah County Washington County TriMet Oregon Department of Transportation Southwest Washington Regional Transportation Council This Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP) has been financed in part through grants from the Federal Highway Administration, Federal Transit Administration, and the Oregon Department of Transportation. The views expressed in this UPWP do not necessarily represent the views of these agencies. Table of Contents Page Overview i Metropolitan Portland Map iv Self-Certification Resolution v Metro Projects I. Transportation Planning Regional Transportation Planning* .............................................................................. 1 Best Design Practices in Transportation ...................................................................... 7 Making the Greatest Place Transportation Support* .................................................. 10 Transportation System Management -

Hood River Bridge Replacement Environmental Studies, Design and Permit Assistance APRIL 25, 2018 April 25, 2018

CONSULTANT SERVICES FOR Hood River Bridge Replacement Environmental Studies, Design and Permit Assistance APRIL 25, 2018 April 25, 2018 ATTN: Dale Robins Southwest Washington Regional Transportation Council (RTC) 1300 Franklin Street, 4th Floor Vancouver, Washington 98660 Re: Response to RFP Consultant Services for Hood River Bridge Replacement Environmental Studies, Design and Permit Assistance Dear Mr. Dale Robins and Selection Committee, For nearly 95 years, travelers have crossed the Columbia River using the Hood River Bridge, which connects Hood River, Oregon and the communities of White Salmon and Bingen in Washington state. While the travelers are diverse - farmer, hiker, trucker, tugboat operator, windsurfer - their need is the same: a safe, reliable connection between Oregon and Washington. Today, the Hood River Bridge is failing to meet modern transportation demands: deteriorating bridge members, combined with dimensional and weight restrictions for trucks, hamper the structure’s effectiveness and, quite possibly, the regional economy. The replacement of the bridge is a critical transportation improvement needed to support the interstate travel of motorized vehicles, pedestrians and bicyclists, and marine freight transport, which have significant local and regional economic and quality of life benefits. In 1999, a campaign to replace the existing bridge began, which then culminated into the 2003 Draft EIS, which was completed by Parsons Brinkerhoff now WSP. Following the Draft EIS, the firm conducted a Bridge TS&L study. From -

Robert Barnard

Robert Barnard Professional Experience: TriMet, Portland, Oregon Portland-Milwaukie Light Rail Transit Project Director 2008 to present Has primary responsibility for all aspects of project development and delivery, including final design and construction contracts. Manages staff responsible for administration of all design and construction contracts. Responsible for internal/external communications regarding project issues, and coordination with third parties. Monitors and reports cost and schedule status, change control and claims administration. Represents project to outside agencies and interests including the Federal Transit Administration, the U.S. Department of Transportation, and state and local governments. Has executive level role in negotiations and dispute resolution with contractors. Reports to the Executive Director, Capital Project Division. Mall Light Rail Project Design/Construction Director 2007 to 2009 Held primary responsibility for all contracts in $220 million Mall project, including the CM/GC civil/trackwork/systems contract.. Managed staff responsible for administration of all Mall contracts. Responsible for internal/external communications regarding project issues, and coordination with third parties. Monitored and reported cost and schedule status, change control and claims administration. Had top management level role in negotiations/dispute resolution with contractors. City of Portland, Office of Transportation, Portland, Oregon Project Manager 1992 to 2006 Responsible for successful delivery of large, complex, -

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law (Columbia River Crossing Project) 1

Exhibit B Metro Council Resolution No. 11-4280 Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law South/North Corridor Land Use Final Order Columbia River Crossing Project Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law (Columbia River Crossing Project) 1 1. Introduction 1.1 Nature of the Metro Council's Action This action adopts a Land Use Final Order (LUFO) for the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) Project, which is an element of the larger South/North Corridor Project. The action is taken pursuant to Oregon Laws 1996 (Special Session), Chapter 12 (referred to herein as "House Bill 3478" or "the Act"), which directs the Metro Council (Council) to issue LUFOs establishing the light rail route, light rail stations, park-and-ride lots and maintenance facilities, and any highway improvements to be included in the South/North Project, including their locations (i.e. the boundaries within which these facilities and improvements may be located). 1 This LUFO is the fifth in a series of LUFOs the Council has adopted for the South/North Project. The previously adopted LUFOs are as follows: • On July 23, 1998, the Metro Council adopted Resolution No. 98-2673 (the 1998 LUFO), establishing the initial light rail route, stations, lots and maintenance facilities and the highway improvements, including their locations, for the South/North Project. • On October 28, 1999, the Metro Council adopted Resolution No. 99-2853A (the 1999 LUFO), amending the 1998 LUFO to reflect revisions for that portion of the South/North Project extending from the Steel Bridge northward to the Portland Metropolitan Exposition Center (Expo Center), primarily along Interstate Avenue. -

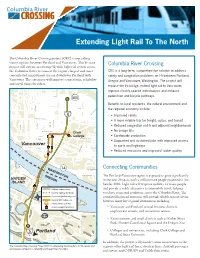

Extending Light Rail to the North

PHILADELPHIA THOMPSON SR-501 SUNSET -SYL V ERWIN O REIGER MEMORIAL AN SCHOLLS FERR SR-501 Y SUNSET PA TT SKYLINE ON WILLAMETTE SHA TTUCK T S HELENS YEON LOWER RIVER LOWER HUMPHREY POR TLAND 41ST W DOSCH SE ARD 36TH COLUMBIA LAKESHORE NICOLAI 31ST V BLISS AUGHN 93RD 1 19TH The Columbia River Crossing project(CRC) is expanding transit options between Portland and Vancouver. This bi-state project will extend an existing 52-mile light rail system across the Columbia River to connect the region’s largest and most concentrated employment area in downtown Portland with Vancouver. This extension will improve connections, reliability 23RD and travel times for riders. VIST A LOMBARD GREELEY HAYDEN ISLAND The Columbia River Crossing Project (CRC) is expanding transit options in Vancouver and will improve connections, reliability and travel times for riders. LAKESHORE 21ST 21ST W BROAD N MARINE DR MARINE N FRONT SIMPSON 94TH A N JANTZEN N Vancouver Y GOING 16TH N H BERNIE GREELEY A 18TH Y D A 109TH E VE LOVEJOY N I S L I405 A N 6TH D 11TH 11TH D LINCOLN R R FOU KAUFFMAN 9TH L 3RD 4TH LINCOLN B PLAIN TH 13TH ST 13TH 15TH ST 8TH ST 8TH T NAI Portland 149TH BARBUR 45TH O 139TH MCLOUGHLIN BL UNION ALDER VD L KEL HARBOR OREGON N T O N MARINE DR MARINE N M Y A H A COLUMBI N W A WASHINGTON ST HOOD W K MAIN ST I5 I S T ASHING VD L 39TH A N POR DELL Highway Improvements D BROADW Existing Highway and Bridge AY ST Proposed Light Rail Alignment ST 17TH Existing MAX Yellow Line HAZEL Proposed Park and Ride Proposed Light Rail Stations D L MARQUAM B R TLAND VD -

COMPLAINT for DECLARATORY and INJUNCTIVE RELIEF - Page 1 of 39 Case 3:12-Cv-01181 Document 1 Filed 07/02/12 Page 2 of 39 Page ID#: 2

Case 3:12-cv-01181 Document 1 Filed 07/02/12 Page 1 of 39 Page ID#: 1 TANYA M. SANERIB (OSB No. 025526) [email protected] CHRISTOPHER WINTER (OSB No. 984355) [email protected] Crag Law Center 917 SW Oak Street, Suite 417 Portland, OR 97205 (503) 525.2722 (Sanerib) (503) 525.2725 (Winter) (503) 296.5454 (Fax) Lead Counsel JONATHAN OSTAR (OSB No. 03416) [email protected] Organizing People-Activating Leaders (OPAL) 2407 SE 49th Ave Portland OR 97206 (503) 407.9145 Attorneys for Plaintiffs IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF OREGON PORTLAND DIVISION HAYDEN ISLAND LIVABILITY Case No. 3: __________ PROJECT, HERMAN KACHOLD, DONNA MURPHY, HAYDEN ISLAND MANUFACTURED HOME COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY COMMUNITY HOMEOWNERS AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF ASSOCIATION, PAMELA FERGUSON, and ORGANIZING PEOPLE- (Violations of the National Environmental ACTIVATING LEADERS, Policy Act, Administrative Procedure Act and Clean Air Act consistency requirements) Plaintiffs, v. COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF - Page 1 of 39 Case 3:12-cv-01181 Document 1 Filed 07/02/12 Page 2 of 39 Page ID#: 2 PHILLIP DITZLER, in his official capacity as Federal Highway Administration Oregon Division Administrator, DANIEL M. MATHIS, in his capacity as Federal Highway Administration Washington Division Administrator; the FEDERAL HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION, an administrative agency of the United States Department of Transportation; RICHARD F. KROCHALIS, in his official capacity as Federal Transit Administration Regional Administrator of Region 10, and the FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION, an administrative agency of the United States Department of Transportation, Defendants. INTRODUCTION 1. This action filed pursuant to the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), 5 U.S.C. -

December 2019 Progress Report

Interstate Bridge Replacement Program December 2019 Progress Report December 2019 Progress Report i This page intentionally left blank. ii Interstate Bridge Replacement Program December 2, 2019 (Electronic Transmittal Only) The Honorable Governor Inslee The Honorable Kate Brown WA Senate Transportation Committee Oregon Transportation Commission WA House Transportation Committee OR Joint Committee on Transportation Dear Governors, Transportation Commission, and Transportation Committees: On behalf of the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) and the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), we are pleased to submit the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program status report, as directed by Washington’s 2019-21 transportation budget ESHB 1160, section 306 (24)(e)(iii). The intent of this report is to share activities that have lead up to the beginning of the biennium, accomplishments of the program since funding was made available, and future steps to be completed by the program as it moves forward with the clear support of both states. With the appropriation of $35 million in ESHB 1160 to open a project office and restart work to replace the Interstate Bridge, Governor Inslee and the Washington State Legislature acknowledged the need to renew efforts for replacement of this aging infrastructure. Governor Kate Brown and the Oregon Transportation Commission (OTC) directed ODOT to coordinate with WSDOT on the establishment of a project office. The OTC also allocated $9 million as the state’s initial contribution, and Oregon Legislative leadership appointed members to a Joint Committee on the Interstate Bridge. These actions demonstrate Oregon’s agreement that replacement of the Interstate 5 Bridge is vital. As is conveyed in this report, the program office is working to set this project up for success by working with key partners to build the foundation as we move forward toward project development.