Arxiv:1509.07761V2 [Cs.CL] 8 Dec 2015 Ocpsadies Uha Eerto,Wahr Eilsadbu Activities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transport and Map Symbols Range: 1F680–1F6FF

Transport and Map Symbols Range: 1F680–1F6FF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

Character Properties 4

The Unicode® Standard Version 14.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see https://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2021 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at https://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see https://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 14.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-29-0 (https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/) 1. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 4.1 This File Contains an Excerpt from the Character Code Tables and List of Character Names for the Unicode Standard, Version 4.1

Miscellaneous Symbols Range: 2600–26FF The Unicode Standard, Version 4.1 This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 4.1. Characters in this chart that are new for The Unicode Standard, Version 4.1 are shown in conjunction with any existing characters. For ease of reference, the new characters have been highlighted in the chart grid and in the names list. This file will not be updated with errata, or when additional characters are assigned to the Unicode Standard. See http://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See http://www.unicode.org/Public/4.1.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 4.1. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the on-line reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 4.1 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this excerpt file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 4.1, at http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode4.1.0/, including sections unchanged in The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 (ISBN 0-321-18578-1), as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, and #34, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available on-line. See http://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and http://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Miscellaneous Mathematical Symbols-A Range: 27C0–27EF

Miscellaneous Mathematical Symbols-A Range: 27C0–27EF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Musical Symbols Range: 1D100–1D1FF

Musical Symbols Range: 1D100–1D1FF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Unicode Characters in Proofpower Through Lualatex

Unicode Characters in ProofPower through Lualatex Roger Bishop Jones Abstract This document serves to establish what characters render like in utf8 ProofPower documents prepared using lualatex. Created 2019 http://www.rbjones.com/rbjpub/pp/doc/t055.pdf © Roger Bishop Jones; Licenced under Gnu LGPL Contents 1 Prelude 2 2 Changes 2 2.1 Recent Changes .......................................... 2 2.2 Changes Under Consideration ................................... 2 2.3 Issues ............................................... 2 3 Introduction 3 4 Mathematical operators and symbols in Unicode 3 5 Dedicated blocks 3 5.1 Mathematical Operators block .................................. 3 5.2 Supplemental Mathematical Operators block ........................... 4 5.3 Mathematical Alphanumeric Symbols block ........................... 4 5.4 Letterlike Symbols block ..................................... 6 5.5 Miscellaneous Mathematical Symbols-A block .......................... 7 5.6 Miscellaneous Mathematical Symbols-B block .......................... 7 5.7 Miscellaneous Technical block .................................. 7 5.8 Geometric Shapes block ...................................... 8 5.9 Miscellaneous Symbols and Arrows block ............................. 9 5.10 Arrows block ........................................... 9 5.11 Supplemental Arrows-A block .................................. 10 5.12 Supplemental Arrows-B block ................................... 10 5.13 Combining Diacritical Marks for Symbols block ......................... 11 5.14 -

The Unicode Standard 5.2 Code Charts

Miscellaneous Symbols Range: 2600–26FF The Unicode Standard, Version 5.2 This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 5.2. Characters in this chart that are new for The Unicode Standard, Version 5.2 are shown in conjunction with any existing characters. For ease of reference, the new characters have been highlighted in the chart grid and in the names list. This file will not be updated with errata, or when additional characters are assigned to the Unicode Standard. See http://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See http://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-5.2/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 5.2. See http://www.unicode.org/Public/5.2.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 5.2. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 5.2 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 5.2, online at http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode5.2.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, and #44, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. -

Emoji Art: the Aesthetics of

Emoji art: The aesthetics of P.D. Magnus January 2018 This is an unpublished draft. Comments are welcome. e-mail: pmagnus(at)fecundity.com web: http://www.fecundity.com/job Abstract This paper explores the possibility of art made using emoji (picture characters like the pile-of-poo glyph in the title). That such art is possible is apprarent from some specific examples. Although these cases are of- ten described in terms of “translation” between emoji and English, emoji cannot generally be given a literal natural-language translation. So what kind of thing is an emoji work? A particular emoji work could turn out to be (1) a digital image, like an illustration; (2) a specified string of emoji characters, in the way that a natural-language novel is a specified string of letters; or (3) a single-instance work, a particular display. keywords: emoji, emoji art, Emoji Dick, emoji poems, art ontology Emoji are picture characters familiar from smart phone text messages. Given their ubiquity, it is inevitable that emoji have been used in works of art. What kind of art are they, though? I begin in §1 by discussing the history of emoji. One of the more notable emoji is the pile of poo which figures in the title of this paper. In§2, I consider the meaning of emoji and argue that there is not generally a natural-language translation for emoji. In §§3–4, I discuss some specific works of emoji art: Fred Benenson’s Emoji Dick and Carina Finn and Stephanie Berger’s emoji poems. -

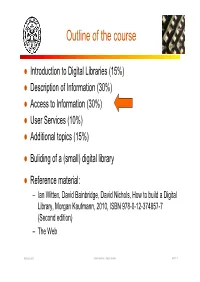

Outline of the Course

Outline of the course Introduction to Digital Libraries (15%) Description of Information (30%) Access to Information (()30%) User Services (10%) Additional topics (()15%) Buliding of a (small) digital library Reference material: – Ian Witten, David Bainbridge, David Nichols, How to build a Digital Library, Morgan Kaufmann, 2010, ISBN 978-0-12-374857-7 (Second edition) – The Web FUB 2012-2013 Vittore Casarosa – Digital Libraries Part 7 -1 Access to information Representation of characters within a computer Representation of documents within a computer – Text documents – Images – Audio – Video How to store efficiently large amounts of data – Compression How to retrieve efficiently the desired item(s) out of large amounts of data – Indexing – Query execution FUB 2012-2013 Vittore Casarosa – Digital Libraries Part 7 -2 Representation of characters The “natural” wayyp to represent ( (palphanumeric ) characters (and symbols) within a computer is to associate a character with a number,,g defining a “coding table” How many bits are needed to represent the Latin alphabet ? FUB 2012-2013 Vittore Casarosa – Digital Libraries Part 7 -3 The ASCII characters The 95 printable ASCII characters, numbdbered from 32 to 126 (dec ima l) 33 control characters FUB 2012-2013 Vittore Casarosa – Digital Libraries Part 7 -4 ASCII table (7 bits) FUB 2012-2013 Vittore Casarosa – Digital Libraries Part 7 -5 ASCII 7-bits character set FUB 2012-2013 Vittore Casarosa – Digital Libraries Part 7 -6 Representation standards ASCII (late fifties) – AiAmerican -

SSAC Advisory on the Use of Emoji in Domain Names SAC095 SSAC Advisory on the Use of Emoji in Domain Names

SSAC Advisory on the Use of Emoji in Domain Names SAC095 SSAC Advisory on the Use of Emoji in Domain Names An Advisory from the ICANN Security and Stability Advisory Committee (SSAC) 25 May 2017 SAC095 1 SSAC Advisory on the Use of Emoji in Domain Names Preface This is an advisory to the ICANN Board, the ICANN community, and, more broadly, the Internet community from the ICANN Security and Stability Advisory Committee (SSAC) on the use of emoji in domain names. The SSAC focuses on matters relating to the security and integrity of the Internet’s naming and address allocation systems. This includes operational matters (e.g., pertaining to the correct and reliable operation of the root zone publication system), administrative matters (e.g., pertaining to address allocation and Internet number assignment), and registration matters (e.g., pertaining to registry and registrar services). SSAC engages in ongoing threat assessment and risk analysis of the Internet naming and address allocation services to assess where the principal threats to stability and security lie, and advises the ICANN community accordingly. The SSAC has no authority to regulate, enforce, or adjudicate. Those functions belong to other parties, and the advice offered here should be evaluated on its merits. SAC095 2 SSAC Advisory on the Use of Emoji in Domain Names Table of Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................... 4 2 Emoji in Domain Names .............................................................................. -

Supplement Notes on Alphanumeric Representation Device, but Is Often Either 8 Or 10

Supplement Notes on Alphanumeric Representation device, but is often either 8 or 10. LF (NL line feed, new line) - Moves the cursor (or print head) to a SUB (substitute) new line. On Unix systems, moves to a new line 2.1 Introduction AND all the way to the left. VT (vertical tab) ESC (escape) Inside a computer program or data file, text is stored as a sequence of numbers, just like everything else. These sequences are FF (form feed) - Advances paper to the top of the next page (if the FS (file separator) integers of various sizes, values, and interpretations, and it is the code pages, character sets, and encodings that determine how output device is a printer). integer values are interpreted. CR (carriage return) - Moves the cursor all the way to the left, but GS (group separator) does not advance to the next line. Text consists of characters, mostly. Fancy text or rich text includes display properties like color, italics, and superscript styles, SO (shift out) - Switches output device to alternate character set. RS (record separator) but it is still based on characters forming plain text. Sometimes the distinction between fancy text and plain text is complex, SI (shift in) - Switches output device back to default character set. US (unit separator) and the distinction may depend on the application. Here, we focus on plain text. 2. 001x xxxx Numeric and “specials” or punctuation. So, what is a character? Typically, it is a letter. Also, it is a digit, a period, a hyphen, punctuation, and mathematic symbol. 3. 010x xxxx Upper case letters (and some punctuation) There are also control characters (typically not visible) that define the end of a line or paragraph.