Proposal for Alchemical Symbols in Unicode

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Script Symbology Sequence, Duality & Correspondence in Screenplays & Drama

Script Symbology Sequence, Duality & Correspondence in Screenplays & Drama John Fraim John Fraim 189 Keswick Drive New Albany, OH 43054 760-844-2595 [email protected] www.midnightoilstudios.org www.symbolism.org www.desertscreenwritersgroup.com www.greathousestories.com © 2017 – John Fraim FRAIM / SS 1 “Eternal truth needs a human language that varies with the spirit of the times. The primordial images undergo ceaseless transformation and yet remain ever the same, but only in a new form can they be understood anew. Always they require a new interpretation if, as each formulation becomes obsolete, they are not to lose their spellbinding power.” Carl Jung The Psychology of Transference The endless cycle of idea and action, Endless invention, endless experiment, Brings knowledge of motion, but not of stillness; Knowledge of speech, but not of silence; Knowledge of words, and ignorance of the Word. T.S. Eliot The Rock “The essential problem is to know what is revealed to us not by any particular version of a symbol, but by the whole of symbolism.” Mercea Eliade The Rites and Symbols of Initiation “Francis Bacon never tired of contrasting hot and cool prose. Writing in ‘methods’ or complete packages, he contrasted with writing in aphorisms, or single observations such as ‘Revenge is a kind of wild justice. The passive consumer wants packages, but those, he suggested, who are concerned in pursuing knowledge and in seeking causes will resort to aphorisms, just because they are incomplete and require participation in depth.” Marshall McLuhan Understanding Media FRAIM / SS 2 To Eric McLuhan Relentless provocateur over the years FRAIM / SS 3 Contents Preface 8 Introduction 10 I. -

Transport and Map Symbols Range: 1F680–1F6FF

Transport and Map Symbols Range: 1F680–1F6FF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

AN ABSTRACT of the THESIS of Cindy Blakeley for the Master of Arts

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Cindy Blakeley for the Master of Arts (name of student) (degree) in English presented on May 12, 1993 (major) (date) Title: John Donne's Alchemical Vision ~.~ Abstract Approved. From the earliest of times, many have pursued the goals of alchemy, a torm ot chemistry and speculative philosophy in which advocates attempted to discover an elixir ot lite and a method for converting base metals into gold. To the true alchemist, the "Great Work" was more than a science or a philosophy--it was a religion. The seventeenth-century poet, John Donne, though not a practicing alchemist, was himself interested in alchemy's religious connotations. In his poetry, he indicates his concern with man's spiritual transcendence which parallels the extraction of pure spiritual essences from any form ot base matter. In addition, the presumed sequence in which he writes his poems (precise dates of composition are, as yet, not established) reveals his growing fascination with the spiritual message suggested by alchemy. In "Loves Alchymie," likely written before Donne's marriage to Ann More, Donne is pessimistically questioning man's ability to transcend his base physical nature and, therefore, doubts the validity of spiritual alchemy. Then, during his love affair with and marriage to Ann More, he feels his new experiences with love and recently acquired understanding of love prove man is capable of obtaining spiritual purity. At this time, he writes "The Extasie," "The Good-Morrow," and "A Valediction Forbidding Mourning," employing basic alchemical imagery to support his notion that a union of body, soul, and spirit between man and woman is possible. -

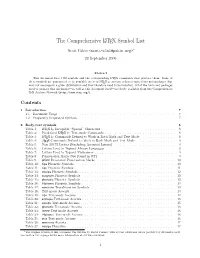

The Comprehensive LATEX Symbol List

The Comprehensive LATEX Symbol List Scott Pakin <[email protected]>∗ 22 September 2005 Abstract This document lists 3300 symbols and the corresponding LATEX commands that produce them. Some of these symbols are guaranteed to be available in every LATEX 2ε system; others require fonts and packages that may not accompany a given distribution and that therefore need to be installed. All of the fonts and packages used to prepare this document—as well as this document itself—are freely available from the Comprehensive TEX Archive Network (http://www.ctan.org/). Contents 1 Introduction 7 1.1 Document Usage . 7 1.2 Frequently Requested Symbols . 7 2 Body-text symbols 8 Table 1: LATEX 2ε Escapable “Special” Characters . 8 Table 2: Predefined LATEX 2ε Text-mode Commands . 8 Table 3: LATEX 2ε Commands Defined to Work in Both Math and Text Mode . 8 Table 4: AMS Commands Defined to Work in Both Math and Text Mode . 9 Table 5: Non-ASCII Letters (Excluding Accented Letters) . 9 Table 6: Letters Used to Typeset African Languages . 9 Table 7: Letters Used to Typeset Vietnamese . 9 Table 8: Punctuation Marks Not Found in OT1 . 9 Table 9: pifont Decorative Punctuation Marks . 10 Table 10: tipa Phonetic Symbols . 10 Table 11: tipx Phonetic Symbols . 11 Table 13: wsuipa Phonetic Symbols . 12 Table 14: wasysym Phonetic Symbols . 12 Table 15: phonetic Phonetic Symbols . 12 Table 16: t4phonet Phonetic Symbols . 13 Table 17: semtrans Transliteration Symbols . 13 Table 18: Text-mode Accents . 13 Table 19: tipa Text-mode Accents . 14 Table 20: extraipa Text-mode Accents . -

Lapis Philosophorum")

Alchemical Symbols on Stećak Tombstones and their Meaning ("Lapis Philosophorum") Amer Dardağan, MA Go directly to the text of the paper Abstract Stećak is the official name for approximately 70,000 mysterious medieval tombstones scattered across Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the border areas of Croatia, Montenegro, and Serbia. To understand the meaning of the many symbols of alchemy and theurgy on the stećak tombstones, a researcher of medieval religions must relate to a world in which spirituality and Hermetic philosophy play a central role. In order to grasp the phenomenology of stećci (plural of stećak) in their total complexity, the symbols should be interpreted through philosophy (Neoplatonism), theology (Cataphatic and Apophatic theology), and the practices of alchemy and theurgy. For example, one recurring motif is the appearance of an unexpected third component in alchemical work. The alchemical imagination constantly reminds us that opposing forces in nature have to unite to form a special relationship, which through their unification, the “mysterious third” (Alchemical "Egg," "Philosopher's Stone," "Tree of Life") occurs that transcends ordinary existence. Without this kind of basic knowledge of the principles and philosophy of Neoplatonism and Hermeticism, it is very difficult to understand the symbols found on the tombstones. In the past, most Medieval scholars believed the stečak symbols were only decorative motifs and completely overlooked the deeper philosophical and spiritual content that was part of the Bosnian religious tradition at that time. The main goal of this paper is to provide readers with deeper insights on stećci as one of the most mysterious phenomena of Medieval Europe, and to reveal their spiritual and intellectual relationship with the practice of alchemy through interpretation of inscribed symbols on these tombstones and their connection with Neoplatonic and Hermetic philosophy. -

Alchemy Rediscovered and Restored

ALCHEMY REDISCOVERED AND RESTORED BY ARCHIBALD COCKREN WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE EXTRACTION OF THE SEED OF METALS AND THE PREPARATION OF THE MEDICINAL ELIXIR ACCORDING TO THE PRACTICE OF THE HERMETIC ART AND OF THE ALKAHEST OF THE PHILOSOPHER TO MRS. MEYER SASSOON PHILADELPHIA, DAVID MCKAY ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN 1941 Alchemy Rediscovered And Restored By Archibald Cockren. This web edition created and published by Global Grey 2013. GLOBAL GREY NOTHING BUT E-BOOKS TABLE OF CONTENTS THE SMARAGDINE TABLES OF HERMES TRISMEGISTUS FOREWORD PART I. HISTORICAL CHAPTER I. BEGINNINGS OF ALCHEMY CHAPTER II. EARLY EUROPEAN ALCHEMISTS CHAPTER III. THE STORY OF NICHOLAS FLAMEL CHAPTER IV. BASIL VALENTINE CHAPTER V. PARACELSUS CHAPTER VI. ALCHEMY IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES CHAPTER VII. ENGLISH ALCHEMISTS CHAPTER VIII. THE COMTE DE ST. GERMAIN PART II. THEORETICAL CHAPTER I. THE SEED OF METALS CHAPTER II. THE SPIRIT OF MERCURY CHAPTER III. THE QUINTESSENCE (I) THE QUINTESSENCE. (II) CHAPTER IV. THE QUINTESSENCE IN DAILY LIFE PART III CHAPTER I. THE MEDICINE FROM METALS CHAPTER II. PRACTICAL CONCLUSION 'AUREUS,' OR THE GOLDEN TRACTATE SECTION I SECTION II SECTION III SECTION IV SECTION V SECTION VI SECTION VII THE BOOK OF THE REVELATION OF HERMES 1 Alchemy Rediscovered And Restored By Archibald Cockren THE SMARAGDINE TABLES OF HERMES TRISMEGISTUS said to be found in the Valley of Ebron, after the Flood. 1. I speak not fiction, but what is certain and most true. 2. What is below is like that which is above, and what is above is like that which is below for performing the miracle of one thing. -

Alpha Chi Sigma Fraternity Sourcebook, 2013-2014 This Sourcebook Is the Property Of

Alpha Chi Sigma Sourcebook A Repository of Fraternity Knowledge for Reference and Education Academic Year 2013-2014 Edition 1 l Alpha Chi Sigma Fraternity Sourcebook, 2013-2014 This Sourcebook is the property of: ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Full Name Chapter Name ___________________________________________________ Pledge Class ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Date of Pledge Ceremony Date of Initiation ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Master Alchemist Vice Master Alchemist ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Master of Ceremonies Reporter ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Recorder Treasurer ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Alumni Secretary Other Officer Members of My Pledge Class ©2013 Alpha Chi Sigma Fraternity 6296 Rucker Road, Suite B | Indianapolis, IN 46220 | (800) ALCHEMY | [email protected] | www.alphachisigma.org Click on the blue underlined terms to link to supplemental content. A printed version of the Sourcebook is available from the National Office. This document may be copied and distributed freely for not-for-profit purposes, in print or electronically, provided it is not edited or altered in any -

Iconographic Architecture As Signs and Symbols in Dubai

ICONOGRAPHIC ARCHITECTURE AS SIGNS AND SYMBOLS IN DUBAI HARPREET SETH Ph.D. UNIVERSITY OF WOLVERHAMPTON 2013 i ICONOGRAPHIC ARCHITECTURE AS SIGNS AND SYMBOLS IN DUBAI By Harpreet Seth B.Arch., M.Arch. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University of Wolverhmapton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Technology (STECH) Department of Architecture and Design University of Wolverhampton February 2013 This work or any part thereof has not previously been presented in any form to the University or to any other body whether for the purpose of assessment, publication or for any other purpose (unless otherwise indicated). Save for any express acknowledgements, references and/or bibliographies cited in the work, I confirm that the intellectual content of the work is the result of my own efforts and no other person. The right of Harpreet Seth to be identified as the author of this work is asserted in accordance with ss.77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. At this date copyright is owned by the author. Signature (Harpreet Seth) Date 16 / 03/ 2013 Mrs. Harpreet Seth (M.Arch.) Iconic Architecture in Dubai as Signs and Symbols February 2013 ii Abstract This study seeks to investigate the impact of architectural icons on the cities that they are built in, especially those in Dubai to understand the perceptions and associations of ordinary people with these icons, thus analysing their impact on the quality of life in the city. This is an important study with the advent of ‘iconism’ in architecture that has a growing acceptance and demand, wherein the status of a piece of architecture is predetermined as an icon by the media and not necessarily by the people. -

Alchemylab Articles\374

Alchemical Theory The One Thing (or the Subtle Ether) Space, whether interplanetary, inner matter, or inter-organic, is filled with a subtle presence emanating from the One Thing of the universe. Later alchemists called it, as did the ancients, the subtle Ether. This primordial fluid or fabric of space pervades everything and all matter. Metal, mineral, tree, plant, animal, man; each is charged with the Ether in varying degrees. All life on the planet is charged in like manner; a world is built up in this fluid and move through a sea of it. Alchemical Ether, which some Hermeticists call the Astral Light, determines the constitution of bodies. Hardness and softness, solidity and liquidity, all depend on the relative proportion of ethereal and ponderable matter of which they me composed. The arbitrary division and classification of physical science, the whole range of physical phenomena, proceeds from the primary Ether, for science has reduced matter as we know it to nothing but Ether, which, although not solid matter, is still matter, the First Matter of the alchemists. When most of us speak of matter, of course, we usually visualize solid substance, but it has been proved by that matter is not actually solid, but merely a stress, a strain in the etheric field of time and space. The atom and the electrons and protons of which it is composed, all move in a sea of Ether, so, that in accordance with this theory of alchemy, the very air we breathe, the very bodies we inhabit, all things most likewise be moving in this sea of Ether, the parent element from which all manifestation has come. -

The Zodiac and the Salts of Salvation. Part One, by Dr. George

? sI I X5ha 2o6iac atx6 tl)e Salts of Salvation PART ONE by : ; . Dr. George Washington Garey the relation of the mineral salts- op the: boi?t; to the signs of the zodiac (Fourteenth and Memorial Edition) , PART TWO AN ESOTERIC ANALYSIS AND SYNTHESIS OF THE ZODIACAL SIGNS AND THEIR PHYSIO- CHEMICAL ALLOCATIONS BY INEZ EUDORA PERRY i First Edition PUBLISHED BY The i Carey-Perry Chemistry School of the of Life j Hollywood, Los Angeles, California N I >- u IT < O (5 0 K o {Mi* UJ o Mg>. K Q o 0 I- i-i < o as z u < u K u <!a (fl ft Offl N D Q I- Z U ~ < Ui n Eu I *cj 0 Io c t- 3 B < 0 6 IE o ° E < i 3 5 ■ o < ; u Aft Copyright BY INEZ EUDORA PERRY Hollywood, California, U. S. A. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Including Translation into Other Languages AND Publication in All Foreign Countries Printed by J. F. ROWNY PRESS SANTA BARBARA, CAL. CONTENTS Part One Introduction v Poem, "The Saint George" of Biochemistry . ix In Memoriam xii Poem, "The New Name" xix Biochemistry 21 Esoteric Chemistry 22 The Ultimate of Biochemistry 23 The Twelve Cell-Salts of the Zodiac Aries, the Lamb of God 25 Taurus, the Winged Bull of the Zodiac .... 27 The Chemistry of Gemini 28 Cancer: the Chemistry of the Crab 29 Leo : the Heart of the Zodiac 31 Virgo : the Virgin Mary 32 Libra : the Loins 34 Influence of the Sun on Vibration of Blood at Birth : Scorpio 35 The Chemistry of Sagittarius 37 Capricorn : the Goat of the Zodiac 38 The Sign of the Son of Man : Aquarius 41 Pisces: the Fish that Swim in the Pure Sea .. -

Secret Book (Liber Secretus), by Artephius

INDEX Alchemical Manuscript Series Volume One: Triumphal Chariot of Antimony, by Basil Valentine Triumphal Chariot of Antimony by Basil Valentine is considered to be a masterpiece of chemical literature. The treatise provides important advances in the manufacture and medical action of chemical preparations, such as, metallic antimony, solutions of caustic alkali, the acetates of lead and copper, gold fulminate and other salts. Accounts of practical laboratory operations are clearly presented. Instructions in this book are noteworthy, as they provide weights and proportions, a rarity in alchemical literature. Volume Two: Golden Chain of Homer, by Anton Kirchweger, Part 1 Frater Albertus was once asked if he could only have one book on alchemy, which would it be? He answered that it would be the Golden Chain of Homer. This collection of books written by several authors and printed in various editions, was first printed in 1723. Concepts of Platonic, Mosaic, and Pythagorean philosophy provide extensive instruction in Cosmic, Cabbalistic, and laboratory Alchemical Philosophy. Volume Three: Golden Chain of Homer, by Anton Kirchweger, Part 2 Frater Albertus was once asked if he could only have one book on alchemy, which would it be? He answered that it would be the Golden Chain of Homer. This collection of books written by several authors and printed in various editions, was first printed in 1723. Concepts of Platonic, Mosaic, and Pythagorean philosophy provide extensive instruction in Cosmic, Cabbalistic, and laboratory Alchemical Philosophy. Volume Four: Complete Alchemical Writings, by Isaac Hollandus, Part 1 Complete Alchemical Writings was written by father and son Dutch adepts, both named Isaac Hollandus.