Iconographic Architecture As Signs and Symbols in Dubai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Script Symbology Sequence, Duality & Correspondence in Screenplays & Drama

Script Symbology Sequence, Duality & Correspondence in Screenplays & Drama John Fraim John Fraim 189 Keswick Drive New Albany, OH 43054 760-844-2595 [email protected] www.midnightoilstudios.org www.symbolism.org www.desertscreenwritersgroup.com www.greathousestories.com © 2017 – John Fraim FRAIM / SS 1 “Eternal truth needs a human language that varies with the spirit of the times. The primordial images undergo ceaseless transformation and yet remain ever the same, but only in a new form can they be understood anew. Always they require a new interpretation if, as each formulation becomes obsolete, they are not to lose their spellbinding power.” Carl Jung The Psychology of Transference The endless cycle of idea and action, Endless invention, endless experiment, Brings knowledge of motion, but not of stillness; Knowledge of speech, but not of silence; Knowledge of words, and ignorance of the Word. T.S. Eliot The Rock “The essential problem is to know what is revealed to us not by any particular version of a symbol, but by the whole of symbolism.” Mercea Eliade The Rites and Symbols of Initiation “Francis Bacon never tired of contrasting hot and cool prose. Writing in ‘methods’ or complete packages, he contrasted with writing in aphorisms, or single observations such as ‘Revenge is a kind of wild justice. The passive consumer wants packages, but those, he suggested, who are concerned in pursuing knowledge and in seeking causes will resort to aphorisms, just because they are incomplete and require participation in depth.” Marshall McLuhan Understanding Media FRAIM / SS 2 To Eric McLuhan Relentless provocateur over the years FRAIM / SS 3 Contents Preface 8 Introduction 10 I. -

Global Financial Crisis and Its Effects on the Crisis in Dubai

British Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 71 February 2012, Vol. 4 (1) Global Financial Crisis and its Effects on the Crisis in Dubai *Dr. Fares Jamil Alsufy Department of Accountancy Al isra University, 22 Jordan – Amman 11622 **Dr. Mae'n A.R Juwaihan Law Department Al isra University, 22 Jordan - Amman 11622 *** Dr. Awad Ako irshedah Law Department Al isra University, 22 Jordan - Amman 11622 Introduction: - With the progress of science and technology development and information in the presence of the Web is the world together where he became an economic bloc interrelated and complex, affecting any economic event in a particular area on a number of regions and economic centers in the world the sense of the interdependence of interests of businessmen in Britain and the United States of America with a group the huge investments in the region such as Dubai may affect any economic event in one of the countries mentioned have a direct and tangible in the other country, whether the event recovery or recession, the birth of companies and major facilities or the collapse of another, so that the influence on the other directly, but no one guess the kind of impact a positive or negative. Problem of the study: - The problem of the study in the misuse and interpretation of financial statements and the lack of credibility of the information given by the departments of large companies and this in itself is a weakness in the global management system that puts the region in a serious financial situation. In addition, the weakening of the policy of lending and lack of caution by banks and private real estate which is enough and the absence of objectivity in the process of assessing the mortgaged properties, which have been inflating their values in an exaggerated manner, causing it to drain liquidity from the banks and the inability of borrowers to repay and which led turn to the collapse of the plight of banking sector_ economy column in any country_. -

Urban Megaprojects-Based Approach in Urban Planning: from Isolated Objects to Shaping the City the Case of Dubai

Université de Liège Faculty of Applied Sciences Urban Megaprojects-based Approach in Urban Planning: From Isolated Objects to Shaping the City The Case of Dubai PHD Thesis Dissertation Presented by Oula AOUN Submission Date: March 2016 Thesis Director: Jacques TELLER, Professor, Université de Liège Jury: Mario COOLS, Professor, Université de Liège Bernard DECLEVE, Professor, Université Catholique de Louvain Robert SALIBA, Professor, American University of Beirut Eric VERDEIL, Researcher, Université Paris-Est CNRS Kevin WARD, Professor, University of Manchester ii To Henry iii iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My acknowledgments go first to Professor Jacques Teller, for his support and guidance. I was very lucky during these years to have you as a thesis director. Your assistance was very enlightening and is greatly appreciated. Thank you for your daily comments and help, and most of all thank you for your friendship, and your support to my little family. I would like also to thank the members of my thesis committee, Dr Eric Verdeil and Professor Bernard Declève, for guiding me during these last four years. Thank you for taking so much interest in my research work, for your encouragement and valuable comments, and thank you as well for all the travel you undertook for those committee meetings. This research owes a lot to Université de Liège, and the Non-Fria grant that I was very lucky to have. Without this funding, this research work, and my trips to UAE, would not have been possible. My acknowledgments go also to Université de Liège for funding several travels giving me the chance to participate in many international seminars and conferences. -

Apophenia: the Postmodern Trap in Auster's Fictions

Master’s Degree programme – Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004) in European, American and Postcolonial Language and Literature Final Thesis Apophenia: The Postmodern Trap in Auster’s Fictions Supervisor Prof.sa Pia Masiero Co-supervisor Prof.sa Francesca Bisutti Graduand Luca Barban Matriculation Number 847317 Academic Year 2015 / 2016 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 1. The mechanics of postmodern reality 1.1 Chance and necessity ..................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 A brief history of chance ............................................................................................................................... 7 1.3 Chance in postmodernism ......................................................................................................................... 11 1.4 Paul Auster and the centrality of chance ............................................................................................ 14 2. Order in Chaos 2.1. Seriality and Synchronicity .................................................................................................................... 24 2.2. Apophenia ...................................................................................................................................................... 27 2.3. Order in chaos ............................................................................................................................................. -

New Investment:Layout 1 30/7/09 08:56 Page 1

new investment:Layout 1 30/7/09 08:56 Page 1 Altair Development in Lusail, Doha, Qatar. new investment:Layout 1 30/7/09 08:56 Page 3 Contacts Contents All communications and enquiries relating Executive Summary 01 to this offer should be directed to either: The Developers and Partners 02 Qatar Overview 03 Equity Investment Enquiries Investment & Infrastructure 07 Will Hean Property Market 09 Kenmore Property Group Lusail Overview 14 PO Box 282110 The Altair Development 17 Dubai UAE Tel: +971 (0) 42942032 Appendices [email protected] Key Executives 23 Developers and Sales Agents 27 Property Residential Enquiries Track Records 29 Andy McEwan Select Property Group Limited The Box Brooke Court Lower Meadow Road Wilmslow Cheshire United Kingdom SK9 3ND Tel: +44 (0) 7765237600 [email protected] Investment brochure for The Altair Development, Lusail, Doha. Investment brochure for The Altair Development, Lusail, Doha. new investment:Layout 1 30/7/09 08:56 Page 5 02 Executive summary The Developers and Partners Tameer Real Estate Company WLL has acquired a 72,000 square foot plot in the Tameer Real Estate Company WLL was established in Qatar in its current form waterfront residential area of the Lusail masterplan, an expansion area just to in 2006 with a paid up capital of 324 million Qatari Riyals and assets over 1Billion the north of the centre of Doha, the capital of the State of Qatar. The plot QAR. Tameer is a national and international real estate development, investment surrounds a private beach at the northern end of the waterfront district. Lusail and holding company. -

Prospects for the Dubai Real Estate and Hospitality Sectors July 2020

Post-pandemic plans for concrete recovery Prospects for the Dubai real estate and hospitality sectors July 2020 FOREWORD The Covid-19 pandemic is proving Based on KPMG’s experience in the real estate and hospitality sectors, and conversations with an enormous challenge for our stakeholders, we have analyzed the current societies and healthcare systems; the situation. As a product of our research, this consequences for the global document seeks to offer insight into the challenges faced within the residential, office and local economies are both and mall segments of the real estate market, unprecedented and unpredictable. as well as the hospitality industry. Many economists are convinced we are heading We would like to thank those who provided for a significant economic downturn and remain invaluable insight, while rising to the challenges unsure as to how long a recovery will take. we are all currently experiencing. However, responses from governments and regulatory bodies have been prompt. In the Please feel free to contact us with UAE, at the federal and emirate levels, a variety any comments or queries. of measures have been taken to support the economy and its citizens. Sidharth Mehta Partner Head of Building, Construction and Real Estate KPMG Lower Gulf Limited E [email protected] CONTENTS Residential Page 06 Office space Page 09 Hospitality sector Conclusions Executive summary Regional outlook Real estate sector Page 14 Page 01 Page 02 Page 05 Page 18 Shopping malls Page 11 About KPMG Page 20 Real estate and hospitality services Page 20 References Page 21 — A significant reduction in personal and — How deeply the sector is affected will largely business travel is impacting the sector with depend on travel restrictions and traveler HIGHER occupancy and revenue per available room sentiment. -

Implementing Sustainable Construction Practices in Dubai – a Policy Instrument Assessment

Master Thesis in Built Environment (15 credits) Implementing Sustainable Construction Practices in Dubai – a policy instrument assessment Marco Maguina Academic Supervisor: Catarina Thormark Spring Semester 2011 Master Thesis in Built Environment Implementing Sustainable Construction Practices in Dubai – a policy instrument assessment Author: Marco Maguina Faculty: Culture and Society School: Malmö University Master Thesis: 15 credits Academic Supervisor: Catarina Thormark Examiner: Johnny Kronvall Maguina, Marco 2 Master Thesis in Built Environment SUMMARY Recognized as one of the main obstacles to sustainable development, climate change is caused and accelerated by the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions generated from all energy end-user sectors. The building sector alone consumes around 40% of all produced energy worldwide. Reducing this sector’s energy consumption has therefore come into focus as one of the key issues to address in order to meet the climate change challenge. Implementing sustainable construction practices, such as LEED, can significantly reduce the building’s energy and water consumption. Prescribing these practices may however encounter several barriers that can produce other than intended results. Since the beginning of 2008 Dubai mandates a LEED certification for the better part of all new constructions developed within the emirate, nevertheless the success of this regulation is debatable. This thesis identifies the barriers the introduction of the sustainable construction practices in Dubai faced and analyses the reasons why the regulatory and voluntary policy instruments were not effective in dealing with these barriers. Understanding these barriers as well as the merits and weaknesses of the policy instruments will help future attempts to introduce sustainable construction practices. To put the research into context a literature review of relevant printed and internet sources has been performed. -

Dubai Real Estate Sector

Sector Monitor Series Dubai Real Estate Sector Dr. Eisa Abdelgalil Bader Aldeen Bakheet Data Management and Business Research Department 2007 Published by: DCCI – Data Management & Business Research Department P.O. Box 1457 Tel: + 971 4 2028410 Fax: + 971 4 2028478 Email: dm&[email protected] Website: www.dcci.ae Dubai, United Arab Emirates All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval or computer system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, taping or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN ………………………… i Table of Contents Table of Contents...........................................................................................................ii iii ....................................................................................................................ﻣﻠﺨﺺ ﺗﻨﻔﻴﺬي Executive Summary......................................................................................................vi 1. Introduction................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background..........................................................................................................1 1.2 Objective..............................................................................................................1 1.3 Research questions...............................................................................................1 1.4 Methodology and data..........................................................................................2 -

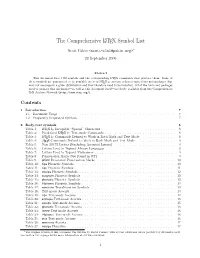

The Comprehensive LATEX Symbol List

The Comprehensive LATEX Symbol List Scott Pakin <[email protected]>∗ 22 September 2005 Abstract This document lists 3300 symbols and the corresponding LATEX commands that produce them. Some of these symbols are guaranteed to be available in every LATEX 2ε system; others require fonts and packages that may not accompany a given distribution and that therefore need to be installed. All of the fonts and packages used to prepare this document—as well as this document itself—are freely available from the Comprehensive TEX Archive Network (http://www.ctan.org/). Contents 1 Introduction 7 1.1 Document Usage . 7 1.2 Frequently Requested Symbols . 7 2 Body-text symbols 8 Table 1: LATEX 2ε Escapable “Special” Characters . 8 Table 2: Predefined LATEX 2ε Text-mode Commands . 8 Table 3: LATEX 2ε Commands Defined to Work in Both Math and Text Mode . 8 Table 4: AMS Commands Defined to Work in Both Math and Text Mode . 9 Table 5: Non-ASCII Letters (Excluding Accented Letters) . 9 Table 6: Letters Used to Typeset African Languages . 9 Table 7: Letters Used to Typeset Vietnamese . 9 Table 8: Punctuation Marks Not Found in OT1 . 9 Table 9: pifont Decorative Punctuation Marks . 10 Table 10: tipa Phonetic Symbols . 10 Table 11: tipx Phonetic Symbols . 11 Table 13: wsuipa Phonetic Symbols . 12 Table 14: wasysym Phonetic Symbols . 12 Table 15: phonetic Phonetic Symbols . 12 Table 16: t4phonet Phonetic Symbols . 13 Table 17: semtrans Transliteration Symbols . 13 Table 18: Text-mode Accents . 13 Table 19: tipa Text-mode Accents . 14 Table 20: extraipa Text-mode Accents . -

Martin Amis on Vladimir Nabokov's Work | Books | the Guardian

Martin Amis on Vladimir Nabokov's work | Books | The Guardian http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2009/nov/14/vladimir-naboko... The problem with Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov's unfinished novella, The Original of Laura, is being published despite the author's instructions that it be destroyed after his death. Martin Amis confronts the tortuous questions posed by a genius in decline Martin Amis The Guardian, Saturday 14 November 2009 larger | smaller Vladimir Nabokov in Switzerland, in about 1975. Photograph: Horst Tappe/Getty Images Language leads a double life – and so does the novelist. You chat with family and friends, you attend to your correspondence, you consult menus and shopping lists, you observe road signs (LOOK LEFT), and so on. Then you enter your study, where language exists in quite another form – as the stuff of patterned artifice. Most writers, I think, would want to go along with Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977), when he reminisced in 1974: The Original of Laura: (Dying is Fun) a Novel in Fragments (Penguin Modern Classics) by Vladimir Nabokov 304pp, Penguin Classics, £25 1 of 11 11/15/09 12:59 AM Martin Amis on Vladimir Nabokov's work | Books | The Guardian http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2009/nov/14/vladimir-naboko... Buy The Original of Laura: (Dying is Fun) a Novel in Fragments (Penguin Modern Classics) at the Guardian bookshop ". I regarded Paris, with its gray-toned days and charcoal nights, merely as the chance setting for the most authentic and faithful joys of my life: the coloured phrase in my mind under the drizzle, the white page under the desk lamp awaiting me in my humble home." Well, the creative joy is authentic; and yet it isn't faithful (in common with pretty well the entire cast of Nabokov's fictional women, creative joy, in the end, is sadistically fickle). -

The World Economy Today

THE WORLD ECONOMY TODAY: Major Trends and Developments First Edition 1 2 THE WORLD ECONOMY TODAY: Major Trends and Developments First Edition Joint publication, comprised of selected works of renowned scholars and experts representing: University of Antwerp, Belgium Bond University, Australia Center for Education, Policy Research and Economic Analysis ALTERNATIVE, Armenia Delft University of Technology, Netherlands Zhejiang Gongshang University, China International Monetary Fund, HQ in Washington D.C., USA University of San Francisco, USA Shinawatra International University, Thailand United Nations University, Belgium Yerevan State University, Armenia 3 Liliane Van Hoof, Ph.D., Professor of International Business Evrard Claessens, Professor of Economics L. Cuyvers, Professor of International Economics, Stijn Verherstraeten, Research Assistant Céline Storme, Industry Management Consulting Liesbeth Van de Wiele, Consultant Philippe Van Bets, MBA at University of Antwerp Michel Dumont, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Economics of Innovation at Delft University of Technology P. De Lombaerde, Associate Director at United Nations University Rosita Dellios, PhD, Associate Professor of International Relations at Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia Ararat Gomtsyan, Ph.D., Senior Analyst, Armen Safaryan, Ph.D., Senior Analyst Tamara Grigoryan, MBA, Senior Analyst at Center for Education, Policy Research and Economic Analysis ALTERNATIVE, Armenia 4 Guillermo Tolosa, IMF Resident Representative to Armenia International Monetary Fund, Headquartered -

Facilities Management Execution 2008 Will the Highest-Level Decision Makers and Policy Makers 1

Facilities Management BOOK AND PAY BEFORE 29 NOVEMBER 2007 Execution 2008 AND SAVE UP TO International Conference: 18-19 February 2008 US$700! Interactive Masterclass and Workshops: 17 and 20 February 2008 Venue: Shangri-La Hotel, Dubai, UAE Drive customer-centric facilities management able to exceed demanding expectations with practical execution and Middle East focused techniques Damac Properties Sorouh Real Estate Limitless Sama Dubai Emaar Properties Aldar Properties Vice President, Executive Director, Facilities Manager, Properties Manager, Senior Director Asset Head of Aldar Facility Management, Asset Management, Global Corporate North Africa Management, UAE Facility Businesses, UAE UAE Real Estate, UAE Sami Sulaiman Mick Dalton UAE Sanjay Batiya Anthony Abu Hamad Dan Davies Graham Yates Emirates Palace Grand Hyatt Dubai United Development Al Madar Group Memon Investments Al Mazaya Holding Hotel Property Manager, Director, Operations, Real Estate Manager, Managing Director, Company Chief Engineer, UAE UAE Qatar Qatar UAE Corporate Facilities Kankanam Philip Barnett David Cannon Kenneth Longmuir Ahmed Shakhani Engineer, Kuwait Dharmadasa Joseph Abunasif And Many More... Including two interactive workshops and a Masterclass that you can’t afford to miss: United Development: Mega FM: Facility Management Catered to Demanding Mega-Project Environments Emaar Properties: Drive Customer Retention And Attractiveness With Customer-Centric Facilities Management Sama Dubai: Remote Success: How You Can Remotely Manage Facilities Management To