Exhibitions in Postwar Rotterdam and Hamburg, 1946-1973

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aanvraagformulier Subsidie Dit Formulier Dient Volledig Ingevuld Te Worden Geüpload Bij Uw Aanvraag

Over dit formulier Aanvraagformulier subsidie Dit formulier dient volledig ingevuld te worden geüpload bij uw aanvraag. Brede regeling combinatiefuncties Rotterdam - Cultuur Privacy De gemeente gaat zorgvuldig om met uw gegevens. Meer leest u hierover op Rotterdam.nl/privacy. Contact Voor meer informatie: Anne-Rienke Hendrikse [email protected] Voordat u dit formulier gaat invullen, wordt u vriendelijk verzocht de Brede regeling combinatiefuncties Rotterdam – cultuur zorgvuldig te lezen. Heeft u te weinig ruimte om uw plan te beschrijven? dan kunt u dit als extra bijlage uploaden tijdens het indienen van uw aanvraag. 1. Gegevens aanvrager Naam organisatie Contactpersoon Adres Postcode (1234AB) Plaats Telefoonnummer (10 cijfers) Mobiel telefoonnummer (10 cijfers) E-mailadres ([email protected]) Website (www.voorbeeld.nl) IBAN-nummer Graag de juiste tenaamstelling Ten name van van uw IBAN-nummer gebruiken 129 MO 08 19 blad 1/10 2. Subsidiegegevens aanvrager Bedragen invullen in euro’s Gemeentelijke subsidie in het kader van het Cultuurplan 2021-2024 per jaar Structurele subsidie van de rijksoverheid (OCW, NFPK en/of het Fonds voor Cultuurparticipatie) in het kader van het Cultuurplan 2021-2024 per jaar 3. Gegevens school Naam school Contactpersoon Adres Postcode (1234AB) Plaats Telefoonnummer (10 cijfers) Fax (10 cijfers) Rechtsvorm Stichting Vereniging Overheid Anders, namelijk BRIN-nummer 4. Overige gegevens school a. Heeft de school een subsidieaanvraag gedaan bij de gemeente Rotterdam in het kader van de Subsidieregeling Rotterdams Onderwijsbeleid 2021-2022, voor Dagprogrammering in de Childrens Zone? Ja Nee b. In welke wijk is de school gelegen? Vul de bijlage in achteraan dit formulier. 5. Gegevens samenwerking a. Wie treedt formeel op als werkgever? b. -

Painting Amongst the Irises

La Fête Nationale A Bastille Day and Summer Gardens Duet General information This holiday is hosted by Louis Jansen van Vuuren, Hardy Olivier, and DeVerra Auret at the renowned Château de La Creuzette in the Limousin Region of France. (www.lacreuzette.com.) Keith Kirsten will be your knowledgeable guide accompanying the group as we explore the marvelous gardens and other special places of interest on the program. It is the week of Bastille celebrations and the glorious Summer gardens are in full bloom. Experience a magnificent overview of French garden styles with Keith Kirsten, guru of gardening and world-renowned horticulturist. From the spectacular formal gardens of Vaux-le-Vicomte just outside Paris to the world-renowned garden festival at Chaumont-sur-Loire. At La Creuzette we celebrate Bastille Day with a seductive dinner feast in the shimmering park, and we enjoy a special music concert before the fireworks and champagne corks start to pop. When: 10th till the 15th July 2019 Costs: €3 500 per person sharing and this includes: - Collection from Charles de Gaulle airport and road transfer via Giverny and the Loire region - One night’s stay in Giverny in twin rooms - One night’s stay in a Hotel in the Loire in twin rooms - Road transfer to La Creuzette - Luxurious accommodation at La Creuzette for the remaining 3 nights - Full board accommodation (i.e. all meals with drinks, also at restaurants we visit) - All excursions including entrance fees and gratuities - All music concerts and entertainment - Transfer to Bourges and train back to Paris at the end of the stay at La Creuzette. -

From 25Th April to 21St October © Corbis

From 25th April to 21st October www.domaine-chaumont.fr © Corbis. Le Reve (The Dream) Henri Rousseau. 1910. Oil on canvas, 298.5 x 204.5 cm (117.5 x 80.5 in). Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York, USA. York, New York, 298.5 x 204.5 cm (117.5 80.5 in). Museum of Modern Art, New 1910. Oil on canvas, Henri Rousseau. (The Dream) © Corbis. Le Reve Tel: +33 (0) 254 209 922 Domaine de Chaumont-sur-Loire Contents I. Introduction Page 3 II. A new 10-hectare extension to the grounds, landscaped by Pages 5 to 8 Louis Benech 1. The Grounds and the Prés du Goualoup 2. Biography: Louis Benech 3. Creation of a new permanent garden by Che Bing Chiu III. 2012 edition: Gardens of delight, gardens of delirium Pages 9 to 12 1. Theme 2. 1992-2012: 20 years of Festival IV. “Cartes Vertes” Pages 13 to 26 Jean-Philippe Poirée-Ville Shu Wang Nicolas Degennes Pablo Reinoso V. Alain Passard, President of the Jury for 2012 Pages 27 and 28 Alain Passard Composition of the 2012 Jury VI. The Festival’s gardens Pages 29 to 54 VII. The Arts and Nature Centre Pages 55 to 60 1. A multiple mission 2. An ambitious cultural project 3. The Grounds and the Domaine transformed 4. A continuing ecological concern 5. The Domaine’s key players 6. 2012 Cultural programmin VIII.Partners Pages 61 to 66 VI. Practical information Pages 67 and 68 VII. Visuals available to the press Pages 69 1 Domaine de Chaumont-sur-Loire For its 21st edition, the International Garden Festival has invited designers from all over the world to come up with the most amazing projects imaginable. -

Vermont History Expo Photographs and News

Vermont History Expo Photograph & News Media Collection, 2000-2012 FB-79 Introduction This collection contains selected newspaper and magazine articles, professional and amateur photographs, and slides of the Vermont History Expo during the years 2000 through 2012. It is housed in two document storage boxes and three archival storage boxes (3.25 linear feet). The core of the collection was transferred to the VHS Library by Sandra Levesque, Expo Coordinator working under contract to the VHS, in 2007. The remainder of the materials have been added from VHS office files. Organizational Sketch The Vermont Historical Society began hosting the Vermont History Expo at the Tunbridge Fairgrounds in Tunbridge, Vermont, for one weekend each June beginning in 2000. The event featured displays by participating local historical societies, museums, historical organizations, period crafters, demonstrators, and re-enactors. In addition there were historic presentations and speakers, musicians, heirloom animal displays and presentations, an authors’ tent, parade, and country auction. Thousands attended the weekend-long event which was held annually until 2008; the event resumed as a biannual event in 2010. The event had its genesis in the Heritage Weekend sponsored by the Cabot Creamery and the Vermont Historical Society in 1999. This event, an open house of historical societies in Washington and Orange Counties for one weekend in June, grew into the Vermont History Expo the following year. Sandra Levesque was the coordinator hired by the VHS to run the event between 1999 and 2006. The Expo event was preceded by a series of workshops for local historical societies on how to create effective displays. -

Les Expositions Universelles Et Internationales Comme Des Méga-Événements Une Incarnation Éphémère D’Un Fait Social Total ?

Horizontes Antropológicos 40 | 2013 Megaeventos Les expositions universelles et internationales comme des méga-événements une incarnation éphémère d’un fait social total ? Patrice Ballester Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/horizontes/247 ISSN : 1806-9983 Éditeur Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) Édition imprimée Date de publication : 18 septembre 2013 Pagination : 253-281 ISSN : 0104-7183 Référence électronique Patrice Ballester, « Les expositions universelles et internationales comme des méga-événements », Horizontes Antropológicos [En ligne], 40 | 2013, mis en ligne le 28 octobre 2013, consulté le 21 septembre 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/horizontes/247 © PPGAS Les expositions universelles et internationales comme des méga-événements 253 LES EXPOSITIONS UNIVERSELLES ET INTERNATIONALES COMME DES MÉGA-ÉVÉNEMENTS: UNE INCARNATION ÉPHÉMÈRE D’UN FAIT SOCIAL TOTAL? Patrice Ballester Académie de Toulouse – France Résumé: Les métropoles mondiales diversifi ent leur politique urbaine en organisant des méga-événements permettant la création, promotion et valorisation de comple- xe de foire. Les Expositions découlent de cette logique au même titre que les Jeux olympiques de 2016 à Rio de Janeiro et les mondiaux de football de 2014 au Brésil. Quels sont les effets durables d’un événement éphémère? À partir de la notion de fait social total selon Marcel Mauss, associée à une enquête de terrain pour Saragosse 2008 Expo et d’une analyse du dossier de candidature de São Paulo 2020 Expo, ces méga-événements incarnent à la fois un message humaniste tronqué dans le fait de rassembler le monde entier à travers un tourisme de masse réducteur, mais aussi un moyen de communication et de diffusion d’une culture nationale et d’un savoir-faire technique à l’échelle mondiale. -

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

The Artist As Researcher by Janneke Wesseling

Barcode at rear See it Sayit TheArt ist as Researcher Janneke Wesseling (ed.) Antennae Valiz, Amsterdam With contributions by Jeroen Boomgaard Jeremiah Day Siebren de Haan Stephan Dillemuth Irene Fortuyn Gijs Frieling Hadley+Maxwell Henri Jacobs WJMKok AglaiaKonrad Frank Mandersloot Aemout Mik Ruchama Noorda Va nessa Ohlraun Graeme Sullivan Moniek To ebosch Lonnie van Brummelen Hilde Van Gelder Philippe Va n Snick Barbara Visser Janneke Wesseling KittyZijlm ans Italo Zuffi See it Again, Say it Again: The Artist as Researcher Jan n eke We sse1 ing (ed.) See it Again, Say it Again: .. .. l TheArdst as Researcher Introduction Janneke We sseling The Use and Abuse of .. ...... .. .. .. .. 17 Research fo r Art and Vic e Versa Jeremiah Day .Art Research . 23 Hilde Va n Gelder Visual Contribution ................. 41 Ae rnout Mik Absinthe and Floating Tables . 51 Frank Mandersloot The Chimera ofMedtod ...... ........ ... 57 Jero en Boomgaard Reform and Education .. ...... ...... .. 73 Ruchama Noorda TheArtist as Researcher . 79 New Roles for New Realities Graeme Sullivan Visual Contribution .. .. .... .. .... .. 103 Ag laia Ko nrad Some Thoughts about Artistic . 117 Research Lonnie van Brummelen & Siebren de Haan Surtace Research . 123 Henri Jacobs TheArtist's To olbox .......... .......... 169 Irene Fortuyn Knight's Move . 175 The Idiosyncrasies of Artistic Research Ki tty Z ij 1 m a n s In Leaving the Shelter ................. 193 It alo Zu ffi Letterto Janneke Wesse6ng .......... 199 Va nessa Ohlraun Painting in Times of Research ..... 205 G ij s F r i e 1 ing Visual Contribution ........ .... ...... 211 Philippe Va n Snick TheAcademy and ........................... 221 the Corporate Pub&c Stephan Dillemuth Fleeting Profundity . 243 Mon iek To e bosch And, And , And So On . -

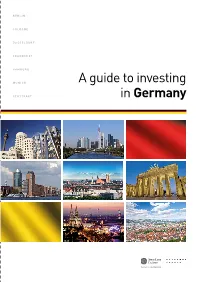

A Guide to Investing in Germany Introduction | 3

BERLIN COLOGNE DUSSELDORF FRANKFURT HAMBURG MUNICH A guide to investing STUTTGART in Germany ísafördur Saudharkrokur Akureyri Borgarnes Keflavik Reykjavik Selfoss ICELAND Egilsstadir A guide to investing in Germany Introduction | 3 BERLIN FINLAND ME TI HT NORWAY IG HELSINKI FL COLOGNE R 2H SWEDEN TALLINN OSLO INTRODUCTION ESTONIA STOCKHOLM IME T T GH LI DUSSELDORF F IN 0M 3 RIGA INVESTING IN GERMANY R 1H LATVIA E FRANKFURT EDINBURGH IM T T LITHUANIA GH DENMARK LI F R COPENHAGEN VILNIUS BELFAST 1H MINSK IRELAND HAMBURG DUBLIN BELARUS IME HT T LIG F IN HAMBURG M 0 UNITED KINGDOM 3 WARSAW Germany is one of the largest Investment Markets in Europe, with an average commercial AMSTERDAM BERLIN KIEV MUNICH NETHERLANDS POLAND transaction volume of more than €25 bn (2007-2012). It is a safe haven for global capital and LONDON BRUSSELS DÜSSELDORF COLOGNE UKRAINE offers investors a stable financial, political and legal environment that is highly attractive to both BELGIUM PRAGUE STUTTGART FRANKFURT CZECH REPUBLIC domestic and international groups. LUXEMBOURG PARIS SLOVAKIA STUTTGART BRATISLAVA VIENNA MUNICH BUDAPEST This brochure provides an introduction to investing in German real estate. Jones Lang LaSalle FRANCE AUSTRIA HUNGARY BERN ROMANIA has 40 years experience in Germany and today has ten offices covering all of the major German SWITZERLAND SLOVENIA markets. Our full-service real estate offering is unrivalled in Germany and we look forward to LJUBLJANA CROATIA BUCHAREST ZAGREB BELGRADE sharing our in-depth market knowledge with you. BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA SERBIA SARAJEVO BULGARIA ITALY SOFIA PRESTINA KOSOVO Timo Tschammler MSc FRICS SKOPJE HAMBURG MACEDONIA International Director ROME TIRANA MADRID ALBANIA Management Board Germany PORTUGAL Lisboa (Lisbon) SPAIN GREECE Office and Industrial, Jones Lang LaSalle Setúbal ATHENS BERLIN Germany enjoys a thriving, robust and mature real estate market which is one of the DÜSSELDORF cornerstones of the German economy. -

Rezension Im Erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC 2016

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Christoph Oliver Mayer Rezension im erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC 2016 https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2016.1.4446 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Rezension / review Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Mayer, Christoph Oliver: Rezension im erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC. In: MEDIENwissenschaft: Rezensionen | Reviews, Jg. 33 (2016), Nr. 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2016.1.4446. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung 3.0/ Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Attribution 3.0/ License. For more information see: Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Hörfunk und Fernsehen 99 Rezension im erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC Christine Ehardt, Georg Vogt, Florian Wagner (Hg.): Eurovision Song Contest: Eine kleine Geschichte zwischen Körper, Geschlecht und Nation Wien: Zaglossus 2015, 344 S., ISBN 9783902902320, EUR 19,95 Der Sieg von Conchita Wurst beim Triebel 2011; Goldstein/Taylor 2013) Eurovision Song Contest (ESC) 2014 sowie von einzelnen Wissenschaft- und die sich daran anschließenden ler_innen unterschiedlicher Disziplinen europaweiten Diskussionen um Tole- (z.B. Sieg 2013; Mayer 2015) angesto- ranz und Gleichberechtigung haben ßen wurden. eine ganze Palette von Publikationen Gemeinsam ist all den neueren über den bedeutendsten Populärmusik- Ansätzen ein gesteigertes Interesse für Wettbewerb hervorgerufen (z.B. Wol- Körperinszenierungen, Geschlech- ther/Lackner 2014; Lackner/Rau 2015; terrollen und Nationsbildung, denen Vogel et al. 2015; Kennedy O’Connor sich auch der als „kleine Geschichte“ 2015; Vignoles/O’Brien 2015). Nur untertitelte Sammelband der Wie- wenige wissenschaftliche Monografien ner Medienwissenschaftler_innen (z.B. -

Floriade , Verleden, Heden En Toekomst. Een Analyse Van Het Grootste Evenement Van Nederland

Floriade , verleden, heden en toekomst. Een analyse van het grootste evenement van Nederland 5-10-2015 International Destination Strategies Floriade , verleden, heden en toekomst. Inleiding Pagina 2 1. Floriade 1960 Rotterdam 3 2. Floriade 1972 Amsterdam 3-4 3. Floriade 1982 Amsterdam 5-6 4. Floriade 1992 Zoetermeer 7-9 5. Floriade 2002 Hoofddorp 10-13 6. Floriade 2012 Venlo 14-17 7. De bouw kosten van het tentoonstelling platform voor een Floriade 18-20 8. De Floriade en de begrippen “omzet, verlies en winst” 21-23 9. De oorzaken van dalende bezoekersaantallen van Floriade’s sinds 1992 24-31 10. De economische motivatie om een Floriade te organiseren 32-34 11. Financiële en organisatorische evaluaties van Floriades 35-37 12. De NTR 38-40 13. De kandidaten Floriade 2022 41 14. De politieke motivatie om een Floriade te organiseren 42 15. De Floriade 2022 Almere 43-49 16. De toekomst van de Floriade 50 Slotopmerkingen 51 Uitgave 4, Oktober 2015 Pagina 1 Floriade , verleden, heden en toekomst. Inleiding De Floriade is het grootste evenement met betalende bezoekers van Nederland en tevens de enige door de BIE (Bureau International des Exposition, Paris) erkende wereldtentoonstelling, welke elke 10 jaar in ons land plaats vindt. De afgelopen 34 jaar is ondergetekende in diverse functies betrokken geweest bij de Floriades 1982, 1992, 2002 en 2012. Mede op basis van deze ervaring is dit document opgesteld. Het doel van het document is een beter inzicht te geven in de problematieken welke spelen met betrekking tot de organisatie van een Floriade en hoe deze worden veroorzaakt. -

The Hamburg Rathaus Seat of the Hamburg State Parliament and the Hamburg State Administration

Hun bixêr hatin Mirë se erdhët Te aven Baxtale Welcome Bienvenue Willkommen THE HAMBURG RATHAUS SEAT OF THE HAMBURG STATE PARLIAMENT AND THE HAMBURG STATE ADMINISTRATION Kalender Englisch Umschlag U1-U4.indd 1 06.06.17 20:56 The Hamburg Rathaus Kalender Englisch Umschlag U1-U4.indd 2 06.06.17 20:57 The Hamburg Rathaus Seat of the state parliament and state administration Welcome to Hamburg! We hope that you will Hygieia and the dragon symbolize the conque- state parliament and the Hamburg state ad- settle in well and that Hamburg will become ring of the Hamburg cholera epidemic of 1892. minstration. your second home. With this brochure, we’d In Hamburg, the state parliament is called the like to introduce you to the Hamburg Rathaus, Bürgerschaft and the state administration is the city hall. It is the seat of Hamburg’s state called the Senat. parliament and administration. Perhaps it It is at the Rathaus where issues important is comparable to similar buildings in your to you are debated and resolutions made – countries, in which the state administration housing and health issues, education issues, or state parliament have their seats. and economic issues, for example. The Rathaus is in the middle of the city, and Please take the time to accompany us through was built more than 100 years ago, between the Hamburg Rathaus on the following pages, 1884 and 1897. With its richly decorated and learn about the work and the responsibili- commons.wikimedia.org/Brüning (gr.); Rademacher Jens Photos: façade, its width of 111 meters, its 112-meter ties of the Senat and the Bürgerschaft. -

Floriade. Verleden, Heden En Toekomst. Een Casestudie Van Een Nederlandse Wereld Tuinbouw Tentoonstelling

Floriade. Verleden, heden en toekomst. Een casestudie van een Nederlandse Wereld Tuinbouw Tentoonstelling. 1-6-2016 FLORIADE. VERLEDEN, HEDEN EN TOEKOMST. INHOUD 1. Inleiding ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Samenvatting. ................................................................................................................................................ 4 3. De Internationale Bloemententoonstellingen Flora. .................................................................................... 12 4. De Floriade 1960. ......................................................................................................................................... 13 5. Floriade 1972 Amsterdam ............................................................................................................................ 14 6. Floriade 1982 Amsterdam ............................................................................................................................ 16 7. Floriade 1992 Zoetermeer ............................................................................................................................ 19 8. “Lessons learned” van Floriade 1992 ........................................................................................................... 24 9. Floriade 2002 Hoofddorp ............................................................................................................................