The Making of John Walker Lindh -- Printout -- TIME

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Islamic Law Christie S

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 2008 Lifting the Veil: Women and Islamic Law Christie S. Warren William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Repository Citation Warren, Christie S., "Lifting the Veil: Women and Islamic Law" (2008). Faculty Publications. 99. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/99 Copyright c 2008 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs LIFTING THE VEIL: WOMEN AND ISLAMIC LAW CHRISTIES. WARREN * "Treat your women well and be kind to them for they are your partners and committed helpers." From the Farewell Address of the Holy Prophet Muhammad1 I. INTRODUCTION By the end of February 632 and at the age of sixty-three, the Prophet Muhammad believed that his days on earth were coming to an end.2 He announced to his followers that he would lead the hajj, the annual pilgrimage to Mecca, himself that year.3 On March 3, the Prophet delivered his farewell sermon near Mount Arafat.4 Among the limited number of topics he chose to include in his last public speech, he encouraged his followers to deal justly with one another and treat women well. 5 In the modem era, the rights of women under Islamic law have come under heightened scrutiny. Some commentators find the Prophet's farewell speech to be inconsistent with the way women are treated in some areas of the Muslim world. In Saudi Arabia, for example, women may neither drive nor vote. -

Black-Thursday.Pdf

Published on Books on Islam and Muslims | Al-Islam.org (https://www.al-islam.org) Home > Black Thursday Black Thursday رزﻳﺔ ﻳﻮم اﻟﺨﻤﻴﺲ English Translation of Raziyyat Yawm al-Khamees Author(s): Muhammad al-Tijani al-Samawi [3] Publisher(s): Ansariyan Publications - Qum [4] The text authored by Muhammad Al Tijani Al Samawi presents an english translation of the famous event of Raziyyat Yawm al-Khamees, known as Black Thursday which took place in the last days before the Holy Prophet's demise. It concerns an incident during the Prophet's illness when he asked for writing materials to dictate a will, but the people present around him said that he was talking nonsense. This event is a point of controversy between the two largest sects of Islam. This book presents the reality of what happened and who was the person involved who had the audacity to cast such aspersion on the Messenger of Allah (S). Translator(s): Sayyid Maqsood Athar [5] Category: Sunni & Shi’a [6] Early Islamic History [7] Prophet Muhammad [8] Miscellaneous information: Editor: Sayyid Athar Husain S. H. Rizvi First Edition: 2009-1388-1430 ISBN: 978-964-219-089-8 Featured Category: Debates & discussions [9] Translator’s Foreword In the Name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful. Praise be to Allah, the Lord of the worlds and benedictions be upon Prophet Muhammad and his Purified Progeny. The Important role that translation plays in propagation of religion is known to all. Since most Islamic texts are in Arabic or Persian, it is only through translating them into English can we make them popular among the literate Muslim youth of today. -

Resources for the Study of Islamic Architecture Historical Section

RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION Prepared by: Sabri Jarrar András Riedlmayer Jeffrey B. Spurr © 1994 AGA KHAN PROGRAM FOR ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION BIBLIOGRAPHIC COMPONENT Historical Section, Bibliographic Component Reference Books BASIC REFERENCE TOOLS FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE This list covers bibliographies, periodical indexes and other basic research tools; also included is a selection of monographs and surveys of architecture, with an emphasis on recent and well-illustrated works published after 1980. For an annotated guide to the most important such works published prior to that date, see Terry Allen, Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography. Cambridge, Mass., 1979 (available in photocopy from the Aga Khan Program at Harvard). For more comprehensive listings, see Creswell's Bibliography and its supplements, as well as the following subject bibliographies. GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHIES AND PERIODICAL INDEXES Creswell, K. A. C. A Bibliography of the Architecture, Arts, and Crafts of Islam to 1st Jan. 1960 Cairo, 1961; reprt. 1978. /the largest and most comprehensive compilation of books and articles on all aspects of Islamic art and architecture (except numismatics- for titles on Islamic coins and medals see: L.A. Mayer, Bibliography of Moslem Numismatics and the periodical Numismatic Literature). Intelligently organized; incl. detailed annotations, e.g. listing buildings and objects illustrated in each of the works cited. Supplements: [1st]: 1961-1972 (Cairo, 1973); [2nd]: 1972-1980, with omissions from previous years (Cairo, 1984)./ Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography, ed. Terry Allen. Cambridge, Mass., 1979. /a selective and intelligently organized general overview of the literature to that date, with detailed and often critical annotations./ Index Islamicus 1665-1905, ed. -

Abbreviations and Acronyms

PART II] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JULY 23, 2019 1505(1) ISLAMABAD, TUESDAY, JULY 23, 2019 PART II Statutory Notifications (S. R. O.) GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN REVENUE DIVISION (Federal Board of Revenue) NOTIFICATIONS Islamabad, the 23rd July, 2019 (INCOME TAX) S.R.O. 829(I)/2019.—In exercise of the powers conferred by sub- section (4) of section 68 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 (XLIX of 2001) and in supersession of its Notification No. S.R.O. 111(I)/2019 dated the lst February, 2019, the Federal Board of Revenue is pleased to notify the value of immoveable properties in columns (3) and (4) of the Table below in respect of areas of Abbottabad classified in column (2) thereof. (2) This notification shall come into force with effect from 24th July, 2019. 1505 (1—211) Price: Rs. 320.00 [1143(2019)/Ex.Gaz.] 1505(2) THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JULY 23, 2019 [PART II ABBOTTABAD Value of Commercial Value of Residential S.No. Areas property per marla property per marla (in Rs.) (in Rs.) (1) (2) (3) (4) 1 Main Bazar, Sadar Bazar, Jinnah Road, Masjid Bazar, 2,580,600 910,800 Sarafa Bazar Gardawara Gali Kutchery Road, Shop and Market. 2 Abbottabad Bazar 2,580,600 759,000 3 Iqbal Road 1,214,400 531,300 4 Mansehra Road 1,973,400 531,300 5 Jinnah Abad 2,277,000 1,062,600 6 Habibullah Colony - 1,062,600 7 Kaghan Colony 759,000 455,400 S.R.O. 830(I)/2019.—In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (4) of section 68 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 (XLIX of 2001) and in supersession of its Notification No. -

Islam, Ritual and the Ethical Life

ISLAM, RITUAL AND THE ETHICAL LIFE DAWAT IN THE TABLIGHI JAMAAT IN PAKISTAN Arsalan Khalid Khan Charlottesville, Virginia M.A. Anthropology, University of Virginia 2011 B.A. International Relations, Beloit College 2005 A Dissertation Presented to The Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology December, 2014 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Islam and the Colonial Configuration of Religion 46 3. Ritual Ideology: Dawat, Personhood, Purity 74 4. Piety as Ethical Relatedness 110 5. From Precarious to Certain Faith: The Making of a Spiritual Home 156 6. Dawat and Transcendence in an Islamic Nation 195 7. Conclusion: Dawat as Islamic Modernity 240 1 Acknowledgements The research for this dissertation was funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation, The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia, and the Department of Anthropology at the University of Virginia. The faculty in the Department of Anthropology at UVa provided me with a warm and nurturing space to develop as a scholar. I am most indebted to my dissertation chair and adviser, Richard Handler, for his unwavering support and encouragement without which I may never have been able to see this task to completion. I consider my work mostly a dialogue with what I have learned from him over these many years. I also want to extend my gratitude to the members of my committee. Dan Lefkowitz’s insights into performance helped me frame key aspects of my dissertation. Peter Metcalf consistently encouraged me to ground my theoretical arguments in ethnography, which I have tried to do. -

The Provenance of Arabic Loan-Words in a Phonological and Semantic Study. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosoph

1 The Provenance of Arabic Loan-words Hausa:in a Phonological and Semantic study. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the UNIVERSITY OF LONDON by Mohamed Helal Ahmed Sheref El-Shazly Volume One July 1987 /" 3ISL. \ Li/NDi V ProQuest Number: 10673184 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673184 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 VOOUMEONE 3 ABSTRACT This thesis consists of an Introduction, three Chapters, and an Appendix. The corpus was obtained from the published dictionaries of Hausa together with additional material I gathered during a research visit to Northern Nigeria. A thorough examination of Hausa dictionaries yielded a large number of words of Arabic origin. The authors had not recognized all of these, and it was in no way their purpose to indicate whether the loan was direct or indirect; the dictionaries do not always give the Arabic origin, and sometimes their indications are inaccurate. The whole of my corpus amounts to some 4000 words, which are presented as an appendix. -

Competing and Conflicting Power Dynamics in Waqfs in Kenya, 1900-2010

Competing and Conflicting Power Dynamics in Waqfs in Kenya, 1900-2010 Chembea, Suleiman Athuman Thesis Submitted to the Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS) in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Islamic Studies of the Bayreuth University, Germany Supervisor: Dr. Franz Kogelmann March 2017 i Dedication To my wife, friend, and the mother of my children, Nuria For your love and support ii Acknowledgement I am immensely indebted to all, both institutions and individuals, who contributed in various levels and ways towards the successful completion of this academic piece. Sincere thanks to the Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst (DAAD), Germany, and the National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation (NACOSTI) Kenya, for granting me the scholarship to undertake this study; the Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS), Bayreuth University, Germany, for accepting me as a Doctoral candidate and co-funding my fieldworks; the Teachers Service Commission (TSC) Kenya, for granting me study leave to concentrate on this project; and the Waqf Commission of Kenya (WCK) Mombasa, for the permission to use their facilities during fieldwork. My heartfelt compliments to my supervisor and academic father-figure, Dr. Franz Kogelmann, for the faith he entrusted in me by accepting me as his Doctoral candidate. Words would fail me to express my gratitude for his support in shaping this project since the first time we met in the Summer School on Religion and Order in Africa in 2010 here at Bayreuth. My sincere appreciation to my two mentors, Prof. Dr. Rüdiger Seesemann and Prof. -

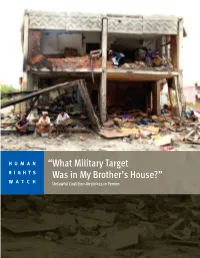

“What Military Target Was in My Brother's

H U M A N “What Military Target R I G H T S Was in My Brother’s House?” WATCH Unlawful Coalition Airstrikes in Yemen “What Military Target Was in My Brother’s House” Unlawful Coalition Airstrikes in Yemen Copyright © 2015 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-162431-33009 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org NOVEMBER 2015 978-162431-33009 “What Military Target Was in My Brother’s House” Unlawful Coalition Airstrikes in Yemen Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .......................................................................................................... -

(Mis)Adventures in the Horn of Africa

Foreword The United States will continue to lead an expansive international effort in pursuit of a two-pronged vision: 1) The defeat of violent extremism as a threat to our way of life as a free and open society; and 2) The creation of a global environment inhospitable to violent extremists and all who support them.1 — President Bush September 2006 In February 2006, the Combating Terrorism Center released Harmony and Disharmony: Exploiting al-Qa’ida’s Organizational Vulnerabilities. Its authors analyzed declassified internal al-Qa’ida documents captured during operations in support of the Global War on Terror and maintained on the Department of Defense’s Harmony Database. These declassified documents, which are corroborated by multiple open source materials, provide evidence that al-Qa’ida struggles with many of the same issues and challenges that all organizations in the private and public sectors confront. The Combating Terrorism Center recommended that effective strategies to defeat al-Qa’ida and likeminded groups should include measures that leverage and heighten their dysfunctional structure, competition, and behavior. In Al-Qa’ida’s (Mis)Adventures in the Horn of Africa, the Combating Terrorism Center’s team of area experts and terrorism scholars analyzed al-Qa’ida’s attempts to establish bases of operations and recruit followers in the Horn of Africa. According to a new set of recently declassified documents from the Harmony Database, al-Qa’ida operatives encountered significant problems as they ventured into the foreign lands of the Horn. The environment was far more inhospitable than they anticipated. The same conditions that make it difficult, or in many cases impossible, for state authorities to exert control in this region—poor infrastructure, scarce resources, competition with tribal and other local authority structures—were significant problems for al-Qa’ida as well. -

Muslim Principles of Marrying Al-Kitabiyyah and It Practice in Malawi

MUSLIM PRINCIPLES OF MARRYING AL-KITABIYYAH and its practice in Malawi by All Yusuf Andiseni DISSERTATION submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS in Islamic Studies in the FACULTY OF ARTS at the RAND AFRIKAANS UNIVERSITY April 1997 Supervisors: Prof ARI Doi Prof JFJ van Rensburg i Declaration I declare that Muslim Principles of Marrying Al- Kitabiyyah and its practice in Malawi is my own work and that all the sources which I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by appropriate references. Ali Yu-'f Andiseni ii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my mother whose life style was an, inspiration to me since I was young. She instilled the value of Education and the illumination of Islam within me. This produced the energy and strength within myself to undertake this Research. Unfortunately she did not live long enough to see the fruits of her efforts. May Allah grant her an elevated stage in Paradise. iii Acknowledgements All praise due to Allah who enabled me to pursue my post graduate studies and bestowed upon me the ability to complete this thesis. Firstly, I am deeply indebted to Professor lAbd al-Rabman I. Doi, my supervisor and constant guide for sacrificing his time in guiding me with invaluable suggestions and advices while preparing this thesis. Had I riot constantly worked in the shadow of his guidance and close direction, this thesis would not have reached the desired level of quality. I am equally thankful to Professor JFJ van Rensburg, my co- supervisor, who provided me with invaluable guidance on how to collect the source-material for my thesis, which books were the best to be consulted, and where they were to be located. -

Ottoman Mosques in Sana'a, Yemen Archeological and Architectural Study

JOURNAL OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE P-ISSN: 2086-2636 E-ISSN: 2356-4644 Journal Home Page: http://ejournal.uin-malang.ac.id/index.php/JIA O TTOMAN MOSQUES IN SANA'A, YEMEN ARCHEOLOG ICAL AND A RCHITECTURAL STUDY |Received June 27th 2016 | Accepted March 6th 2017| Available online June 15th 2017| | DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.18860/jia.v4i3.3533 | Mohamed Ahmed Abd El Rahman Enab A BSTRAC T Department of Islamic archeology Faculty of archeology, Fayoum University, The Ottoman presence in Yemen is divided into two periods, first period from Fayoum, Egypt 945 AH until 1045 AH, and then the second from 1289 AH until 1336 AH, [email protected] Ottomans interested during their presence in Yemen to establish different types of charitable buildings especially, religious buildings, which include mosques, madrassas, and shrines. The aim of interest of Ottomans governors to make significant civilized and architectural renaissance in Yemen, especially Sana'a, with emphasis on establishment mosques to get closer to God and to gain sympathy and love of the people of Yemen. Most of these mosques do the role of the madrassas as documents indicate like mosque of Özdemir, Al-Muradiyya and Al-Bakiriyya therefore, Ottomans are Hanifite Sunni and want by these mosques to facing shite and spread Sunni. In this paper researcher will discuss styles of Ottoman mosques in Sana'a. There are eight mosques, seven dates to the first period of Ottomans in Yemen and only one date to the second period of Ottomans in Yemen. KEYWO RDS: Ottomans, Al-Bakiriyya, Özdemir, Sinan -

The Case of Saudi Arabia

About the Author: NORMAN CIGAR retired as Director of Regional Studies and the Minerva Research Chair from the U.S. Marine Corps University, where he previously also taught military theory, operational case studies, insurgency warfare, strategy and policy, and Middle East regional studies at the School of Advanced Warfighting and at the Command and Staff College. In an earlier assignment, he was the senior civilian political- military staff officer in the Pentagon responsible for the Middle East in the Office of the Army’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence, and supported the Secretary of the Army, the Chief of Staff of the Army, and Congress with intelligence. He also represented the Army on national-level intelligence issues in the interagency intelligence community. In another assignment, he was Director of the Army’s Psychological Operations Strategic Studies Detachment responsible for the Middle East and Africa at Fort Bragg. He has been a consultant on multiple occasions at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia at the Hague and was a Visiting Fellow at the Institute for Conflict Analysis & Resolution, George Mason University. He has written widely on issues in the Middle East and the Balkans. Dr. Cigar holds a DPhil from Oxford (St Antony’s College) in Middle East History and Arabic; an M.I.A. from the School of International and Public Affairs and a Certificate from the Middle East Institute, Columbia University; and an M.S. in Strategic Intelligence from the Defense Intelligence College. He has studied and traveled widely in the Middle East. About the Series: The NCHR Occasional Paper Series is an open publication channel reflecting the work carried out by the Centre as a whole on a range of human rights topics.